Giant trevally

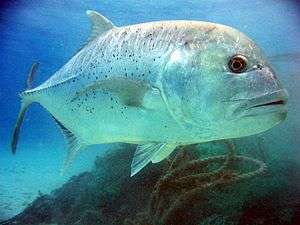

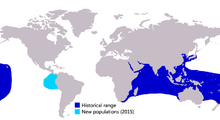

The giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis), also known as the lowly trevally, barrier trevally, giant kingfish or ulua, is a species of large marine fish classified in the jack family, Carangidae. The giant trevally is distributed throughout the tropical waters of the Indo-Pacific region, with a range stretching from South Africa in the west to Hawaii in the east, including Japan in the north and Australia in the south. Two were documented in the eastern tropical Pacific in the 2010s (one captured off Panama and another sighted at the Galápagos), but it remains to be seen if the species will become established there.[2]

| Giant trevally | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Actinopterygii |

| Order: | Carangiformes |

| Family: | Carangidae |

| Genus: | Caranx |

| Species: | C. ignobilis |

| Binomial name | |

| Caranx ignobilis (Forsskål, 1775) | |

| |

| Approximate range of the giant trevally: dark blue (typical range), light blue (two known specimens) | |

| Synonyms | |

The giant trevally is distinguished by its steep head profile, strong tail scutes, and a variety of other more detailed anatomical features. It is normally a silvery colour with occasional dark spots, but males may be black once they mature. It is the largest fish in the genus Caranx, growing to a maximum known size of 170 cm (67 in) and a weight of 80 kg (176 lbs). The giant trevally inhabits a wide range of marine environments, from estuaries, shallow bays and lagoons as a juvenile to deeper reefs, offshore atolls and large embayments as an adult. Juveniles of the species are known to live in waters of very low salinity such as coastal lakes and upper reaches of rivers, and tend to prefer turbid waters.

The giant trevally is an apex predator in most of its habitats, and is known to hunt individually and in schools. The species predominantly takes various fish as prey, although crustaceans, cephalopods and molluscs make up a considerable part of their diets in some regions.

The giant trevally employs novel hunting strategies, including shadowing monk seals to pick off escaping prey, as well as using sharks to ambush prey. Footage released in 2017 on Blue Planet II revealed a group of approximately 50 giant trevally hunting terns, specifically fledglings still learning to fly and which crash land in the water, as well as both fledglings and adults unfortunate enough to fly low enough for the fish to pounce on them, in Farquhar Atoll in the Seychelles.

The giant trevally reproduces in the warmer months, with peaks differing by region. Spawning occurs at specific stages of the lunar cycle, when large schools congregate to spawn over reefs and bays, with reproductive behaviour observed in the wild. The fish grows relatively fast, reaching sexual maturity at a length of around 60 cm at three years of age.

The giant trevally is both an important species to commercial fisheries and a recognised gamefish, with the species taken by nets and lines by professionals and by bait and lures by anglers. Catch statistics in the Asian region show hauls of 4,000–10,000 tonnes, while around 10,000 lbs of the species is taken in Hawaii each year. The species is considered poor to excellent table fare by different authors, although ciguatera poisoning is common from eating the fish. Dwindling numbers around the main Hawaiian Islands have also led to several proposals to reduce the catch of fish in this region.

Taxonomy and phylogeny

The giant trevally is classified within the genus Caranx, one of a number of groups known as the jacks or trevallies. Caranx itself is part of the larger jack and horse mackerel family Carangidae, which in turn is part of the order Carangiformes.[3]

The giant trevally was first scientifically described by the Swedish naturalist Peter Forsskål in 1775 based on specimens taken from the Red Sea off both Yemen and Saudi Arabia, with one of these designated to be the holotype.[4] He named the species Scomber ignobilis, with the specific epithet Latin for "unknown", "obscure" or "ignoble".[5] It was assigned to the mackerel genus Scomber, where many carangids were placed before they were classified as a separate family. This later revision in classification saw the species moved to the genus Caranx, where it has remained.[6] Even after its initial description, the giant trevally (and the bigeye trevally) were often confused with the Atlantic crevalle jack, Caranx hippos, due to their superficial similarity, which led to some authors claiming the crevalle jack had a circumtropical distribution.[7] After Forsskål's initial description and naming, the species was independently renamed three times as Caranx lessonii, Caranx ekala and Carangus hippoides, all of which are now considered invalid junior synonyms.[8] The latter of these names once again highlighted the similarity with the crevalle jack, with the epithet hippoides essentially meaning "like Carangus hippos",[9] which was the crevalle jack's Latin name at that time. Despite the resemblance with the crevalle jack, the two species have never been phylogenetically compared, either morphologically or genetically, to determine their relationship.

C. ignobilis is most commonly referred to as the giant trevally (or giant kingfish) due to its large maximum size, with this often abbreviated to simply GT by many anglers.[10] Other names occasionally used include lowly trevally, barrier trevally, yellowfin jack (not to be confused with Hemicaranx leucurus), Forsskål's Indo-Pacific jack fish and Goyan fish.[6] In Hawaii, the species is almost exclusively referred to as ulua, often in conjunction with the prefixes black, white, or giant.[11] Due to its wide distribution, many other names for the species in different languages are also used.[6] In the Philippines, the species is referred to as talakitok. Some success has been achieved in raising giant trevally commercially in small fish farms there, typically to an age of seven months.

