Hall house

The hall house is a type of vernacular house traditional in many parts of England, Wales, Ireland and lowland Scotland, as well as northern Europe, during the Middle Ages, centring on a hall. Usually timber-framed, some high status examples were built in stone.

Unaltered hall houses are almost unknown. Where they have survived, they have almost always been significantly changed and extended by successive owners over the generations.

Origins

In Old English, a "hall" is simply a large room enclosed by a roof and walls, and in Anglo-Saxon England simple one-room buildings, with a single hearth in the middle of the floor for cooking and warmth, were the usual residence of a lord of the manor and his retainers. The whole community was used to eating and sleeping in the hall. This is the hall as Beowulf understood it. Over several centuries the hall developed into a building which provided more than one room, giving some privacy to its more important residents.[1]

A significant house needs both public and private areas. The public area is the place for living: cooking, eating, meeting and playing, while private space is for withdrawing and for storing valuables. A source of heat is required, and in northern latitudes walls are also needed to keep the weather out and to keep in the heat.[2] By about 1400, in lowland Britain, with changes in settlement patterns and agriculture, people were thinking of houses as permanent structures rather than temporary shelter. According to the locality, they built stone or timber-framed houses with wattle and daub or clay infill. The designs were copied by their neighbours and descendants in the tradition of vernacular architecture. [lower-alpha 1] They were sturdy and some have survived over five hundred years. Hall houses built after 1570 are rare.[4]

The open hearth found in a hall house created heat and smoke. A high ceiling drew the smoke upwards, leaving a relatively smoke-free void beneath.[5] [6] Later hall houses were built with chimneys and flues. In earlier ones, these were added as alterations and additional flooring often installed. This, and the need for staircases to reach each of the upper storeys, led to much innovation and variety in floor plans. The hall house, having started in the Middle Ages as a home for a lord and his community of retainers, permeated to the less well-off during the early modern period. During the sixteenth century, the rich crossed what Brunskill describes as the "polite threshold" and became more likely to employ professionals to design their homes.[7]

General description

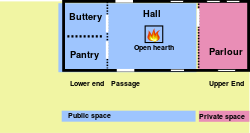

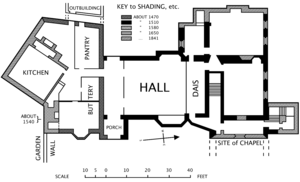

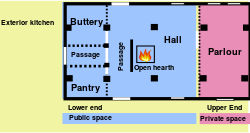

In its earliest and simplest form the medieval hall house would be a four-bay cruck-framed structure, with the open hall taking up the two bays in the middle of the building. An open hearth would be in the middle of the hall, its smoke rising to a vent in the roof. Two external doors on each side of the hall formed a cross passage. One end bay at the "screens end" or "lower end" of the hall would contain two rooms commonly called the pantry, used for storing food, and the buttery used for storing drink. These were intentionally unheated. The rooms in the "upper end" bay formed the private space. This layout was analogous to that found in the great houses of the day, the difference being merely that of scale.

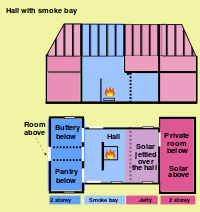

The rooms on the ground floor of the private space, were often known as parlours while the upper floor provided rooms called solars. The upper rooms would be reached in the simplest buildings by means of a ladder or steep companionway.[lower-alpha 2][8] The solars often stretched beyond the outer wall of the ground floor rooms, jettying out at one end or else at both ends of the building. As the hall itself had no upper floor within it, its outer walls always stood straight, without jettying.[9]

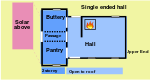

- Single ended hall plans

Here a two-story wing is attached to one end of the hall. This can project beyond one side wall or both side walls of the hall, or sometimes just the upper story is jettied beyond the side wall. There were multiple solutions as to where the staircase was placed.[10]

