HMS Pearl (1762)

HMS Pearl was a 32-gun fifth-rate frigate of the Niger-class in the Royal Navy. Launched at Chatham Dockyard in 1762, she served in British North America until January 1773, when she sailed to England for repairs. Returning to North America in March 1776, to fight in the American Revolutionary War, Pearl escorted the transports which landed troops in Kip's Bay that September. Much of the following year was spent on the Delaware River where she took part in the Battle of Red Bank in October. Towards the end of 1777, Pearl joined Vice-Admiral Richard Howe's fleet in Narragansett Bay and was still there when the French fleet arrived and began an attack on British positions. Both fleets were forced to retire due to bad weather and the action was inconclusive. Pearl was then dispatched to keep an eye on the French fleet, which had been driven into Boston.

HMS Pearl battles the Santa Monica off the Azores in 1779 | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Pearl |

| Ordered: | 24 March 1761 |

| Cost: | £16,573.5.4d |

| Laid down: | 6 May 1761 |

| Launched: | 27 March 1762 |

| Completed: | 14 May 1762 |

| Commissioned: | April 1762 |

| Renamed: | Protheé (March 1825) |

| Fate: | Sold 1832 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | Niger-class fifth-rate frigate |

| Tons burthen: | 683 16⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: |

|

| Beam: | 35 feet 3 inches (10.7 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 12 feet 0 inches (3.7 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Sail plan: | Fully Rigged Ship |

| Complement: | 220 |

| Armament: | |

Pearl was part of the British fleet that captured the island of St Lucia in December 1778 and was chosen to carry news of the victory to England, capturing the 28-gun Spanish frigate Santa Monica off the Azores on her return journey. Pearl joined Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot's squadron in July 1780, capturing the 28-gun French frigate Esperance while stationed off Bermuda in September and, in the following March, took part in the first battle of Virginia Capes, where she had responsibility for relaying signals. At the end of the war in 1782, Pearl returned to England where she underwent extensive repairs and did not serve again until 1786, when she was recommissioned for the Mediterranean.

Taken out of service in 1792, Pearl was recalled in February 1793, when hostilities resumed between Britain and France. On her return to America, she narrowly escaped capture by a French squadron anchored between the Îles de Los and put into Sierra Leone for repairs following the engagement. In 1799, Pearl joined George Elphinstone's fleet in the Mediterranean where she took part in the Battle of Alexandria in 1801. In 1802, she sailed to Portsmouth where she served as a slop ship and then a receiving ship. She was renamed Protheé in March 1825 and eventually sold in 1832.

Construction and armament

Pearl was a 32-gun, Niger-class frigate built to Thomas Slade's design and ordered on 24 March 1761.[1] Her keel was laid down at Chatham Dockyard on 6 May.[2]

When launched on 27 March 1762, Pearl was 125 feet 0 1⁄2 inch (38.1 m) along the gun deck, 103 feet 4 3⁄8 inches (31.5 m) at the keel, had a beam of 35 feet 3 inches (10.7 m) and a depth in the hold of 12 feet 0 inches (3.7 m).[2] She was 683 16⁄94 tons burthen and by the time she had been completed, on 14 May 1762, she had cost The Admiralty £16,573.5.4d.[2]

Niger-class frigates were fifth-rates, carrying a main battery of twenty-six 12-pounder (5.4 kg) guns on the upper deck, four 6-pounder (2.7 kg) guns on the quarterdeck and two on the forecastle. When fully manned, they carried a complement of 220.[3]

Service

Pearl was first commissioned in April 1762, under Captain Joseph Deane, who took her to The Downs, to be fitted-out. In March 1763 she was recommissioned under Captain Charles Saxton and on 22 May 1764, she left for Newfoundland in British North America.[2] Pearl served there under captains Patrick Drummond and, subsequently, John Elphinston, until she paid off in December 1768.[4] She was recommissioned the following month under John Leveson-Gower, then Sir Basil Keith in November.[5]

Between April 1770 and January 1773, Pearl spent time on and off the Newfoundland station, first under John Ruthven then James Bremer. She then sailed for Portsmouth where she underwent repairs, then a refit, at a total cost of £9,008.15.11d. The combined works took until February 1776.[5] John O'Hara, who had assumed command in November 1775, was replaced by Thomas Wilkinson in March 1776, shortly after completion.[5]