Description

The giant trevally is the largest member of the genus Caranx, and the fifth-largest member of the family Carangidae (exceeded by the yellowtail amberjack, greater amberjack, leerfish and rainbow runner), with a recorded maximum length of 170 cm and a weight of 80 kg.[6] Specimens this size are very rare, with the species only occasionally seen at lengths greater than 80 cm.[12] It appears the Hawaiian Islands contain the largest fish, where individuals over 100 lbs are common. Elsewhere in the world, only three individuals over 100 lbs have been reported to the IGFA.[13]

The giant trevally is similar in shape to a number of other large jacks and trevallies, having an ovate, moderately compressed body with the dorsal profile more convex than the ventral profile, particularly anteriorly. The dorsal fin is in two parts, the first consisting of eight spines and the second of one spine followed by 18 to 21 soft rays. The anal fin consists of two anteriorly detached spines followed by one spine and 15 to 17 soft rays.[14] The pelvic fins contain 1 spine and 19 to 21 soft rays.[15] The caudal fin is strongly forked, and the pectoral fins are falcate, being longer than the length of the head. The lateral line has a pronounced and moderately long anterior arch, with the curved section intersecting the straight section below the lobe of the second dorsal fin. The curved section of the lateral line contains 58-64 scales,[15] while the straight section contains none to four scales and 26 to 38 very strong scutes. The chest is devoid of scales with the exception of a small patch of scales in front of the pelvic fins.[16] The upper jaw contains a series of strong outer canines with an inner band of smaller teeth, while the lower jaw contains a single row of conical teeth. The species has 20 to 24 gill rakers in total and 24 vertebrae are present.[12] The eye is covered by a moderately well-developed adipose eyelid, and the posterior extremity of the jaw is vertically under or just past the posterior margin of the pupil.[12] The eye of the giant trevally has a horizontal streak in which ganglion and photoreceptor cell densities are markedly greater than the rest of the eye. This is believed to allow the fish to gain a panoramic view of its surroundings, removing the need to constantly move the eye, which in turn will allow easier of detection of prey or predators in that field of view.[17]

At sizes less than 50 cm, the giant trevally is a silvery-grey fish, with the head and upper body slightly darker in both sexes.[18] Fish greater than 50 cm show sexual dimorphism in their colouration, with males having dusky to jet-black bodies, while females are a much lighter coloured silvery-grey.[18] Individuals with darker dorsal colouration often also display striking silvery striations and markings on the upper part of their bodies, particularly their backs.[10] Black dots of a few millimetres in diameter may also be found scattered all over the body, although the coverage of these dots varies between widespread to none at all. All the fins are generally light grey to black, although fish taken from turbid waters often have yellowish fins, with the anal fin being the brightest.[12] The leading edges and tips of the anal and dorsal fins are generally lighter in colour than the main part of the fins. There is no black spot on the operculum.[14] Traces of broad cross-bands on the fish's sides are occasionally seen after death. The fishes have been known to prey and eat on the dead fish.[19]

Distribution

The giant trevally is widely distributed throughout the tropical and subtropical waters of the Bay of Bengal, Indian and Pacific Oceans, ranging along the coasts of three continents and many hundreds of smaller islands and archipelagos.[12] In the Indian Ocean, the species' westernmost range is the coast of continental Africa, being distributed from the southern tip of South Africa[20] north along the east African coastline to the Red Sea and Persian Gulf. Its range extends eastwards along the Asian coastline, including Pakistan, India and into Southeast Asia, the Indonesian Archipelago and northern Australia.[6] The southernmost record from the west coast of Australia comes from Rottnest Island,[21] not far offshore from Perth. Elsewhere in the Indian Ocean, the species has been recorded from hundreds of small island groups, including the Maldives, Seychelles, Madagascar and the Cocos (Keeling) Islands.[6]

The giant trevally is abundant in the central Indo-Pacific region, found throughout all the archipelagos and offshore islands including Indonesia, Philippines and Solomon Islands. Along continental Asia, the species has been recorded from Malaysia to Vietnam, but not China.[6] Despite this, its offshore range does extend north to Hong Kong, Taiwan and southern Japan.[12][15] In the south, the species reaches as far south as New South Wales in Australia[21] and even to the northern tip of New Zealand in the southern Pacific. Its distribution continues throughout the western Pacific, including Tonga, Western Samoa and Polynesia, with its easternmost limits known to be the Pitcairn and Hawaiian Islands.[11][16]