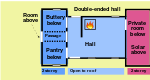

- Double ended hall plans

The open hall is flanked by two two-story extension. Together they can give the appearance of an H-shape as at Little Moreton Hall or a U-shape as is found in Cambridgeshire. The Clothiers' houses of the West Riding of Yorkshire were built with elaborate gables[10]

- Wealden houses

Wealden houses are a specific form of the double ended hall plan. They are built of timber and at ground floor level the wings do not project being the width of the hall in length. The upper-storeys of the wings are jettied out, and the roof-line follows this projection.[10]

Later alterations

.jpg)

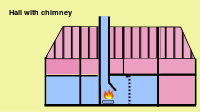

The vast majority of those hall houses which have survived have changed significantly over the centuries. In almost all cases the open hearth of the hall house was abandoned during the early modern period and a chimney built which reached from the new hearth to above the roof. This was created in the vicinity of the cross passage, and sometimes this added chimney actually blocked the cross passage.[11] Once the clearance within the hall was no longer needed for smoke from the central hearth, the hall itself would often be divided, with a floor being inserted which connected all the upper rooms.

Timber framed hall houses often had the infilling between their structural timbers replaced several times. While the timbers themselves were the strongest part of the building, it is unusual for all to have survived without replacement. In many cases whole outer walls have been replaced with solid brick or with solid stone. Usually a thatched roof was turned into one of slates or tiles.

A successful building was likely to be extended to follow the fashion or to add needed additional accommodation, and it is even possible for a medieval hall house to be hidden within an apparently much later building and to go unrecognized for what it is, until alteration or demolition reveals the tell-tale smoke-blackened roof timbers of the original open hall.[12]

Materials

The construction techniques used in vernacular architecture always were dependent on the materials available, and hall houses were no exceptions. Stone, flint, cobble, brick and earth when available could be used to build walls that would support the mass on the roof structure. Alternatively, a cruck or a box frame structure of timber was built and this could be infilled with cob or be panelled with timber, tiles, or wattle and daub. [13] Depending on the local tradition and availability thatched and stone roofs were used. A thirteenth century example of a stone roofed hall-house survives in a good state of preservation at Aydon Hall in Northumberland.[14]

Hearths, smoke bays and fireplaces

In a two-wing hall house, with the hall open to the roof, smoke accumulated in the roofspace before exiting through louvres or raised tiles. Placing the hearth at the lower end of the hall was deliberate because combustion could be controlled by varying the through draught between the two doors.[11]

The next phase was to jetty out the first floor private accommodation into the open hall creating a half floor. The smoke rose into the remaining space into a smoke bay. The house benefitted from the extra space created, and the extended chambers benefitted from the extra heat. The use of smoke hoods enabled the smoke bays to be compressed further. In Surrey smoke bays were introduced in the early 16th century while in the North it was later, smoke hoods being introduced in the late 17th century.[11]

A brick built fireplace, chimney breast, flue and chimney stack gave more efficient combustion. This allowed the whole of the hall to be floored, then the stack could contain an extra flue to provide a fire on the upper floor. Fireplaces and chimney stacks could be fitted into existing buildings against the passage, or against the side walls or even at the upper end of the hall. It was only at the end of the 18th century that this innovation reached the north.[11]

The design and total function of the chimney depended on the size of the house or cottage and its location. English fires never became like the continental tiled cocklestove or the North American metal stove.[15] In the earliest houses combustion of wood was helped by increasing the airflow by placing the logs on iron firedogs. In smaller houses the fire was used for cooking. Andirons provided a rack for spit roasting, and trivets for pots. Later an iron or stone fireback reflected the heat forward and controlled the unwelcome side draughts. Unsurprisingly the hearth migrated to a central wall and became enclosed at the sides. The earliest firehoods directed the smoke away from the low underthatch to the apex of the roof. They were constructed in wicker which was then lime-plastered to render them fire-proof.[16]

Inglenook fireplaces were a development. One side of the inglenook was a transverse wall, one of the others was the exterior wall which was pierced with a little 'fire window' that gave light. To the other side was an low partition wall with a settle to provide seating. A beam or bressumer at head height finished off the open end. The hearth stone extended across this whole area, and it was topped with a firehood. It became a room within a room. It was particular suited to burning logs and peat. In the Weald of Kent and Sussex, which were early iron smelting regions the back wall was protected by an iron fireback.[17]

