Google Arts & Culture

Google Arts & Culture (formerly Google Art Project) is an online platform through which the public can view high-resolution images and videos of artworks and cultural artifacts from partner cultural organizations throughout the world.

| |

Screenshot of the website, showing different themes. | |

| Developer(s) | Google Cultural Institute Google Inc. |

|---|---|

| Initial release | February 1, 2011 |

| Website | artsandculture |

The digital platform utilizes high-resolution image technology that enables the public to virtually tour partner organization collections and galleries and explore the artworks' physical and contextual information. The platform includes advanced search capabilities and educational tools,[1] .

Site components

Features of first-generation Google Arts & Culture

Virtual Gallery Tour

- Through the Virtual Gallery Tour (aka Gallery View) users can virtually ‘walk through’ the galleries of each partner cultural organization, using the same controls as Google Street View or by clicking on the gallery’s floorplan.

Artwork View

- From the Gallery View (aka Microscope View), users could zoom in on a particular artwork to view the picture in greater detail. As of April 2012, over 32,000 high-quality images were available. The Microscope view provided users a dynamic image of an artwork and scholarly and contextual information to enhance their understanding of the work. When examining an artwork, users could also access information on the item's physical characteristics (e.g. size, material(s), artist). Additional options were Viewing Notes, History of the Artwork, and Artist Information, which users can easily access from the microscope view interface. Each cultural organization was allowed to include as much material as they wanted to contribute, so the level of information varied.[2]

Create an Artwork Collection

- Users could compile any number of images from the partner organizations and save specific views of artworks to create a personalized virtual exhibition. Using Google’s link abbreviator (Goo.gl), users could share their artwork collection with others through social media and conventional online communication mechanisms. This feature was so successful upon the platform’s launch that Google had to dedicate additional servers to support it.[3] The second-generation platform integrated Google's social media platform Google+, so that site users could upload video and audio content to personalize their gallery and share their own collections through social media.[4]

Features of second-generation Google Arts & Culture

Explore and Discover

- In the second launch of the platform, Google updated the platform's search capabilities so that users could more easily and intuitively find artworks. Users could find art by filtering their search with several categories, including: artist, museum, type of work, date, and country. The search results were displayed in a slideshow format.[1] This new function enabled site users to more easily search across numerous collections.

Video and Audio Content

- Several partner cultural organizations opted to include guided tours or welcome videos of their galleries. This provided users the option to virtually walk through a museum and listen to an audio guide for certain artworks, or to follow a video tour that guided them through a gallery. For example, Michelle Obama filmed a welcome video for the White House gallery page,[5] and Israel's Holocaust Museum Yad Vashem launched a YouTube channel with 400 hours of original video footage from the trial of Adolf Eichmann which users could access through the museum's Arts & Culture exhibits.[6]

Education

- Google Arts & Culture includes several educational tools and resources for teachers and students, such as educational videos, art history timelines, art toolkits, and comparative teaching resources.[7]. Two features, called "Look Like an Expert" and "DIY", provide activities similar to those often found in art galleries. For example, one quiz asks site visitors to match a painting to a particular style; another asks visitors to find a symbol within a specified painting that represents a provided story.

Development

The platform emerged as a result of Google's "20-percent time" policy, by which employees were encouraged to spend 20% of their time working on an innovative project of interest.[11] A small team of employees created the concept for the platform after a discussion on how to use the firm's technology to make museum’ artwork more accessible.[12] The platform concept fit the firm's mission "to organize the world’s information and make it universally accessible and useful."[13] Accordingly, in mid-2009, Google executives agreed to support the project, and they engaged online curators of numerous museums to commit to the initiative.[14]

The platform was launched on February 1, 2011 by the Google Cultural Institute with contributions from international museums, including the Tate Gallery, London, the Metropolitan Museum of Art. New York City; and the Uffizi, Florence.[15] On April 3, 2012, Google announced a major expansion, with more than 34,000 artworks from 151 museums and arts organizations from 40 countries, including the Art Gallery of Ontario, the White House, the Australian Rock Art Gallery at Griffith University, the Museum of Islamic Art, Doha, and the Hong Kong Museum of Art.[16]

Technology used

The team leveraged existing technologies, including Google Street View and Picasa, and built new tools specifically for the platform.