American Revolutionary War

Wilkinson returned Pearl to North America in April to fight in the revolutionary war, bringing a convoy of troopships from Ireland to Quebec, with HMS Carysfort.[5][6] She took part in the landings at Kip's Bay in September, escorting transports along the Hudson River before creating a diversion in the North River.[7][8] On the evening of 13 September, six troopships, HMS Roebuck, Phoenix, Orpheus and Carysfort, moved up the East River and anchored in Bushwick Creek, opposite Kip's Bay.[9] To draw attention away from the intended landing site, at the same time, Pearl, HMS Renown and Repulse were sent up the North River. The squadron passed the enemy's batteries on 15 September but the fire received did so little damage, the British ships continued without bothering to return it.[10] They eventually anchored at Bloomingdale, 6 nautical miles (11 kilometres) above New York.[8]

Towards the end of the year, Pearl joined a small squadron under Andrew Snape Hamond on a cruise along the coast to South Carolina and on 20 December, captured the 16-gun sloop USS Lexington.[5][11] A strong gale prevented the removal of prisoners and the allocation of an adequate prize crew, and with only eight British sailors on board, she was retaken that night.[11] Sometime later, Pearl detained a French vessel, carrying arms and ammunition. Wilkinson saw this as proof that the French were aiding the Americans but as there had been no formal declaration of war at that point, he was obliged to let them go.[11]

From South Carolina Pearl sailed to Antigua where she arrived on 27 January 1777 to await careening and refitting.[12][11][13] While this was being carried out, on 13 February, Wilkinson died from disease and was replaced by George Elphinstone.[14][15] Work was completed mid-March, after long delays caused by a shortage of skilled labour, and Pearl was returned to the American coast, leaving English Harbour in the company of HMS Roebuck, Perseus and Camilla on 18 March.[14][15][12] Despite the time spent in port, Pearl managed more than a dozen captures between January and May 1777, including Batchelor on 21 March (which was suspected of piracy on account of its armament) and a whaleboat from Lewes on 29 May that was thought to be spying.[16][17] Another change in command occurred in 1777 when John Linzee was appointed as captain[5][Note 1] and on 6 July 1777, boats from Pearl and Camilla captured and burned the Continental schooner Mosquito in a cutting out expedition.[5] The American vessel of six guns and four swivels, was moored in a tributary of the Delaware River when, at 03:00, the British sailors boarded without opposition. The only two people guarding her, the master and the gunner, were taken off and she was set alight.[18]

Pearl was anchored off Bombay Hook on 21 July. At 15:00, a fleet of twelve Continental Navy vessels, under command of Charles Alexander in the frigate, Delaware, came in sight. A signal gun was fired to warn her tender, which was ashore collecting supplies, then Pearl weighed and sailed off but ran aground on Cross Ledge. The tender was captured along with a fortnight's worth of provisions but Pearl managed to get free and escape downriver.[19] At 11:00 the following morning she spotted Camilla some 6 nmi (11 km) away. Pearl requested she join her and the two ships anchored to await the enemy fleet.[20] On the morning of 23 July, an American vessel came under a flag of truce but by this time a third British ship, HMS Liverpool, had sailed into view. At 06:00 the next day, the American fleet arrived and made a second attempt to discuss terms but were dismissed. The three British frigates cleared for action, the Americans scattered and were pursued up the river but never caught; the British losing sight of their quarry and giving up the chase the next day.[21]

