Rolle Canal

The Rolle Canal (or Torrington Canal) in north Devon, England, extends from its mouth into the River Torridge at Landcross 6 miles southwards to the industrial mills and corn-mills at Town Mills (now called "Orford Mill"), Rosemoor, Great Torrington[1] and beyond to Healand Docks and weir on the Torridge, where survive the ruins of Lord Rolle's limekilns, upstream of today's Rosemoor Garden.[2] Town Mills were built by Lord Rolle and were powered by a stream which flowed past his seat of Stevenstone to the east of Great Torrington and also supplied water to the canal. Rosemoor and North and South Healand farms were part of Lord Rolle's Stevenstone estate on the east bank of the Torridge.

Rolle Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

.jpg)

Description

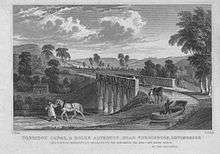

The canal comprises a sea lock at Landcross, a 60-foot inclined plane at Weare Giffard and an aqueduct of five arches over the River Torridge at Beam.[3] At the terminus of the canal at the limekilns at Rosemoor a leat supplies the canal to ensure a constant water level, which channels-off water from the River Torridge at Healand (or Darkham) Weir,[4] rebuilt in 1837.[5]

Lime kilns

The canal terminates beyond "Rowes Moor" (modern: Rosemoor) at a group of lime kilns designed by James Green. These consist of five large pots, each one 14 ft in diameter and 20 ft deep, arranged consecutively in a straight line along a wharf. Railway tracks led from the canal up a ramp to the top of the pots where a flat area existed for the storage of lime and fuel (culm/anthracite) pending burning. An office for the site forman was situated at the upper level. These kilns are derelict in 2013.[4]

History

The construction of the canal started in 1823 as a private venture financed largely by John Rolle, 1st Baron Rolle (died 1842), one of whose principal seats was at Stevenstone, east of Great Torrington. He was the largest landowner in Devon and owned much land around Torrington, including the estate of Beam, where continues to exist a mansion house which had served as a home for junior members of the Rolle family. Other shareholders in the company were William Tardrew of Annery, Monkleigh and Richard Pine-Coffin of Portledge,[6] who owned land on which the northerly section of the canal was constructed between the Rolle estate of Beam and the end of the canal at Landcross.

The canal was built largely without permission, with an act of Parliament eventually being granted for this purpose in 1835.[7] The idea for the canal had been proposed originally by Lord Rolle's father Denys Rolle but for various reasons nothing had come of those plans. The function of the canal was to import limestone from Wales to be burnt with coal, also imported, at inland kilns to make lime fertiliser which would greatly increase the fertility, and thus the value, of agricultural land. Marland Clay, mined south of Torrington, was to be exported via the seaport of Bideford, at the estuary of the River Torridge, for the making of bricks.

More generally the canal was to link the industrial mills at Great Torrington, some of which were owned by Lord Rolle, to the seaport of Bideford on the River Torridge. James Green was employed as the lead engineer.[8] Lord Rolle laid the foundation stone of the aqueduct in a ceremony which included the firing of a cannon, which unfortunately exploded, causing injury to a man by the name of John Hopgood, whom Rolle compensated with a year's salary.[1] A stone tablet on the north parapet of the Beam Aqueduct is inscribed:

The first stone of this aqueduct was laid by the Right Honourable John Lord Rolle, Baron Rolle of Stevenstone in the county of Devon, on the 11th day of August 182(1?) in the presence of the mayor, corporation and feoffees of Great Torrington and other persons assembled to witness the commencement of the (word chiselled out) CANAL undertaken at the sole expense of his Lordship. James Green Engineer.

