Hermaphrodite

In reproductive biology, a hermaphrodite (/hɜːrˈmæfrədaɪt/) is an organism that has complete or partial reproductive organs and produces gametes normally associated with both male and female sexes.[1] Many taxonomic groups of animals (mostly invertebrates) do not have separate sexes.[2] In these groups, hermaphroditism is a normal condition, enabling a form of sexual reproduction in which either partner can act as the "female" or "male". For example, the great majority of tunicates, pulmonate snails, opisthobranch snails, earthworms, and slugs are hermaphrodites. Hermaphroditism is also found in some fish species and to a lesser degree in other vertebrates. Most plants are also hermaphrodites.

Historically, the term hermaphrodite has also been used to describe ambiguous genitalia and gonadal mosaicism in individuals of gonochoristic species, especially human beings. The word intersex has come into usage for humans, since the word hermaphrodite is considered to be misleading and stigmatizing,[3][4] as well as "scientifically specious and clinically problematic."[5]

A rough estimate of the number of hermaphroditic animal species is 65,000.[6] The percentage of animal species that are hermaphroditic is about 5%. (Although the current estimated total number of animal species is about 7.7 million, the study,[6] which estimated the number, 65,000, used an estimated total number of animal species, 1,211,577 from "Classification phylogénétique du vivant (Vol. 2)" - Lecointre and Le Guyader (2001)). Most hermaphroditic species exhibit some degree of self-fertilization. The distribution of self-fertilization rates among animals is similar to that of plants, suggesting that similar processes are operating to direct the evolution of selfing in animals and plants.[6]

Etymology

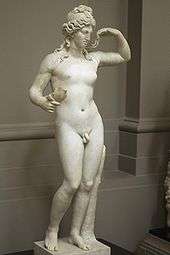

The term derives from the Latin: hermaphroditus, from Ancient Greek: ἑρμαφρόδιτος, romanized: hermaphroditos,[7] which derives from Hermaphroditus (Ἑρμαφρόδιτος), the son of Hermes and Aphrodite in Greek mythology. According to Ovid, he fused with the nymph Salmacis resulting in one individual possessing physical traits of male and female sexes;[8] according to the earlier Diodorus Siculus, he was born with a physical body combining male and female sexes.[9] The word hermaphrodite entered the English lexicon as early as the late fourteenth century.[10] Alexander ab Alexandro stated, using the term hermaphrodite, that the people who bore the sexes of both man and woman were regarded by the Athenians and the Romans as monsters, and thrown into the sea at Athens and into the Tiber at Rome.[11]

Zoology

Sequential hermaphrodites

Sequential hermaphrodites (dichogamy) occur in species in which the individual is born as one sex, but can later change into the opposite sex.[12] This contrasts simultaneous hermaphrodites, in which an individual may possess fully functional male and female genitalia. Sequential hermaphroditism is common in fish (particularly teleost fish) and many gastropods (such as the common slipper shell), and some flowering plants. Sequential hermaphrodites can only change sex once.[13] Sequential hermaphroditism can best be understood in terms of behavioral ecology and evolutionary life history theory, as described in the size-advantage mode[14] first proposed by Michael T. Ghiselin[15] which states that if an individual of a certain sex could significantly increase its reproductive success after reaching a certain size, it would be to their advantage to switch to that sex.

Sequential hermaphrodites can be divided into three broad categories:

- Protandry: Where an organism is born as a male, and then changes sex to a female.[12]

- Example: The clownfish (genus Amphiprion) are colorful reef fish found living in symbiosis with sea anemones. Generally one anemone contains a 'harem', consisting of a large female, a smaller reproductive male, and even smaller non-reproductive males. If the female is removed, the reproductive male will change sex and the largest of the non-reproductive males will mature and become reproductive. It has been shown that fishing pressure can change when the switch from male to female occurs, since fishermen usually prefer to catch the larger fish. The populations are generally changing sex at a smaller size, due to natural selection.

- Protogyny: Where the organism is born as a female, and then changes sex to a male.[12]

- Example: wrasses (Family Labridae) are a group of reef fish in which protogyny is common. Wrasses also have an uncommon life history strategy, which is termed diandry (literally, two males). In these species, two male morphs exists: an initial phase male and a terminal phase male. Initial phase males do not look like males and spawn in groups with other females. They are not territorial. They are, perhaps, female mimics (which is why they are found swimming in group with other females). Terminal phase males are territorial and have a distinctively bright coloration. Individuals are born as males or females, but if they are born males, they are not born as terminal phase males. Females and initial phase males can become terminal phase males. Usually, the most dominant female or initial phase male replaces any terminal phase male when those males die or abandon the group.