Habitat

The giant trevally inhabits a very wide range of offshore and inshore marine environments, with the species also known to tolerate the low salinity waters of estuaries and rivers. It is a semipelagic fish known to spend time throughout the water column, but is mostly demersal in nature.[22] The species is most common in shallow coastal waters in a number of environments, including coral and rocky reefs and shorefaces, lagoons, embayments, tidal flats and channels. They commonly move between reef patches, often over large expanses of deeper sand and mud bottoms between the reefs.[23][24] Older individuals tend to move to deeper seaward reefs, bomboras and drop-offs away from the protection of fringing reefs, often to depths greater than 80 m.[25][26] Large individuals, however, often return to these shallower waters as they patrol their ranges, often to hunt or reproduce.[26] In Hawaii, the juvenile to subadult giant trevally is the most common large carangid in the protected inshore waters, with all other species apparently preferring the outer, less protected reefs.[27] It is also easily attracted to artificial reefs, where studies have found it to be one of the predominant species around these structures in Taiwan.[28]

Juvenile to subadult giant trevally are known to enter and inhabit estuaries, the upper reaches of rivers and coastal lakes in several locations, including South Africa,[29] Solomon Islands,[30] Philippines,[31] India,[32] Taiwan,[33] Thailand,[34] northern Australia,[35] and Hawaii.[23] In some of these locations, such as Australia, it is a common and relatively abundant inhabitant,[30] while in others, including South Africa and Hawaii, it is much rarer in estuaries.[23] The species has a wide salinity tolerance, as evident from the ranges from which juvenile and subadult fish in South African estuaries have been recorded; 0.5 to 38 parts per thousand (ppt),[36] with other studies also showing tolerance levels of less than 1 ppt.[29] In these estuaries, the giant trevally is known from both highly turbid, dirty water to clean, high visibility waters, but in most cases, the species prefers the turbid waters.[23] Younger fish apparently actively seek out these turbid waters, and when no estuaries are present, they live in the turbid inshore waters of bays and beaches. These young fish eventually move to inshore reefs as they mature, before again moving to deeper outer reefs.[27]

In the Philippines, a population of giant trevally inhabit (and were once common in) the landlocked fresh waters of the formerly saltwater Taal Lake, and are referred to as maliputo to distinguish them from the marine variant (locally named talakitok). Along with Taal Volcano and Taal Lake, the maliputo is prominently featured on the reverse side of the newly redesigned Philippine 50 peso bill.[37]

Biology and ecology

The giant trevally is a solitary fish once it reaches sexual maturity,[20] only schooling for the purposes of reproduction and more rarely for feeding.[22] Juveniles and subadults commonly school, both in marine and estuarine environments. Observations from South African estuaries indicate the schools of smaller juveniles tend not to intermingle with schools of other species, but larger subadults are known to form mixed-species schools with the brassy trevally.[36] Research has been conducted on the movements of larger fish around their habitats, as well as the movement between habitats as the species grows, to understand how marine reserves impact on the species. Adult giant trevally are known to range back and forth up to 9 km along a home range, with some evidence of diel and seasonal shifts in habitat use.[26] In the Hawaiian Islands, giant trevally do not normally move between atolls, but have specific core areas where they spend most their time. Within these core areas, habitat shifts during different times of the day have been recorded, with the fish being most active at dawn and dusk, and usually shifting location near sunrise or sunset.[26] Furthermore, large seasonal migrations appear to occur for the purpose of aggregating for spawning, with this also known from the Solomon Islands.[38] Despite not moving between atolls, they do make periodic atoll-wide journeys of up to 29 km.[26] Long-term studies show juveniles can move up to 70 km away from their protected habitats to outer reefs and atolls.[24] The giant trevally is one of the most important apex predators in its habitats, both as adults on reefs and as juveniles in estuaries.[35] Observations in relatively untouched waters of the northwestern Hawaiian Islands showed the giant trevally was of high ecological importance, constituting 71% of the apex predator biomass, and was the dominant apex predator. This number is considerably less in heavily fished Hawaiian waters.[39] The species is prey to sharks, especially when small. Conversely, adult giant trevallies, either singles or pairs, have been recorded attacking sharks (like blacktip reef shark) by ramming them repeatedly with their head. The shark, sometimes even larger than the trevally, may die from the attack. The reason for this behavior is unclear, but the giant trevally does not attempt to eat the dead shark. Rarely, they have been recorded behaving in the same way towards humans: A spearfisher in Hawaii broke three ribs when rammed by a giant trevally.[40][41] Large giant trevallies have been recorded as a host of the sharksucker, Echeneis naucrates, a fish which is normally seen attached to the undersides of sharks.[42]

