Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson

Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson (or de Roucy), also known as Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson (29 January 1767 – 9 December 1824),[1] was a French painter and pupil of Jacques-Louis David, who participated in the early Romantic movement by including elements of eroticism in his paintings. Girodet is remembered for his precise and clear style and for his paintings of members of the Napoleonic family.

Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson | |

|---|---|

Self-portrait, 1790, Hermitage Museum | |

| Born | Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson 29 January 1767 |

| Died | 9 December 1824 (aged 57) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Père Lachaise Cemetery |

| Nationality | French |

| Known for | Painting |

Notable work | Ossian receiving the ghosts of the fallen French Heroes, 1801; The Funeral of Atala, 1808; Portrait de Chateaubriand méditant sur les ruines de Rome, after 1808 |

| Movement | Classicism, Romanticism |

Early career

Girodet was born at Montargis. Both of his parents died when he was a young adult. The care of his inheritance and education fell to his guardian, a prominent physician named Benoît-François Trioson, "médecin-de-mesdames", who later adopted him. The two men remained close throughout their lives and Girodet took the surname Trioson in 1812.[1] In school he first studied architecture and pursued a military career.[2] He changed to the study of painting under a teacher named Luquin and then entered the school of Jacques-Louis David. At the age of 22 he successfully competed for the Prix de Rome with a painting of the Story of Joseph and his Brethren.[2][3] From 1789 to 1793 he lived in Italy and while in Rome he painted his Hippocrate refusant les presents d'Artaxerxes and Endymion-dormant (now in the Louvre), a work which gained him great acclaim at the Salon of 1793 and secured his reputation as a leading painter in the French school.

Once he returned to France, Girodet painted many portraits, including some of members of the Bonaparte family. In 1806, in competition with the Sabines of David, he exhibited his Scène de déluge (Louvre), which was awarded the decennial prize.[1] In 1808 he produced the Reddition de Vienne and Atala au tombeau, a work which won immense popularity, by its fortunate choice of subject – François-René de Chateaubriand's novel Atala, first published in 1801 – and its remarkable departure from the theatricality of Girodet's usual manner. He would return to his theatrical style in La Révolte du Caire (1810).[4]

Later life

Girodet was a member of the Academy of Painting and of the Institut de France, a knight of the Order of Saint Michael, and officer of the Legion of Honour.[1] Among his pupils were Hyacinthe Aubry-Lecomte, Augustin Van den Berghe the Younger, François Edouard Bertin, Angélique Bouillet, Alexandre-Marie Colin, Marie Philippe Coupin de la Couperie, Henri Decaisne, Paul-Emile Destouches, Achille Devéria, Eugène Devéria, Savinien Edme Dubourjal, Joseph Ferdinand Lancrenon, Antonin Marie Moine, Jean Jacques François Monanteuil, Henry Bonaventure Monnier, Rosalie Renaudin, Johann Heinrich Richter, François Edme Ricois, Joseph Nicolas Robert-Fleury, and Philippe Jacques Van Brée.[5]

In his forties his powers began to fail, and his habit of working at night and other excesses weakened his constitution. In the Salon of 1812 he exhibited only a Tête de Vierge; in 1819 Pygmalion et Galatée showed a further decline of strength. In 1824, the year in which he produced his portraits of Cathelineau and Bonchamps, Girodet died on December 9 in Paris.[4] At a sale of his effects after his death, some of his drawings realized enormous prices.[1]

Posthumously published work

Girodet produced a vast quantity of illustrations, amongst which may be cited those for the Didot editions of the works of Virgil (1798) and Racine (1801–1805). Fifty-four of his designs for the works of the ancient Greek poet Anacreon were engraved by M. Châtillon. Girodet used much of his time on literary composition. His poem Le Peintre (rather a string of commonplaces), together with poor imitations of classical poets, and essays on Le Génie and La Grâce, were published posthumously in 1829, with a biographical notice by his friend Coupin de la Couperie. Delecluze, in his Louis David et son temps, has also a brief life of Girodet.[4][1]

Girodet: Romantic Rebel at the Art Institute of Chicago (2006) was the first retrospective in the United States devoted to the works of Anne-Louis Girodet de Roussy-Trioson. The exhibition assembled more than 100 seminal works (about 60 paintings and 40 drawings) that demonstrated the artist's range as a painter as well as a draftsman.[6]