They created an indoor-version of the Google Street View 360-degree camera system to capture gallery images by pushing the camera 'trolley' through a museum. It also used professional panoramic heads Clauss Rodeon VR Head Hd And Clauss VR Head ST to take high-resolution photos of the artworks within a gallery. This technology allowed the excellent attention to detail and the highest image resolution. Each partner museum selected one artwork to be captured at ultra-high resolution with approximately 1,000 times more detail than the average digital camera.[2] The largest image, Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov's The Apparition of Christ to the People, is over 12 gigapixels. To maximize image quality, the team coordinated with partner museums’ lighting technicians and photography teams. For example, at the Tate Britain, they collaborated to capture a gigapixel image of No Woman No Cry in both natural light and in the dark. The Tate suggested this method to capture the painting's hidden phosphorescent image, which glows in the dark. The Google camera team had to adapt their method and keep the camera shutter open for 8 seconds in the dark to capture a distinct enough image. Now, unlike at the Tate, from the site, one can view the painting in both light settings.[17]

Once the images were captured, the team used Google Street View software and GPS data to seamlessly stitch the images and connect them to museum floor plans. Each image was mapped according to longitude and latitude, so that users can seamlessly transition to it from Google Maps, looking inside the partner museums’ galleries. Street View was also integrated with Picasa, for a seamless transition from gallery view to microscope view.[12]

The user interface lets site visitors virtually ‘walk through’ galleries with Google Street View, and look at artworks with Picasa, which provides the microscope view to zoom in to images for greater detail than is visible to the naked eye.[2] Additionally, the microscope view of artworks incorporates other resources—including Google Scholar, Google Docs and YouTube—so users can link to external content to learn more about the work.[18] Finally, the platform incorporates Google's URL shortener (Goo.gl), so that users can save and easily share their personal collections.[18]

The platform has been integrated with the social media platform Google+ to enable users to share their personal collections with their networks. This integration also lets site visitors use Google+ Hangouts for more interactive purposes. These situations might include: a professor giving an online lecture to students, engaging in video and shared-screen discussions about a collection, or an expert leading a virtual tour of a distant museum to remote attendees.[4]

The resulting platform is a Java-based Google App Engine Web application, which exists on Google's infrastructure.[18]

Technology limitations

Luc Vincent, director of engineering at Google and head of the team responsible for Street View for the platform, stated concern over the quality of panorama cameras his team used to capture gallery and artwork images. In particular, he believes that improved aperture control would enable more consistent quality of gallery images.[2]

Some artworks were particularly difficult to capture and re-present accurately as virtual, two-dimensional images. For example, Google described the inclusion of Hans Holbein the Younger's The Ambassadors as "tough". This was due to the anamorphic techniques distorting the image of a skull in the foreground of the painting. When looking at the original painting at the National Gallery in London, the depiction of the skull appears distorted until the viewer physically steps to the side of the painting. Once the viewer is looking at the shape from the intended vantage point, the lifelike depiction of the skull materializes. The effect is still apparent in the gigapixel version of the painting, but was less pronounced in the "walk-through" function.[19]

As New York Times art reviewer Roberta Smith said: “[Google Arts & Culture] is very much a work in progress, full of bugs and information gaps, and sometimes blurry, careering virtual tours.”[2] Though the second-generation platform solved some technological issues, the firm plans to continue developing additional enhancements for the site. Future improvements currently under consideration include: upgrading panorama cameras, more detailed web metrics, and improved searchability through meta-tagging and user-generated meta-tagging.[3] The firm is also considering the addition of an experimental page to the platform, to highlight emerging technologies that artists are using to showcase their works.[20]

Institutions and works

Seventeen partner museums were included in the launch of the project. The original 1,061 high-resolution images (by 486 different artists) are shown in 385 virtual gallery rooms, with 6,000 Street View–style panoramas.[19][21]

List of the initial 17 partner museums

Below is a list of the original seventeen partner museums at the time of the platform's launch. All images shown are actual images from Google Arts & Culture:

| Partner Museum | Gigapixel artwork | Title | Artist | Date |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin, Germany |  | In the Conservatory | Édouard Manet | 1878–1879 |

| Freer Gallery of Art, Smithsonian Washington, DC, USA |  | The Princess from the Land of Porcelain | James McNeill Whistler | 1863–1865 |

| Frick Collection New York, USA |  | St Francis in the Desert | Giovanni Bellini | c. 1480 |

| Gemäldegalerie Berlin, Germany |  | The Merchant Georg Gisze | Hans Holbein the Younger | 1497–1562 |

| Museum Kampa Prague, Czech Republic |  | The Cathedral (Katedrála) | František Kupka | 1912–1913 |

| Metropolitan Museum of Art New York, USA |  | The Harvesters | Pieter Bruegel the Elder | 1565 |

| Museum of Modern Art New York, USA |  | The Starry Night | Vincent van Gogh | 1889 |

