HMS Augusta (1763)

HMS Augusta was a 64-gun third rate ship of the line of the Royal Navy, launched on 24 October 1763 at Rotherhithe.[1]

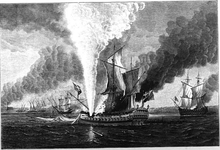

_RMG_J3173.png) Augusta | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name: | HMS Augusta |

| Ordered: | 13 January 1761 |

| Builder: | Wells and Stanton, Rotherhithe |

| Launched: | 24 October 1763 |

| Fate: | Burned, 22 October 1777 |

| General characteristics [1] | |

| Class and type: | St Albans-class ship of the line |

| Tons burthen: | 138133⁄94 (bm) |

| Length: | 159 ft (48 m) (gundeck) |

| Beam: | 44 ft 4 in (13.51 m) |

| Depth of hold: | 18 ft 10 in (5.74 m) |

| Propulsion: | Sails |

| Sail plan: | Full rigged ship |

| Armament: |

|

She was accidentally destroyed by fire on 22 October 1777 during the Battle of Red Bank.[2]

Loss

On the evening of 22 October 1777, the Augusta and several other warships had sailed up the Delaware River to a point a short distance below some man-made chevaux de frise obstructions[3] in order to fire at Fort Mercer the following day. As the tide fell, both Augusta and HMS Merlin (16) went aground. Despite attempts during the night by HMS Roebuck (44) to free Augusta from its predicament, the warship remained hard aground. About 9:00 AM on 23 October, a general action started with HMS Pearl (32) and HMS Liverpool (28) joining other vessels in the bombardment. The British ships were engaged by Fort Mifflin and the Pennsylvania Navy, which launched four fire ships. At about 2:00 PM, the Augusta caught fire near its stern, according to an American eyewitness. The fire spread rapidly and soon the entire vessel was wrapped in flames. After about an hour the fire reached the magazine and the ship exploded. The blast smashed windows in Philadelphia and was heard 30 miles (48 km) away in Trappe, Pennsylvania. The loss of the Augusta was attributed to various causes. The British claimed that the blaze was started when wadding from the guns set the rigging on fire or that the crew intentionally set the blaze. Some Americans asserted that Augusta was ignited by a fire ship while others stated that its loss was caused by red-hot shot from Fort Mifflin. John Montresor, the British officer in charge of the Siege of Fort Mifflin, wrote that one lieutenant, the ship's chaplain and 60 of Augusta's ratings were killed while struggling in the water. Soon after, the crew of Merlin abandoned ship and set their ship on fire. It blew up later in the day.[4]

Legacy

The Augusta was the largest British vessel lost in combat by the Royal Navy in either the Revolutionary War or in the War of 1812.[5]

In the 1870s, rumors of gold in the wreck, which was still partially visible in the river, led to a recovery efforts that removed tableware, a watch, coins, and three cannons. An unsuccessful attempt to move the ship for display in the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia failed, leaving the ship grounded again at Gloucester City, New Jersey. There, it was made a tourist attraction with paid admission for a few years before it broke up in a heavy storm. The Daughters of the American Revolution took much of the wood to its Washington, DC headquarters and used it to recreate an English period dining room. Other pieces washed up on Gloucester City beaches and were collected by citizens. One Paulsboro resident collected 14 staircase pedestals, donating 12 to the Smithsonian and one to the Gill Memorial Library in Paulsboro.[6]

Notes

- Lavery, Ships of the Line, vol. 1, p. 178.

- Ships of the Old Navy, Augusta.

- "Stealth weapon found in the Delaware River off Bristol makes Brandywine museum debut". buckscountycouriertimes.com.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. pp. 171–174. ISBN 0-8117-0206-5.

- Miller, Nathan (2000). Broadsides The Age of Fighting Sail, 1775-1815. John Wiley & Sons, Inc. p. 46. ISBN 0-471-18517-5.

- Colimore, Edward (26 October 2007). "The HMS Augusta has New Life". gloucestercitynews. Retrieved 1 February 2017.

References

- Lavery, Brian (2003) The Ship of the Line - Volume 1: The development of the battlefleet 1650-1850. Conway Maritime Press. ISBN 0-85177-252-8.

- McGuire, Thomas J. (2007). The Philadelphia Campaign, Volume II. Mechanicsburg, Penn.: Stackpole Books. ISBN 0-8117-0206-5.

- Phillips, Michael. Augusta (64) (1763). Michael Phillips' Ships of the Old Navy. Retrieved 1 September 2008.

External links