The fireplace is a three-sided incombustible box containing a grate that allows an updraught and a controlled flue. It is most suited to burning sea-cole. Sea-cole or coal as it is now called was quarried from outcrops around England and transported to London as early as 1253.[18] [19] In larger houses, fireplaces and chimneys were first used as supplementary heating in the parlour, before eventually suppressing the open hearth. In smaller hall houses, where heat efficiency and cooking were the prime concern, fireplaces became the principal source of heat earlier. The design of the coal grate was important and the open fire became more sophisticated and enclosed leading in later centuries to the coal burning kitchen range with its hob, oven and water boiler, and the Triplex type kitchen range with a back boiler and the 1922 AGA cooker.[20]

Examples

Unaltered hall houses are almost unknown. A large number of former hall-houses do still exist and many are cared for by the National Trust, English Heritage, local authorities and private owners. Wealden hall houses can be found in the weald of Kent and Sussex where the combination of good quality hard wood and wealthy yeoman farmers and iron founders prevailed in the 14th to 16th centuries. In Crawley today the Ancient Priors, the Old Punch Bowl and the Tree House are well documented as is Alfriston Clergy House in Polegate, East Sussex, which was the first house to be acquired by the National Trust. The Weald and Downland Open Air Museum has a collection of rescued house which have been extensively researched prior to their reconstruction. Elsewhere such as in Cheshire and Suffolk historic timber framed house often contain the remnants of hall houses. Hole Cottage in Kent near Cowden (operated by Landmark Trust) has an intact private dwelling wing of a Wealden hall house.

Ancient Priors

.jpg)

The Ancient Priors is a medieval timber-framed hall house on the High Street in Crawley. It was built in approximately 1450, partly replacing an older (probably 14th-century) structure—although part of this survives behind the present street frontage.[21] It has been expanded, altered and renovated many times since, and fell into such disrepair by the 1930s that demolition was considered. It has since been refurbished and is now a restaurant, although it has been put to various uses during its existence. English Heritage has listed the building at Grade II* for its architectural and historical importance, and it has been described "the finest timber-framed house between London and Brighton".[22][23] Crawley's development as a permanent settlement dates from the early 13th century, when a charter was granted for a market to be held;[24] a church was founded by 1267.[25] The area, on the edge of the High Weald. Some sources assert that a building stood on the site of the Ancient Priors by this time, claiming that it was built between 1150[26] and 1250[27] and was used as a chantry-house.[22][27][28] Extensive archaeological investigation in the 1990s determined that although the possibility of an older building on the site could not be ruled out,[29] the oldest part of the present structure is 14th-century and the main part (fronting the east side of the High Street) dates from about 1450 and incorporates no older fabric.[21] Burgage plots—medieval land divisions with houses or other buildings which were rented from the Lord of the Manor—were particularly clearly defined on the east side of the High Street; the buildings within them usually faced the High Street, but plots were sometimes subdivided.[30] This is believed to have happened at the site of the Ancient Priors, where the main (15th-century) part of the building faces west on to the High Street, and the older section faces south and is hidden from view.[21][30] The building was originally used as a dwelling house, and the accompanying burgage plot was used for small-scale agriculture.[21][31] The first confirmed owners were a family of colliers, who acquired it in 1608. It passed through many owners throughout the 17th century, some of whom rented the building to others; furthermore, in many cases the two parts of the building were occupied by different families or tenants.[31] By 1668, when it was owned by a resident of Worth, the whole building had become an inn. Known at first as The Whyte Harte, its spelling was later standardised to The White Hart. Around this time, the entire messuage consisted of the inn itself, some barns, an orchard and a garden.[31] In the early 18th century, the prominent local ironmaster Leonard Gale—holder of much property in the Crawley area—owned the building, and is believed to have lived there.[27][32] By 1753, when the Brett family (who had held the property for 26 years) sold the messuage for £473 (£72,600 as of 2020),[33] it also had stables, and covered about 2 acres (0.81 ha).[34]

In Cheshire Willot Hall, Bramall Hall and Little Moreton Hall all noted for their black and white half timbered appearance, are extended from an initial hall-house. And in Merseyside Speke Hall and Rufford Old Hall similarly benefited from agricultural prosperity.