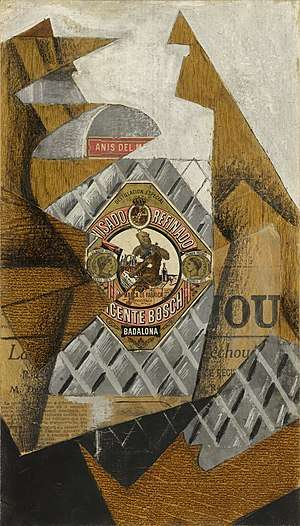

| Museo Reina Sofia Madrid, Spain |  | The Bottle of Anís del Mono | Juan Gris | 1914 |

| Thyssen-Bornemisza Museum Madrid, Spain |  | Young Knight in a Landscape | Vittore Carpaccio | 1510 |

| National Gallery London, UK |  | The Ambassadors | Hans Holbein the Younger | 1533 |

| Palace of Versailles Versailles, France |  | Marie-Antoinette de Lorraine-Habsbourg, Queen of France, and her children | Louise Élisabeth Vigée Le Brun | 1787 |

| Rijksmuseum Amsterdam Amsterdam, Netherlands |  | Night Watch | Rembrandt Harmensz. van Rijn | 1642 |

| State Hermitage Museum St. Petersburg, Russia |  | The Return of the Prodigal Son | Rembrandt Harmensz van Rijn | 1663–1665 |

| State Tretyakov Gallery Moscow, Russia | _-_Google_Art_Project.jpg) | The Appearance of Christ Before the People | Alexander Andreyevich Ivanov | 1837–1857 |

| Tate Britain London, UK | No Woman No Cry | Chris Ofili | 1998 | |

| Uffizi Florence, Italy |  | The Birth of Venus | Sandro Botticelli | 1483–1485 |

| Capitoline Museums Rome, Italy |  | Capitoline Wolf | 500 BC–480 BC | |

| Van Gogh Museum Amsterdam, Netherlands |  | The Bedroom | Vincent van Gogh | 1888 |

On April 3, 2012, Google announced the expansion of the platform to include 151 cultural organizations, with new partners contributing a gigapixel image of one of their works.[1]

Partial list of Google Cultural Institute partners

- ABURY Foundation Deutschland, Buffalo, New York

- Albright–Knox Art Gallery

- Alte Nationalgalerie Berlin

- Altes Museum Berlin

- Archäologisches Museum Hamburg

- Auswärtiges Amt

- Bavaria Film

- Bayerische Staatsbibliothek

- Berliner Philharmoniker

- Bildergalerie, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg

- British Library

- Bundesarchiv

- Federal Ministry of Education and Research (Germany)

- Burgtheater

- Collection Regard

- DEFA-Stiftung

- Deutsche Oper Berlin

- Deutsche Staatsoper Berlin

- Deutsches Hutmuseum Lindenberg

- Deutsches Meeresmuseum, Stiftung Deutsches Meeresmuseum

- Deutsches Museum

- Digital Bab al-Yeme (Freie Universität Berlin)

- East Side Gallery

- Eisensteins Universum, Filmwissenschaft Johannes Gutenberg-Universität Mainz

- Elbphilharmonie

- Embassy of the United States Bern

- Europeana

- Sammlung Essl

- Franz Marc Museum - Kunst im 20. Jahrhundert

- Freud Museum, London

- Frogs & Friends

- Galerie Alte und Neue Meister, Staatliches Museum Schwerin / Ludwigslust / Güstrow

- Galerie Neue Meister, Dresden

- Gemäldegalerie Alte Meister, Dresden

- Gemäldegalerie, Berlin

- Graffiti Lobby Berlin

- Grünes Gewölbe, Dresden

- Heinz Nixdorf Museums

- Hochschule Luzern – Design & Kunst

- Jenisch Haus, Historische Museen Hamburg

- Jüdisches Museum Berlin

- Jüdisches Museum Frankfurt / Museum Judengasse

- Jüdisches Museum Wien

- Kaiserliche Schatzkammer, Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien

- Kaiserliche Wagenburg Wien

- Khalili Collections

- Konferenz Nationaler Kultureinrichtungen

- Konzerthaus Berlin

- Kunstbibliothek, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Kunstgewerbemuseum, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Kupferstich-Kabinett, Dresden

