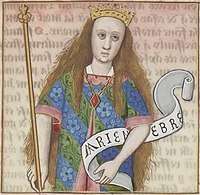

Mariamne I

Mariamne I (died 29 BCE), also called Mariamne the Hasmonean, was a Hasmonean princess and the second wife of Herod the Great. She was known for her great beauty, as was her brother Aristobulus III. Herod's fear of his rivals, the Hasmoneans, led him to execute all of the prominent members of the family, including Mariamne.

Her name is spelled Μαριάμη (Mariame) by Josephus, but in some editions of his work the second m is doubled (Mariamme). In later copies of those editions the spelling was dissimilated to its now most common form, Mariamne. In Hebrew, Mariamne is known as מִרְיָם, (Miriam), as in the traditional, Biblical name (see Miriam, the sister of Moses and Aaron).

Family

Mariamne was the daughter of the Hasmonean Alexandros, also known as Alexander of Judaea, and thus one of the last heirs to the Hasmonean dynasty of Judea.[1] Mariamne's only sibling was Aristobulus III. Her father, Alexander of Judaea, the son of Aristobulus II, married his cousin Alexandra, daughter of his uncle Hyrcanus II, in order to cement the line of inheritance from Hyrcanus and Aristobulus, but the inheritance soon continued the blood feud of previous generations, and eventually led to the downfall of the Hasmonean line. By virtue of her parents' union, Mariamne claimed Hasmonean royalty on both sides of her family lineage.

Her mother, Alexandra, arranged for her betrothal to Herod in 41 BCE after Herod agreed to a Ketubah with Mariamne's parents. The two were wed four years later (37 BCE) in Samaria. Mariamne bore Herod four children: two sons, Alexandros and Aristobulus (both executed in 7 BCE), and two daughters, Salampsio and Cypros. A fifth child (male), drowned at a young age – likely in the Pontine Marshes near Rome, after Herod's sons had been sent to receive educations in Rome in 20 BCE.

Josephus writes that it was because of Mariamne's vehement insistence that Herod made her brother Aristobulos a High Priest. Aristobulos, who was not even eighteen years old, drowned (in 36 BCE) within a year of his appointment; Alexandra, his mother, blamed Herod. Alexandra wrote to Cleopatra, begging her assistance in avenging the boy's murder. Cleopatra in turn urged Mark Antony to punish Herod for the crime, and Antony sent for him to make his defense. Herod left his young wife in the care of his uncle Joseph, along with the instructions that if Antony should kill him, Joseph should kill Mariamne. Herod believed his wife to be so beautiful that she would become engaged to another man after his death and that his great passion for Mariamne prevented him from enduring a separation from her, even in death. Joseph became familiar with the queen and eventually divulged this information to her and the other women of the household, which did not have the hoped-for effect of proving Herod's devotion to his wife. Rumors soon circulated that Herod had been killed by Antony, and Alexandra persuaded Joseph to take Mariamne and her to the Roman legions for protection. However, Herod was released by Antony and returned home, only to be informed of Alexandra's plan by his mother and sister, Salome. Salome also accused Mariamne of committing adultery with Joseph, a charge which Herod initially dismissed after discussing it with his wife. After Herod forgave her, Mariamne inquired about the order given to Joseph to kill her should Herod be killed, and Herod then became convinced of her infidelity, saying that Joseph would only have confided that to her were the two of them intimate. He gave orders for Joseph to be executed and for Alexandra to be confined, but Herod did not punish his wife.

Because of this conflict between Mariamne and Salome, when Herod visited Augustus in Rhodes in 31 BCE, he separated the women. He left his sister and his sons in Masada while he moved his wife and mother-in-law to Alexandrium. Again, Herod left instructions that should he die, the charge of the government was to be left to Salome and his sons, and Mariamne and her mother were to be killed. Mariamne and Alexandra were left in the charge of another man named Sohemus, and after gaining his trust again learned of the instructions Herod provided should harm befall him. Mariamne became convinced that Herod did not truly love her and resented that he would not let her survive him. When Herod returned home, Mariamne treated him coldly and did not conceal her hatred for him. Salome and her mother preyed on this opportunity, feeding Herod false information to fuel his dislike. Herod still favored her; but she refused to have sexual relations with him and accused him of killing her grandfather, Hyrcanus II, and her brother. Salome insinuated that Mariamne planned to poison Herod, and Herod had Mariamne's favorite eunuch tortured to learn more. The eunuch knew nothing of a plot to poison the king, but confessed the only thing he did know: that Mariamne was dissatisfied with the king because of the orders given to Sohemus. Outraged, Herod called for the immediate execution of Sohemus, but permitted Mariamne to stand trial for the alleged murder plot. To gain favor with Herod, Mariamne's mother even implied Mariamne was plotting to commit lèse majesté. Mariamne was ultimately convicted and executed in 29 BCE.[2] Herod grieved for her for many months.