- Bidirectional Sex Changers: where an organism has female and male reproductive organs, but act as either female or male during different stages in life.[12]

- Example: Lythrypnus dalli (Family Lythrypnus) are a group of coral reef fish in which bidirectional sex change occurs. Once a social hierarchy is established a fish changes sex according to its social status, regardless of the initial sex, based on a simple principle: if the fish expresses subordinate behavior then it changes its sex to female, and if the fish expresses dominant or not subordinate behavior then the fish changes its sex to male.[16]

Dichogamy can have both conservation-related implications for humans, as mentioned above, as well as economic implications. For instance, groupers are favoured fish for eating in many Asian countries and are often aquacultured. Since the adults take several years to change from female to male, the broodstock are extremely valuable individuals.

Simultaneous hermaphrodites

A simultaneous (or synchronous) hermaphrodite (or homogamous) is an adult organism that has both male and female sexual organs at the same time.[12] Self-fertilization often occurs.

- Reproductive system of gastropods: Pulmonate land snails and land slugs are perhaps the best-known kind of simultaneous hermaphrodite, and are the most widespread of terrestrial animals possessing this sexual polymorphism. Sexual material is exchanged between both animals via spermatophore, which can then be stored in the spermatheca. After exchange of spermatozoa, both animals will lay fertilized eggs after a period of gestation; then the eggs will proceed to hatch after a development period. Snails typically reproduce in early spring and late autumn.

- Banana slugs are one example of a hermaphroditic gastropod. Mating with a partner is more desirable biologically, as the genetic material of the resultant offspring is varied, but if mating with a partner is not possible, self-fertilization is practiced. The male sexual organ of an adult banana slug is quite large in proportion to its size, as well as compared to the female organ. It is possible for banana slugs, while mating, to become stuck together. If a substantial amount of wiggling fails to separate them, the male organ will be bitten off (using the slug's radula), see apophallation. If a banana slug has lost its male sexual organ, it can still mate as a female, making its hermaphroditic quality a valuable adaptation.

- The species of colourful sea slugs Goniobranchus reticulatus is hermaphroditic, with both male and female organs active at the same time during copulation. After mating, the external portion of the penis detaches, but is able to regrow within 24 hours.[17][18]

- Hamlets, unlike other fish, seem quite at ease mating in front of divers, allowing observations in the wild to occur readily. They do not practice self-fertilization, but when they find a mate, the pair takes turns between which one acts as the male and which acts as the female through multiple matings, usually over the course of several nights.

- Earthworms are another example of a simultaneous hermaphrodite. Although they possess ovaries and testes, they have a protective mechanism against self-fertilization. Sexual reproduction occurs when two worms meet and exchange gametes, copulating on damp nights during warm seasons. Fertilized eggs are protected by a cocoon, which is buried on or near the surface of the ground.

- The free-living hermaphroditic nematode Caenorhabditis elegans reproduces primarily by self-fertilization, but infrequent out-crossing events occur at a rate of approximately 1%.[19]

- The mangrove killifish (Kryptolebias marmoratus) is a species of fish that lives along the east coast of North, Central and South America. These fish are simultaneous hermaphrodites. K. marmoratus produces eggs and sperm by meiosis and routinely reproduces by self-fertilization. Each individual hermaphrodite normally fertilizes itself when an egg and sperm produced by an internal organ unite inside the fish's body.[20]

Pseudohermaphroditism

When spotted hyenas were first discovered by explorers, they were thought to be hermaphrodites. Early observations of spotted hyenas in the wild led researchers to believe that all spotted hyenas, male and female, were born with what appeared to be a penis. The apparent penis in female spotted hyenas is in fact an enlarged clitoris, which contains an external birth canal.[21][22] It can be difficult to determine the sex of wild spotted hyenas until sexual maturity, when they may become pregnant. When a female spotted hyena gives birth, they pass the cub through the cervix internally, but then pass it out through the elongated clitoris.[23]

Humans

| Intersex topics |

|---|

|

|

Medicine and biology |

|

History and events |

.jpg)

Hermaphrodite is used in older literature to describe any person whose physical characteristics do not neatly fit male or female classifications, but some people advocate to replace the term with intersex.[26][27] Intersex describes a wide variety of combinations of what are considered male and female biology. Intersex biology may include, for example, ambiguous-looking external genitalia, karyotypes that include mixed XX and XY chromosome pairs (46XX/46XY, 46XX/47XXY or 45X/XY mosaic).

