Cleaner fish

Cleaner fish are fish that show a specialist feeding strategy[1] by providing a service to other species, referred to as clients,[2] by removing dead skin, ectoparasites, and infected tissue from the surface or gill chambers.[2] This example of cleaning symbiosis represents mutualism and cooperation behaviour,[3] an ecological interaction that benefits both parties involved. However, the cleaner fish may consume mucus or tissue, thus creating a form of parasitism[4] called cheating. The client animals are typically fish of a different species,[3] but can also be aquatic reptiles (sea turtles and marine iguana), mammals (manatees and whales), or octopuses.[5][6][7] A wide variety of fish including wrasse, cichlids, catfish, pipefish, lumpsuckers, and gobies display cleaning behaviors across the globe in fresh, brackish, and marine waters but specifically concentrated in the tropics due to high parasite density.[2] Similar behavior is found in other groups of animals, such as cleaner shrimps.

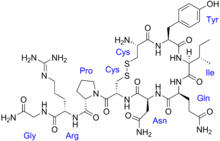

There are two types of cleaner fish, obligate full time cleaners and facultative part time cleaners[1] where different strategies occur based on resources and local abundance of fish.[1] Cleaning behaviour takes place in pelagic waters as well as designated locations called cleaner stations.[8] Cleaner fish interaction durations and memories of reoccurring clients are influenced by the neuroendocrine system of the fish, involving hormones arginine vasotocin, Isotocin and serotonin.[3]

Conspicuous coloration is a method used by some cleaner fish, where they often display a brilliant blue stripe that spans the length of the body.[9] Other species of fish, called mimics, imitate the behavior and phenotype of cleaner fish to gain access to client fish tissue.

The specialized feeding behaviour of cleaner fish has become a valuable resource in salmon aquaculture in Atlantic Canada, Scotland, Iceland and Norway[10] for prevention of sea lice outbreaks[2] which benefits the economy and environment by minimizing the use of chemical delousers. Specifically cultured for this job are lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus) and ballan wrasse (Labrus bergeylta).[11] The most common parasites that cleaner fish feed on are gnathiidae and copepod species.[1]

Diversity and examples

Marine fishes

The following is a selection of few of the many marine cleaner species.

Commonly studied cleaner fish are the cleaner wrasse of the genus Labroides found on coral reefs in the Indian Ocean and Pacific Ocean.[12]

Neon gobies of the genera Gobiosoma and Elacatinus provide a cleaning service similar to the cleaner wrasse, though this time on reefs in the Western Atlantic, providing a good example of convergent evolution[13] of the cleaning behaviour.

Lumpfish are utilized as salmonid cleaner fish in aquaculture, but it is unknown if they display cleaning behaviour on salmon in the wild.[14]

A disruptively patterned white-spotted puffer being cleaned by a conspicuously coloured Hawaiian cleaner wrasse.

A disruptively patterned white-spotted puffer being cleaned by a conspicuously coloured Hawaiian cleaner wrasse. Lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus), a cleaner fish employed in salmon farming in Atlantic Canada, Scotland, Iceland and Norway[15]

Lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus), a cleaner fish employed in salmon farming in Atlantic Canada, Scotland, Iceland and Norway[15] A neon goby from the Western Atlantic.

A neon goby from the Western Atlantic.

Brackish water fish

Brackish water refers to aquatic environments that have a salinity in between salt and fresh water systems. Cleaning symbiosis has also been observed in these areas between two brackish water cichlids of the genus Etroplus from South Asia. The small species Etroplus maculatus is the cleaner fish, and the much larger Etroplus suratensis is the host that receives the cleaning service.[16]

Freshwater fish

Cleaning has been observed infrequently in fresh waters compared to marine waters. This is possibly related to fewer observers (such as divers) in freshwater compared to saltwater.[17] One of the few known examples of freshwater cleaning is juvenile striped Raphael catfish cleaning the piscivorous Hoplias cf. malabaricus. In public aquariums, Synaptolaemus headstanders have been seen cleaning larger fish.[18][19]

Mechanisms

Facultative cleaner fish

A facultative cleaner fish does not rely solely on specialized cleaning behaviour for nutritious food.[20] Facultative cleaners can be further divided by stationary vs. wandering facultative cleaners.[21] Facultative cleaners may display cleaning behaviour through their whole life history or solely as juveniles for additional nutrients during rapid growth.[21][20] Examples of facultative cleaners are commonly wrasse species such as the blue headed wrasse, noronha wrasse (Thalassoma noronhanum) and goldsinny wrasse (Ctenolabrus rupestris), sharp nose sea perch in Californian waters,[20] and the lumpfish (Cyclopterus lumpus).