- Kupferstichkabinett, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin

- Landesarchiv Nordrhein-Westfalen

- Landesmuseum für Kunst und Kulturgeschichte Oldenburg

- Leibniz-Gemeinschaft

- Lette Verein Berlin

- Lettl - Sammlung surreale Kunst

- MAK – Österreichisches Museum für angewandte Kunst / Gegenwartskunst

- Mathematisch-Physikalischer Salon, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Münzkabinett, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Museen Böttcherstraße

- Museen der Stadt Nürnberg

- Museum der Geschichte Polens, Berlin

- Museum Europäischer Kulturen, Berlin

- Museum Folkwang

- Museum für Hamburgische Geschichte

- Natural History Museum of Berlin

- Museum of Natural Sciences, Brussels

- Museum für Pferdestärken, Historisches Museum Basel

- Museum für Sächsische Volkskunst mit Puppentheatersammlung, Dresden

- Museum of Ethnology, Hamburg

- National Hispanic Cultural Center

- Natural History Museum, Vienna

- Neue Kammern, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten

- Austrian National Library

- Ozeaneum, Stiftung Deutsches Meeresmuseum

- Park Sanssouci, Stiftung Preußische Schlösser und Gärten Berlin-Brandenburg

- Pergamonmuseum, Berlin

- Polnisches Institut Berlin

- Pommersches Landesmuseum

- Porzellansammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Public Art in Public Places Project, California, United States

- Renaissance und Reformation. Deutsche Kunst im Zeitalter von Dürer und Cranach

- Rheingau Musik Festival]]

- Robert Havemann Gesellschaft

- Ruskin Library

- Rüstkammer, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Schloss Sanssouci

- Schloß Schönbrunn

- Schmuckmuseum Pforzheim

- Senckenberg Forschungsinstitut und Naturmuseum Frankfurt am Main

- Sigmund Freud Museum, Vienna

- Skulpturensammlung, Staatliche Kunstsammlungen Dresden

- Speicherstadt Hamburg

- Staatliche Ethnographische Sammlungen Sachsen, Dresden

- Staatliches Naturhistorisches Museum, Braunschweig

- Staatskanzlei des Saarlandes

- Stadtmuseum Marienbad

- Städtische Galerie im Lenbachhaus und Kunstbau

- Stiftung Brandenburger Tor im Max Liebermann Haus

- Stiftung für Kunst und Kultur

- Technoseum - Landesmuseum für Technik und Arbeit in Mannheim

- Textilmuseum St. Gallen

- TextilTechnikum

- Trinity College Library

- Urban Art Now

- VDMD – Netzwerk Deutscher Mode- und Textil-Designer

- Widewalls Collection

- Wien Museum

- Wiener Staatsoper

- Zentralinstitut für Kunstgeschichte[22]

Influences

The Google Art Project was a development of the virtual museum projects of the 1990s and 2000s, following the first appearance of online exhibitions with high-resolution images of artworks in 1995. In the late 1980s, art museum personnel began to consider how they could exploit the internet to achieve their institutions' missions through online platforms. For example, in 1994 Elizabeth Broun, Director of the Smithsonian American Art Museum, spoke to the Smithsonian Commission on the future of art, stating: "We need to put our institutional energy behind the idea of getting the Smithsonian hooked up to the people and schools of America." She then outlined the museum's objective to conserve, protect, present, and interpret exhibits, explaining how electronic media could help achieve these goals.[23] The expansion of internet programs and resources has shaped the development of the platform.[19][24]

Contemporary Google initiatives

Another Google initiative—Google Books—affected the development of the platform from a non-technological perspective. Google faced a six-year-long court case relating to several issues with copyright infringement. Google Books cataloged full digital copies of texts, including those still protected by copyright, though Google claimed it was permissible under the fair use clause. Google ended up paying $125 million to copyright-holders of the protected books, though the settlement agreement was modified and debated several times before it was ultimately rejected by federal courts. In his decision, Judge Denny Chin stated the settlement agreement would "give Google a significant advantage over competitors, rewarding it for engaging in wholesale copying of copyrighted works without permission," and could lead to antitrust issues. Judge Chin said in future open-access initiatives, Google should use an "opt-in" method, rather than providing copyright owners the option to "opt out" of an arrangement.[25]

After this controversy, Google took a different approach to intellectual property rights for the Google Arts & Culture. The platform's intellectual property policy is:

- The high-resolution imagery of artworks featured on the platform site is owned by the museums, and these images may be subject to copyright laws around the world. The Street View imagery is owned by Google. All of the imagery on this site is provided for the sole purpose of enabling you to use and enjoy the benefit of the platform site, in the manner permitted by Google’s Terms of Service. The normal Google Terms of Service apply to your use of the entire site.[20]

