Terraced houses in the United Kingdom

Terraced houses have been popular in the United Kingdom, particularly England and Wales, since the 17th century. They were originally built as desirable properties, such as the townhouses for the nobility around Regent's Park in central London, and the Georgian architecture in Bath.

The design became a popular way to provide high-density accommodation for the working class in the 19th century, when terraced houses were built extensively in urban areas throughout Victorian Britain. Though numerous terraces have been cleared and demolished, many remain and have regained popularity in the 21st century.

Definition

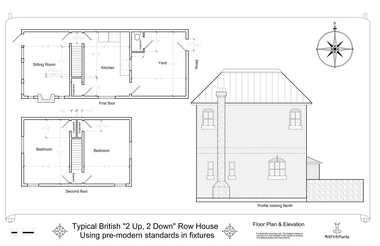

Terraced houses, as defined by various bye-laws established in the 19th century, particularly the Public Health Act 1875, are distinguished by properties connecting directly to each other in a row, sharing a party wall. A house may be several storeys high, one or two rooms deep, and optionally contain a basement and attic.[1] In this configuration, a terraced house may be known as a two-up two-down, having a ground and first floor with two rooms on each.[2] Most terraced houses have a duo pitch gable roof.[3]

For a typical two-up two-down house, the front room has historically been the parlour, or reception room, where guests would be entertained, while the rear would act as a living room and private area.[4] Many terraced houses are extended by a back projection, which may or may not be the same height as the main build. A terraced house has windows at both the front and the back of the house; if a house connects directly to a property at the rear, it is a back to back house.[1] 19th century terraced houses, especially those designed for working-class families, did not typically have a bathroom or toilet with a modern drainage system; instead these would have a privy using ash to deodorise human waste.[5]

Origin

Terraced houses were introduced to London from Italy in the 1630s.[6] Covent Garden was laid out to resemble the Palazzo Thiene in Venice.[7] Terraces first became popular in England when Nicholas Barbon began rebuilding London after the Great Fire in 1666.[8] The terrace was designed to hold family and servants together in one place, as opposed to separate servant quarters, and came to be regarded as a "higher form of life".[6] They became a trademark of Georgian architecture in Britain,[9] including Grosvenor Square, London, in 1727 and Queen's Square, Bath, in 1729.[10] The parlour became the largest room in the house, and the area where the aristocracy would entertain and impress their guests.[11]

17th and 18th-century terraced houses did not use as sophisticated construction methods compared to later. Building materials were supplied locally, using stone where possible (such as Bath stone in the eponymous city), otherwise firing brick from clay. The house was divided into small rooms partly for structural reasons, and partly because it was more economical to supply timber in shorter lengths.[12] The London Building Act of 1774 made it a legal requirement for all terraced houses there to have a minimum wall thickness and a party wall extending above the roofline to help prevent fire spreading along the terrace along with other specified basic building requirements. However, these requirements did not extend elsewhere, and towns had varying requirements until the mid-19th century.[6]

19th century

Terraced houses were still considered desirable architecture at the start of the 19th century. The architect John Nash included terraced houses when designing Regent's Park in 1811, as it would allow individual tenants to feel as if they owned their own mansion.[13]

The terraced house reached mass popularity in the mid-19th century as a result of increased migration to urban areas. Between 1841 and 1851, towns in England grew over 25% in size, at which point over half the population lived in urban areas; this increased further to nearly 80% by 1911. Terraced houses became an economical solution to fit large numbers of people into a relatively constricted area.[14] Many terraced houses were built in the South Wales Valleys in the mid to late 19th century owing to the large-scale expansion of coal mining there. In the Rhondda, the population increased from 4,000 in 1861 to 163,000 in 1891. Because of the imposing local geography, containing narrow river valleys surrounded by mountains, terraced houses were the most economic means of providing sufficient accommodation for workers and their families.[15]

Nationwide legislation for terraced housing began to be introduced during the Victorian era. The 1858 Local Government Act stated that a street containing terraced houses had to be at least 36 feet (11 m) wide with houses having a minimum open area at the rear of 150 square feet (14 m2), and specified the distance between properties should not be less than the height of each. Other building codes inherited from various local councils defined a minimum set of requirements for drainage, lighting and ventilation. The various acts led to a uniform design of terraced houses that was replicated in streets throughout the country.[6]

This design was still basic, however; for example, in 1906, only 750 houses out of 10,000 in Rochdale had an indoor WC.[16] Sanitation was handled, imperfectly, by outhouses (privies) shared between several dwellings.[17] These were originally various forms of "earth closet" (such as the Rochdale system of municipal collection) until legislation forced their conversion to "water closet" (flush toilet).

Terraced houses were as popular in working-class Northern Ireland as in Britain. The Bogside in Derry is composed mainly of traditional Victorian terraces and their overcrowding in the mid-20th century was a key trigger for the Troubles.[18]

Though many working-class people lived in terraces, they were also popular with middle classes in some areas, particularly the North of England. In 1914, despite the introduction of newer housing, terraces still catered for 71% of the population in Leeds. In some areas, these terraces contained 70–80 houses per acre.[4] Houses were generally allowed to be used for commercial purposes, with many front rooms being converted to a shop front and giving rise to the corner shop.[11] By the 1890s, larger terraces designed for lower-middle-class families were being built. These contained eight or nine rooms each and included upstairs bathrooms and indoor toilets.[19]