Rufford Old Hall

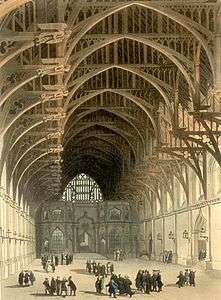

Rufford Old Hall is a National Trust property and Grade I listed building,[35] in Rufford, Lancashire, England. Only the great hall, built around 1530 for Sir Robert Hesketh, survives from the original building but it indicates the wealth and position of the family.[36] Until 1936, Rufford Old Hall was in the continuous ownership of the Hesketh family who were lords of the manor of Rufford from the 15th century. The Heskeths moved to Rufford New Hall in 1798. In 1936 Rufford Old Hall, with its collection of arms and armour and 17th century oak furniture, was donated to the National Trust by Thomas Fermor-Hesketh, 1st Baron Hesketh.

The timber-framed hall house with great hall, in a late medieval pattern which continued in use in Tudor times, was built for Sir Robert Hesketh in about 1530. The hall, which formed the south wing of the present building, is substantially as built, 46.5 feet (14.2 m) long and 22 feet (6.7 m) wide, with the timbers sitting on a low stone wall. The hall has a flagged floor.[37] It has a stone chimney, five bays, and a hammerbeam roof. The five hammerbeams each terminate, at both ends, in a carved wooden angel.[38] The hall is overlooked by a quatrefoil squint in an arched doorway in the second-floor drawing room.[36] In 1661 a Jacobean style rustic brick wing was built at right angles to the great hall which contrasts with the medieval black and white timbering. This wing was built from small two-inch bricks similar to Bank Hall, and Carr House and St Michael's Church in Much Hoole.[39]

Ufford Hall

Ufford Hall is a Grade II* listed manor house in Fressingfield, Suffolk, England, dating back to the thirteenth century. Fressingfield is 12 miles east of Diss, Norfolk. The timber-framed manor house with rosy ochre coloured plaster walls and dark tiled roof,[40] incorporates the medieval core of an earlier open-hall house. At least twenty raised-aisled houses have been identified in the area, "forming a characteristic group, rarely found elsewhere in England".[41] The Hall has attracted the attention of architectural historians, such as Pevsner[42] and Sandon,[40] and has been described as the “ultimate development (…) of the early hall house.”[43] Its most noteworthy features include: cross-beamed ceiling in the parlour which has not been disturbed since the late fifteenth century or early sixteenth century; striking original sixteenth-century mullioned and transomed windows; back-to-back stuccoed fireplaces on both floors and chimney stacks of Tudor origin; fine Jacobean dog-leg staircase with turned balusters and newel posts with ball finials. The latter is the last major addition to the house, which remains largely unaltered from the original.

Plas Uchaf

Plas Uchaf (English: Upper Hall) is a 15th-century cruck-and-aisle-truss hall house, that lies within the stone building belt 1.5 miles (2.4 km) south-west of Corwen, Denbighshire, Wales and 1 mile (1.6 km) north of Cynwyd.[44] The house consists of a long rectangle divided by a cross passage. The west end is a large hall some 25 feet (7.6 m) high.[45] The east end consists of smaller rooms on two floors. The roof structure is substantial, of paired cruck beams with additional horizontal, vertical and diagonal bracing.[46] It features an aisle truss, a form normally only found in much larger buildings such as barns and churches. This suggests the use of English craftsmen[45] and is an indication of the status of the original inhabitants.[47] The walls are of stone rubble[45] but were originally half-timbered.[48] The original construction was thought to date from the late 14th or early 15th century,[45] but part of the structure has been dated to 1435 by tree-ring dating.[48] In the 16th century the hall was divided horizontally by the addition of an inserted floor supported by moulded cross beams.[45] The house was listed as a house of the gentry as late as 1707[49] but was later split into two or three labourers' cottages.[45][50]

