Canton of Grisons

The canton of (the) Grisons, or canton of Graubünden,[lower-alpha 1] is the largest and easternmost canton of Switzerland. It has international borders with Italy, Austria, and Liechtenstein. Its German name, Graubünden, translates as the "Grey Leagues", referring to the canton's origin in three local alliances, the League of God's House, the Grey League, and the League of the Ten Jurisdictions. Grisons is the only officially trilingual canton and the only one where the Romansh language has official status. Swiss German, Italian, and Romansh are all native to the canton.

Canton of Grisons | |

|---|---|

| Canton of Grisons | |

Coat of arms | |

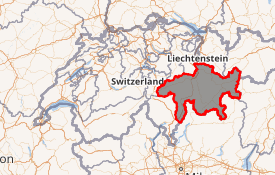

Location in Switzerland

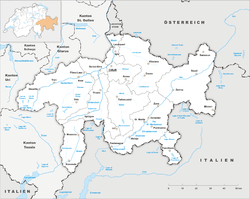

Map of Grisons  | |

| Coordinates: 46°45′N 9°30′E | |

| Capital | Chur |

| Subdivisions | 108 municipalities, 11 districts |

| Government | |

| • Executive | Executive Council (5) |

| • Legislative | Grand Council (120) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 7,105.39 km2 (2,743.41 sq mi) |

| Population (December 2018)[2] | |

| • Total | 198,379 |

| • Density | 28/km2 (72/sq mi) |

| ISO 3166 code | CH-GR |

| Highest point | 4,049 m (13,284 ft): Piz Bernina |

| Lowest point | 260 m (853 ft): border to Ticino at San Vittore |

| Joined | 1803 |

| Languages | German, Italian, Romansh |

| Website | www |

Geography and climate

Grisons is Switzerland's largest canton by area at 7,105.2 square kilometres (2,743.3 sq mi), 19.2% larger than the Canton of Bern.[3] Only about a third of this is commonly regarded as productive land of which forests cover about a fifth of the total area.[3] The canton is entirely mountainous, comprising a 3-fold water divide with the highlands of the Rhine, Inn/ Danube and Moesa/ Ticino / Po river valleys. In its southeastern part lies the only official Swiss National Park. In its northern part the mountains were formed as part of the thrust fault that was in 2008 declared a geologic UNESCO World Heritage Site, under the name Swiss Tectonic Arena Sardona. Another Biosphere Reserve is the Biosfera Val Müstair adjacent to the Swiss National Park, while Ela Nature Park is one of the regionally supported parks.

Elevations in the Grison Alps include Tödi, at 3,614 metres (11,857 ft), and the highest peak, Piz Bernina, at 4,049 metres (13,284 ft). Many of the mountain ranges feature extensive glaciers, such as at the Adula, the Albula, the Silvretta, the Bernina, the Bregaglia and the Rätikon ranges. The mountain ranges in the central area are very steep, having some of the deepest valleys in Europe. These valleys were originally settled by the Raetians (Rhaeti).

Grisons borders on the cantons of St. Gallen to the north, Glarus to the north-west, Uri to the west, and Ticino to the south-west. The capital city is Chur. The world-famous resorts of St. Moritz and Davos-Klosters are located in the canton, complemented by the larger all-year-round tourist destinations of Arosa, Flims, Lenzerheide, Scuol-Sammnaun and more.[4]

The climate is arid-dry as Graubünden is shielded on all sides from rain.[5]

History

Most of the lands of the canton were once part of a Roman province called Raetia, which was established in 15 BC. The current capital of Grisons, Chur, was known as Curia in Roman times. The area later was part of the lands of the diocese of Chur.

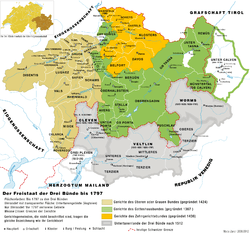

In 1367 the League of God's House (Cadi, Gottes Haus, Ca' di Dio) was founded to resist the rising power of the Bishop of Chur. This was followed by the establishment of the Grey League (Grauer Bund), sometimes called Oberbund, in 1395 in the Upper Rhine valley. The name Grey League is derived from the homespun grey clothes worn by the people and was used exclusively after 16 March 1424.[6] The name of this league later gave its name to the canton of Grisons. A third league was established in 1436 by the people of ten bailiwicks in the former Toggenburg countship, as the dynasty of Toggenburg had become extinct. The league was called League of the Ten Jurisdictions (Zehngerichtebund).