Using the example of the blue wrasse from Caribbean waters, their alternative feeding strategy is described as being a generalist forager, meaning they eat a wide variety of smaller aquatic organisms based on availability.[21] When displaying cleaning behaviour, it has been noted that the blue wrasse inspects potential clients and only feeds on some, implying that the wrasse is seeking out a particular type of parasite as a diet supplement. It has also been quantified that the blue wrasse foraging behaviour does not change in proportion to cleaning opportunities, again suggesting that the cleaning behaviour in this facultative fish is for diet supplementation and not out of necessity.[21]

Obligate cleaner fish

An obligate cleaner fish relies solely on specialized cleaning behaviour for its food.[20] Therefore, obligate cleaners have a higher output of cleaning on a wider range of parasites in comparison to facultative fish. To maximize nutrient consumption, obligate cleaners utilize a higher proportion of cleaning stations.[21] Obligate cleaner fish may also be divided by stationary and wandering. These life history choice are made based on the amount of interspecific competition from other obligate cleaners in the area.[22] An example of an obligate cleaner is the shark nose goby (Elacatinus evelynae) in the Caribbean Reef, where it has been observed to perform up to 110 cleanings per day.[21]

Cleaner stations

Cleaning stations are a strategy used by some cleaner fish where clients congregate and perform specific movements to attract the attention of the cleaner fish. Cleaning stations are usually associated with unique topological features, such as those seen in coral reefs[21] and allow a space where cleaners have no risk of predation from larger predatory fishes, due to the mutual benefit from the cleaners' service.[23]

Interactions are begun by the client and ended by the cleaner, implying that the client is seeking out the service where the cleaner has control.[20]

Cheating

Cheating parasitism occurs when the cleaner eats mucus or healthy tissue from the client. This can be harmful to the client as mucus is essential to prevent UV damage, and open wounds can increase the risk of infection.[20] Cleaner fish maintain a balance between eating ectoparasites and mucus or tissue because of the respective nutritional benefits, sometimes despite the risk to the client.[24] For example, the Caribbean cleaning goby (Elacatinus evelynae) will eat scales and mucus from the host during times of ectoparasite scarcity to supplement its diet. The symbiosis relationship between client and host does not break down because the abundance of these parasites varies significantly seasonally and spatially, and the overall benefit to the larger fish outweighs any cheating on by the smaller cleaner.[25]

Memory

Cleaner fish (especially facultative cleaners) assess the value of possible clients when deciding whether to invest in a client or cheat and eat mucus or tissue.[21][26] Observations of cleaner and client interactions have found that cleaners may provide the client with tactile stimulation as a way to establish a relationship and gain the client's 'trust'. This interaction costs the cleaner as it is time not spent feeding.[26] This physical interaction demonstrates a cleaner fish's tradeoff. The cleaner minimizes feeding time to establish a memorable relationship with the client that also contributes to conflict management with a possibly predatory client.[26]

Neurobiology

The cleaner fish neuroendocrine system has been studied specifically in reference to arginine vasotocin (AVT) and Isotocin. These are fish-specific hormones that are analogous to human hormones involved in sociality.[27] In laboratory experiments, during conditions of low AVT, cleaners are more engaged in interspecific interactions. High AVT conditions tend to show high client interactions but more instances of cheating. This implies that AVT expression acts as a switch for cleaner fish feeding behaviour, showing less client interactions (but more honest cleaning) or increased client interactions (with less honest cleaning).[27] It has also been observed that obligate cleaners have higher overall brain activity, and specifically in the cerebellum, likely related to the movements involved in cleaning.[27]

Serotonin has also been noted to influence cleaning behaviour. High serotonin increases motivation to interact with clients, and a lack of serotonin decreases client interaction and slows learning.[27]

Mimicry

.jpg)

Mimic species have evolved body forms, patterns, and colors which imitate other species to gain a competitive advantage.[28] One of the most studied examples of mimicry on coral reefs is the relationship between the aggressive mimic Plagiotremus rhinorhynchos (the bluestriped fangblenny) and the cleaner wrasse model Labroides dimidiatus. By appearing like L. dimidiatus, P. rhinorhynchos is able to approach and then feed on the tissue and scales of client fish while posing as a cleaner.[29][30]

The presence of the cleaner mimic, P. rhinorhynchos, reduces the foraging success of the cleaner model L. dimidiatus.[30] P. rhinorhynchos feeds by eating the tissue and scales of client fish, making client fish much more cautious while at cleaning stations. More aggressive mimics have a greater negative impact on the foraging rate and success of the cleaner fish.[30] When mimics appear in higher densities relative to cleaners, there is a significant decline in the success rate of the cleaner fish. The effects of the mimic/model ratio are susceptible to dilution, whereby an increase in client fish allows both the mimics and the models to have more access to clients, thus limiting the negative effects that mimics have on model foraging success.[31][32]

Similar species also include Plagiotremus tapeinosoma (the Mimic blenny), Aspidontus.