West country

Old Shute House (known as Shute Barton between about 1789 and the 20th century), located at Shute, near Colyton, Axminster, Devon, is one of the more important extant non-fortified manor houses of the Middle Ages. It was built about 1380 as a hall house and was greatly expanded in the late 16th century and partly demolished in 1785. The original 14th-century house survives, although much altered.[51] Whitestaunton Manor in south Somerset was built in the 15th century as a hall house and has been designated as a Grade I listed building.[52] It consists of an east-west range with two wings which were added later.[53]

Northumberland

Aydon Hall and Featherstone Castle in Northumberland were stone-built hall houses. The owners applied for permission to crenellate to protect the buildings from the marauding Scottish insurgents. The original halls became part of substantial castles- which later, with the Act of Union became grand country houses. Harewood Castle is a 12th-century stone hall house and courtyard fortress, located on the Harewood Estate, Harewood, in Leeds, West Yorkshire.

See also

- Hall (concept)

- Great hall

- Hall and parlor house

- Low German hall house

- Middle German house

- Wealden hall house

- Vernacular architecture

References

- Notes

- Ronald Brunskill [3] describes vernacular architecture as:

...a building designed by an amateur without any training in design; the individual will have been guided by a series of conventions built up in his locality, paying little attention to what may be fashionable. The function of the building would be the dominant factor, aesthetic considerations, though present to some small degree, being quite minimal. Local materials would be used as a matter of course, other materials being chosen and imported quite exceptionally.

- A companionway was often fitted into a shallow cupboard set into one end the partition separating the private rooms from the hall. It would be a straight flight of treads set into a box frame, differing from a ladder in that it was fixed in place. An alternative was the spiral stair case where solid timber steps would span between the timber wall and a mast like newell. This would twist 180 deg from floor to floor

- Citations

- John E. Crowley, The Invention of Comfort: Sensibilities and Design in Early Modern Britain and Early America (Baltimore, Maryland: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2003), p. 8

- Brunskill 2004, p. 40.

- Brunskill 2000, pp. 27, 28.

- Brunskill 2004, p. 124.

- Brunskill 2004, pp. 112, 113.

- Brunskill 2000, pp. 122, 123.

- Brunskill 2000, p. 104, 105.

- Brunskill 2000, pp. 124,125.

- Brunskill 2000a, p. 54.

- Brunskill 2000, pp. 104,105.

- Brunskill 2000, pp. 122,123.

- David J. Swindells, Restoring period timber-framed houses (1987), p. 165

- Brunskill 2000, p. 36.

- W. Douglas Simpson, Exploring Castles (London: Routledge and Kegan Paul, 1957), p. 51

- Brunskill 2004, p. 116.

- Brunskill 2004, pp. 112,113.

- Brunskill 2004, pp. 112,113,115.

- "coal, 5a". Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. 1 December 2010.

- Brunskill 2004, p. 115.

- Brunskill 2004, pp. 115,116.

- Hygate 1994, p. 3.

- "Minter's, The High Street, Crawley". West Sussex Gazette newspaper. West Sussex County Times Ltd (now part of Johnston Press PLC). 14 September 1978.

- "The Ancient Priors at Crawley". West Sussex Gazette and South of England Advertiser newspaper. West Sussex County Times Ltd (now part of Johnston Press PLC). 9 June 1960.

- Goepel 1980, p. 4.

- Gwynne 1990, p. 40.

- Volke 1989, p. 53.

- Goldsmith 1987, §29.

- Gwynne 1990, p. 58.

- Hygate 1994, p. 1.

- Harris, Roland B. (December 2008). "Crawley Historic Character Assessment Report" (PDF). Sussex Extensive Urban Survey (EUS). English Heritage in association with Crawley Borough Council. p. 26. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-08. Retrieved 2009-10-14.