20th century

Terraced houses began to be perceived as obsolete following World War I and the rise of the suburban semi-detached house.[20] After new legislation for suburban housing was introduced in 1919, Victorian terraces became associated with overcrowding and slums, and were avoided.[21] Terraced houses continued to be used by the working class in the 1920s and 30s, though Tudor Walters state owned houses, such as those in Becontree, became another option.[22] Developers built "short terraces" of only a few contiguous houses, to resemble semi-detached housing.[23] Back to back housing, popular for 19th century low-class homes throughout Northern England, was outlawed in most towns by 1909, finally becoming obsolete in Leeds by 1937.[1] Although the worst slums deemed "unfit for human habitation" were demolished, progress on removing terraced estates was slow. The criteria of what constituted a "slum" gradually rose during the early 20th century, such that by the 1950s it was applied to houses that had been previously considered perfectly acceptable.[21] The Housing Act 1957 set a new mandatory set of requirements for houses, including running hot water, inside or "readily accessible" toilet, and artificial lighting and heating in all rooms, which required modernisation of Victorian terraces.[24]

Since the 1950s, successive governments have looked unfavourably on terraced houses, believing them to be outdated and attempting to clear the worst slums.[25] Between 1960 and 1967, around half a million houses deemed unfit were demolished.[26] Tower blocks began to replace terraces in working class areas, though public opinion began to change against them following incidents such as the collapse of the Ronan Point tower block in 1968. By the 1970s, traditional urban terraces were being upgraded by fitting modern bathroom and heating systems, and began to become popular again.[27] Residents in Leeds began to protest against the blanket demolition of back to back houses, saying they were perfectly acceptable accommodation for the elderly and low-income households.[28]

21st century

In 2002, the Labour government introduced the Housing Market Renewal Initiative scheme, which would see many terraced houses demolished and replaced with modern homes, in order to attract middle-class people into area and improve its quality. The scheme was controversial and unsuccessful, as many of the terraces that had survived the 1960s cull were well-built and maintained, and has led to many derelict terraces in urban areas.[25] In 2012, 400 homes in Liverpool were planned to be demolished; a small number were saved, including the birthplace of the Beatles' Ringo Starr in the Welsh Streets.[29]

Despite their association with the working class and Victorian Britain, terraced houses remain popular. In 2007, a report by Halifax Estate Agents showed prices of terraces had increased by 239% over the past ten years, with an average price of £125,058.[8] By 2013, the average price for a terraced house had exceeded £200,000.[30] Conversely, Wales Online reported in 2011 that a terraced house in Maerdy, Rhondda, was one of the cheapest on the market at £7,000.[31] In 2015, the television show DIY SOS filmed a group project to rebuild a street of derelict terraced houses in Newton Heath, Manchester, as homes for retired war veterans.[32] Because few terraced houses are listed, they are easier to convert as planning permission is either unnecessary or simpler, with English Heritage describing them as being 60% cheaper to maintain on average. By 2011, a fifth of new houses built in Britain were terraced, and recreations of classic Georgian terraces have been built, such as at Richmond Lock.[10]

References

Citations

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 62.

- "two-up two-down". Cambridge dictionaries online. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- Friedman 2012, p. 53.

- Scott 2013, p. 19.

- Eveleigh 2008, p. 3.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 61.

- Gorst 2003, p. 3.

- Moye, Catherine (12 April 2007). "The rise and fall of a British favourite". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- Gorst 2003, p. 175.

- Norwood, Graham (22 October 2011). "Life on the terraces: The classic two-up two-down is back in demand". The Independent. Retrieved 21 November 2015.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 63.

- Gorst 2003, p. 4.

- Morris 2013, p. 268.

- Eveleigh 2008, p. 1.

- Nash, Davies & Thomas 1995, p. 3.

- Meacham, Standish (Spring 1984). "Reviewed work: The Last Country Houses, Clive Aslet; the English Terraced House, Stefan Muthesius". Victorian Studies. 27 (3): 382–384. JSTOR 3826862.

- "Victorian and Edwardian Services (houses) 1850–1914". University of the West of England. Retrieved 7 May 2017.

- Ireland. Lonely Planet. 2008. p. 644. ISBN 978-1-741-04696-0.

- Eveleigh 2008, p. 5.

- Scott 2013, p. 233.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 66.

- Scott 2013, p. 235.

- Scott 2013, p. 72.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 70.

- Hatherley, Owen (27 March 2013). "Liverpool's rotting, shocking 'housing renewal': how did it come to this?". The Guardian. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 71.

- Scott 2013, p. 242.

- Ravetz & Turkington 2013, p. 73.

- "Ringo Starr's birthplace on Madryn Street, Liverpool, saved". 14 June 2012. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "UK House prices : April to June 2013". BBC News. Retrieved 23 November 2015.

- "Could this Rhondda terraced house be the cheapest in Wales? (At £7,000 it's got to be close)". Wales Online. 21 March 2013. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

- "DIY SOS veterans' village completed after volunteers work over the weekend". Manchester Evening News. 28 September 2015. Retrieved 20 November 2015.

Sources

- Eveleigh, David (2008). "Victorian & Edwardian Services (Houses) 1850–1914". University of West England, Bristol. Retrieved 20 November 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Friedman, Avi (2012). Town and Terraced Housing: For Affordability and Sustainability. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-136-63843-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gorst, Thom (2003). The Buildings Around Us. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-135-82328-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Morris, A.E.J. (2013). History of Urban Form Before the Industrial Revolution. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-88514-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nash, Gerallt; Davies, Trefor Alun; Thomas, Beth (1995). Workmen's Halls and Institutes: Oakdale Workmen's Institute. National Museum of Wales. ISBN 978-0-720-00430-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Ravetz, Alison; Turkington, R (2013). The Place of Home: English Domestic Environments, 1914–2000. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-15846-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Scott, Peter (2013). The Making of the Modern British Home: The Suburban Semi and Family Life Between the Wars. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-67720-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Terraced houses in the United Kingdom. |

- Search for Spinners' End A description of working class terraced house evolution used to postulate on a fictional location.