The first step towards the canton of Grisons was when the league of the Ten Jurisdictions allied with the League of God's House in 1450. In 1471 the two leagues allied with the Grey League. In 1497 and 1498 the Leagues[7] allied with the Old Swiss Confederacy after the Habsburgs acquired the possessions of the extinct Toggenburg dynasty in 1496,[8] siding with the Confederacy in the Swabian War three years later. The Habsburgs were defeated at Calven Gorge and Dornach, helping the Swiss Confederation and the allied leagues of the canton of Grisons to be recognised. However the Three Leagues remained a loose association until the Bundesbrief of 23 September 1524.[9]

The last traces of the Bishop of Chur's jurisdiction were abolished in 1526. The Musso war of 1520 drove the Three Leagues closer to the Swiss Confederacy.

Between 1618 and 1639 it became a battleground between competing factions during the Bündner Wirren. The Protestant party was supported by France and Venice, while the Catholic party was supported by the Habsburgs in Spain and Austria. Each side sought to gain control of the Grisons to gain control over the important alpine passes. In 1618, the young radical Jörg Jenatsch became a member of the court of 'clerical overseers' and a leader of the anti-Habsburg faction. He supervised the torture to death of the arch-priest Nicola Rusca of Sondrio. In response, Giacomo Robustelli of the pro-Catholic Planta family, raised an army of rebels in the Valtellina. On the evening of 18/19 July 1620, a force of Valtellina rebels supported by Austrian and Italian troops marched into Tirano and began killing Protestants. When they finished in Tirano, they marched to Teglio, Sondrio and further down the valley killing every Protestant that they found. Between 500[10] and 600[11] people were killed on that night and in the following four days. The attack drove nearly all the Protestants out of the valley, prevented further Protestant incursions and took the Valtellina out of the Three Leagues.

In response, in February 1621, Jenatsch led a force of anti-Habsburg troops to attack Rietberg Castle, the home of a leader of the pro-Catholic faction, Pompeius Planta.[12] They surprised Planta and according to legend he was killed by Jörg Jenatsch with an axe.[13] The murder of Planta encouraged the Protestant faction and they assembled a poorly led and disorganized army to retake the Valtellina and other subject lands. However, the army fell apart before they could attack a single Catholic town.[12] This Protestant invasion provided the Spanish and Austrians an excuse to invade the Leagues. By the end of October, Spain and Austria had occupied all of Grisons. The resulting peace treaty of January 1622, forced Grisons to cede the Müstair, the Lower Engadine and Prättigau valleys.[10] The treaty also forbade the Protestant religion in these valleys. In response, in 1622, the Prättigau valley rebelled against the Austrians and drove them out of the valley. The Austrians invaded the valley twice more, attempting to reimpose the Catholic faith, in 1623–24 and 1629–31.[14]

In 1623 the Leagues entered into an alliance with France, Savoy and Venice. Jürg Jenatsch and Ulysses von Salis used French money to hire an 8,000-man mercenary army and drive out the Austrians. The peace treaty of Monzon (5 March 1626) between France and Spain, confirmed the political and religious independence of the Valtellina. In 1627 the French withdrew from the Valtellina valley, which was then occupied by Papal troops. Starting in 1631 the League, under the French Duke Henri de Rohan, started to expel the Spaniards. However, Richelieu still did not want to hand the valley over to its residents. When it became clear that the French intended to remain permanently in the Leagues, but would not force the Valtellina to convert to Protestantism, Jürg Jenatsch (now a mercenary leader) converted in 1635 to the Catholic faith. In 1637, he rebelled and allied with Austria and Spain. His rebellion along with the rebellion of 31 other League officers forced the French to withdraw without a fight.[10][14] On 24 January 1639, Jürg Jenatsch was killed during Carnival by an unknown attacker who was dressed as a bear. The attacker may have been a son of Pompeius Planta[10] or an assassin hired by the local aristocracy.[14] According to legend he was killed by the same axe that he used on Pompeius Planta.[13] On 3 September 1639 the Leagues agreed with Spain to bring the Valtellina back under League sovereignty, but with the promise to respect the free exercise of the Catholic faith. Treaties with Austria in 1649 and 1652, brought the Müstair and Lower Engadine valleys back under the authority of the Three Leagues.[10]