Implications

Salmonid aquaculture

Aquaculture is the farming of aquatic organisms, where salmon farming is growing in the North Atlantic.[33] Cleaner fish are used to eat parasitic sea lice from salmon to reduce outbreaks which cause disease in populations. The two most commonly used cleaner fish are the lumpfish, Cyclopterus lumpus, and the ballan wrasse Labrus bergeylta.[34] Lumpfish are distributed across the Atlantic ocean, ranging from Greenland to France, Hudson's Bay to New Jersey, and in high concentrations in the Bay of Fundy and St. Pierre Coast, near Newfoundland.[35] Ballan wrasse are distributed widely across the Northeast Atlantic Ocean.[36] The switch towards lumpfish has been preferred as wrasse are less active feeders during winter months.[37]

Methods

Cleaner fish are commercially cultured and introduced into salmonid sea cages. Salmon and lumpfish are able to coexist, where the lumpfish spend a certain amount of time foraging for supplemented food and only a portion of their time delousing salmon. With significant ratios of cleaner to client, the efforts are sufficient to minimize louse outbreaks.[37][34] Sea cages are designed with additional substrate for lumpfish to attach to during periods of inactivity to minimize stress levels in the cleaner fish and maximize delousing abilities.[37]

Challenges of using cleaner fish

North Atlantic Aquaculture facilities use facultative cleaner fish (Cyclopterus lumpus, and Labrus bergeylta) in order to control the nutrients they receive during culturing, before their use in aquaculture. One of the challenges that comes along with using facultative cleaners is that parasite removal from salmon must be maximized while also balancing additional nutrients from supplemented feed to ensure the health of the cleaner fish and the safety of the salmonid clients.[38] Another challenge that arises in management of cleaner fish behaviour is balancing the number of cleaners to the number of clients. With a low cleaner-to-client ratio, the risk of lice infestation increases. With a high cleaner-to-client ratio, competition among cleaners increases and there is a higher risk of cheating and consumption of salmonid mucus and flesh thereby increasing their risk of infection.[38][34]

Minimizing disease in commercial lumpfish stocks is critical for the continuation of their usage in aquaculture. Vaccine development for the lumpfish is a current area of research as lumpfish demand is increasing in the aquaculture industry.[37] In an effort to minimize disease in the cleaner fish, commercial lumpfish stocks are supplemented with wild individuals during the breeding season to minimize inbreeding depression. The lumpfish genome has not yet been fully sequenced so subtle details between populations are not yet appreciated.[37]

Another consideration in using cleaner fish in aquaculture is minimizing escapees from sea cages. If escaped cleaner fish spawn with natural populations in the environment it may decrease the wild fishes' natural survival abilities.[37]

Environment

Cleaner fish have taken over lice-reduction strategies, which were based upon chemical delousers in the past. This decreases the amount of effluent waste affecting the surrounding wild habitats in outdoor aquaculture.[34] Introducing cleaner fish into salmonid aquaculture cages has also been found to be less stressful on salmonids than medical intervention for sea lice outbreaks.[37]

Cleaner fish in the wild contribute to the overall health of aquatic communities by reducing morphological and physiological injuries by parasites to other species of fish. Maintenance of these populations of fish help the complex web of interactions remain stable.[39]

Economic

Sea lice outbreaks are detrimental to the survival of cultured salmonids and cause the majority of revenue loss in the aquaculture business. By employing the cleaner fish instead of medical intervention for sea louse management, aquaculture farmers save money.[37]

See also

- Doctor fish, fish that provide a cleaning service to humans

- Reciprocal altruism

- Social grooming, cleaning services offered between members of the same species

References

- Dunkley, Katie; Cable, Jo; Perkins, Sarah E. (2018-02-01). "The selective cleaning behaviour of juvenile blue-headed wrasse (Thalassoma bifasciatum) in the Caribbean". Behavioural Processes. 147: 5–12. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.12.005. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 29247694.

- Morado, Nadia; Mota, Paulo G.; Soares, Marta C. (2019). "The Rock Cook Wrasse Centrolabrus exoletus Aims to Clean". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00182. ISSN 2296-701X.

