Hackney Canal

The Hackney Canal was a short canal in Devon, England, that linked the Hackney Clay Cellars to the River Teign. It was privately built by Lord Clifford in 1843, and throughout its life carried ball clay for use in the production of pottery. It closed in 1928, when its function was replaced by road vehicles.

| Hackney Canal | |

|---|---|

The railway bridge over the entrance to the canal. The lock was just beyond the bridge. | |

| Specifications | |

| Locks | 1 |

| Status | mostly filled in |

| History | |

| Date of act | Privately built |

| Date of first use | 1843 |

| Date closed | 1928 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Hackney Clay Cellars |

| End point | River Teign |

Hackney Canal | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

History

The area to the north of the River Teign, particularly near to Chudleigh Knighton, Kingsteignton and Preston, was an important source of ball clay in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. Most of the extraction sites were owned by Lord Clifford, who lived at Ugbrooke House. The clay was taken to Hackney Clay Cellars for drying, and was then transferred to Teignmouth by packhorse, where it was loaded into coasters for delivery to the pottery industry. The situation was far from ideal, particularly as the Teignmouth moorings were tidal, and the high tidal range made loading difficult.[1]

In order to improve the situation, Lord Clifford built a canal to link the clay pits to the River Teign. Its terminus was close to the Newton Abbot to Kingsteignton road. The canal opened on 17 March 1843.[2] It was 0.6 miles (0.97 km) long, and had a single lock where it joined the river[3] that was 108 by 14 feet (32.9 by 4.3 m), with a depth of 3.75 feet (1.14 m) over the lower cill.[1] The wooden boats which sailed on the estuary were around 50 feet (15 m) long and 14 feet (4.3 m) wide, with a flat bottom, a rounded bow and a flat transom stern. They were fitted with a single square sail, like a Viking longboat, and in many respects were very similar to the Humber keels which plied the waterways of the north east of England.[4] The length of the lock enabled two boats to use it at the same time.[1]

In 1844 the South Devon Railway Company built a bridge over the canal, with the harbour commissioners of the port of Teignmouth retaining John Rennie to ensure that, among other things, the bridge over the canal was large enough to allow boat traffic to continue.[2]

In 1858, the Newton and Moretonhampstead Railway was authorised, although the company was reconstituted as the Moretonhampstead and South Devon Railway in 1861, before any work began. It was effectively owned by the South Devon Railway. The neighbouring Stover Canal negotiated with the company, and they bought out the canal for £8,000 in 1862. A month after the acquisition, the minutes recorded a letter from Watts, Blake and Company, who traded on that canal, asking what price they would be willing to sell the canal for, as they believed the directors intended to dispose of it. Although there is no record of the railway company buying the Hackney Canal, a letter was received at the same time from Mr Whiteway, acting on behalf of a Mr Knight who held the lease for the Hackney Canal, asking much the same question. The railway company agreed to notify both parties that no decisions had been made to dispose of their canal interests.[5]

Decline

The canal ceased to be used in 1928.[3] Since the terminus was next to a main road, the advent of the motor lorry resulted in its closure. The basin was briefly used by a company building yachts in 1954, but they resorted to sending the completed boats to Teignmouth by lorry, and moved to Brixham soon afterwards. A wall was constructed around the lock in 1955 after high tides in the estuary broke through and flooded Newton Abbot Racecourse.[6]

Route

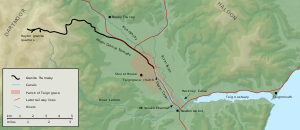

The terminus was close to the Kingsteignton road, and consisted of a basin with buildings on both sides. The basin was filled in to enable lorries to turn,[7] and the buildings were for many years used by A J Booker's Autobodies as a car body workshop.[8] Although they were grade II listed structures, all except one were demolished in 2001 as part of a redevelopment of the area.[9] The tow-path followed the north bank of the canal, and the water supply entered the canal from a leat which passed under the tow-path to the east of the wharf buildings,[7] crossing over a drainage ditch on an aqueduct before it did so. To the south of the wharf area was Newton Abbot Potteries, built before 1905, and labelled "Bricks and Pipes" on the 1956 map.[10] After a short distance, the canal turned to the south-east, and followed a nearly straight line across what is now the end of Newton Abbot racecourse. In 1969, the end of the racetrack followed the west bank of the canal,[11] but by 1989 the track had been extended across the site of the canal. A drainage ditch crosses the area, which gives an indication of where the canal was, since the ditch was on the west side of the canal before it was filled in.[12] Just beyond the second crossing by the race track are the remains of the lock and the wall which prevents the Teign flooding the area. The route turns to the east, to pass under the railway line, and joins the Hackney channel of the River Teign.[13]

Points of interest

| Point | Coordinates (Links to map resources) |

OS Grid Ref | Notes

a |

|---|---|---|---|

| Hackney Clay Cellars | 50.5429°N 3.5983°W | SX868726 | Northern terminus |

| Newton Abbot racecourse crossing | 50.5409°N 3.5950°W | SX870724 | North side |

| Site of lock | 50.5386°N 3.5919°W | SX872721 | |

| Junction with Hackney Channel | 50.5389°N 3.5888°W | SX875722 | River Teign |

Bibliography

- Ewans, M.C. (1966). The Haytor Granite Tramway and Stover Canal. Newton Abbot: David & Charles.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hadfield, Charles (1985). The Canals of Southwest England. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 0-7153-8645-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Harris, Richard (2010). "The Hackney Canal". Devon Heritage. Retrieved 28 February 2011.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

- Ewans 1966, p. 38

- Hadfield 1967, pp. 121–122

- Hadfield 1967, p. 190

- Ewans 1966, p. 35

- Ewans 1966, pp. 39–41

- Ewans 1966, p. 49

- Ewans 1966, p. 59

- Historic England. "Clay Cellars Kingsteighton (1165512)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

- Harris 2010, p. 3

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1905 and 1956

- Ordnance Survey, 1:10,560 map, 1969

- Ordnance Survey, 1:2500 map, 1956 and 1989

- Ewans 1966, p. 60