Diet and feeding

The giant trevally is a powerful predatory fish, from the estuaries it inhabits as a juvenile to the outer reefs and atolls it patrols as an adult.[22][23] Hunting appears to occur at different times of the day in different areas of its range; off South Africa it is most active during the day, especially at dawn and dusk,[20] while off Zanzibar and Hong Kong, it is nocturnal in its habits.[43][44] The species' diets have been determined in several countries and habitats; their diets generally vary slightly by locations and age. In all but one study (which was of juveniles), the giant trevally dominantly takes other fishes, with various crustaceans, cephalopods and occasionally molluscs making the remainder of the diet.[11][45] In Hawaii, the species has a predominantly fish-based diet consisting of Scaridae and Labridae, with crustaceans, including lobsters, and cephalopods (squid and octopus) making up the remaining portion. The large number of reef fishes suggests it spends much of its time foraging over shallow-water reef habitats, but the presence of squid and the schooling carangid Decapterus macarellus indicates exploitation of more open-water habitats, as well.[22] Off Africa, the diet is similar, consisting mostly of fish including eels, with minor squid, octopus, mantis shrimp, lobsters and other crustaceans.[43] Younger fish inside Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii showed the only instance where crustaceans were preferred over fish; stomatopods, shrimp and crabs were the most common prey taken at 89% of stomach content by volume, with fish, mostly of the family Blennidae, making up only 7% of the stomach contents.[27] Estuarine fish in both Hawaii and Australia have mostly fish-based diets, with crustaceans such as prawns and amphipods also of importance, and they are known to take more novel prey, such as spiders and insects, in these habitats.[23][46] Juvenile turtles and dolphins were reported being found within the stomach contents of larger giant trevally.[47] Studies of different size classes of fish have found their diets change with age in some locations, with the changes relating to an increased volume of fish taken.[36]

Giant trevally also feed on fledgling sooty terns on Farquhar Atoll snatching them from the water surface and even jumping acrobatically to catch them in the air as seen on the BBC documentary Blue Planet II, episode 1.[48] So far this behaviour has not been observed elsewhere.

Studies in controlled environments on the giant trevally's feeding strategies have found hunting in schools increases their capture efficiency, but is not necessary for an individual's survival. When a school is formed during feeding, one individual will take a leading position, with others trailing behind it. Several individuals will attack the prey school, striking and stunning the prey, with the leading individual generally being more successful. Some individuals act individually and opportunistically within the school if one of the prey fish becomes isolated, with the main advantage of schooling appearing to be the ability to further break up and isolate prey schools. The only time hunting in schools is a disadvantage is when only isolated prey are present, such as close to a reef; here, an individual hunter has a greater probability of capturing it than if a group is present.[49] Another hunting strategy of the giant trevally is to 'escort' monk seals, a behavior which has been observed near the Hawaiian Islands. The trevally swim close by the seal, and when the seal stops to forage, the trevally positions its mouth inches away from the seal. If a prey item is disturbed, the trevally will attempt to steal the prey from the seal, which routinely does occur. The seal does not appear to gain any benefit from this relationship, and it is thought juvenile seals being followed in this way may be outcompeted by the larger fish.[50] A similar strategy has been employed by fish in the presence of large reef sharks, as they use the larger animal as a tool to ambush prey.[47] The opportunistic nature of giant trevally has also been made evident by studies on the mortality rate of undersized or egg-bearing lobsters released from traps at the water's surface of the Hawaiian Islands. The fish are efficient predators of these crustaceans, with individuals often seizing a lobster before it could sink to the seafloor after being released, or attacking before the lobster moves into a defensive position. Some bolder, large individuals are even known to eat the lobster head first when it is in a defensive stance.[51]

Life history

The giant trevally reaches sexual maturity at 54 to 61 cm in length and three to four years of age,[43] although many authors narrow this down to 60 cm and three years of age.[20] Sex ratio estimates from the Hawaiian Islands suggest the population is slightly skewed toward females, with the male:female ratio being 1:1.39.[22] Spawning occurs during the warmer months in most locations, although the exact dates differ by location. In southern Africa, this occurs between July and March, with a peak between November and March;[43] in the Philippines between December and January, with a lesser peak during June;[52] and in Hawaii between April and November, with a major peak during May to August.[22] Lunar cycles are also known to control the spawning events, with large schools forming in certain locations at specific phases of the moon in Hawaii and the Solomon Islands.[26][38] Locations for spawning include reefs, the reef channels and offshore banks.[44] Sampling of schools prior to spawning suggests the fish segregate into schools of only one sex, although the details are still unclear.[43] Observations in the natural habitat found spawning occurred during the day immediately after and just before the change of tide when there were no currents. Giant trevally gathered in schools of over 100 individuals, although ripe individuals occurred slightly deeper; around 2–3 m above the seabed in groups of three or four, with one silver female being chased by several black males.[52] Eventually, a pair would sink down to a sandy bottom, where eggs and sperm were released. The fish then diverged and swam away. Each individual appears to spawn more than once in each period, with only part of the gonads ripe in spawners. Fecundity is not known, although females are known to release several thousand eggs on capture during the spawning process. Eggs are described as pelagic and transparent in nature.[52]