Assault on Philadelphia

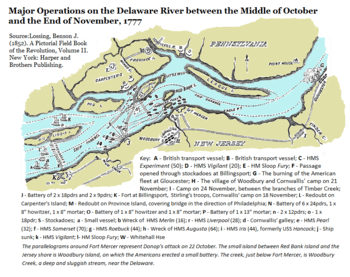

When American forces were defeated at the Battle of Brandywine and retreated to Philadelphia that September, Pearl was part of a squadron tasked with opening up the Delaware River which had been heavily protected with redoubts and sunken obstructions to prevent its navigation. Led by Richard Howe in Roebuck, the small force worked its way upstream to Billingsport, where a large earthworks and gun battery protected a channel, blocked with a submerged cheval de frise.[22][23] The impediment comprised large wooden frames, filled with stones and fronting iron-tipped spears. Stationed along the river were floating batteries and gunboats, and 3 miles (4.8 km) further upstream, another set of obstacles had been sunk between Fort Mifflin and Fort Mercer.[24] On 22 September, Pearl, Roebuck, Liverpool, HMS Augusta, forced a passage in order to support an attack on Red Bank by British troops.[25] Although joined later by HMS Isis and the 16-gun sloop Merlin, the British vessels were subjected to heavy fire when they engaged the American flotilla and batteries. Augusta ran aground and caught fire, and the sloop, Merlin, blew up; Pearl and the remaining force broke off the attack and returned to Billingsport.[26][27]

British troops entered Philadelphia on 26 September but a supply route was needed and control of the river was therefore crucial. In November, Province Island was captured and Howe began erecting batteries. A hulk was converted to a floating gun platform and with the assistance of Pearl, Roebuck and Liverpool, a six-day bombardment of Fort Mifflin forced the Americans out. Two days later Fort Mercer fell and the British vessels pushed upriver in pursuit of the American fleet which was later scuttled at Gloucester.[28][29]

At the end of the year, Howe's fleet removed to Narragansett Bay where Pearl and her compatriots patrolled the coast and preyed on enemy shipping.[5][30] At dawn, on 25 July 1778, a large vessel was seen off Sandy Hook and Pearl, anchored nearby, was sent in pursuit. She came up with the chase at 09:00, which fought for an hour and a half before striking. The prize turned out to be the Industry, an American frigate of 26-guns operating under a letter of marque.[31]

Pearl was present when the French fleet from Toulon arrived at the end of July and was at the ensuing engagement in August.[32] The French force, under Comte d'Estaing, entered the bay on 29 July and attacked British positions on Conanicut and Goat Island the following day.[33] On 8 August, 4,000 French soldiers and sailors were landed to reinforce the 10,000 American troops who had just crossed from the mainland to lay siege to the British garrison on Rhode Island.[34]

Howe positioned his fleet off Point Judith on 9 August. D'Estaing had superior numbers and guns, so sailed out the next morning, fearing that the British might soon be reinforced.[35] A violent gale scattered the fleets and ended several days of manoeuvring, in which both commanders sought the weather gage.[36] When the British were eventually reunited, it was evident that repairs were required and they sailed for New York City on 15 August. D'Estaing's ships had fared even worse and were forced to retire to Boston.[37] Howe left for England in September 1778, and Pearl joined a squadron under Rear-Admiral John Byron, watching the French fleet in the harbour.[38][39]

Operations in the West Indies

D'Estaing's fleet of 15 ships of the line left Boston on 3 November 1778, two days after Byron's squadron had been blown off station and driven into Newport by more bad weather.[38][39] Pearl was despatched to carry news of the escape to Admiral Samuel Barrington; Byron was to follow two to three days later if he was unable to locate the French. Not knowing Barrington's precise whereabouts, Pearl at first sailed to Antigua, arriving on 4 December, before immediately heading for Barbados.[39] En route, she stopped a Dutch vessel which had encountered a French warship out of Boston on the previous night. From the information received, Linzee deduced that d'Estaing's fleet was somewhere near Barbados and arrived there himself on 13 December.[39]

On 10 December, William Hotham with a convoy of 5,000 troops, escorted by a small squadron comprising two 64-gun and three 50-gun ships of the line, a bomb vessel, and two frigates arrived at Barbados.[38] Here they were joined by Barrington's two ships of the line, before setting off to attack the island of St Lucia. On 13 December, the convoy landed troops on the west side of the island who quickly captured the batteries covering the bay.[40] With the support of these batteries, Barrington's much smaller fleet was twice able to repulse d'Estaing's when it arrived the following day. Although the French were able to land 7,000 troops of their own, British command of the high ground meant they were beaten off.[41] The French troops were re-embarked, and when d'Estaing's fleet left on 29 December, the island surrendered.[42][Note 2]

