Grosvenor Canal

Grosvenor Canal was a canal in the Pimlico area of London, opened in 1824. It was progressively shortened, as first the railways to Victoria Station and then the Ebury Bridge housing estate were built over it. It remained in use until 1995, enabling barges to be loaded with refuse for removal from the city, making it the last canal in London to operate commercially. A small part of it remains among the Grosvenor Waterside development.

| Grosvenor Canal | |

|---|---|

The view from the entrance lock towards the River Thames | |

| Specifications | |

| Status | Closed, mostly infilled |

| History | |

| Date of first use | 1824 |

| Date completed | 1825 |

| Date closed | 1858, 1925, 1990s |

| Geography | |

| Connects to | River Thames |

Grosvenor Canal | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

In the early eighteenth century, there were marshes and a tidal creek on the north bank of the Thames near Pimlico. The Chelsea Waterworks Company obtained an Act of Parliament in 1722; they were authorised to take water from the Thames via one of more "Cutt or Cutts". These fed the water into the marshes, and a tide mill was used to pump the water to reservoirs at Hyde Park and St James's Park as the tide ebbed. The reservoirs supplied west London with drinking water. The land between the river and the later site of Victoria Station was owned by Sir Richard Grosvenor, who leased it to the company in 1724. They enlarged the existing creek and built the tide mill, which continued to work until 1775, after which the pumping was performed by a steam engine.[1]

The company were able to take water directly from the Thames following the granting of another Act of Parliament in 1809. They continued to lease the land until 1823, when the lease expired. In the following year, the Earl of Grosvenor then decided to turn the creek into a canal, building a lock near the junction with the Thames and a basin at the upper end, around 0.75 miles (1.21 km) inland. Most of the commercial traffic appears to have been coal, to supply the neighbourhood.[1] The resident engineer for the construction of the tidal lock and upper basin was John Armstrong, originally from Ingram, Northumberland. Having trained as a millwright in Newcastle, he worked on a number of bridge projects under several of the major civil engineers of the time, including Thomas Telford, William Jessop and John Rennie, before taking on the Grosvenor Canal project. It was one of the few times he worked independently as a civil engineer.[2] The canal opened in 1824,[3] and Chelsea Waterworks continued to extract water from it, until the passing of the Metropolis Water Act in 1852, which prohibited extraction from the Thames below Teddington Lock. They moved to Seething Wells, Surbiton in 1856.

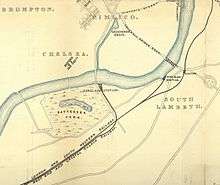

The canal originally stretched from the Thames near Chelsea Bridge to Grosvenor Basin on the current site of Victoria station. It is difficult to tell whether all of the clear area marked Grosvenor Basin on the 1850 map was actually water,[4] but the size of the basin was described as "immense" in 1878.[5] When the station was built around 1858, the Victoria Station and Pimlico Railway obtained an Act of Parliament which ratified an agreement between them and the Duke of Westminster, allowing the station to be built on the basin site, and a new towpath to be constructed between Ebury Bridge and Eccleston Bridge. The station opened on 1 October 1860. As the railways continued to expand, more room was needed, and another Act was obtained by the London, Brighton and South Coast Railway in 1899, which allowed the canal above Ebury Bridge to be closed. This took place around 1902, resulting in the canal being half its original length. Since 1866, a local authority called the Vestry of St George, Hanover Square had used the canal to transport household refuse away from the area. They were based close to the end of the canal at Ebury Bridge. Following the cutback of the canal to this point, the Duke of Westminster sold what was left of the canal to Westminster City Council, and its primary function became rubbish removal.[6]

Around 1925 it was halved in length again to allow Ebury Bridge Estate to be built by Westminster City Council. The lower portion of the canal was kept as a dock, allowing the council to continue loading barges with rubbish. In July 1928, the canal closed for nearly a year, while major improvements were made to facilitate the barge traffic.[7] At its peak, 8,000 tons of refuse were loaded onto barges each week, and the barge traffic lasted until 1995,[8] making it the last canal in commercial operation in London. The area has since been redeveloped as Grosvenor Waterside. The lock and the basin between it and the Thames have been retained,[9] as has some of the upper basin.[10] The lock has three sets of gates, two facing away from the Thames, and a third set facing towards the Thames, to cope with high tides where the river level exceeds that in the canal.[8] The third set was first fitted some time between 1896 and 1916.[11]