- Hygate 1994, p. 9.

- Bastable 1983, §33.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Hygate 1994, p. 12.

- Listed Buildings in West Lancashire Archived 2011-06-06 at the Wayback Machine, West Lancashire District Council

- Dean, R., 2007, Rufford Old Hall, The National Trust, ISBN 978-1-84359-285-3

- Farrer, William; Brownbill, J, eds. (1911). Rufford. A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6. British History Online. pp. 119–128. Retrieved 2011-03-17.

- "Rufford Old Hall". Listed Buildings Online. Retrieved 2011-03-16. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Farrer, William; Brownbill, J, eds. (1911). Bretherton. A History of the County of Lancaster: Volume 6. British History Online. pp. 102–108. Retrieved 2011-09-21.

- Sandon, Eric (1977), Suffolk Houses, A Study of Domestic Architecture, Woodbridge, Suffolk: Baron Publishing, 1977, p. 175

- Emery, Anthony (2000), Greater Medieval Houses of England and Wales, Vol. II, Cambridge University Press, p. 24

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1961), The Buildings of England: Suffolk, London: Penguin Books, p. 203

- Cook, Olive & Edwin Smith (1983), The English House through Seven Centuries, Overlook Press, p. 69

- Ayres, James (1981). The Shell Book of The Home In Britain. London: Faber & Faber. p. 12. ISBN 0-571-11625-6.

Despite its relatively small size this house was of palatial significance in relation to its time and place

- Monroe, L (1933). "Plas Ucha, Llangar, Merioneth". Arch Camb. pp. 81–87.

- Smith, Peter; Lloyd, Ffrangcon (1965). "Plas-Ucha, Llangar, Corwen". Transactions of the Ancient Monuments Society 1964. 12. London: The Ancient Monuments Society. pp. 97–112.

- Smith, Peter (1988). "Aisle-truss and hammer-beam roofed houses". Houses of the Welsh Countryside - A study in historical geography (Second enlarged ed.). London: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. pp. 94–95.

- "Plas Uchaf; Plas Ucha, Cynwyd, Cynwyd". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 2010-08-08.

- Cited by Smith/LLoyd as "Edward Llwyd, Parochilia (ed. R. H. Morris), II, p. 56"

- "1871 census Llangar". GENUKI - UK & Ireland Genealogy. Retrieved 2010-08-11.

- Cooper, Nicholas; Mannez, Pru; Blaylock, Stuart, Shute Barton, Devon: Historic Building Analysis and Archaeological Survey 2008, Exeter Archaeology Report no. 08.80, produced for the National Trust

- Historic England. "Whitestaunton Manor (1250783)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 2009-07-07.

- Historic England. "Whitestaunton Manor (190386)". PastScape. Retrieved 16 December 2012.

- Bibliography

- Brunskill, R.W. (2000). Vernacular Architecture: An illustrated Handbook. London: Faber & Faber. ISBN -0-571-19503-2.

- Bastable, Roger (1983). Crawley: A Pictorial History. Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 0-85033-503-5.

- Brunskill, Ronald (2000a). 'Rural houses and cottages; Wealden and other open-hall houses' in Houses and Cottages of Britain: Origins and Development of Traditional Buildings. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-575-07122-3.

- Brunskill, R.W. (2004). Traditional Buildings of Britain: an introduction to Vernacular Architecture. London: Orion Books. ISBN 0-304-36676-5.

- Goepel, J. (1980). Development of Crawley. Crawley: Crawley Borough Council.

- Goldsmith, Michael (1987). Crawley and District in Old Picture Postcards. Zaltbommel: European Library. ISBN 90-288-4525-9.

- Gwynne, Peter (1990). A History of Crawley (1st ed.). Chichester: Phillimore & Co. ISBN 0-85033-718-6.

- Hygate, Nâdine (1994). 49, High Street, Crawley. Horsham: Performance Publications.

- Volke, Gordon, ed. (1989). Historic Buildings of West Sussex. Partridge Green: Ravette Publishing. ISBN 1-85304-199-8.