News of the capture of St Lucia was carried back to England in Pearl. She left Antigua on 16 February 1779 in the company of HMS Sultan with despatches from both Byron and Barrington, and arrived at Spithead on 22 March.[43] She was then paid off, sheathed in copper, and refitted at Plymouth.[5] She served for a short while in the Channel before returning to the North American Station under Captain George Montagu.[5]

On her return to the American continent in September, Pearl encountered the 28-gun Santa Monica off the Azores. Pearl left Fayal on 13 September where she had spent two days resupplying. At 06:00 the following morning, the Spanish frigate was spotted to the north-west and was brought to action after a three-and-half-hour chase. The Santa Monica surrendered after a two-hour engagement, having 38 men killed and 45 wounded. Pearl had 12 killed and 19 wounded.[44] The Santa Monica was a larger frigate than Pearl, at 956 tons burthen, but not as well armed; she was re-rated as a 36-gun when taken into British service.[45]

Pearl took part in an attack on a convoy from Caracas on 8 January 1780[5] comprising 22 ships, including seven Spanish men of war, and the entire convoy was taken. A proportion of the captured ships were carrying naval supplies and these were despatched to England with Pearl and HMS America as escorts, while the remainder were sent to Gibraltar.[46] Pearl later returned to North America, spending some time at Halifax, Nova Scotia before leaving, with HMS Robust, to join Admiral Marriot Arbuthnot's squadron off Sandy Hook on 3 July 1780, where preparations were being made to repel an expected attack by the French fleet.[47]

Arbuthnot set sail on 13 July, after being reinforced with six ships-of-the-line under Rear-admiral Thomas Graves. Hearing that the French fleet had put into Narragansett Bay on 17 July, Arbuthnot's squadron arrived on 22 July to find the French encamped on Rose Island and their ships strung out between there and Conanicut. Arbuthnot sent orders for transports from New York, in case the British Army thought an attack on the island necessary, then anchored his squadron off Block Island.[47] After re-provisioning on 6 August, the British squadron stationed itself off Newport, then retired to Gardiner's Island on 9 August, leaving on 17 August for an eight-day cruise between the Nantucket Shoals and the east end of Long Island, returning to lie off Martha's Vineyard.[47]

Pearl fell in with the 28-gun French frigate Esperance off Bermuda on 30 September 1780. After a two hour fight, Esperance broke off but Pearl pursued her and the two engaged in a running battle for a further two and a half hours, after which the Frenchman was forced to strike. She had 20 men killed and 24 wounded; Pearl had 6 men killed and 10 wounded.[48]

Battle of Virginia Capes

In January 1781, Arbuthnot had a French squadron blockaded in Newport. On 23 January, his ships were caught in a squall off the east end of Long Island which resulted in the loss of HMS Culloden and the dismasting of HMS Bedford. America was blown out to sea but turned up two weeks later undamaged.[49] Pearl escaped serious damage and was able to capture a French snow on 29 January.[50] The French, however, now had a numerical advantage; they broke out on 8 February and captured the British frigate Romulus.[49] The British brought Bedford back into service by salvaging the masts from the wreck of the Culloden and set sail to look for the French on 9 March.[51] The two forces discovered each other at 06:00 on 16 March in a thick fog some 40 nmi (74 km) off Cape Henry.[52] The British caught up by 13:00 and found themselves to windward of the French after some manoeuvring, where the increasingly strong winds and high seas prevented them from opening their lower gunports. The French held the lee and leaned away from their opponents; they were not so disadvantaged and could bring more and larger guns to bear. The fleets engaged by 14:30 with the heaviest action upon the leading three ships of the British vanguard.[53] The three ships were so badly damaged that the British were unable to pursue when the French broke off and turned towards Newport, so they put into Chesapeake Bay. The British casualties were 30 killed, 73 wounded, while the French had 72 killed and 112 wounded.[54] Pearl was too small to be in the line of battle and had stood off with the other frigates, incurring no loss or damage. She had responsibility for relaying signals during the battle.[55]

Arbuthnot's ships were seaworthy by 24 March and he set sail for Delaware, where he assumed that the French fleet had gone, but contrary winds forced him to return. Two days later, Pearl was sent out with Iris to search for the French but again was unable to locate them.[54][55]