Clinically, medicine currently describes intersex people as having disorders of sex development, a term vigorously contested.[28][29] This is particularly because of a relationship between medical terminology and medical intervention.[30] Intersex civil society organizations, and many human rights institutions,[31][32] have criticized medical interventions designed to make intersex bodies more typically male or female.

Some people who are intersex, such as some of those with androgen insensitivity syndrome, outwardly appear completely female or male, frequently without realizing they are intersex. Other kinds of intersex conditions are identified immediately at birth because those with the condition have a sexual organ larger than a clitoris and smaller than a penis.

Some humans were historically termed true hermaphrodites if their gonadal tissue contained both testicular and ovarian tissue, or pseudohermaphrodites if their external appearance (phenotype) differed from sex expected from internal gonads. This language has fallen out of favor due to misconceptions and pejorative connotations associated with the terms,[33] and also a shift to nomenclature based on genetics.

Intersex is in some caused by unusual sex hormones; the unusual hormones may be caused by an atypical set of sex chromosomes. One possible pathophysiologic explanation of intersex in humans is a parthenogenetic division of a haploid ovum into two haploid ova. Upon fertilization of the two ova by two sperm cells (one carrying an X chromosome and the other carrying a Y chromosome), the two fertilized ova are then fused together resulting in a person having dual genitalial, gonadal (ovotestes) and genetic sex. Another common cause of being intersex is the crossing over of the SRY from the Y chromosome to the X chromosome during meiosis. The SRY is then activated in only certain areas, causing development of testes in some areas by beginning a series of events starting with the upregulation of SOX9, and in other areas not being active (causing the growth of ovarian tissues). Thus, testicular and ovarian tissues will both be present in the same individual.[34]

Fetuses before sexual differentiation are sometimes described as female by doctors explaining the process.[35] This is technically not true. Before this stage, humans are simply undifferentiated and possess a Müllerian duct, a Wolffian duct, and a genital tubercle.

Botany

Hermaphrodite is used in botany to describe a flower that has both staminate (male, pollen-producing) and carpellate (female, ovule-producing) parts. This condition is seen in many common garden plants. A closer analogy to hermaphroditism in botany is the presence of separate male and female flowers on the same individual—such plants are called monoecious. Monoecy is especially common in conifers, but occurs in only about 7% of angiosperm species.[36] The condition also occurs in some algae.[37] In addition, some plants can change their sex throughout their lifetime. This process is called Sequential hermaphroditism.

In fiction

Hermaphroditic life forms in fiction include the Hutts in Star Wars (as elaborated in spin-off novels), Hermats in Peter David's Star Trek: New Frontier series, and Asari in the Mass Effect game. The Trill symbionts in Star Trek are also notable as a species that melds with hosts of either sex.

References

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary Archived 2011-08-07 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 28 June 2011

- "hermaphroditism". Encyclopædia Britannica Online. Archived from the original on 8 March 2013. Retrieved 9 April 2013.

- Dreger, Alice Domurat (1999). Intersex in the age of ethics (Ethics in Clinical Medicine Series ed.). Hagerstown, Md.: Univ. Publ. Group. ISBN 978-1555721008.

- "Is a person who is intersex a hermaphrodite?". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 1 July 2013. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Herndon, April. "Getting Rid of "Hermaphroditism" Once and For All". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 27 September 2011. Retrieved 2 October 2011.

- Jarne P, Auld JR (September 2006). "Animals mix it up too: the distribution of self-fertilization among hermaphroditic animals". Evolution. 60 (9): 1816–24. doi:10.1554/06-246.1. PMID 17089966.

- "Definition of hermaphroditus". Numen: The Latin Lexicon. Archived from the original on 6 November 2014. Retrieved 19 July 2013.

- Ovid, Metamorphoses, Book IV: The story of Hermaphroditus and Salmacis.

- "LacusCurtius • Diodorus Siculus — Book IV Chapters 1‑7". penelope.uchicago.edu.

- Oxford English Dictionary, 1st edn, s.v. hermaphrodite, n. and adj.; "Online Etymology Dictionary". Archived from the original on 5 November 2013. Retrieved 3 June 2012.

- "Hermaphrodite". quod.lib.umich.edu. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02. Retrieved 2015-04-01.