Children

- son Alexander, executed 7 BCE

- son Aristobulus IV, executed 7 BCE

- daughter Salampsio

- daughter Cypros

Talmudic reference

There is a Talmudic passage concerning the marriage and death of Mariamne, although her name is not mentioned. When the whole house of the Hasmoneans had been rooted out, she threw herself from a roof and was killed. She committed suicide because Herod had spared her life, so that he could marry her. If he were to marry her, then he would be able to claim that he was not actually a slave, but rather that he had royal blood.[3] Out of love for her, Herod is said to have kept her body preserved in honey for seven years. There is an opinion that he would use her to fulfill animalistic desires[4] In the Talmud this sort of action is called a "deed of Herod".[5] Josephus relates also that after her death Herod tried in hunting and banqueting to forget his loss, but that even his strong nature succumbed and he fell ill in Samaria, where he had made Mariamne his wife.[6] The Mariamne Tower in Jerusalem, built by Herod, was without doubt named after her; it was called also "Queen".[7]

Mariamne in the arts

She is remembered in De Mulieribus Claris, a collection of biographies of historical and mythological women by the Florentine author Giovanni Boccaccio, composed in 1361–62. It is notable as the first collection devoted exclusively to biographies of women in Western literature.[8]. From the Renaissance to contemporary times, there has been a long tradition of works of art (dramas, operas, novels, etc.) devoted to Mariamne and her relationship with Herod the Great.[9] The list includes:

- Marianna (1565), an Italian drama by Lodovico Dolce

- The Tragedy of Mariam, the Faire Queene of Jewry (1613) an English drama by Elizabeth Tanfield Cary

- Herod and Antipater, with the Death of Faire Mariam (1622), an English drama by Gervase Markham and William Sampson

- Mariamne (1636), a French drama by François Tristan l'Hermite

- El mayor monstruo los celos (1637) a Spanish drama by Pedro Calderon de la Barca

- La mort des enfants d’Hérode; ou, Suite de Mariamne (1639), a French drama by Gathier de Costes de la Calprenède

- Herod and Mariamne (1673), an English drama by Samuel Pordage

- Herodes en Mariamne (1685), a Dutch translation of Tristan l'Hermit's play by Katharina Lescailje

- La Mariamne (1696), an Italian opera by Giovanni Maria Ruggeri (mus.) and Lorenzo Burlini (libr.)

- Mariamne (1723), an English drama by Elijah Fenton

- Mariamne (1723), a French drama by Voltaire

- Mariamne (1725), a French drama by Augustin Nadal

- La Marianna (1785), an Italian ballet by Giuseppe Banti (chor.)

- Marianne (1796), a French opera by Nicolas Dalayrac (mus.) and Benoît-Joseph Marsollier (libr.)

- "Herod’s Lament for Mariamne" (1815), an English song by Isaac Nathan (mus.) and George Byron (libr.)

- Erode; ossia, Marianna (1825), Italian opera by Saverio Mercadante (mus.) and Luigi Ricciuti (libr.)

- Herodes und Mariamne (1850), a German drama by Christian Friedrich Hebbel

- Mariamne Leaving the Judgment Seat of Herod (1887), a painting by John William Waterhouse

- "Herod and Mariamne" (1888), an English poem by Amelie Rives

- Myriam ha-Hashmonayith (1891), a Yiddish drama by Moses Seiffert

- Tsar Irod I tsaritsa Mariamna (1893), a Russian drama by Dmitri Alexandrov

- "Mariamne" (1911), an English poem by Thomas Sturge Moore

- Herodes und Mariamne (1922), incidental music by Karol Rathaus

- Lied der Mariamne (ohne Worte) (1927), incidental music by Mikhail Gnesin

- Hordos u-Miryam (1935), a Hebrew novel by Aaron Orinowsky

- Herod and Mariamne (1938), an English drama by Clemence Dane

- Mariamne (1967), a Swedish novel by Pär Lagerkvist

See also

- 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees for the family history.

- Hasmonean Kingdom for the history the Hasmonean dynasty.

- Mariamne for the derivation of her name.

Notes

- Josephus records a daughter of Antigonus, the last Hasmonean king, was married to Antipater III and with him during his trial before Varus in 5 BCE. See Antiquities, Book XVII, Chapter 5:2

- Josephus, Jewish Antiquities 15.7.4–6.

- B. B. 3b

- Ib.; S. Geiger, in "Oẓar Neḥmad", iii. 1

- Sanh. 66b

- "Ant." xv. 7, § 7

- Βασιλίς "B. J." ii. 17, § 8; v. 4, § 3

- Boccaccio (2003), p. xi

- G. Boccaccini, Portraits of Middle Judaism in Scholarship and Arts (Turin: Zamorani 1992); M. J. Valency, The Tragedies of Herod and Mariamne (New York 1940).

Kiddushin 70 B

References

- Josephus. Antiquities of the Jews. 15.23–31, 61–85, 185, 202–246; Jewish War 1.241, 262, 431–444.

- Gabriele Boccaccini (1992). Portraits of Middle Judaism in Scholarship and Arts. Turin: Zamorani. ISBN 9788871580210.

- Maurice J. Valency (1940). The Tragedies of Herod and Mariamne. New York: Columbia University Press.

External links

- Mariamne entry in historical sourcebook by Mahlon H. Smith

- Mariamne entry in Jewish Encyclopedia by Richard Gottheil and Samuel Krauss

- Kittymunson.com, the Hasmonean Maccabeus Mariamne family tree