The giant trevally's early larval stages and their behaviour have been extensively described, with all fins having formed by at least 8 mm in length, with larvae and subjuveniles being silver with six dark vertical bars.[25] Laboratory populations of fish show a significant variability in the length at a certain age, with the average range being around 6.5 mm. Growth rates in larvae between 8.0 and 16.5 mm are on average 0.36 mm per day. The speed at which larvae swim increases with age from 12 cm/s at 8 mm in length to 40 cm/s at 16.5 mm, with size rather than age a better predictor of this parameter.[25] Size is also a better predictor of endurance in larvae than age. These observations suggest the species becomes an effective swimmer (is able to swim against a current) around 7–14 mm. No obvious relationships with age and either swimming depth or trajectory have been found. Larvae appear to also opportunistically feed on small zooplankton while swimming. The larvae actively avoid other large fish, and jellyfish are occasionally used as temporary cover. Larvae have no association with reefs, and appear to prefer to live pelagically.[25] Daily growth is estimated at between 3.82 and 20.87 g/day, with larger fish growing at a more rapid rate. Length at the age of one year is 18 cm, at two years is 35 cm and by three years, the fish is around 50 to 60 cm.[22] The use of von Bertalanffy growth curves fitted to observed otolith data show an individual of around 1 m in length is about eight years old, while a 1.7 m fish would be around 24 years old. The maximum theoretical length of the species predicted by the growth curves is 1.84 m,[22] but the largest reported individual was 1.7 m long. As previously mentioned, as the giant trevally grows, it shifts from turbid inshore waters or estuaries to reefs and lagoons in bays, moving finally to outer reefs and atolls.[24] A hybrid of C. ignobilis and C. melampygus (bluefin trevally) has been recorded from Hawaii. The specimen was initially thought to be a bluefin trevally of world-record size, but was later rejected when it was discovered to be a hybrid. Initial evidence of hybridisation was morphological characteristics intermediate to the two species; later genetic tests confirmed it was indeed a hybrid. The two species are known to school together, including at spawning time, which was considered to be the reason for hybridisation.[53]

Relationship to humans

The giant trevally has been used by humans since prehistoric times, with the oldest known records of the capture of this species by Hawaiians, whose culture held the fish in high regard. The ulua, as the fish is known to Hawaiians, was likened to a fine man and strong warrior, which was the cause of a ban on women eating the species in antiquity.[54] The species was often used in Hawaiian religious rites, and took place of a human sacrifice when none was available. Culturally, the fish was seen as a god, and treated as gamefish which commoners could not hunt. There are many mentions of ulua in Hawaiian proverbs, all generally relating to the strength and warrior-like qualities of the fish.[13] The Hawaiians considered the fish to be of excellent quality, with white, firm flesh. Despite this, intrusions of giant trevally into modern-day fishponds used by Hawaiians for rearing fish are unwelcome; being a predator, it eats more than it is worth at market.[54]

The giant trevally is of high importance to modern fisheries throughout its range, although quantifying the amounts taken is very difficult due to the lack of fishery statistics kept in most of these countries. Hawaii has the best-kept statistics, where the 1998 catch consisted of 10,194 pounds of giant trevally worth around US$12,000.[13] Historically, the species has been taken in far greater numbers, and has been an important food, market and game fish since the early 1900s. However, their exploitation has seen the landings of the species decrease by over 84% since the turn of the century, declining from 725,000 lb to 10,000 lb in recent catches.[55] FAO statistics of the Asian region record catches between 4,000 and 10,000 tonnes between 1997 and 2007,[56] although this excludes most fisheries which are not monitored or do not discriminate between trevally species. The giant trevally is commercially caught by a number of methods, including hook and line, handlines, gill nets and other types of artisanal traps. The species has also successfully been bred for aquaculture purposes in Taiwan.[57] It is sold at market fresh, frozen, salted, and smoked, and as fishmeal and oil.[12]

The giant trevally is considered one of the top gamefish of the Indo-Pacific region, having outstanding strength, speed and endurance once hooked.[10] It can be taken by many methods, including baits of cut or live fish and squid, as well as a wide array of lures. The species is commonly taken on bibbed plugs, minnows, spoons, jigs and poppers, soft plastic lures and saltwater flies.[58] In recent years, the development of both jigging and surface-popping techniques has seen the giant trevally become an extremely popular candidate for catch and release fishing,[10] with many charter operators based around this concept.[47] The species is also popular with spearfishermen throughout its range. The species' edibility has been rated from poor to excellent by different authors, although numerous cases of ciguatera poisoning have been reported from the species.[59] Detailed tests on a large (1 m) specimen taken from Palmyra Island showed the toxicity of the fish's flesh, liver and washed intestinal tract produced no or weakly positive symptoms to laboratory mice, but the digested contents of the intestine were lethal. The authors argued, based on this test, the flesh of giant trevally was safe to consume. However, analysis of case studies in which ciguatera poisoning was reported after eating the fish suggested an accumulative effect occurs with repeated consumption; and tests like the one outlined above are not reliable, as the toxin appears to be distributed haphazardly throughout each fish.[59] Since 1990, giant trevally taken from the main Hawaiian islands have been blocked from sale by auction internationally due to concerns over liability from ciguatera poisoning.[13]

Conservation

A decline in giant trevally numbers around inhabited regions has been well documented in Hawaii, with both catch data as presented above and ecological studies showing this decrease in numbers. A biomass study in the Hawaiian Islands indicates the main Hawaiian Islands are heavily depleted in the species, which in untouched ecosystems comprises 71% of the apex predator biomass. In contrast, it comprises less than 0.03% of the apex biomass in exploited habitats, with only a single fish observed during the course of this research study.[39] Prior to this, a 1993 report suggested the population around the main Hawaiian islands were not stressed, though several biological indicators suggested to the contrary. This was due to the highly size-selective nature of the fishery, which theoretically should prevent a decrease in numbers.[60] Despite this, populations have decreased, and in light of their continued falling abundance in Hawaii, several recommendations, including banning the commercial take of the species, increasing minimum lengths and decreasing bag limits for anglers, as well as reassessment of protected areas for the species, have been proposed by officials.[13] The species (nor any other carangid) has not been assessed by the IUCN.