Pearl remained in American waters until July 1782. She continued to harass enemy shipping, taking the French privateer Singe, a large polacca, on 10 July 1781[56] and the 8-gun American Senegal of 50 tons, on 19 August,[57] plus three merchant vessels before the year was out.[57] Two schooners[58] and three brigs were captured in 1782,[59] before Pearl paid off and returned to England for substantial repairs. The cost of repairs amounted to £19,267.13.8d and took until June 1784, after which she was laid up at Deptford.[5][Note 3]

Mediterranean service and the outbreak of war

Between July and December 1786, Pearl was undergoing a refit. She sailed to the Mediterranean on 22 March 1787 returning home in 1789 where she was recommissioned under Captain George Courtnay. She rejoined the Mediterranean fleet in May 1790.[5] Sometime in 1792, Pearl was taken out of service but was recalled the following year when France declared war on Britain once more. She was fitted out at Plymouth between June and August at a cost of £7,615, before sailing to the Irish Station under Captain Michael de Courcy where she served until November 1795. Following a small repair at Plymouth, costing £9,686, Captain Samuel James Ballard took command in February 1796.[5]

Aided by the 36-gun HMS Flora, Pearl captured the 24-gun privateer, Incroyable, on 14 April 1797. Reputed to be a very fast sailing vessel, Incroyable left her home port of Bordeaux on 2 April. She had yet to take a prize, when, on the morning of 11 April, she was seen and chased by Pearl. The next day, the two ships were some 200 nmi (370 km) off the west coast of Spain, when Flora appeared, forcing Incroyable to haul to windward. On 13 April, Incroyable became becalmed, allowing the British frigates to catch up, which they did at 23:45. After receiving a single broadside, the French privateer surrendered.[60]

In March 1798, Pearl sailed for the Leeward Islands via West Africa where on 24 April, she escaped from two French frigates.[5] While passing through the Îles de Los, an archipelago off the coast of Guinea, Pearl discovered an enemy squadron comprising four large ships at anchor and a brig under sail. As she approached, one of the ships hoisted a French flag and opened fire. Forced to run between two frigates, Pearl engaged both as she passed then hove to, continuing to fire for a further hour before making off with one, or possibly both frigates in pursuit.[61][62] The chase continued through the night and all through the following day before Pearl managed to escape, arriving at Sierra Leone on 27 April, where she was inspected for damage. She had been holed in several places, although all were above the waterline; her foretopgallant yard and fore yard had been shot away and a number of lower shrouds and other rigging had been cut through. In addition, two of her carronades had been dismounted, causing the death of one man.[61][Note 4] Pearl eventually arrived in the West Indies, capturing the 10-gun privateer, Scocvola,in October and the 12-gun privateer, Independence, in December. Both off the coast of Antigua.[5]

On 22 October 1799, Pearl was sent to the Mediterranean where she spent much of the following 12 months attempting to disrupt enemy trade by attacking the numerous merchant vessels along the European coast. In January 1800, she took a Spanish brig, and a French brig with accompanying settee.[5][64] Then on 9 February, near Narbonne, she drove ashore and destroyed, a large Genoese polacca of 14 guns. The crew escaped as did the small convoy of settees that were being escorted.[65] While off Marseilles, Pearl captured a Genoese brig and settee on 28 April, two more Genoese settees on 2 and 3 May[66] and, with HMS Hindostan, a Ragusan brig on 20 May.[67]

Cruising off Alicante in June and July, Pearl captured three more Ragusan ships, two of which were loaded with slaves, a French setee, two Spanish setees and a Xebec.[68][69] Then, on 20 July, the crew of Pearl took part in a cutting out expedition which resulted in the capture of two xebecs and six settees. Shortly after the action a storm blew up and three of the prizes had to be scuttled but not before the cargo was removed.[70][69] Pearl captured four more settees on 31 August 1800 and destroyed a further two on 11 October. On the same day, she took a French ketch on its way to Nice. Two Genoese ships were taken on 14 October and three French setees the following day while a fourth was burned.[71]