In 1798, the lands of the canton of Grisons became part of the Helvetic Republic as the Canton of Raetia except Valtellina, which was separated in 1797 for joining to the Cisalpine Republic. It was later part of Empire of Austria in 1814 before joining to Kingdom of Italy in 1859. With the Act of Mediation the "perpetual ally" of Switzerland became a canton in 1803. The constitution of the canton dates from 1892. In the following century, there have been about 30 changes made to the constitution.[15]

The arms of the three original leagues were combined into the modern cantonal coat of arms in 1933.

Government

The Grand Council (German: Grosser Rat; Italian: Gran Consiglio, Romansh: Cussegl Grond), the legislature of the canton, sits in Chur, the cantonal capital. Its 120 members, elected in 39 districts using a majority system, are in office for four years. The last district elections were in 2014.[16] The cantonal government, exercising executive authority, is made up of five members, elected by the parliament for a term of four years and limited to two terms. The current President of Government is Hansjörg Trachsel.[17]

The constitution of Grisons, last revised on 14 September 2003, states in its preamble that the canton's purpose is to "safeguard freedom, peace, and human dignity, ensure democracy and the Rechtsstaat, promote prosperity and social justice and preserving a sane environment for the future generations, with the intention of promoting trilingualism and cultural variety and conserving them as part of our historical heritage".[18]

The constitution allows for the enfranchisement of foreign residents at a municipal level, at discretion of the local governments. In 2009, the municipality of Bregaglia became the first in the canton to make use of this provision, granting voting rights to foreigners.[19]

Politics

Federal election results

| Percentage of the total vote per party in the canton in the Federal Elections 1971-2015[20] | ||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Party | Ideology | 1971 | 1975 | 1979 | 1983 | 1987 | 1991 | 1995 | 1999 | 2003 | 2007 | 2011 | 2015 | |

| FDP.The Liberalsa | Classical liberalism | 14.8 | 18.1 | 22.9 | 20.1 | 18.3 | 18.1 | 16.5 | 15.1 | 15.8 | 19.1 | 11.9 | 13.3 | |

| CVP/PDC/PPD/PCD | Christian democracy | 37.3 | 35.9 | 35.5 | 33.3 | 28.5 | 25.6 | 26.9 | 25.6 | 23.7 | 20.3 | 16.6 | 16.8 | |

| SP/PS | Social democracy | 13.9 | 15.2 | 20.5 | 24.6 | 19.5 | 21.2 | 21.6 | 26.6 | 24.9 | 23.7 | 15.6 | 17.6 | |

| SVP/UDC | Swiss nationalism | 34.0 | 26.9 | 21.1 | 22.0 | 20.0 | 19.5 | 26.9 | 27.0 | 33.8 | 34.7 | 24.5 | 29.7 | |

| Ring of Independents | Social liberalism | * b | * | * | * | * | * | 1.1 | * | * | * | * | * | |

| CSP/PCS | Christian left | * | * | * | * | * | 6.9 | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| GLP/PVL | Green liberalism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 8.3 | 7.9 | |

| BDP/PBD | Conservatism | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 20.5 | 14.5 | |

| GPS/PES | Green politics | * | * | * | * | * | * | 3.5 | * | * | * | 2.2 | * | |

| FGA | Feminist | * | * | * | * | 6.0 | 4.3 | 1.9 | * | * | * | * | * | |

| SD/DS | National conservatism | * | 3.5 | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | |

| EDU/UDF | Christian right | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | * | 1.9 | 1.6 | 0.5 | * | |

| Other | * | 0.3 | * | * | 7.7 | 4.4 | 1.7 | 5.8 | * | 0.6 | * | 0.2 | ||

| Voter participation % | 56.7 | 49.6 | 45.9 | 39.9 | 39.5 | 37.9 | 36.7 | 40.6 | 39.1 | 41.9 | 45.1 | 46.0 | ||

Political subdivisions

Regions

as of January 2017[21]

- Albula with capital Tiefencastel

- Bernina with capital Poschiavo

- Engiadina Bassa/Val Müstair with capital Scuol

- Imboden with capital Domat/Ems

- Landquart with capital Igis

- Maloja with capital Samedan

- Moesa with capital Roveredo

- Plessur with capital Chur

- Prättigau/Davos with capital Davos

- Surselva with capital Ilanz

- Viamala Region with capital Thusis

Municipalities

There are 114 municipalities in the canton (as of January 2016).[22]

Demographics

The inhabitants of Grisons are called Bündner or (rarely) Grisonians.