- Barrows, Edward M. (2001). Animal behavior desk reference: a dictionary of animal behavior, ecology, and evolution (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Fla: CRC Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-8493-2005-7. OCLC 299866547.

- Pandian, T. J. (2 September 2011). Sex Determination in Fish. CRC Press. ISBN 9781439879191. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017 – via Google Books.

- Warner, Robert R (June 1988). "Sex change and the size-advantage model". Trends in Ecology and Evolution. 3 (6): 133–136. doi:10.1016/0169-5347(88)90176-0. PMID 21227182.

- Ghiselin, Michael T. (1969). "The evolution of hermaphroditism among animals". Quarterly Review of Biology. 44 (2): 189–208. doi:10.1086/406066. PMID 4901396.

- Rodgers, E.W.; Early, R.L.; Grober, M.S. (2007). "Social status determines sexual phenotype in the bi-directional sex changing bluebanded goby Lythrypnus dalli". J Fish Biol. 70 (6): 1660–1668. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.2007.01427.x.

- Rebecca Morelle (12 February 2013). "Sea slug's 'disposable penis' surprises". BBC News.

- Sekizawa, A.; Seki, S.; Tokuzato, M.; Shiga, S.; Nakashima, Y. (2013). "Disposable penis and its replenishment in a simultaneous hermaphrodite". Biology Letters. 9 (2): 20121150. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2012.1150. PMC 3639767. PMID 23407499.

- Barrière A, Félix MA (July 2005). "High local genetic diversity and low outcrossing rate in Caenorhabditis elegans natural populations". Curr. Biol. 15 (13): 1176–84. arXiv:q-bio/0508003. doi:10.1016/j.cub.2005.06.022. PMID 16005289.

- Sakakura, Y., Soyano, K., Noakes, D.L.G. & Hagiwara, A. (2006). Gonadal morphology in the self-fertilizing mangrove killifish, Kryptolebias marmoratus. Ichthyological Research, Vol. 53, pp. 427-430

- "The Painful Realities of Hyena Sex". Archived from the original on 2012-11-19.

- "Hyena Graphic". EurekAlert!. Archived from the original on 2011-03-10.

- "Hermaphrodite Hyenas?". Archived from the original on 2010-11-23.

- "LAKAPATI: The "Transgender" Tagalog Deity? Not so fast…". THE ASWANG PROJECT. Retrieved 2019-07-03.

- Schultheiss, Herrmann & Jonas 2006, p. 358.

- Dreger, Alice D.; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). "Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale". Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. 18 (8): 729–33. doi:10.1515/jpem.2005.18.8.729. PMID 16200837.

- "Getting Rid of "Hermaphroditism"". Intersex Society of North America. Archived from the original on 3 January 2018. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- Davis, Georgiann (2011). McGann, PJ; Hutson, David J. (eds.). "DSD is a Perfectly Fine Term": Reasserting Medical Authority through a Shift in Intersex Terminology". Sociology of Diagnosis (Advances in Medical Sociology). 12: 155–182.

- Holmes, Morgan (2011). "The Intersex Enchiridion: Naming and Knowledge in the Clinic". Somatechnics. 1 (2): 87–114. doi:10.3366/soma.2011.0026.

- Androgen Insensitivity Support Syndrome Support Group Australia; Intersex Trust Aotearoa New Zealand; Organisation Intersex International Australia; Black, Eve; Bond, Kylie; Briffa, Tony; Carpenter, Morgan; Cody, Candice; David, Alex; Driver, Betsy; Hannaford, Carolyn; Harlow, Eileen; Hart, Bonnie; Hart, Phoebe; Leckey, Delia; Lum, Steph; Mitchell, Mani Bruce; Nyhuis, Elise; O'Callaghan, Bronwyn; Perrin, Sandra; Smith, Cody; Williams, Trace; Yang, Imogen; Yovanovic, Georgie (March 2017), Darlington Statement, archived from the original on 2017-03-22, retrieved March 21, 2017