Some recreational fishing groups are also promoting a catch and release practice for the giant trevally, with this becoming an increasingly popular option for charter boat operators, who have also begun to tag giant trevally for scientific purposes.[61] At large sizes, the species is more likely to be ciguatoxic, so if the fish is kept, it must be disposed of or sent to a taxidermist if it is a trophy fish. A catch and release approach has also been adopted by operators outside Hawaii, with Australian operators who target the species by popping and jigging rarely keeping any fish.[10] Careful fish handling techniques have also been implemented by anglers so as not to damage the fish; such techniques include supporting the fish's weight, using barbless single, rather than treble, hooks and restricting the time the fish spends out the water to a minimum.[47]

References

- Smith-Vaniz, W.F. & Williams, I. (2016). "Caranx ignobilis (errata version published in 2017)". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species. 2016. doi:10.2305/IUCN.UK.2016-3.RLTS.T20430651A47552431.en.

- Doug Olander (23 March 2015). "Capture of a Giant Trevally Off Panama Makes History". Retrieved 19 June 2016.

- J. S. Nelson; T. C. Grande; M. V. H. Wilson (2016). Fishes of the World (5th ed.). Wiley. pp. 380–387. ISBN 978-1-118-34233-6.

- Hosese, D.F.; Bray, D.J.; Paxton, J.R.; Alen, G.R. (2007). Zoological Catalogue of Australia Vol. 35 (2) Fishes. Sydney: CSIRO. p. 1150. ISBN 978-0-643-09334-8.

- MyEtymology (2008). "Etymology of the Latin word ignobilis". Retrieved 2009-09-17.

- Froese, Rainer and Pauly, Daniel, eds. (2009). "Caranx ignobilis" in FishBase. September 2009 version.

- Smith-Vaniz, W.F.; K.E. Carpenter (2007). "Review of the crevalle jacks, Caranx hippos complex (Teleostei: Carangidae), with a description of a new species from West Africa" (PDF). Fisheries Bulletin. 105 (4): 207–233. Retrieved 2009-04-07.

- California Academy of Sciences: Ichthyology (September 2009). "Caranx ignobilis". Catalog of Fishes. CAS. Retrieved 2009-05-31.

- Jenkins, O.P. (1903). "Report on collections of fishes made in the Hawaiian Islands, with descriptions of new species". Bulletin of the U.S. Fish Commission. 22: 415–511.

- Knaggs, B. (2008). Knaggs, B. (ed.). "12 Rounds with Trevally". Saltwater Fishing. Silverwater, NSW: Express Publications (58): 72–80.

- Honebrink, Randy R. (2000). "A review of the biology of the family Carangidae, with emphasis on species found in Hawaiian waters" (PDF). DAR Technical Report. Honolulu: Department of Land and Natural Resources. 20-01: 1–43. Retrieved 2009-05-11.

- Smith-Vaniz, W. (1999). "Carangidae" (PDF). In Carpenter, K.E.; Niem, V.H. (eds.). The living marine resources of the Western Central Pacific Vol 4. Bony fishes part 2 (Mugilidae to Carangidae). FAO species identification guide for fishery purposes. Rome: FAO. pp. 2659–2757. ISBN 92-5-104301-9.

- Rick Gaffney & Associates, Inc. (2000). "Evaluation of the status of the recreational fishery for ulua in Hawai'i, and recommendations for future management" (PDF). Division of Aquatic Resources Technical Report. Department of Land and Natural Resources, Hawaii. 20-02: 1–42. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Randall, John E. (1995). Coastal Fishes of Oman. University of Hawaii Press. Honolulu. p. 183. ISBN 0-8248-1808-3.

- Lin, Pai-Lei; Shao, Kwang-Tsao (1999). "A Review of the Carangid Fishes (Family Carangidae) From Taiwan with Descriptions of Four New Records". Zoological Studies. 38 (1): 33–68.

- Allen, G.R.; D.R. Robertson (1994). Fishes of the tropical eastern Pacific. University of Hawaii Press. p. 332. ISBN 978-0-8248-1675-9.

- Collin, S.P.; Shand, J. (2003). "8". In Collin, S.P.; Marshall, N.J. (eds.). Retinal sampling and the visual field in fishes. Springer. pp. 139–160. ISBN 978-0-387-95527-8.

- Talbot, F. H.; Williams, F. (1956). "Sexual colour differences in Caranx ignobilis (Forsk.)". Nature. 178 (4539): 934–5. Bibcode:1956Natur.178..934T. doi:10.1038/178934a0. PMID 13369587.

- Nichols, J.T. (1936). "On Caranx ignobilis (Forskål)". Copeia. 1936 (2): 119–120. doi:10.2307/1436667. JSTOR 1436667.