The canal was completed in 1827 at a cost of between £40,000 and £45,000.[3] The canal shared many design features with the Bude Canal, unsurprisingly as the Bude Canal had partly inspired the scheme and shared the same lead engineer. Similarities included the use of trains of tub boats and of canal inclined planes rather than locks. The inclined plane was powered by a water wheel. The canal received its water supply from a weir on the River Torridge which also supplied two mills with power.[9]

Leased to George Braginton

In about 1852, some ten years after Lord Rolle's death, the canal was leased to George Braginton (1808–1886),[10] of Moor House, St Giles in the Wood, (the centre of the Rolle's Stevenstone estate) several times Mayor of Great Torrington, described in 1830 as "canal agent to Lord Rolle, and Portuguese vice consul for the Devonshire coast, in the Bristol channel".[11]

George's father was Richard II Braginton (1784–1869), of Great Silver, in the parish of Great Torrington, employed by Lord Rolle since 1814 and described in Lord Rolle's will proved in 1842 as "my steward at Stevenstone" was bequeathed £200, with a further £40 to "William Braginton one of his sons". Richard II thus played the important role of steward of Stevenstone during the time of Mark Rolle's minority from the death of Lord Rolle in 1842 to 1856. Thus it was possibly Richard II who advised the trustees of Mark Rolle to grant the lease to his son. Richard II married Ann Dwerryhouse of Liverpool in 1806.

George's grandfather was Richard I Braginton (1752–1812) who had been quartermaster-serjeant of the South Devon Militia, of which Lord Rolle was colonel. He died at Leicester and had been well regarded by Lord Rolle who erected a gravestone to his memory in St Martin's Church, Leicester, inscribed as follows:[12]

Beneath are deposited the remains of Richard Braginton Quarter Master Serjeant of the South Devon Militia who expir'd suddenly in this Town on his march to Nottingham[13] in the night of 15th of February 1812 after retiring to rest in perfect health AGED 60 YEARS He served 40 in the said Regiment with unabated Zeal, diligence and Loyalty to his King; and firm attachment to his Country; While his private conduct was equally commendable. For Rectitude, Probity and Sobriety He was esteem'd by his Officers and beloved by his fellow Soldiers. To perpetuate the remembrance of his worth, This stone was caus'd to be erected By his Colonel Lord ROLLE. Reader! may this additional Example of the awful uncertainty of Life prove a warning to thee to prepare for a similar fate, by a faithful discharge of the duties of thy station; and by an humble reliance on the merits of thy Redeemer.

George was a merchant and banker, and owned at least one ship, the Margaret, a brigantine of 139 tons built in Bideford in 1835. This was later owned by his younger brother William Dwerryhouse Braginton (died 1888), merchant and substantial shipowner[14] of Northam, near Bideford, who was declared bankrupt in 1879 and died at Bristol in 1888. George had also become bankrupt in 1865 on the failure of his bank, Braginton, Rimington & Co. He then faced several lawsuits for his "rash and hazardous dealings", and moved away to Compton Giffard. In 1874 his bankruptcy was discharged. He died in 1886 and was buried in Ford Park Cemetery, Plymouth.

George had six children by his wife Margaret Grace Vicary (died 1868), but his only two sons both died as infants, George Vicary Braginton (1840–1842) and Richard George Braginton (1849–1850). George erected a large chest tomb to his infant sons in St Giles's churchyard, and later next to it he buried his parents Richard II Braginton (died 1869) and Ann Dwerryhouse (died 1866), commemorated by a gravestone.

Exactly when the lease to George Braginton ended is unknown, but certainly no later than 1865.[15] On the termination of the lease, control of the canal passed to Lord Rolle's adoptive heir Mark Rolle (1835–1907), a younger son of Lord Clinton and the nephew of his second wife.[16]

Closure and sale

In 1871 the canal was closed and sold to the London and South Western Railway to form the trackway of the proposed new railway from Bideford to Torrington. At one point the railway company wished to abandon the project but at Mark Rolle's insistence the railway was built.[16] The track followed the canal in several stretches, not sitting within the former canal but on elevated ground beside it. The railway was dismantled during the 20th century and the trackway now forms part of the Tarka Trail cycleway.

Some parts of the canal are still visible today, including the Beam Aqueduct, now a viaduct carrying a new entrance drive to Beam Mansion, now an adventure holiday centre. The sea lock also survives, without its gates, as do parts of the inclined plane. The Annery kiln near Weare Giffard lies close to the old canal, between it and the River Torridge, and is visible from the Tarka Trail. The canal has been designated a Devon County Wildlife Site.[17]

Restoration

The Beam section of the canal is still owned by the heir of Lord Rolle, Lord Clinton and is managed by the family's management company, Clinton Devon Estates, still possibly the largest landowner in Devon.