- UN Committee against Torture; UN Committee on the Rights of the Child; UN Committee on the Rights of People with Disabilities; UN Subcommittee on Prevention of Torture and other Cruel, Inhuman or Degrading Treatment or Punishment; Juan Méndez, Special Rapporteur on torture and other cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment or punishment; Dainius Pῡras, Special Rapporteur on the right of everyone to the enjoyment of the highest attainable standard of physical and mental health; Dubravka Šimonoviæ, Special Rapporteur on violence against women, its causes and consequences; Marta Santos Pais, Special Representative of the UN Secretary-General on Violence against Children; African Commission on Human and Peoples' Rights; Council of Europe Commissioner for Human Rights; Inter-American Commission on Human Rights (October 24, 2016), "Intersex Awareness Day – Wednesday 26 October. End violence and harmful medical practices on intersex children and adults, UN and regional experts urge", Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights, archived from the original on November 21, 2016CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Council of Europe; Commissioner for Human Rights (April 2015), Human rights and intersex people, Issue Paper, archived from the original on 2016-01-06

- Dreger, Alice D.; Chase, Cheryl; Sousa, Aron; Gruppuso, Phillip A.; Frader, Joel (18 August 2005). "Changing the Nomenclature/Taxonomy for Intersex: A Scientific and Clinical Rationale" (PDF). Journal of Pediatric Endocrinology and Metabolism. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 December 2016. Retrieved 27 July 2016.

- Margarit, E.; Coll, M. D.; Oliva, R.; Gómez, D.; Soler, A.; Ballesta, F. (2000). "SRY gene transferred to the long arm of the X chromosome in a Y-positive XX true hermaphrodite". American Journal of Medical Genetics. 90 (1): 25–28. doi:10.1002/(SICI)1096-8628(20000103)90:1<25::AID-AJMG5>3.0.CO;2-5. PMID 10602113.

- Leyner, Mark; Goldberg M.D., Billy (2005). Why Do Men Have Nipples?: Hundreds of Questions You'd Only Ask a Doctor After Your Third Martini. New York: Three Rivers Press. ISBN 978-1-4000-8231-5. OCLC 57722472.

- Molnar, Sebastian (17 February 2004). "Plant Reproductive Systems". Evolution and the Origins of Life. Geocities.com. Archived from the original on 2009-10-22. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- Newton, L. 1931 A Handbook of the British Seaweeds. British Museum, London p.225

Further reading

- "Bony Fishes: Reproduction". SeaWorld/Busch Gardens Animal Infobooks. Busch Entertainment Corporation. 2009. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 12 September 2009.

- Discovery Health Channel, (2007) "I Am My Own Twin"

- Kyu-Rae Kim M.D.; Youngmee Kwon M.D.; Jae Young Joung M.D.; Kun Suk Kim M.D.; Alberto G Ayala M.D.; Jae Y Ro M.D. (2002). "True Hermaphroditism and Mixed Gonadal Dysgenesis in Young Children: A Clinicopathologic Study of 10 Cases". Modern Pathology. 15 (10): 1013–1019. doi:10.1097/01.MP.0000027623.23885.0D. ISSN 0893-3952. OCLC 357415945. PMID 12379746.

- Randall, John E. (2005). Reef and Shore Fishes of the South Pacific: New Caledonia to Tahiti and the Pitcairn Islands. Honolulu, Hawaii: University of Hawaii Press. pp. 346, 387. ISBN 978-0-8248-2698-7. OCLC 52152732.

- Chase, Cheryl (1998). "Affronting Reason". In Atkins, Dawn (ed.). Looking Queer: Body Image and Identity in Lesbian, Bisexual, Gay, and Transgender Communities. New York: Haworth Press. pp. 205–219. ISBN 978-1-56023-931-4. OCLC 38519315.

- Fausto-Sterling, Anne (12 March 1993). "How Many Sexes Are There?". The New York Times. New York. p. Op–Ed., reprinted in: Harwood, Sterling, ed. (1996). Business As Ethical and Business As Usual: Text, Readings, and Cases. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Pub. pp. 168–170. ISBN 978-0-534-54251-1. OCLC 141382073.

- Grumbach, Melvin M.; Conte, F. A. (1998). "Disorders of sex differentiation". In Williams, Robert Hardin; Wilson, Jean D (eds.). Williams Textbook of Endocrinology. Philadelphia: Saunders. pp. 1303–1425. ISBN 978-0-7216-6152-0. OCLC 35364729.

- Schultheiss, Dirk; Herrmann, Thomas; Jonas, Udo (March 2006). "Early Photo-Illustration of a Hermaphrodite by the French Photographer and Artist Nadar in 1860". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 3 (2): 355–360. doi:10.1111/j.1743-6109.2005.00157.x. PMID 16490032.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) (subscription required)

External links

| Look up hermaphrodite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Hermaphrodite. |