Pearl received a share of the prize money for a transport, wrecked off Minorca and salvaged on 20 October with the aid of the 18-gun sloop, Lutine, the 8-gun bomb vessel, Strombolo, and the 6-gun tender, Alexander. On 31 October, Pearl with Lutine, Strombolo, the 20-gun corvette Bonne Citoyenne and the 12-gun polacca, Transfer, took another transport from Port Mahon.[72]

Alexandria

In January 1801, a large expedition of 16,000 troops and more than 100 vessels was assembled in Malta in preparation for an invasion of Egypt. George Elphinstone's fleet, to which Pearl was attached, escorted the force to Aboukir Bay, arriving on 1 February 1801.[73] The Battle of Alexandria was brought to a successful conclusion when the French surrendered on 2 September, following a long siege.[74] In 1850, a medal with the clasp "Egypt" was retrospectively awarded to the surviving members of Pearl's crew, for their part in the campaign.[73][75]

Pearl, while cruising with the 32-gun HMS Santa Theresa on 28 February, took a Genoese merchant ship on its way home, laden with goods from Marseilles. The two British frigates later managed to save some cargo from a sinking Genoese tartan and a French tartan they had scuttled. Both ships were out of Marseilles.[76] On 20 March, a French ship bound for Alexandria was intercepted and captured by Pearl, Santa Teresa and HMS Minerve.[76] With the 16-gun sloop Peterel and 14-gun brig Victorieuese, Pearl seized a Genoese ship carrying arms to Alexandria on 29 April. The three British ships took a French aviso, also going to Alexandria, on the same day.[77] On 1 July, Pearl took a small privateer.[5]

Siege of Porto Ferrajo

Pearl was in John Borlase Warren's squadron when it was called upon to relieve the British garrison at Porto Ferrajo; under siege since the beginning of May 1801.[78] The arrival of the British ships on 1 August, caused the two French frigates guarding the port to retreat to Leghorn. Warren then initiated a blockade of the island.[79] The two escaped frigates were later brought to action on 2 September when Pomone, Phoenix and Minerve recaptured Succès and destroyed Bravoure after she had run aground.[Note 5][81]

The next day at 14:30, Phoenix, Pomone and Pearl were cruising off the west side of the island, when they spotted the 40-gun Carrère, on her passage from Porto-Ercole to Porto-Longone with a convoy of small vessels. Pearl sailed to cut off the frigate's destination and only Pomone got close enough to engage. Carrère struck to her after a 10-minute action but the convoy managed to escape.[79][82]

Pearl, Pomone, Renown, Gibraltar, Dragon, Alexander, Généreux, Stately and Vincejo, supplied nearly 700 seamen and marines for an attack on the French batteries investing the town. The action took place on 14 September but was only partially successful, and eight days later the British ships left Elba. Porto Ferrajo however, remained in British hands until the end of the war.[83]

Fate

After the Treaty of Amiens, Pearl remained in the Mediterranean under Ballard until May 1802 when she returned to England and was laid up in ordinary at Portsmouth.[84] In April 1804, she was fitted out as a slop ship.[Note 6] In 1812, she was laid up in ordinary once more, then fitted as a receiving ship in April 1814. Renamed Protheé in March 1825 she was eventually sold in 1832 for £1,230.0.00d.[5]

Prizes

Vessels captured or destroyed for which Pearl's crew received full or partial credit[Note 7] | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Notes

- Winfield's book gives the date of this change as December 1777,[5] however, copies of Linzee's journal, reprinted in Morgan's Naval Documents of the American Revolution indicate he was in command at the capture of Mosquito in July.[18]

- Clowes has Pearl as one of the two frigates (the other being HMS Venus) in Hotham's fleet at St Lucia.[38] This fleet left New York on 4 November however[38] and the London Gazette has Pearl with Byron until 17 November.[39] The Gazette also records that Pearl did not arrive in Barbados until the day after the fleet had left.[39]

- Winfield's book gives the year of these repairs as 1884 but this is a clear and obvious typographical error because 1786 is the following year in Winfield's timeline and Pearl was sold in 1825.[4]

- William James claims the ship that chased Pearl was the 36-gun Régénérée,[61] while Onésime-Joachim Troude, in his third volume of "Batailles navales de la France", states the 40-gun Vertu was the ship in pursuit.[63] Clowes book says that both the frigates chased Pearl.[62]

- Succès was previously HMS Success, captured off Gibraltar by Ganteaume's force on 9 February 1801.[80]

- A slop ship was a vessel where sailors' clothing (slops) were stored and distributed.[85]

- Does not include prizes taken in fleet actions where Pearl was not actively engaged

Citations

- Winfield pp.193–195

- Winfield p.195

- Winfield p.193

- Winfield pp.195–196

- Winfield p.196

- "No. 11677". The London Gazette. 22 June 1776. p. 1.