- Soares, Marta C. (2017). "The Neurobiology of Mutualistic Behavior: The Cleanerfish Swims into the Spotlight". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 11: 191. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00191. PMC 5651018. PMID 29089876.

- Gingins, Simon; Werminghausen, Johanna; Johnstone, Rufus A.; Grutter, Alexandra S.; Bshary, Redouan (2013-06-22). "Power and temptation cause shifts between exploitation and cooperation in a cleaner wrasse mutualism". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1761): 20130553. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0553. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3652443. PMID 23615288.

- Grutter, A. S. (2002). "Cleaning symbioses from the parasites' perspective". Parasitology. 124 (7): 65–81. doi:10.1017/S0031182002001488. ISSN 0031-1820. PMID 12396217.

- Sazima, Cristina; Grossman, Alice; Sazima, Ivan (2010-02-05). "Turtle cleaners: reef fishes foraging on epibionts of sea turtles in the tropical Southwestern Atlantic, with a summary of this association type". Neotropical Ichthyology. 8 (1): 187–192. doi:10.1590/S1679-62252010005000003. ISSN 1982-0224.

- "Manatee gets 'haircut' from gill fish". Daily Telegraph. 2010-02-26. ISSN 0307-1235. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Helfman, Gene S. (1997). The diversity of fishes. Collette, Bruce B., Facey, Douglas E. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0865422567. OCLC 36051279.

- Cheney, Karen L.; Grutter, Alexandra S.; Blomberg, Simon P.; Marshall, N. Justin (2009). "Blue and Yellow Signal Cleaning Behavior in Coral Reef Fishes". Current Biology. 19 (15): 1283–1287. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2009.06.028. PMID 19592250.

- "Cleaner fish – what do they do?". Lochduart. 2017-06-08. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- Brooker, Adam J; Papadopoulou, Athina; Gutierrez, Carolina; Rey, Sonia; Davie, Andrew; Migaud, Herve (2018-09-29). "Sustainable production and use of cleaner fish for the biological control of sea lice: recent advances and current challenges". Veterinary Record. 183 (12): 383. doi:10.1136/vr.104966. hdl:1893/27595. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 30061113.

- Helfman, Gene S. (1997). The diversity of fishes. Collette, Bruce B., Facey, Douglas E. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0865422567. OCLC 36051279.

- Fenner, Robert M. (1998). The conscientious marine aquarist : a commonsense handbook for successful saltwater hobbyists. Shelburne, Vt.: Microcosm. ISBN 1890087033. OCLC 38168280.

- Powell, Adam; Treasurer, Jim W.; Pooley, Craig L.; Keay, Alex J.; Lloyd, Richard; Imsland, Albert K.; Leaniz, Carlos Garcia de (2018). "Use of lumpfish for sea-lice control in salmon farming: challenges and opportunities". Reviews in Aquaculture. 10 (3): 683–702. doi:10.1111/raq.12194. ISSN 1753-5131.

- "Cleaner fish – what do they do?". Lochduart. 2017-06-08. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Wyman, Richard L.; Ward, Jack A. (1972-12-29). "A Cleaning Symbiosis between the Cichlid Fishes Etroplus maculatus and Etroplus suratensis. I. Description and Possible Evolution". Copeia. 1972 (4): 834. doi:10.2307/1442742. ISSN 0045-8511. JSTOR 1442742.

- Carvalho, L.N (2007). "Natural history of Amazon fishes". In Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems (ed.). Tropical Biology and Natural Resources Theme. 1. Oxford: Eolss Publishers. pp. 1–24.

- Planet, Den Blå; Fortlingsvej 1, Address: Jacob; Kastrup, Address: 2770; info@denblaaplanet.dk, Send email; Phone: +45 44 22 22 44 (2016-10-03). "Broadband red headstander". Den Blå Planet. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- "Broadband red headstander". National Aquarium Denmark. 2016-10-03. Retrieved 18 August 2018.

- Morado, Nadia; Mota, Paulo G.; Soares, Marta C. (2019). "The Rock Cook Wrasse Centrolabrus exoletus Aims to Clean". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00182. ISSN 2296-701X.

- Dunkley, Katie; Cable, Jo; Perkins, Sarah E. (2018-02-01). "The selective cleaning behaviour of juvenile blue-headed wrasse (Thalassoma bifasciatum) in the Caribbean". Behavioural Processes. 147: 5–12. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.12.005. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 29247694.

- Adam, T. C.; Horii, S. S. (2012). "Patterns of resource-use and competition for mutualistic partners between two species of obligate cleaner fish". Coral Reefs. 31 (4): 1149–1154. Bibcode:2012CorRe..31.1149A. doi:10.1007/s00338-012-0933-9.