- van der Elst, Rudy; Peter Borchert (1994). A Guide to the Common Sea Fishes of Southern Africa. New Holland Publishers. p. 142. ISBN 1-86825-394-5.

- Hutchins, B.; Swainston, R. (1986). Sea Fishes of Southern Australia: Complete Field Guide for Anglers and Divers. Melbourne: Swainston Publishing. p. 187. ISBN 1-86252-661-3.

- Sudekum, A.E.; Parrish, J.D.; Radtke, R.L.; Ralston, S. (1991). "Life History and Ecology of Large Jacks in Undisturbed, Shallow, Oceanic Communities" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 89 (3): 493–513. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Smith, G.C.; Parrish, J.D. (2002). "Estuaries as Nurseries for the Jacks Caranx ignobilis and Caranx melampygus (Carangidae) in Hawaii". Estuarine, Coastal and Shelf Science. 55 (3): 347–359. Bibcode:2002ECSS...55..347S. doi:10.1006/ecss.2001.0909.

- Wetherbee, B.M.; Holland, K.N.; Meyer, C.G.; Lowe, C.G. (2004). "Use of a marine reserve in Kaneohe Bay, Hawaii by the giant trevally, Caranx ignobilis". Fisheries Research. 67 (3): 253–263. doi:10.1016/j.fishres.2003.11.004.

- Leis, J.M.; A.C. Hay; D.L. Clark; I.-S.Chen; K.-T. Shao (2006). "Behavioral ontogeny in larvae and early juveniles of the giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) (Pisces: Carangidae)" (PDF). Fishery Bulletin. 104 (3): 401–414. Retrieved 2009-09-14.

- Meyer, C.G.; Holland, K.N.; Papastamatiou, Y.P. (2007). "Seasonal and diel movements of giant trevally Caranx ignobilis at remote Hawaiian atolls: implications for the design of Marine Protected Areas". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 333: 13–25. Bibcode:2007MEPS..333...13M. doi:10.3354/meps333013.

- Meyer, Carl G.; Kim N. Holland; Bradley M. Wetherbee; Christopher G. Lowe (2001). "Diet, resource partitioning and gear vulnerability of Hawaiian jacks captured in fishing tournaments". Fisheries Research. 53 (2): 105–113. doi:10.1016/S0165-7836(00)00285-X.

- Lin, J.-C.; Su, W.-C. (1994). "Early phase of fish habitation around a new artificial reef off southwestern Taiwan". Bulletin of Marine Science. 55 (2–3): 1112–1121.

- Blaber, S.J.M. (1997). Fish and fisheries of tropical estuaries. Chapman and Hall Fish and Fisheries Series. 22. Springer. p. 367. ISBN 978-0-412-78500-9.

- Blaber, S.J.M.; Milton, D.A. (1990). "Species composition, community structure and zoogeography of fishes of mangrove estuaries in the Solomon Islands". Marine Biology. 105 (2): 259–267. doi:10.1007/BF01344295.

- Bleher, Heiko (1996). "Bombon". Aqua Geographia. 12 (4): 6–34.

- Rao, K.V.R. (1995). In Fauna of Chilka Lake: Wetland Ecosystem Series 1. India: Zoological Survey of India. pp. 483–506.

- Kuo, S.-R.; K.-T. Shao (1999). "Species composition of fish in the coastal zones of the Tsengwen estuary, with descriptions of five new records from Taiwan" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 38 (4): 391–404. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2008-12-04. Retrieved 2008-12-15.

- Fish Team of the Trang Project (2002). Illustrated fish fauna of a mangrove estuary at Sikao, southwestern Thailand. Trang and Tokyo: Trang Project for Biodiversity and Ecological Significance of Mangrove Estuaries in Southeast Asia, Rajamangala Institute of Technology and the University of Tokyo. pp. 60p.

- Blaber, S.J.M. (1986). "Feeding Selectivity of a Guild of Piscivorous Fish in Mangrove Areas of North-west Australia". Australian Journal of Marine and Freshwater Research. 37 (3): 329–336. doi:10.1071/MF9860329.

- Blaber, S.J.M.; Cyrus, D.P. (1983). "The biology of Carangidae (Teleostei) in Natal estuaries". Journal of Fish Biology. 22 (2): 173–188. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1983.tb04738.x.

- Agcaoili, Lawrence (2010-12-17). "Aquino, BSP launch new generation of bank notes". The Philippine Star. p. 1. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- Hamilton, R.; R. Walter (1999). "Indigenous ecological knowledge and its role in fisheries research design: A case study from Roviana Lagoon, Western Province, Solomon Islands" (PDF). SPC Traditional Marine Resource Management and Knowledge Information Bulletin. 11: 13–25. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-06-11. Retrieved 2009-05-21.

- Friedlander, A.M.; DeMartini, E.E. (2002). "Contrasts in density, size, and biomass of reef fishes between the northwestern and the main Hawaiian islands: the effects of fishing down apex predators". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 230: 253–264. Bibcode:2002MEPS..230..253F. doi:10.3354/meps230253.

