Gomphothere

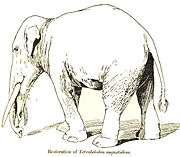

Gomphotheres are any members of the diverse, extinct taxonomic family Gomphotheriidae. Gomphotheres were elephant-like proboscideans, but not belonging to the family Elephantidae. They were widespread in North America during the Miocene and Pliocene epochs, 12–1.6 million years ago (Mya). Some lived in parts of Eurasia, Beringia, and South America following the Great American Interchange. While most famous forms such as Gomphotherium had long lower jaws with tusks, which is the ancestral condition for the group, after these forms became extinct, the surviving gomphotheres had short jaws with either vestigal or no lower tusks (brevirostrine), looking very similar to modern elephants, an example of parallel evolution. Beginning after 2 Mya, they were gradually replaced by mammoths and mastodons in most of North America, with the last two genera, Cuvieronius persisting in southern North America and Notiomastodon having a wide range over most of South America, until the end of the Pleistocene.

| Gomphothere | |

|---|---|

| |

| Specimen of Gomphotherium productum at the AMNH | |

| Notiomastodon platensis Centro Cultural del Bicentenario de Santiago del Estero in Argentina | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Proboscidea |

| Superfamily: | †Gomphotherioidea |

| Family: | †Gomphotheriidae (Hay, 1922) A. Cabrera 1929 |

| Genera[1] | |

| |

The name "gomphothere" comes from Ancient Greek γόμφος (gómphos), "peg, pin; wedge; joint" plus θηρίον (theríon), "beast".

Description

Gomphotheres differed from elephants in their tooth structure, particularly the chewing surfaces on the molar teeth. The earlier species had four tusks, and their retracted facial and nasal bones prompted paleontologists to believe that gomphotheres had elephant-like trunks.[2]

Taxonomy

Both the genus Gomphotherium and family Gomphotheriidae were erected by the German zoologist Karl Hermann Konrad Burmeister (1807-1892) in 1837.

The term gomphothere as historically used (sensu lato) is paraphyletic, containing all proboscideans more derived than mammutids, but less derived than elephantids. The term gomphothere sensu stricto refers specifically to trilophodont gomphotheres. The genera Anancus, Morrillia, Paratetralophodon, and Tetralophodon, but also the families Choerolophodontidae and Amebelodontidae, were formerly classified as gomphotheres sensu lato. Tetralophodont gompotheres are more closely related to the Elephantidae and amebelodonts and choerolophodonts more primitive than trilophodont gomphotheres.[3][4][5] In 2019, a study using collagen sequencing found Notiomastodon to form a clade with the American mastodon, rather than closer to the Elephantidae, as had previously been supposed.[6] The idea that the Mammutidae and Gomphotheriidae are closely related was supported by a morphological study in 2020, which noted the similarity of the molars of the newly resurrected mammutid genus Miomastodon and those of Gomphotherium subtapiroideum/tassyi.[7] Phylogeny of trilophodont gomphotheres according to Mothé et al., 2016:[5]

†Gomphotheriidae (Gomphotheres) |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Diet

Isotopic analyses of South American gomphotheres suggest a wide diet for Notiomastodon platensis, except for the fossils unearthed at the localities in Santiago del Estero and La Carolina in Ecuador. Isotope analyses suggested an exclusive C4 diet, whereas every other South American locality indicates an exclusive C3 or mixed C3 and C4 diets. The results also support the latitudinal gradient of C3 and C4 grasses. The stereomicrowear analyses for N. platensis exhibited average scratch and pit values, which place it within the extant mixed-feeder morphospace and the higher frequency of fine scratches indicated the ingestion of C3 grasses.

Alternatively, the presence of coarse and hypercoarse scratches along with gouges and large pits suggests the ingestion of foliage and lignified portions. The plant microfossil analysis recovered fragments of conifer tracheid and vessel elements with a ray of parenchyma cells, which corroborates the consumption of woody plants, pollen grains, spores, and fibers.

The Aguas de Araxa gomphotheres were generalist feeders and consumed wood elements, leaves, and C3 grasses.[8] Cuvieronius specimens from Chile were exclusively C3 plant eaters, whereas specimens from Bolivia and Ecuador are classified as having a mixed C3 and C4 diet. Notiomastodon showed a wider range of dietary adaptations. Specimens from Quequen Salado in Buenos Aires Province were entirely C3 feeders, whereas the diet of specimens from La Carolina Peninsula in Ecuador was exclusively C4.[9]

Possible causes for extinction

The results confirm that ancient diets cannot always be interpreted solely from dental morphology or extrapolated from present relatives. The data from Middle and Late Pleistocene periods indicate that over time, a shift occurred in dietary patterns away from predominantly mixed feeders to more specialized feeders. This dietary evolution may have been one of the factors that contributed to the disappearance of South American gomphotheres at the end of the Pleistocene.[10] Climatic change and human predation have also been discussed as possible causes of the extinction.[11]

Associations with early human sites

Gomphothere remains are common at South American Paleo-Indian sites.[12] Examples include the early human settlement at Monte Verde, Chile, dating to around 14,000 years ago, and the Altiplano Cundiboyacense (Tibitó, 11,740 years ago), and the Valle del Magdalena of Colombia.[13] In 2011, remains dating between 10,600 and 11,600 years ago were also found in the El Fin del Mundo (End of the World) site in Sonora, Mexico's Clovis location – the first time such an association was found in a northern part of the continent where gomphotheres had been thought to have gone extinct 30,000 years ago.[14] As announced in July 2014, the "position and proximity of Clovis weapon fragments relative to the gomphothere bones at the site suggest that humans did in fact kill the two animals there. Of the seven Clovis points found at the site, four were in place among the bones, including one with bone and teeth fragments above and below. The other three points had clearly eroded away from the bone bed and were found scattered nearby."[15]

Gallery

Gomphotherium angustidens

Gomphotherium angustidens.jpg) Gomphothere models in Osorno

Gomphothere models in Osorno

References

- Shoshani, Jeheskel; Pascal Tassy (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126-128: 5–20. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126....5S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

- Palmer, D., ed. (1999). The Marshall Illustrated Encyclopedia of Dinosaurs and Prehistoric Animals. London, UK: Marshall Editions. pp. 239–242. ISBN 1-84028-152-9.