The population of the canton (as of 31 December 2018) is 198,379.[2] As of 2007, the population included 28,008 foreigners, or about 14.84% of the total population.[23] The main religions are Catholicism and Protestantism. Both are well represented in the canton, with Roman Catholics forming a slight plurality (47% Catholic to 41% Protestant).[24]

Languages

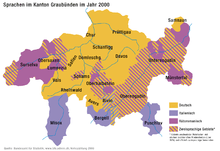

Grisons is the only canton of Switzerland with three official languages: German in the northwest (64%), Romansh in the Engadin and around Disentis/Mustér (13%), and Italian in the Italian Grisons (11%) with the remaining 13% speaking another language as their mother language.[25]

| Year | Population | Romansh (%) | German (%) | Italian (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1803 | 73,200[28] | 36,700 (~50%) | 26,500 (~36%) | 10,000 (~14%) |

| 1850 | 89,895 | 42,439 (47.2%) | 39.5% | 13.3% |

| 1880 | 93,864 | 37,794 (39.8%) | 43,664 (46.0%) | 12,976 (13.7%) |

| 1900 | 104,520 | 36,472 (34.9%) | 48,762 (46.7%) | 17,539 (16.8%) |

| 1920 | 119,854 | 39,127 (32.7%) | 61,379 (51.2%) | 17,674 (14.8%) |

| 1941 | 128,247 | 40,187 (31.3%) | 70,421 (54.9%) | 16,438 (12.8%) |

| 1950 | 137,100 | 40,109 (29.3%) | 77,096 (56.2%) | 18,079 (13.2%) |

| 1960 | 147,458 | 38,414 (26.1%) | 83,544 (56.7%) | 23,682 (16.1%) |

| 1970 | 162,086 | 37,878 (23.4%) | 93,359 (57.6%) | 25,575 (15.8%) |

| 1980 | 164,641 | 36,017 (21.9%) | 98,645 (59.9%) | 22,199 (13.5%) |

| 2000 | 187,058 | 27,038 (14.5%) | 127,755 (68.3%) | 19,106 (10.2%) |

| 2012 | 191,612 | 27,955 (15.2%) | 143,015 (74.6%) | 23,506 (12.0%) |

| 2015[29] | 193,662 | 29,826 (15.4%) | 142,378 (73.5%) | 25,033 (12.9%) |

Romansh is an umbrella term for a group of closely related dialects, spoken in southern Switzerland, with all belonging to the Rhaeto-Romance language family. These dialects include Sursilvan, Sutsilvan, Surmiran, Puter and Vallader. Romansh was nationally standardised in 1982 by Zürich-based linguist Heinrich Schmid. The standardised language, called Rumantsch Grischun, has been slowly accepted. Romansh has been recognized as one of four "national languages" by the Swiss Federal Constitution since 1938. It was declared an "official language" of the Confederation in 1996, meaning that Romansh speakers may use Rumantsch Grischun for correspondence with the federal government and expect to receive a response in the same language. Romansh has official language status at the canton level. Municipalities in turn are free to specify their own official languages. Before the introduction of the official written form of Rumantsch Grischuni in 2003, books for students in public schools were printed in the five different idioms throughout the state.