- D.L. McPherson; K.V. Blaiyok; W.B. Masse (2012). "Lethal Ramming of Sharks by Large Jacks (Carangidae) in the Palau Islands, Micronesia". Pacific Science. 66 (3): 327–333. doi:10.2984/66.3.6.

- Helfman, G. (22 March 2012). "Wild Thing: Turning the tables on the sharks in the gray suits". Johns Hopkins University Press. Retrieved 27 May 2019.

- Brunnschweiler, J.M.; Sazima, I. (2006). "A new and unexpected host for the sharksucker (Echeneis naucrates) with a brief review of the echeneid–host interactions". Marine Biodiversity Records. 1 (e41): 1–3. doi:10.1017/S1755267206004349. S2CID 55868607.

- Williams, F. (1965). "Further notes on the biology of the East African pelagic fishes of the Families Carangidae and Sphyraenidae". Journal of East African Agriculture and Forestry. 31 (2): 141–168. doi:10.1080/00128325.1965.11662035.

- Sadovy, Yvonne; Andrew S. Cornish (2001). Reef Fishes of Hong Kong. Hong Kong University Press. p. 321. ISBN 978-962-209-480-2.

- Potts, G.W. (1981). "Behavioural interactions between the Carangidae (Pisces) and their prey on the fore-reef slope of Aldabra, with notes on other predators". Journal of Zoology. 195 (3): 385–404. doi:10.1111/j.1469-7998.1981.tb03472.x.

- Baker, R.; Sheaves, M. (2005). "Redefining the piscivore assemblage of shallow estuarine nursery habitats". Marine Ecology Progress Series. 291: 197–213. Bibcode:2005MEPS..291..197B. doi:10.3354/meps291197.

- Wyrsta, L. (2007). "giant-trevally.com". Species Information. Retrieved 2009-09-23.

- Attenborough, David (29 October 2017). ""One Ocean"". Blue Planet II. Episode 1. BBC One.

- Major, P.F. (1978). "Predator-prey interactions in two schooling fishes, Caranx ignobilis and Stolephorus purpureous". Animal Behaviour. 26 (3): 760–777. doi:10.1016/0003-3472(78)90142-2.

- Parrish, F.A.; Marshall, G.J.; Buhleier, B.; Antonelis, G.A. (2008). "Foraging interaction between monk seals and large predatory fish in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands". Endangered Species Research. 4: 299–308. doi:10.3354/esr00090.

- Gooding, R.M. (1985). "Predation on Released Spiny Lobster, Panulirus marginatus, During Tests in the Northwestern Hawaiian Islands". Marine Fishery Reviews. 47 (1): 27–35.

- von Westernhagen, H. (1974). "Observations on the natural spawning of Alectis indicus (Ruppell) and Caranx ignobilis (Forsk.) (Carangidae)". Journal of Fish Biology. 6 (4): 513–516. doi:10.1111/j.1095-8649.1974.tb04567.x.

- Murakami, K.; S.A. James; J.E. Randall; A.Y. Suzumoto (2007). "Two Hybrids of Carangid fishes of the Genus Caranx, C. ignobilis x C. melampygus and C. melampygus x C. sexfasciatus, from the Hawaiian Islands" (PDF). Zoological Studies. 46 (2): 186–193. Retrieved 2007-05-14.

- Wyban, C. A. (1992). "Chapter 3. The Ecosystem". Tide and Current: fishponds of Hawai'i. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 34–35. ISBN 978-0-8248-1396-3.

- Shomura, R. S. (1987). Hawai'i's Marine Fishery Resources: yesterday (1900) and today (1986). H-87-21. Honolulu: SWFSC Administrative Report.

- Fisheries and Agricultural Organisation. "Global Production Statistics 1950-2007". Giant Trevally. FAO. Retrieved 2009-05-19.

- Yu, N.-H. (2002). New Challenges: breeding species in Taiwan, VIII. Kaohsiung, Taiwan: Fish Breeding Association of the Republic of China. p. 52.

- Starling, S. (1988). The Australian Fishing Book. Hong Kong: Bacragas Pty. Ltd. p. 488. ISBN 0-7301-0141-X.

- Goe, D. R.; Halstead, B. W. (1955). "A Case of Fish Poisoning from Caranx ignobilis Forskål from Palmyra Island, with Comments on the Sensitivity of the Mouse-Injection Technique for the Screening of Toxic Fishes". Copeia. 1955 (3): 238–240. doi:10.2307/1440472. JSTOR 1440472.

- Kobayashi, D. R. (1993). "Natural mortality rate and fishery characterisation for white ulua (Caranx ignobilis) in the Hawaiian Islands". Southwest Fisheries Science Center Administrative Report. NOAA. H-93-02: 1–22.

- Department of Land and Natural Resources (2007). "Ulua tagging project" (PDF). State of Hawaii. pp. 1–20. Retrieved 2009-09-25.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Giant trevally. |

- Giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) at FishBase

- Giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) at Australian Museum Online

- Giant trevally (Caranx ignobilis) at giant-trevally.com

- Photos of Giant trevally on Sealife Collection