- McCullough, David (2005). 1776. Simon & Schuster. p. 204. ISBN 0-7432-2671-2.

- Beatson p.164

- McCullough p.208

- McCullough pp.210-211

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.72

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.295

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.80

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.77

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.150

- "No. 11786". The London Gazette. 8 July 1777. pp. 2–3.

- "No. 12222". The London Gazette. 4 September 1781. p. 2.

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.IX) pp.232-233

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.IX) p.778

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.IX) p.809

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.IX) pp.809-810

- Lossing pp. 291–292

- Lossing p.298

- Lossing p.292

- Beatson p.269

- Lossing pp. 295–296

- Beatson pp.269-270

- Lossing pp. 296–299

- Allen p.241

- "No. 11951". The London Gazette. 6 February 1779. pp. 3–4.

- Beatson p.380

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.406

- Clowes (Vol.III) pp.402–403

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.403

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.405

- Clowes (Vol.III) pp.405–408

- Clowes (Vol.III) pp.408–409

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.428

- "No. 11955". The London Gazette. 20 February 1799. pp. 1–2.

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.429

- Clowes (Vol.III) pp.431–432

- Clowes (Vol.III) p.432

- "No. 11963". The London Gazette. 20 March 1779. p. 1.

- "No. 12018". The London Gazette. 11 July 1758. p. 1.

- Clowes (Vol.IV) p.33

- "No. 12056". The London Gazette. 8 February 1780. p. 1.

- "No. 12122". The London Gazette. 26 September 1780. p. 4.

- "No. 12135". The London Gazette. 11 November 1780. pp. 1–2.

- "No. 12181". The London Gazette. 21 April 1781. p. 1.

- "No. 12243". The London Gazette. 17 November 1781. p. 2.

- "No. 12181". The London Gazette. 21 April 1781. p. 2.

- Mahan p.171

- Mahan pp.171–172

- Mahan p.173

- "No. 12181". The London Gazette. 21 April 1781. p. 3.

- "No. 12227". The London Gazette. 22 September 1781. p. 1.

- "No. 12279". The London Gazette. 16 March 1782. p. 1.

- "No. 12306". The London Gazette. 18 June 1782. p. 5.

- "No. 12398". The London Gazette. 17 December 1782. p. 2.

- "No. 14003". The London Gazette. 8 April 1797. pp. 364–365.

- James (Vol.II) p.219

- Clowes (Vol.IV) p.510

- Troude p.130

- "No. 15255". The London Gazette. 6 May 1800. p. 442.

- "No. 15242". The London Gazette. 25 March 1800. p. 297.

- "No. 15278". The London Gazette. 22 July 1800. p. 843.

- "No. 15278". The London Gazette. 22 July 1800. p. 844.

- "No. 15301". The London Gazette. 11 October 1800. p. 1169.

- "No. 15301". The London Gazette. 11 October 1800. p. 1170.

- "No. 15294". The London Gazette. 16 September 1800. p. 1062.

- "No. 15358". The London Gazette. 25 April 1801. p. 446.

- "No. 16017". The London Gazette. 7 April 1807. p. 441.

- Long p.112

- Long p.113

- "No. 21077". The London Gazette. 15 March 1850. pp. 791–792.

- "No. 15428". The London Gazette. 17 November 1801. p. 1385.

- "No. 15428". The London Gazette. 17 November 1801. p. 1386.

- James (Vol.III) p.95

- James (Vol.III) p.96

- James (Vol.III) p.97

- James (Vol.III) pp.96–97

- "No. 15426". The London Gazette. 10 November 1801. p. 1354.