Parts of the canal have been under restoration since 1988.[18] Clinton Devon Estates plan to restore the Beam estate section of the canal after 2013, and in 2000 completed restoration of the old stone bridge which took the old driveway from Beam Mansion northward over the canal, which passes under through a narrow tunnel.[19] Some work on the sea lock was carried out in 2006 involving re-pointing and rebuilding the eastern wall.[17]

The canal in fiction

The Beam Aqueduct is referred to as the "canal bridge" in Henry Williamson's Tarka the Otter.[20]

Further reading

Scrutton, S. (2006). Lord Rolle's Canal. Torrington: Susan Scrutton.

Hughes, B. (2006). Rolle Canal and the North Devon Limestone Trade. Bideford: Edward Gaskell Publishers. ISBN 1898546924.

References

- Lost canals and Waterways of Britain Ronald Russell page 96 ISBN 0-7153-8072-9

- http://www.bidefordpeople.co.uk/event/Rolle-Canal-Walk-RHS-Rosemoor-Garden/event-13049762-detail/event.html

- Industrial Archaeology Aids to recording (6) page 76

- http://www.therollecanal.co.uk/index.php/the-canal/lime-kilns/

- http://www.therollecanal.co.uk/wp-content/gallery/1800s/healandbluesml.gif

- http://www.therollecanal.co.uk/index.php/history/who/

- The Statutes of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Ireland. George Eyre and Andrew Strahan, Printers to the King's Most Excellent Majesty. 1835. p. 1084.

- Lost canals of England and Wales Ronald Russell page 79 ISBN 0-7153-5417-5

- Leone Levi, ed. (1865). Annals of British Legislation. Smith, Elder. p. 381.

- Following biographical details of Bragington family from

- London and Provincial New Commercial Directory, London, J. Pigot & Co. (1830)

- Transcription from Archived 3 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- Quoted from: "The Regiment of Militia of which the 7th South Devon Battalion probably formed a company was in the area due to serious rioting by workers (Luddites) when more machinery was introduced to manufacturing industries (i.e. job losses). The Militia had previously been in the South East district guarding French prisoners. Extract from a letter to Ken Robinson dated 16 Apr 1993 from L J Murphy Museum Attendant for Curator, The Regimental Headquarters, The Devonshire and Dorset Regiment, Myvern Barracks, Exeter EX2 6AE"

- Ships owned by William Braginton, quoted from : "William Rennie, a barque of 237 tons built in Liverpool in 1850; Louisa Braginton, a barque of 280 tons built in Bideford, Devon in 1856; Annie Braginton, a barque of 413 tons built in South Shields, Durham in 1860; Georgiana, a brigantine of 257 tons built in Bideford that was involved in a collision with the brig Orient in April 1867 at Appledore; Florence Braginton, a barque of 367 tons built in Sunderland, Durham that collided with the barque Superb off the coast of Norfolk in Dec 1864; Clara Louisa, a brig of 214 tons build in Bideford in 1854; and Margaret, a brigantine of 139 tons, build in Bideford in 1835, and originally owned by William's brother George. Available records show that the Annie Braginton sailed to places as varied as New York, Buenos Aires, Penang, Singapore, Bombay and Nelson, New Zealand. She was wrecked off the coast of India in 1884. The Louisa Braginton is known to have made her inaugural ocean voyage between Liverpool and South America. In 1860, her captain was tried in Liverpool for bringing Chilean political prisoners to the United Kingdom, and in September of 1866, she sailed from New York for the United Kingdom but never arrived. William Rennie was lost in the Bay of Biscay in 1856, however, the captain and crew were rescued. The Florence Braginton was sold at auction in 1867, and but lost in 1877 off Cape Horn".

- The Canals of Southwest England Charles Hadfield Page 139-140 ISBN 0-7153-8645-X

- Paget-Tomlinson, Edward (2006). The Illustrated History of Canal & River Navigations 3rd edition. Landmark Publishing Ltd. p. 189. ISBN 1-84306-207-0.

- "Canal comes back to life". North Devon Gazette. 17 August 2006. Retrieved 1 November 2008.

- North Devon Gazette, 17 August 2006

- Brass plaque affixed to bridge: "Clinton Devon Estates: Beam Canal and Bridge renovated Millennium 2000", with Clinton coat of arms above

- The Country Canal Ronald Russell ISBN 0-7153-9169-0 Page 124