Development

In 2000 planning permission was granted to turn the dock site into high end housing known as Grosvenor Waterside. Although there is no access to boats, the development has included an operational swing bridge over the lock, and the inner dock has been refurbished to include mooring pontoons.[12][13]

Route

Grosvenor Road, part of the London Embankment, runs close to the river, and the canal passes under it where it joins the Thames. On the north side of the road is the Lower Basin, which is tidal and is normally empty at low tide. The lock is immediately to the north of it, while above the lock was a wider section to the east, called the Upper Basin. In 1875 there was a timber yard to the west of the Upper Basin, behind which were the offices of the Chelsea Water Works. A saw mill and an iron works had been built between the timber yard and the canal by 1916, and a large building marked Corporation Depot occupied the west bank to the end of the truncated canal in 1951. By 1896, a sewage works had been built on the narrow strip of land between the basin and the railway tracks to the east, consisting of cooling ponds and a pumping station.[11] This was the Western Pumping Station, completed by 1875, and the final part of the main drainage system for London. Four high-pressure condensing beam-engines, housed in a building 71 feet (22 m) tall, developing 360 hp (270 kW) raised sewage by 18 feet (5.5 m) from a low level sewer, to pump it to the Abbey Mills station at Barking. The station could pump 55 million gallons per day (250 Mld), and a backup non-condensing engine was provided in case of failure of any of the main engines.[5]

Between the upper basin and Ebury Bridge, the railway hemmed in the east bank, while to the left there was a saw mill and a wider section with wharves. The saw mill had become a motor car depot and works by 1916, and the whole area was part of the Ebury Bridge housing estate in 1951. Between Ebury Bridge and Elizabeth Bridge, there were a series of wharves, labelled Victoria Wharf, Bangor Slate Wharf, Ebury Wharf, Commercial Wharf and Lime Wharf on a wide section of canal, after which it narrowed, and was flanked by a livery stables, Baltic Wharf, Eaton Wharf and Elizabeth Bridge Wharf. The buildings were all still there in 1896, but only Ebury, Lime and Baltic wharves were named. All of them had disappeared beneath the railway tracks by 1916. Beyond Elizabeth Bridge there was a short wide section, flanked by St George's Wharf in 1875 and a narrow section bordered by various types of works. The wharf was called Eaton Wharf in 1896, and the buildings were no longer named. Before Eccleston Bridge, the canal ended, its width reduced by the tracks swinging westwards to reach the western platforms of the station.[11]

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes

a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Site of Grosvenor Basin | 51.4946°N 0.1454°W | TQ288789 | Under Victoria Station |

| Site of Eaton Wharf | 51.4926°N 0.1470°W | TQ287787 | Under railway sidings |

| Site of Ebury Wharf | 51.4908°N 0.1490°W | TQ286784 | now a car park |

| Upper basin | 51.4875°N 0.1492°W | TQ286781 | |

| Lower basin | 51.4862°N 0.1494°W | TQ285779 |

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Grosvenor Canal. |

References

- Hadfield 1970, p. 139

- Skempton 2002, p. 21

- Hadfield 1970, pp. 272–273

- Ordnance Survey, 1:5280 map, 1850

- Walford 1878, pp. 39–49

- Hadfield 1970, p. 238

- "London's Minor Canals". London Canal Museum. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Cumberlidge 2009, p. 378

- "The Grosvenor Canal". London Canals. Archived from the original on 21 January 2012. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Google satellite view

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 maps, 1875, 1896, 1916, 1951

- "Grosvenor Waterside". My London Home. Archived from the original on 20 April 2013. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

- "Grosvenor Waterside". Caro Point. Archived from the original on 28 February 2012. Retrieved 24 November 2012.

Bibliography

- Cumberlidge, Jane (2009). Inland Waterways of Great Britain (8th Ed.). Imray Laurie Norie and Wilson. ISBN 978-1-84623-010-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadfield, Charles (1970). The Canals of the East Midlands. David and Charles. ISBN 0-7153-4871-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Skempton, Sir Alec; et al. (2002). A Biographical Dictionary of Civil Engineers in Great Britain and Ireland: Vol 1: 1500 to 1830. Thomas Telford. ISBN 0-7277-2939-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Walford, Edward (1878). Old and New London: Volume 5. Centre for Metropolitan History. British History Online.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)