The Google team was sensitive to copyright issues of artworks, and partner museum staff were able to ask Google to blur out the images of certain works, which are still protected by copyrights. In a few cases, museums wanted to include artworks by modern and contemporary artists, many of whom still hold the copyright to their work. For example, the Tate Britain approached Chris Ofili to get his permission to capture and reproduce his works on the platform.[17]

However, since the project expanded in April 2012, Google has faced a few intellectual property issues. Some of the works added to the online exhibitions are still protected by copyright, as the artist or his or her heirs holds the right to the image for 70 years. As a result, the Toledo Museum of Art asked Google to remove 21 artworks from the website, including works by Henri Matisse and other modern artists.[26]

Google Cultural Institute

By December 2013, the contents of the project were accessible from Google Cultural Institute, an initiative unveiled by Google following the 2011 launch of Google Arts & Culture (known as Google Art Project at the time of launch).

The Cultural Institute was launched in 2011 with 42 new exhibits online on October 10, 2012.[27][28][29][30][31] The Cultural Institute strove "to make important cultural material available and accessible to everyone and to digitally preserve it to educate and inspire future generations."[32] As of June 2013, it included over 6 million items - photos, videos, and documents.[33]

The initiative has partnered with a number of institutions to make exhibition and archival content available online, including the British Museum,[34][35][36] Yad Vashem,[37][38] the Museo Galileo in Florence,[39] Center for Jewish History in New York City[40], Auschwitz-Birkenau State Museum,[41] and the Museum of Polish History in Warsaw.[42][43] The earliest notable project was a searchable archive and online digital exhibition series, in partnership with the Nelson Mandela Centre of Memory, which allowed people to access Nelson Mandela's personal diaries and previously unreleased drafts of his manuscripts for the sequel to his autobiography Long Walk to Freedom.[44]

In addition to Google Arts & Culture, the Cultural Institute includes the World Wonders Project, which presents three-dimensional recreations of world heritage sites, and archival exhibitions, many in partnership with museums around the world. It also features digitized objects from archives, libraries, and a wider array of museums not strictly devoted to art.[45]

Reception

The Google Arts & Culture stirred up debate among scholars, museum personnel, art critics, and news writers. Since its initial launch, it has received fairly consistent positive feedback and a variety of criticism. With the second generation platform, Google appears to have responded to some earlier criticisms.

Praise

Positive feedback about the platform has centered on an increased audience gaining access to art, the marketing externality for museums, and the potential for the future development of the initiative.

- Increases access to art. So long as one has internet access, anyone, anywhere, at any time can visit the Google Arts & Culture, enabling audiences who otherwise would be unlikely to visit these museums to see their works. "Armchair tourists" are now able to tour some of the world's greatest art exhibits without leaving their seat.[46] Professors and students can go on virtual field trips without the usual associated costs, and have a remote conversation with an expert from a museum or other institution.[4]

- Better visitor experience. Users of the site can avoid constraints of time, money and physical difficulty. They need not plan a restrictive one-time visit to a collection, or arrive to find out work is not on view. They are not bothered by other visitors.

- Triggers new visitors Many art historians and scholars have posited that online exhibitions would drive more people to the gallery, and the Google Arts & Culture has supported this theory. The research established that there is a statistically significant relationship between those who visit the platform and those who are inspired to go on a real tour of a museum.[47] In further support of this concept, within two weeks of the launch of the platform, MoMA saw its website's traffic increase by about 7%.[14] It is, however, unclear how many physical visitors came to MoMA as a result of the platform.

- Complements real visits to a gallery. While there has been some skepticism that the Google Arts & Culture seeks to replace real-time visits to art galleries, many have suggested that the virtual tours actually complement real-time visits. Research shows that people are more likely to enjoy their real-time visit to a museum after participating in a virtual tour.[47] Several museum personnel have supported this concept anecdotally. Julian Raby, director of the Freer Gallery of Art stated: “The gigapixel experience brings us very close to the essence of the artist through detail that simply can’t be seen in the gallery itself. Far from eliminating the necessity of seeing artworks in person, [Arts & Culture] deepens our desire to go in search of the real thing.”[48] This view was shared by Brian Kennedy, director of the Toledo Museum of Art, who believed that academics would still want to view artwork in three dimensions, even if the gigapixel images provided better clarity than viewing the artwork in the gallery. Similarly, Amit Sood—the Google project leader—said that "nothing beats the first-person experience".[19]