Economy

Agriculture is still essential to keep remote valleys inhabited and cultivated, differing it from sheer wilderness. Agriculture is therefore supported by subsidies by the authorities both national and regional. Eight percent of the population work in agriculture and forestry, where 50 per cent of the production is certified as organic. Agriculture includes forests and mountain pasturage in summer, particularly of cows, sheep and goats. Since wolf and bear have returned, the use of Maremma Sheepdogs is not unusual.[5]

There is wine production in the Rhine Valley north to the capital Chur. 24 per cent of the workforce are employed in industry whereas 68 per cent work in the service industry where tourism reaches a remarkable 14 per cent of the GDP. Tourism is concentrated around the towns of Davos/Arosa, Flims and St. Moritz/Pontresina. There are, however, a great number of other tourist resorts in the canton, divided by the official tourist board for winter sports for example into categories "Top - Large - Small and beautiful" [30] St. Moritz is said to be the cradle of winter tourism at all around 1860.

The Chur area is also an industrial centre. In the southern valleys of Mesolcina and Poschiavo there is corn (maize) and chestnut farming.

Transport

Transport has always been an important issue in the area; cart tracks from the Roman era were found on Julierpass and Septimerpass was rebuilt for cart use in 1387 and, although it later became unimportant, it is still in its 1800 form (for hikers only). Corniche paths were necessary for long stretches, and gorges such as the Viamala gave construction problems for any kind of transport. The first real roads of 3.7 m (4 yd) width were built across the Alps from around 1816, one of which is still in a very good historical condition[31] as this connection across Splügen Pass lost its importance after the opening of rail tunnels crossing the alps. The last valley to be connected to the road system in the state of Grisons was Avers, whose remote hamlet of Juf was only reached in 1897. Eventually, the inhabitants of Grisons gave up their resistance against individual motor traffic in 1926,[32] and the 1967 opened San Bernardino road tunnel, built to host tourism traffic, is used also by heavy goods vehicles nowadays although not really suitable for them for its ascent gradients. Most other passes have lost their importance for goods transport nowadays. Huge efforts ensure public transport to (nearly) every settlement by an integrated timetable of postbuses and the Rhaetian Railway, the largest narrow-gauge railway network in Switzerland, in which the cantonal government is the largest shareholder. Even Juf, inhabited by some 30 people only but holding a European record, is reached 5 times a day by public transport. The Swiss Federal Railways extend only a few kilometres into the canton, to the capital, Chur, where passengers transfer to the Rhaetian Railway. "Rhaetia" is the Latin name for the area. The Albula Line became a UNESCO world heritage as did the Bernina Railway, the highest and only railway to cross the alps without the use of a tunnel at the pass. In winter some of the road passes are closed [33] whereas several high mountain passes such as the Julier, Bernina and Lukmanier are kept open all winter (subject to restrictions). Being the highest elevated state in Switzerland, Grisons hosts huge alpine areas that are not accessible by any means of transport but have to be walked to.[34] The Engiadin valley has its own airport, Samedan Airport.

Culture

The canton has a large concentration of medieval castles (and ruins). Many such examples are found in the Domleschg area. Close by lies the church of Zillis, where 1130/40 a famous romanesque illustrated ceiling was added which is now treated as national heritage. Three World Heritage Sites are located in the canton: the Benedictine Convent of Saint John, the Swiss Tectonic Arena Sardona and the Rhaetian Railway in the Albula and Bernina Landscapes.

The Grisons are known for a dried-beef delicacy called Bündnerfleisch and for a nut and honey pie known as Bündner Nusstorte. Another specialty, predominantly made in the western part of Grison, are Capuns,[35] hearty dumplings with pieces of meat wrapped in chard leaves.

The Raetia national football team, a member of the NF-Board, represents the region at international level, and competed in the 2012 VIVA World Cup.

Nature

Graubünden successfully reintroduced ibex in the early 20th century after it had all but died out from the Alps, except for an area in the Aosta Valley in Italy, Parco Nazionale Gran Paradiso.[36] Similarly, it reintroduced the bearded vulture and lynx in the 21st century, which had been extinguished, though the lynx remains rare.[37]

See also

Notes and references

-

- German: Kanton Graubünden, Swiss Standard German: [ɡraʊˈbʏndn̩] (

- Romansh: chantun Grischun [ɡʁiˈʒun] (

- Italian: Cantone dei Grigioni [ɡriˈdʒoːni]

- French: canton des Grisons [ɡʁizɔ̃]

- German: Kanton Graubünden, Swiss Standard German: [ɡraʊˈbʏndn̩] (

- Arealstatistik Land Cover - Kantone und Grossregionen nach 6 Hauptbereichen accessed 27 October 2017

- Swiss Federal Statistical Office - STAT-TAB, online database – Ständige und nichtständige Wohnbevölkerung nach institutionellen Gliederungen, Geburtsort und Staatsangehörigkeit (in German) accessed 23 September 2019

- Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Regional Statistics for Graubünden". Archived from the original on 14 April 2009. Retrieved 23 November 2008.