- James (Vol.III) p.98

- The Naval Chronicle, Containing a General and Biographical History of the Royal Navy of the United Kingdom, with a Variety of Original Papers on Nautical Subjects. XI. London: J. Gold. 1804. p. 510.

- James, Charles (1810). A New and Enlarged Military Dictionary: In French and English; in which are Explained the Principal Terms ... of All the Sciences that are ... Necessary for an Officer and Engineer. II. London: T. Egerton.

- "No. 12222". The London Gazette. 4 September 1781. p. 2.

- "No. 11769". The London Gazette. 10 May 1777. p. 3.

- "No. 12222". The London Gazette. 4 September 1781. p. 3.

- "No. 11786". The London Gazette. 8 July 1777. p. 3.

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) p.185

- Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Vol.VIII) pp.300-301

- "No. 11951". The London Gazette. 6 February 1779. p. 3.

- "No. 11951". The London Gazette. 6 February 1779. p. 4.

- "No. 11769". The London Gazette. 10 May 1777. p. 2.

- "No. 12008". The London Gazette. 21 August 1779. p. 2.

- "No. 12018". The London Gazette. 28 September 1779. p. 1.

- "No. 12243". The London Gazette. 17 November 1781. p. 2.

- "No. 12135". The London Gazette. 11 November 1780. p. 1.

- "No. 15199". The London Gazette. 29 October 1799. p. 1121.

- "No. 15092". The London Gazette. 22 December 1798. p. 1238.

- "No. 15466". The London Gazette. 27 March 1802. p. 325.

- "No. 15255". The London Gazette. 6 May 1800. p. 442.

- "No. 15278". The London Gazette. 22 July 1800. p. 844.

- "No. 15301". The London Gazette. 11 October 1800. p. 1169.

- "No. 15294". The London Gazette. 16 September 1800. p. 1062.

- "No. 15358". The London Gazette. 25 April 1801. p. 446.

- "No. 15999". The London Gazette. 10 February 1807. p. 180.

- "No. 15475". The London Gazette. 27 April 1802. p. 433.

- "No. 15428". The London Gazette. 17 November 1801. p. 1386.

- "No. 15534". The London Gazette. 20 November 1802. p. 1229.

- "No. 15529". The London Gazette. 2 November 1802. p. 1157.

- "No. 15552". The London Gazette. 22 January 1803. p. 107.

- "No. 15555". The London Gazette. 1 February 1803. p. 141.

References

- Allen, Joseph (1852). Battles of the British Navy Volume I. London: Henry Bohn. OCLC 935205877.

- Beatson, Robert (1790). Naval and Military Memoirs of Great Britain: From the Year 1727 to the Present Time, Volume IV. London: J. Strachan. OCLC 1003934064.

- Clowes, William Laird (1996) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume III. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-012-4.

- Clowes, William Laird (1997) [1900]. The Royal Navy, A History from the Earliest Times to 1900, Volume IV. London: Chatham Publishing. ISBN 1-86176-013-2.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume II, 1797–1799. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-906-9.

- James, William (2002) [1827]. The Naval History of Great Britain, Volume III, 1800–1805. London: Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-907-7. 0811700232

- Long, W. H. (2010). Medals of the British Navy and how they were won. United Kingdom: Lancer Publishers. ISBN 978-1-935501-27-5.

- Lossing, Benson J. (1852). A Pictorial Field Book of the Revolution, Volume II. New York: Harper and Brothers Publishing. OCLC 560599621.

- Mahan, A. T. (2013) [1913]. The Major Operations of the Navies During the War of American Independence. London: Sampson Low, Marston and Co. ISBN 9781481236942.

- Morgan, W. J. (editor) (1964). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Volume VIII). Washington: United States Naval History Division. OCLC 630221256.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Morgan, W. J. (editor) (1986). Naval Documents of the American Revolution (Volume IX). Washington: United States Naval History Division. OCLC 769293550.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Troude, Onésime-Joachim (1868). Batailles navales de la France Tome 3. Paris: Challamel. OCLC 982607992.

- Winfield, Rif (2007). British Warships in the Age of Sail 1714–1792: Design, Construction, Careers and Fates. Seaforth Publishing. ISBN 978-1-84415-700-6.