- Helfman, Gene S. (1997). The diversity of fishes. Collette, Bruce B., Facey, Douglas E. Malden, Mass.: Blackwell Science. ISBN 0865422567. OCLC 36051279.

- Gingins, Simon; Werminghausen, Johanna; Johnstone, Rufus A.; Grutter, Alexandra S.; Bshary, Redouan (2013-06-22). "Power and temptation cause shifts between exploitation and cooperation in a cleaner wrasse mutualism". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 280 (1761): 20130553. doi:10.1098/rspb.2013.0553. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 3652443. PMID 23615288.

- Cheney, Karen L; Côté, Isabelle M (2005-05-16). "Mutualism or parasitism? The variable outcome of cleaning symbioses". Biology Letters. 1 (2): 162–165. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0288. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1626222. PMID 17148155.

- Soares, Marta C. (2017). "The Neurobiology of Mutualistic Behavior: The Cleanerfish Swims into the Spotlight". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 11: 191. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00191. PMC 5651018. PMID 29089876.

- Soares, Marta C. (2017). "The Neurobiology of Mutualistic Behavior: The Cleanerfish Swims into the Spotlight". Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience. 11: 191. doi:10.3389/fnbeh.2017.00191. PMC 5651018. PMID 29089876.

- Cheney, Karen L.; Grutter, Alexandra S.; Marshall, N. Justin (2008-01-22). "Facultative mimicry: cues for colour change and colour accuracy in a coral reef fish". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 275 (1631): 117–122. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0966. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2596177. PMID 17986437.

- Cheney, Karen L.; Grutter, Alexandra S.; Marshall, N. Justin (2008-01-22). "Facultative mimicry: cues for colour change and colour accuracy in a coral reef fish". Proceedings. Biological Sciences. 275 (1631): 117–122. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0966. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 2596177. PMID 17986437.

- Cheney, Karen L. (2012-02-23). "Cleaner wrasse mimics inflict higher costs on their models when they are more aggressive towards signal receivers". Biology Letters. 8 (1): 10–12. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2011.0687. PMC 3259977. PMID 21865244.

- Cheney, Karen L; Côté, Isabelle M (2007-09-07). "Aggressive mimics profit from a model–signal receiver mutualism". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 274 (1622): 2087–2091. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.0543. PMC 2706197. PMID 17591589.

- Cheney, Karen L; Côté, Isabelle M (2005-12-22). "Frequency-dependent success of aggressive mimics in a cleaning symbiosis". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 272 (1581): 2635–2639. doi:10.1098/rspb.2005.3256. ISSN 0962-8452. PMC 1559983. PMID 16321786.

- "Cleaner fish – what do they do?". Lochduart. 2017-06-08. Retrieved 2019-10-27.

- Brooker, Adam J; Papadopoulou, Athina; Gutierrez, Carolina; Rey, Sonia; Davie, Andrew; Migaud, Herve (2018-09-29). "Sustainable production and use of cleaner fish for the biological control of sea lice: recent advances and current challenges". Veterinary Record. 183 (12): 383. doi:10.1136/vr.104966. hdl:1893/27595. ISSN 0042-4900. PMID 30061113.

- "Lumpfish: Emerging species profile list. DFO" (PDF).

- "Labrus bergylta : Ballan Wrasse | NBN Atlas". species.nbnatlas.org. Retrieved 2019-10-28.

- Powell, Adam; Treasurer, Jim W.; Pooley, Craig L.; Keay, Alex J.; Lloyd, Richard; Imsland, Albert K.; Leaniz, Carlos Garcia de (2018). "Use of lumpfish for sea-lice control in salmon farming: challenges and opportunities". Reviews in Aquaculture. 10 (3): 683–702. doi:10.1111/raq.12194. ISSN 1753-5131.

- Dunkley, Katie; Cable, Jo; Perkins, Sarah E. (2018-02-01). "The selective cleaning behaviour of juvenile blue-headed wrasse (Thalassoma bifasciatum) in the Caribbean". Behavioural Processes. 147: 5–12. doi:10.1016/j.beproc.2017.12.005. ISSN 0376-6357. PMID 29247694.

- Morado, Nadia; Mota, Paulo G.; Soares, Marta C. (2019). "The Rock Cook Wrasse Centrolabrus exoletus Aims to Clean". Frontiers in Ecology and Evolution. 7. doi:10.3389/fevo.2019.00182. ISSN 2296-701X.

External links

![]()