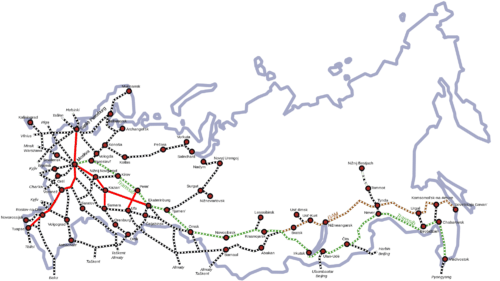

High-speed rail in Russia

High-speed rail is emerging in Russia as an increasingly popular means of transport, with the travel time from Moscow to Saint Petersburg being twice as fast via high speed rail than driving.

Experimental trainsets and early operation

Two experimental high-speed trainsets were built in 1974 designed for 200 km/h (120 mph) operation: the locomotive-hauled RT-200 ("Russkaya Troika") and the ER-200 EMU. The RT-200 set made only experimental runs in 1975 and 1980 and was discontinued due to the unavailability of the ChS-200 high-speed locomotive, which was only delivered later. The ER-200 EMU was put into regular service in 1984. In 1992 a second ER-200 trainset was built in Riga. Both sets were retired in 2009.

Lines in operation

- The Sapsan on the Moscow–Saint Petersburg Railway is Russia's highest speed railway, operating Siemens Velaro trains with a top speed of 250 km/h (155 mph).[1] The first upgraded 250 km/h service using Russian high speed trains Sapsan went into service on December 26, 2009.

- Helsinki–St. Petersburg: 200 km/h (124 mph) high-speed service using Karelian Trains Class Sm6 (Allegro) trains started on December 12, 2010, reducing travel time from 5.5 hours to 3.5 hours. The trains run at 200 km/h (124 mph) on most of the Russian part, and 220 km/h (137 mph) on a short stretch in Finland.[2]

- Moscow–Nizhny Novgorod: High-speed traffic in Nizhny Novgorod began in July 2010.[3] Two Sapsan trains make shuttle trips between Nizhny Novgorod and Moscow, and one between Nizhny Novgorod and St. Petersburg. The latter route takes 8 hours and 30 minutes, compared to the previous 14 hours.[4] Nevertheless, like the gradual speed increases of Afrosiyob in Uzbekistan, the line is technically not full HSR speed; the line has been undergoing upgrades as of 2018.

New lines under consideration

Russia is currently building the following high speed rail lines, with a combined cost of $36 billion, working out to around $33 million per kilometer:[5]

- Moscow–St Petersburg: In February 2010, RZD announced that it would unveil proposals in March 2010, for a new "European standard" high-speed line between St Petersburg and Moscow.[6] The new line would be built to Russian gauge and would probably be built parallel to the existing line.[6] At an event on 1 April 2010, it was announced that the new Moscow – St. Petersburg high-speed line would allow trains to run at speeds up to 400 km/h (249 mph). The total journey time would be cut from 3h 45m to 2h 40m. The new line is expected to make extensive use of bridges, tunnels and viaducts. Finance will be provided by a public-private finance vehicle. The line is expected to carry 14 million people in its first year, with capacity for 47 million passengers annually. Representatives from many other high-speed lines will be consulted, in an effort to avoid construction delays and design flaws.[7] Apart from faster travel times, the new line would increase capacity, since the current line is congested and there is only room for a limited number of high speed trains. It would also improve safety, since trains currently pass some level crossings at 250 km/h. The majority of the construction of the 657 km line is scheduled between 2022 and 2025, and the project is due to open in 2026.[5]

- Moscow-Nizhny Novgorod: This leg of the high speed rail project is due to open in 2024, and is 421 kilometers long.[5]

Russia has the following lines under consideration:

- Moscow–Kazan High-Speed Rail Project: The call to build this 770 kilometers, 2018 completed rail line that would connect Kazan and Moscow was first announced by President Vladimir Putin in the Economic Forum at St. Petersburg in 2013. Plans for the railroad estimate that it will be the first true high-speed line in Russia with trains operating at up to 400 kilometers per hour. A rail trip from Moscow to Kazan which today takes a close to 13 hours trip, would be reduced to 3.5 hours. With the Moscow – St. Petersburg line on the other hand trains run at up to 240 kilometers per hour.[8] As of 2020, construction has still not begun, and president Vladimir Putin has given ambivalent answers regarding the status of the project which allude to projected lack of return on the investment.