- Has future development potential. Some scholars and art critics believe the Google Arts & Culture will change how museums use the web. For instance, Nancy Proctor—Head of Mobile Strategy & Initiatives at the Smithsonian—suggested that museums may eventually utilize the platform to provide museum maps and gallery information instead of printed materials. It might become possible for museum visitors to hold up their smartphone in front of an artwork, and the platform could overlay information. the platform could also provide a seamless transition from a Google Map to an inside gallery map, avoiding the need for printed collateral.[3]

- Democratization of culture. With the rapid increase of information that is available online, we are in a period of democratization of knowledge. An elite group of professionals and experts are no longer the only people with the ability to distribute respected information. Rather, through web-based initiatives like Wikipedia, anyone with web access can contribute to and help shape public knowledge.[49]

The Google Arts & Culture is, according to some, a democratic initiative.[50] It aims to give more people access to art by removing barriers like cost and location. Some art or cultural exhibits have been limited to a small group of viewers (e.g. PhD students, academic researchers) due to deteriorating conditions of work, lack of available wall space in a museum, or other similar factors. Digitized reproductions, however, can be accessible to anyone from any location. This type of online resource can transform research and academia by opening access to previously exclusive artworks, enabling multidisciplinary and multi-institutional learning.[51] It provides people the opportunity to experience art individually, and a platform to become involved in the conversation.[3] For example, the platform now lets users contribute their own content, adding their insight to the public collection of knowledge.

Many scholars have argued that we are experiencing a breakdown of the canon of high art,[23] and the Google Arts & Culture is beginning to reflect this. When it just included the Grand Masters of Western Art, the project faced strong criticism. As a result of this outburst, the website now includes some indigenous and graffiti artworks. This platform also provides a new context through which people encounter art, ultimately reflecting this shift away from the canon of high art.[3]

Criticism

A few initial criticisms of the platform, including the skewed representation of artworks, have lost some validity with the launch of the second generation platform.

- Eurocentrism: During its initial launch, many critics argued that Google Arts & Culture provided a Western-biased representation of art. Most museums included in the first phase of the Project were from Western Europe, Washington, DC, and New York, NY.[52] According to Diana Skaar, head of partnerships for the platform, Google responded: “After the launch of round one, we got an overwhelming response from museums worldwide. So for round two, we really wanted to balance regional museums with those that are more nationally or globally recognized.”[53] Now, the platform's expanded repository includes graffiti works, dot paintings, rock art, and indigenous artworks.[54]

Although the firm may have responded to this issue, there are other neglected criticisms:

- Selection of content: Although the Google Arts & Culture now partners with 134 new museums, some critics believe it still may present a skewed representation of art and art history. Google and the partner museums are able to decide what information to include, and what artworks they will make available (and at what level of quality); some believe this is counter-intuitive to the website's seemingly democratic objective.[55] For example, in the White House virtual collection, one photo of a former First Lady does not include a key piece of information to understand the context of the image. Grace Coolidge often wore brightly colored clothes. In her White House portrait, she was dressed in a red sleeveless flapper dress and stood next to a large white dog. There are two versions of this picture: one showing Coolidge on a white background with softer lines, and one showing her on the White House lawn. The Google Arts & Culture description leaves out the reason for why there are two images. President Coolidge preferred his wife to wear a white dress. The artist, however, wanted the dress to contrast with the white dog. President Coolidge then retorted, "Dye the dog!"[5] While perhaps not crucial to understanding the exhibit, this and other examples show that Google Arts & Culture and partner museums are in a position of power to curate the content and educational information of the virtual exhibition.[55]

- Audience: Some critics have expressed concern over the intended audience of the platform, as this should shape the type of content available through the platform. For example, Director of the Center for the Future of Museums, Elizabeth Merritt, described the project as an "interesting experiment" but was skeptical as to its intended audience.[19]

- Possible security risks: Some critics have raised the question of how Arts & Culture visitors might maliciously use the Street View images. For example, by providing highly detailed images of galleries, people could use this platform to map out museum security systems, and then be able to circumvent these protective measures during a break-in.[56]

Similar initiatives

Many museums and arts organizations have created their own online data and virtual exhibitions. Some offer virtual 3-D tours similar to the Google Arts & Culture's gallery view, whereas others simply reproduce images from their collection on the institution's web page. Some museums have collections that exist solely in cyberspace and are known as virtual museums.

- Bucharest Natural History Museum[58] and the Museum of the Romanian Peasant[59] offer virtual tours of two of Romania's larger historical/anthropological museums.