Analysis of the works

Girodet was trained in the neoclassical style of his teacher, Jacques-Louis David, seen in his treatment of the male nude body and his reference to models from the Renaissance and Classical antiquity. However, he also deviated from this style in several ways. The peculiarities which mark Girodet's position as the herald of the romantic movement are already evident in his Sleep of Endymion (1791, also called Effet de lune or "effect of the Moon").[4] Although the subject matter and pose are inspired by classical precedents, Girodet's diffuse lighting is more theatrical and atmospheric. The androgynous depiction of the sleeping shepherd Endymion is also noteworthy.[7] These early romantic effects were even more notable in his Ossian, exhibited in 1802. Girodet portrayed recently killed Napoleonic soldiers being welcomed into Valhalla by the fictional bard Ossian. The painting is striking for its inclusion of phosphorescent meteors, vaporous luminosity, and spectral protagonists.[8]

The same coupling of classic and romantic elements marks Girodet's Danae (1799) and his Quatre Saisons, executed for the king of Spain (repeated for Compiègne), and shows itself to a ludicrous extent in his Fingal (Leuchtenberg collection, St. Petersburg), executed for Napoleon in 1802. Girodet can be seen here combining aspects of his classical training and traditional education with new literary trends, popular scientific spectacles, and a consummate interest in the strange and the bizarre. In this way his work announces the rise of a romantic aesthetic which prizes individuality, expression, and imagination over an adherence to classical academic precedents.

Gallery

Brutus condemns his sons to death (Brutus condamne ses fils à mort), 1785

Brutus condemns his sons to death (Brutus condamne ses fils à mort), 1785 The Oath of the Horatii (Le Serment des Horaces, copy after David's original), 1786, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio

The Oath of the Horatii (Le Serment des Horaces, copy after David's original), 1786, Toledo Museum of Art, Ohio The Death of Tatius (La mort de Tatius), 1788, Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Angers

The Death of Tatius (La mort de Tatius), 1788, Musée des Beaux-Arts d'Angers- Joseph recognized by his brothers (Joseph reconnu par ses frères), 1789, École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts, Paris

Portrait of a Youth (Portrait d'une jeunesse), c. 1795, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts

Portrait of a Youth (Portrait d'une jeunesse), c. 1795, Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts Portrait of Giuseppe Fravega (ministre of the Ligurian Republic in Paris), 1796, Musée des beaux-arts de Marseille

Portrait of Giuseppe Fravega (ministre of the Ligurian Republic in Paris), 1796, Musée des beaux-arts de Marseille Benoît-Agnès Trioson regardant des figures dans un livre, 1797, Musée Girodet, Montargis

Benoît-Agnès Trioson regardant des figures dans un livre, 1797, Musée Girodet, Montargis Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, Deputy for Saint-Domingue, 1797, Palace of Versailles

Portrait of Jean-Baptiste Belley, Deputy for Saint-Domingue, 1797, Palace of Versailles

Benoît-Agnes Trioson, 1800, Louvre, Paris

Benoît-Agnes Trioson, 1800, Louvre, Paris

.jpg) Napoleon Bonaparte, Premier Consul, Palais de l'Elysée

Napoleon Bonaparte, Premier Consul, Palais de l'Elysée Portrait of Dominique-Jean Larrey (military surgeon in Napoleon's army), 1804, Louvre

Portrait of Dominique-Jean Larrey (military surgeon in Napoleon's army), 1804, Louvre- Portrait of the Katchef Dahouth, Christian Mameluke, 1804, Art Institute of Chicago

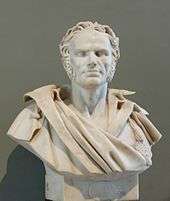

Charles Marie Bonaparte

Charles Marie Bonaparte

(father of Napoléon Bonaparte), 1806

Madame Erneste Bioche de Misery, 1807, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa

Madame Erneste Bioche de Misery, 1807, National Gallery of Canada, Ottawa Portrait de Chateaubriand méditant sur les ruines de Rome, 1808, Musée d'Histoire de la Ville et du Pays Malouin, Saint-Malo

Portrait de Chateaubriand méditant sur les ruines de Rome, 1808, Musée d'Histoire de la Ville et du Pays Malouin, Saint-Malo Portrait of Hortense de Beauharnais, Queen of Holland, wife of King Louis Napoleon, c. 1809, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam

Portrait of Hortense de Beauharnais, Queen of Holland, wife of King Louis Napoleon, c. 1809, Rijksmuseum, Amsterdam.jpg) Sketch for The Revolt at Cairo, c. 1809, Cleveland Museum of Art

Sketch for The Revolt at Cairo, c. 1809, Cleveland Museum of Art.jpg) The Revolt of Cairo, oil and Indian ink on paper, c. 1810, Art Institute of Chicago

The Revolt of Cairo, oil and Indian ink on paper, c. 1810, Art Institute of Chicago

.jpg) Portrait of Charles-Louis Balzac, 1811, Dallas Museum of Art

Portrait of Charles-Louis Balzac, 1811, Dallas Museum of Art.jpg)

Portrait of Prosper de Barante, 1814, Musée d'art Roger-Quilliot, Clermont-Ferrand

Portrait of Prosper de Barante, 1814, Musée d'art Roger-Quilliot, Clermont-Ferrand Allegory of Victory, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne

Allegory of Victory, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne Aurora, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne

Aurora, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne Minerva between Apollo and Mercury, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne

Minerva between Apollo and Mercury, c. 1815, Château de Compiègne Jacques Cathelineau, généralissime vendéen, 1816, Musée d'art et d'histoire de Cholet

Jacques Cathelineau, généralissime vendéen, 1816, Musée d'art et d'histoire de Cholet Charles-Melchior Arthus, Marquis de Bonchamps, 1816, Musée d'art et d'histoire de Cholet

Charles-Melchior Arthus, Marquis de Bonchamps, 1816, Musée d'art et d'histoire de Cholet- Pygmalion et Galatée, 1819, Château de Dampierre

Portrait de Madame Reizet assise, 1820

Portrait de Madame Reizet assise, 1820_MET_DP135222.jpg) Madame Jacques-Louis-Étienne Reizet, 1823, Metropolitan Museum of Art

Madame Jacques-Louis-Étienne Reizet, 1823, Metropolitan Museum of Art Portrait of Jacques-Joseph de Cathelineau (1787–1832), son of the généralissime

Portrait of Jacques-Joseph de Cathelineau (1787–1832), son of the généralissime_-_Nationalmuseum_-_183684.tif.jpg) Capaneus, Leader of The Seven against Thebes (Tête du Blasphémateur), study for Les sept chefs devant Thèbes, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm

Capaneus, Leader of The Seven against Thebes (Tête du Blasphémateur), study for Les sept chefs devant Thèbes, Nationalmuseum, Stockholm Undated portrait of François-René de Chateaubriand

Undated portrait of François-René de Chateaubriand Portrait du Docteur Trioson donnant une leçon de géographie à son fils, undated, Musée Girodet, Montargis

Portrait du Docteur Trioson donnant une leçon de géographie à son fils, undated, Musée Girodet, Montargis Portrait of Joachim Murat (?), Hermitage Museum

Portrait of Joachim Murat (?), Hermitage Museum

See also

References

- Long, George. (1851) The Supplement to the Penny Cyclopædia of the Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge, C. Knight.

- Polet, Jean-Claude. (1992) Patrimoine littéraire européen, De Boeck Université. 730 pages. ISBN 2-8041-1526-7.

- Heck, Johann Georg. (1860) Iconographic Encyclopaedia of Science, D. Appleton and company.

-

- Anne Louis Girodet-Trioson in the RKD

- "Girodet: Romantic Rebel". Art Institute of Chicago. Archived from the original on 23 July 2006. Retrieved 2006-07-19.

- Smalls, James (1996). "Making Trouble for Art History: The Queer Case of Girodet". Art Journal. 55 (4): 20–27. doi:10.2307/777650. JSTOR 777650.

- O'Rourke, Stephanie (2018). "Girodet's Galvanized Bodies". Art History. 41 (5): 868–893. doi:10.1111/1467-8365.12401.

Further reading

- French painting 1774-1830: the Age of Revolution. New York; Detroit: The Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Detroit Institute of Arts. 1975. (see index)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Anne-Louis Girodet-Trioson. |

- Miscellaneous works (Art Renewal Center)

- Three portraits by Girodet (Insecula encyclopedia)

- Works of Girodet at http://www.the-athenaeum.org