- "Destinations on official tourism board Graubünden, Switzerland holiday destinations". Archived from the original on 16 January 2011. Retrieved 17 January 2011.

- Mayer, Kurt (3 August 2015). Das Engadin – Naturwunder der Alpen (documenatry) (in German).

- Grauer Bund in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Eidgenossenschaft - Konsolidierung und Erweiterung (1353-1515) in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Graubünden, section 3.1.4 - Landesherrschaft und Widerstand im Norden in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Graubünden, section 3.2.4 - Verfassung und Landesgesetze in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Swiss History (in German) accessed 16 January 2012

- Valtellina murders in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Graubünden's religious history (PDF; 3.95 MB) (in German)

- MacNamee, Terence (17 April 2012). "DNA tests aim to identify 17th century figure". Swissinfo.com. Retrieved 20 April 2012.

- Bündner Wirren in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- Graubünden, section 4.2.2-Von 1848 bis heute in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- ""Der Grosse Rat" Parliament of the Canton Grisons". Portal of the Canton Grisons. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Government of the Canton Grisons". Portal of the Canton Grisons. Archived from the original on 3 June 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Constitution of the canton of Graubünden" (in Italian and German). Federal Authorities of the Swiss Confederation. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- "Comune Bregaglia accorda diritto di voto e di eleggibilità a stranieri domiciliati" (in Italian). swissinfo. 17 May 2009. Retrieved 8 July 2009.

- Nationalratswahlen: Stärke der Parteien nach Kantonen (Schweiz = 100%) (Report). Swiss Federal Statistical Office. 2015. Archived from the original on 2 August 2016. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- Federal Statistical Office

- "Répertoire officiel des communes de Suisse". Statistique Suisse. 1 January 2009. Archived from the original on 12 June 2009. Retrieved 10 July 2009.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Staatsangehörigkeit, Geschlecht und Kantonen". Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 15 December 2008. Retrieved 5 November 2008.

- Federal Department of Statistics (2008). "Wohnbevölkerung nach Religion, nach Kantonen und Städten". Archived from the original (Microsoft Excel) on 29 December 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2008.

- (in German and Italian) Canton of Graubünden Website accessed 8 November 2017

- Coray, Renata (2008), Von der Mumma Romontscha zum Retortenbaby Rumantsch Grischun: Rätoromanische Sprachmythen (in tedesco), Chur: Institut für Kulturforschung Graubünden ikg, ISBN 978-3-905342-43-7, p. 86

- Canton Grigioni in German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.

- "Die ersten Volkszählungen in Graubünden" (PDF).

- Federal Statistical Office - Ständige Wohnbevölkerung nach Hauptsprachen und Kanton, 2015 accessed 8 November 2017

- Switzerland holidays Graubünden winter

- (in English) Historic route across Alps Splügen Pass hike in Switzerland Archived 6 July 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- (in English) Facts for Graubünden Switzerland Archived 14 April 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- (in German) statistical pass closures in Graubünden

- (in English) Hike the alps in Switzerland; Information, Graubünden Archived 15 May 2011 at the Wayback Machine

- "Capuns recipe". Archived from the original on 1 September 2009. Retrieved 17 August 2008.

- Stüwe, M., Nievergelt, B. (1991). "Recovery of Alpine ibex from near extinction: the result of effective protection, captive breeding, and reintroductions". Applied Animal Behaviour Science. 29 (1–4): 379–387. doi:10.1016/0168-1591(91)90262-V.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Reintroduction". Foundation for the Bearded Vulture www.beardedvulture.ch. n.d. Retrieved 6 April 2020.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Canton of Graubünden (Grisons). |

- Official Canton website

- Canton of Graubünden Tourism website

- Official Canton of Graubünden statistics website

- Canton of Grisons in Romansh, German, French and Italian in the online Historical Dictionary of Switzerland.