- Europeana is a virtual repository of artworks, literature, cultural objects, relics, and musical recordings/writings from over 2000 European institutions.[60]

- Images for the Future[61] is a project dedicated to digitizing audiovisual cultural objects of the Netherlands, and making these exhibits available through its online archive.[61]

- Public Art in Public Places is a not-for-profit arts public art initiative that publishes an online digital archive of public artworks, statues, memorials and monuments in Southern California and Hawaii, United States, as well as public art news and editorial features.

- Public Catalogue Foundation has digitized all the circa 210,000 oil paintings in public ownership in the United Kingdom, and made the paintings viewable by the public through a series of affordable catalogues and, in partnership with the BBC, the "Your Paintings" website.[62] Works by some 40,000 painters are included.

- Khan Academy's smARThistory is a multimedia resource with videos, audio guides, mobile applications and commentary from art historians.

- The Prado launched a virtual collection, in collaboration with Google Earth, in January 2009. The website contained photos of 14 Prado paintings, each with up to 14 gigapixels.

- The Virtual Museum of Canada is a virtual collection containing exhibits from thousand of Canadian local, provincial and national museums.

- Tripbru is a digital tourism platform for Museums, Cities and Cultural Centers with particular focus on expert collaborators providing premium content.[63]

- Wikipedia GLAM ("galleries, libraries, archives, and museums", also including botanic and zoological gardens) helps cultural institutions share their resources with the world through collaborative projects with experienced Wikipedia editors.

Footnotes

- Valvo, Michael. "Google Goes Global with Expanded Art Project" (Press release). Google Art Project. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Pack, Thomas (May 2011). "The Google Art Project is a Sight to Behold". Information Today. Vol. 28 no. 5.

- Proctor, Nancy (April 2011). "The Google Art Project: A new Generation of Museums on the Web?". Curator: The Museum Journal. 52 (2).

- Stanislawski, Piotr (3 April 2012). "Polska Sztuka w Google Art Project". Gazeta. Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Keyes, Alexa (3 April 2012). "Google Art Project and White House Launch 360 Tour of 'People's House'". ABC News. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Heller, Aron (3 April 2012). "Israel Museum showcased in Google Art Project". Gainesville Times/Associated Press. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Education". Google Art Project. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- "Art Selfie". Google’s art app is now top of iOS and Android download charts.

- "Art Selfie". Out How to Make People Care About Art.

- "Art Selfie". Votre selfie est une œuvre d’art mais vous ne le savez pas encore.

- Knowles, Jemillah. "Google's Art Project grows larger with 151 museums online across 140 countries". TNW Google Blog. The Next Web. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Sood, Amit. "Explore museums and great works of art in the Google Art Project". Google Official Blog. Retrieved 22 March 2012.

- "About Google". Retrieved 25 March 2012.

- Berwick, Carly (April 2011). "Up Close and Personal with Google Art Project". Art in America. Vol. 99 no. 4.

- Waters, Florence (1 February 2011). "The best online culture archives". The Telegraph. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Ngak, Chenda. "Google Art Project features White House, the Met, National Gallery". CBS News. Retrieved April 15, 2012.

- Davis, James. "Google Art Project: Behind the Scenes". Tate Blogs. Tate Britain. Archived from the original on 24 December 2012. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Mediati, Nick (April 2011). "An extension of Google Street View enables interactive, Web-based virtual museum tours". PC World. Vol. 29 no. 4.

- Kennicott, Philip (1 February 2011). "National Treasures: Google Art Project unlocks riches of world's galleries". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- "FAQs". Google Art Project. Retrieved 10 April 2012.

- "Google and museums around the world unveil Art Project" (Press release). Google Art Project. Retrieved 1 February 2011.

- https://artsandculture.google.com/partner?tab=az

- Broun, Elizabeth (Summer 1994). "The Future of Art at the Smithsonian". American Art. 8 (3/4): 2–7. doi:10.1086/424219. JSTOR 3109168.(registration required)

- Proctor, N (2011). "The Google Art Project: A New Generation of Museums on the Web?". Curator: The Museum Journal. 54 (2): 215–221. doi:10.1111/j.2151-6952.2011.00083.x.

- Efrati, Amir. "Judge Rejects Google Books Settlement". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved 9 April 2012.

- Cohen, Patricia (24 April 2012). "Art is Long; Copyrights Can Be Even Longer". The New York Times. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Yoshitake, Mark. "Bringing history to life". Google Official Blog. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- Pfanner, Eric. "Quietly, Google Puts History Online". The New York Times. November 21, 2011.