- Moscow–Rostov line: A new line with the capacity for high speed rail was approved due to the old line passing through Ukraine and is expected to be operational by 2018,[9] but the project ended up having a top speed of 160 km/h, failing to qualify the line as high speed rail.[10]

- Moscow–Riga:[11] Under consideration, but low priority.

- Moscow-Minsk: In 2019 a new international "high speed" train service was announced between Minsk and Russia, but the estimated journey time of 6 hours for 700 kilometers yields a service of 120 km/h, which fails to qualify as true high speed rail.[12]

- In 2018 Chechen leaders requested federal financing of high speed rail from Rostov to Krasnodar, Grosny, Maikop, Mineralnye Vody, Makhachkala, and other Northern Caucasus Republics. Preliminary cost estimates are nearly $13 billion. Economic benefits would include a new freight corridor from the Black Sea to the Caspian Sea, but experts seem to doubt the economic feasibility of the project.[13]

Criticism from rural areas

Since the Sapsan service between Moscow and St Petersburg shares tracks with regular passenger trains and freight trains, it has been widely reported that its introduction has resulted in the cancellation of a number of more affordable long-distance passenger and commuter trains, and long delays for many other trains that continue to run. Moreover, the numerous level crossings along the line have to be kept closed to road traffic for longer for the high-speed trains than for regular ones (the crossing is closed 15 minutes ahead of a fast train passing through); the resulting delays have been criticized by motorists and bus passengers, as well as by ambulance and fire services in towns along the railway. In some small towns dependent on commuter trains for connection with the outside world, and on level crossings for local travel, such as Chupriyanovka (Чуприяновка; population 2,500) near Tver, local officials have expressed the sentiment that "our town is cut into two halves for over seven hours each day" and that "we have been cut off from the outside world". Overall, the feeling is widespread that the new service benefits the country's moneyed elite, while severely inconveniencing the majority of the population in the regions through which the railway runs.[14] As of 2015, the additional tracks for high speed trains[15] and over-crossings were built.

References

- "First high speed train Sapsan arrived in St Petersburg from Moscow". Russia InfoCentre. 26 December 2008.

- "Allegro launch cuts Helsinki - St Petersburg journey times". Railway Gazette International. 13 December 2010.

- "Sapsan reaches Nizhny Novgorod". Railway Gazette International. 2 August 2010.

- "Technical safety of 'Sapsan' high-speed train ensured 100% - Russian Railroads". Retrieved 2010-01-24. (dead link dec 2010)

- Times, The Moscow (2019-10-23). "Russia's New High Speed Rail Route to Cost $36Bln". The Moscow Times. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "Russia to announce high speed line plan". Railway Gazette International. 17 February 2010.

- "RZD launches Moscow - St Petersburg high speed line project". Railway Gazette International. 2 April 2010.

- Panin, Alexander (4 March 2014). "Potential Investors Get Preview of Moscow-Kazan High Speed Rail Project". The Moscow Times.

- "Russia approves railroad to bypass Ukraine". RT Business. 21 September 2015.

- 2017-08-08T08:56:55+01:00. "Russia completes railway to bypass Ukraine". Railway Gazette International. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Petrova, Alla (8 June 2011). "Augulis: high-speed railroad project between Riga and Moscow must be self sufficient". The Baltic Course.

- "New high-speed train service to connect Minsk, Moscow in 2020". eng.belta.by. 2019-12-13. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- "High-speed Railway from Krasnodar to Grozny". Georgia Today on the Web. Retrieved 2020-03-26.

- Axel Gyldén (2010-07-23), "Le TGV russe, symbole d'un pays à deux vitesses", L'Express (in French)

- http://www.netall.ru/gnn/130/575/873531.html