- Shoshani, J.; Tassy, P. (2005). "Advances in proboscidean taxonomy & classification, anatomy & physiology, and ecology & behavior". Quaternary International. 126-128: 5–20. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126....5S. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.011.

- Wang, Shi-Qi; Deng, Tao; Ye, Jie; He, Wen; Chen, Shan-Qin (2016). "Morphological and ecological diversity of Amebelodontidae (Proboscidea, Mammalia) revealed by a Miocene fossil accumulation of an upper-tuskless proboscidean". Systematic Palaeontology (Online ed.). 15 (8): 601–615. doi:10.1080/14772019.2016.1208687.

- Mothé, Dimila; Ferretti, Marco P.; Avilla, Leonardo S. (12 January 2016). "The dance of tusks: Rediscovery of lower incisors in the pan-American proboscidean Cuvieronius hyodon revises incisor evolution in elephantimorpha". PLOS ONE. 11 (1): e0147009. Bibcode:2016PLoSO..1147009M. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0147009. PMC 4710528. PMID 26756209.

- Buckley, Michael; Recabarren, Omar P.; Lawless, Craig; García, Nuria; Pino, Mario (November 2019). "A molecular phylogeny of the extinct South American gomphothere through collagen sequence analysis". Quaternary Science Reviews. 224: 105882. Bibcode:2019QSRv..22405882B. doi:10.1016/j.quascirev.2019.105882.

- Shi-Qi Wang; Xiao-Xiao Zhang; Chun-Xiao Li (2020). "Reappraisal of Serridentinus gobiensis Osborn & Granger and Miomastodon tongxinensis Chen: the validity of Miomastodon". Vertebrata PalAsiatica. 58 (2): 134–158. doi:10.19615/j.cnki.1000-3118.200310.

- Asevedo, Lidiane; Winck, Gisele R.; Mothe, Dimila; Avilla, Leonardo S. (2012). "Ancient diet of the pleistocene gomphothere Notiomastodon platensis (Mammalia, Proboscidea, Gomphotheriidae) from Lowland Mid-latitudes of South America: Stereomicrowear and Tooth Calculus Analyses Combined". Quaternary International. 255: 45–52. Bibcode:2012QuInt.255...42A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2011.08.037.

- Alberdi, Maria Teresa; Prado, José Luis; Perea, Daniel; Ubilla, Martin (2007). "Stegomastodon waringi (Mammalia, Proboscidea) from the Late Pleistocene of northeastern Uruguay". Neues Jahrbuch für Geologie und Paläontologie - Abhandlungen. 243 (2): 179–189. doi:10.1127/0077-7749/2007/0243-0179.

- Sanchez, Begoña; Prado, José Luis; Alberdi, Maria Teresa (2004). "Feeding ecology, dispersal, and extinction of South American pleistocene gomphotheres (Gomphotheriidae, Proboscidea)". Paleobiology. 30 (1): 146–161. doi:10.1666/0094-8373(2004)030<0146:fedaeo>2.0.co;2.

- Bertoni-Machado, Cristina (2012). "Extinction of a gomphothere population from Southeastern Brazil: Taphonomic, paleoecological and chronological remarks". Quaternary International. 305: 85–90. Bibcode:2013QuInt.305...85A. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2012.09.015. Retrieved 16 June 2014.

- Prado, J.L.; Alberdi, M.T.; Azanza, B.; Sánchez, B.; Frassinetti, D. (2005). "The Pleistocene Gomphotheriidae (Proboscidea) from South America". Quaternary International. 126-128: 21–30. Bibcode:2005QuInt.126...21P. doi:10.1016/j.quaint.2004.04.012.

- Rodríguez-Flórez, Carlos David; Rodríguez-Flórez, Ernesto León; Rodríguez, Carlos Armando (2009). Revision of Pleistocenic Gomphotheriidae fauna in Colombia and case report in the department of Valle del Cauca (PDF). Scientific Bulletin. 13. Museum Center - Natural History Museum. pp. 78–85. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 July 2011. Retrieved 9 November 2010.

- "Finding would reveal contact between humans and gomphotheres in North America". Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia. 24 January 2011. Retrieved 26 May 2014.

- "Bones of elephant ancestor unearthed: Meet the gomphothere". Science Daily. University of Arizona. 14 July 2014. Retrieved 31 August 2018.

External links

- "Buried Treasure in the Sierra Nevada Foothills". Sierra College. (article about a fossil exhibit at the Sierra College Natural History Museum)

- "Gomphothere description including images". Sierra College.

- ""King Tusk" Gomphothere Excavation". Sierra College. (photos from the excavation of a Gomphothere skeleton on the Sierra College website)

- "The Gomphotheriidae". University of California Museum of Paleontology.