- Newton, Casey. "Google Cultural Institute brings dozens of new exhibits online". CNET. October 10, 2012.

- Stephens, Simon. "Google Unveils Museum Exhibitions Project". Museums Journal. 10 October 2012.

- "Google Brings History to Life with Online Exhibitions". Mashable.com. October 10, 2012.

- Google Cultural Institute. "Frequently Asked Questions".

- "From Sutton Hoo to the soccer pitch: culture with a click". Google Official Blog. June 25, 2013.

- "British Museum". Google Cultural Institute.

- "The British Museum". British Museum.

- "The Sutton Hoo Ship Burial". British Museum.

- "Helping Google Bring History to Life". Achievements and Challenges: Annual Report 2012. p. 30.

- "Yad Vashem: Remembering the Holocaust".

- "The Museo Galileo on the Google Cultural Institute Archived 2013-07-17 at Archive.today".

- "Center for Jewish History". Google Cultural Institute.

- "Poland Joins Google Cultural Institute Archived 2012-10-26 at the Wayback Machine". Culture.pl. October 11, 2012.

- "Wystawa Muzeum Historii Polski w Google Cultural Institute". (in Polish)

- "Polska historia w Google Cultural Institute". Polskie Radio. October 10, 2012 (in Polish).

- Yoshitake, Mark. "Explore Mandela's archives online". Google Official Blog. Retrieved 19 October 2014.

- "Our Projects". Google Cultural Institute.

- Ionescu, Daniel. "Google's Art Project Extended Worldwide". PC World Blogs. PC World. Archived from the original on 2013-11-04. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Bararia, Khushboo. "Promotion of Virtual Tourism through Google Art Projects". Masters Thesis. Christ University. Archived from the original on 2 March 2013. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Sood, Amit. "Amit Sood: Technologist". Speakers. TED. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- Sanger, Larry. "Who Says We Know: On the New Politics of Knowledge". Edge: The Third Culture. Archived from the original on 22 December 2012. Retrieved 26 April 2012.

- Inanoglu, Zeynep. "Google Art Project: Democratizing Art" (PDF). Retrieved 8 April 2012.

- Guerlac, Suzanne (Fall 2011). "Humanities 2.0: E-Learning in the Digital World". Representations. The Humanities and the Crisis of the Public University. 116 (1): 102–127. doi:10.1525/rep.2011.116.1.102.

- Anonymous (3 February 2011). "Getting in close and impersonal". The Economist. ProQuest 849706905.

- Finkel, Jori (2 April 2012). "LACMA, Getty among 134 museums joining Google's art site". LA Times. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Hayward, Andrea (4 April 2012). "ARTS: Global artworks now a click away". Australian Associated Press Pty Limited. ProQuest 963815632.

- Sooke, Alistair (1 February 2011). "The Problem With Google's Art Project". The Telegraph. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Nonnenmacher, Peter (8 February 2011). "Virtuelle Tiefenschärfe". Wiener Zeitung. Retrieved 6 April 2012.

- Andy MacLean. "Wiki Loves Art Nouveau". europeana.eu.

- Ovidiu Sopa @ office@sibiul.ro. "Muzeul National de Istorie Naturala Grigore Antipa #48". Antipa.ro. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- "Tur Virtual – Muzeul Taranului Roman". Tour.muzeultaranuluiroman.ro. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- McKenn, Brian (April 2011). "Europeana Stretches as Google Expands". Information Today. Vol. 28 no. 4. pp. 14–15. ProQuest 861737013.

- "Images for the Future". Imagesforthefuture.com. Retrieved 2012-04-19.

- https://artuk.org/

- "Smart Digital Tourism Platform".

Sources

- "Google Art: See Paintings like never before", BananaBandy, 6 June 2016. Retrieved on 6 June 2016.

- Google (1 February 2011). "Google and Museums Around the World Unveil Art Project". London: Google, Inc. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Kennicott, Philip (1 February 2011). "National Treasures: Google Art Project Unlocks Riches of World's Galleries". The Washington Post. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- "Google Art Project: The 7 Billion Pixel Masterpieces". The Daily Telegraph. London. 1 February 2011. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

- Tremlett, Giles (14 January 2009). "Online gallery zooms in on Prado's masterpieces (even the smutty bits)". The Guardian. London.

- Waters, Florence (1 February 2011). "The Best Online Culture Archives". The Daily Telegraph. London. Retrieved 2 February 2011.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Google Art Project. |