Kaurna

The Kaurna (also Coorna, Kaura, Gaurna and other variations) people are a group of Aboriginal people whose traditional lands include the Adelaide Plains of South Australia. The word "Kaurna" is pronounced in English as /ˈɡɑːnə/; and in the traditional language as [ɡ̊auɳa]. They were known as the Adelaide tribe by the early settlers. Kaurna culture and language were almost completely destroyed within a few decades of the British colonisation of South Australia in 1836. However, extensive documentation by early missionaries and other researchers has enabled a modern revival of both language and culture.

Etymology

The early settlers of South Australia referred to the various indigenous tribes of the Adelaide Plains and Fleurieu Peninsula as "Rapid Bay tribe", "the Encounter Bay tribe", "the Adelaide tribe", the Kouwandilla tribe, "the Wirra tribe", "the Noarlunga tribe" (the Ngurlonnga band) and the Willunga tribe (the Willangga band).[1]

The extended family groups of the Adelaide Plains, who spoke dialects of a common language, were named according to locality, such as Kawanda Meyunna (North men), Wirra Meyunna (Forest People), Pietta Meyunna (Murrray River people), Wito Meyunna (Adelaide clan's former name), Tandanya (South Adelaide people), etc. – but they had no common name for themselves. The name Kaurna was not recorded until 1879, used by Alfred William Howitt in 1904,[2] but not widely used until popularised by Norman B. Tindale in the 1920s.[3] Most likely, it is an exonym introduced from the Ramindjeri or Ngarrindjeri word kornar meaning "men" or "people".[3]

Language

Kaurna'war:a (Kaurna speech)[4] belongs to the Thura-Yura branch of the Pama–Nyungan languages.[5] The first word lists taken down of the Kaurna language date to 1826.[6] A knowledge of Kaurna language was keenly sought by many of the early settlers. William Williams and James Cronk were the first settlers to gain a working knowledge of the language, and to publish a Kaurna wordlist, which they did in 1840.[7] When George Gawler, South Australia's third Governor, arrived in October 1838, he gave a speech to the local Indigenous population through a translator, William Wyatt, assisted also by Williams and Cronk. Gawler actively encouraged the settlers to learn Kaurna, and advocated using the Kaurna names for geographic landmarks.[8]

Two In October 1838 two German missionaries, Christian Teichelmann and Clamor Schürmann, arrived on the same ship as Gawler in 1838, and immediately set about learning and documenting the language in order to civilise and "Christianise" the natives.[9] In December 1839, they opened a school at Piltawodli (in the west Park Lands north of the River Torrens) where the children were taught to read and write in Kaurna. Schurmann and Teichelmann (and later Samuel Klose[10]) translated the Ten Commandments and a number of German hymns into Kaurna,[11] and although they never achieved their goal of translating the entire Bible, their recorded vocabulary of over 2,000 words was the largest wordlist registered by that time, and pivotal in the modern revival of the language.[12]

Territory

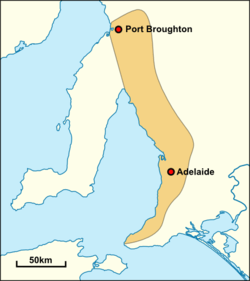

Kaurna territory extended from Cape Jervis at the bottom of the Fleurieu Peninsula to Port Wakefield on the eastern shore of Gulf St Vincent, and as far north as Crystal Brook in the Mid North. Tindale claimed clans were found living in the vicinity of Snowtown, Blyth, Hoyleton, Hamley Bridge, Clarendon, Gawler and Myponga. The stringy bark forests over the back of the Mount Lofty Ranges have been claimed as a traditional boundary between Kaurna and Peramangk people. Tunkalilla Beach (keinari), 20 kilometres (12 mi) east of Cape Jervis, is the traditional boundary with the Ramindjeri.

This is the most widely cited alignment of Kaurna territorial boundaries. However, according to Ronald and Catherine Berndt the neighbouring Ramindjeri tribe assert a historical territory including the whole southern portion of the Fleurieu Peninsula and Kangaroo Island, extending as far north as Noarlunga[13][14] or even the River Torrens.[15] This overlaps a significant portion of the territory claimed by both the Kaurna and the neighbouring Ngarrindjeri to the east. However, linguistic evidence suggests that the aborigines encountered by Colonel Light at Rapid Bay in 1836 were Kaurna speakers.[16] The Berndt's ethnographic study, which was conducted in the 1930s, identified six Ngarrindjeri clans occupying the coast from Cape Jervis to a few kilometres south of Adelaide. Berndt posits that the clans may have expanded along trade routes as the Kaurna were dispossessed by colonists.[14]

A main Kaurna presence was in Tarndanyangga ("red kangaroo place") near the River Torrens and the creeks that flowed into it, an area which became the site of the Adelaide city centre. Kaurna also resided in the suburb of Burnside, and an early settler of the village of Beaumont described the local people thus:

At every creek and gully you would see their wurlies and their fires at night ... often as many as 500 to 600 would be camped in various places ... some behind the Botanic Gardens on the banks of the river; some toward the Ranges; some on the Waterfall Gully.[17]

Dispossession

Although Governors Hindmarsh (1836-1838) and Gawler (1838-1841) had orders to extend the protection of British law to the people and their property, the colonists' interests came first. Their policy of "civilising" and "protecting" the Indigenous people nonetheless assumed a peaceful transfer of land to the settlers. All land was offered up for sale and bought by settlers.[18]

The Lutheran missionaries Christian Teichelmann and Clamor Schurmann studied Kaurna language and culture, and were able to inform the authorities of their exclusive ownership of land inherited through the paternal line. Gawler reserved several areas for the Kaurna people, but the settlers protested and these were subsequently sold or leased. Within ten years, all of the Kaurna and Ramindjeri lands had been occupied. Wild fauna disappeared as European garden practices were introduced and grazing animals destroyed the bulbs, lilies and tubers which the Kaurna had tended for food. Elders no longer had authority; their entire way of life had been undermined.[18]

Population

1790s–1860s

The Kaurna may have numbered several thousand before European contact, but were down to about 700 by the time of the formal establishment of the colony in 1836.[19] Initially, contacts began with the arrival of sealers and whalers in the 1790s.[19] Sealers established themselves on Kangaroo Island as early as 1806, and raided the mainland for Kaurna women, both for the sexual opportunities and the help they could supply in skinning the sealers' prey.[6] Wary of Europeans from their experience with sealers, the Kaurna generally stayed aloof when the first colonists arrived.[20] The timing was important. Summer was a period when the Kaurna traditionally moved from the plains to the foothills, so that the initial settlement of the Adelaide area took place without any conflict.[21]

The population again severely declined upon the arrival of Anglo-European colonial settlers with South Australia Governor Captain John Hindmarsh as Commander-in-chief in December 1836 at Holdfast Bay (now Glenelg). According to an entry in the South Australian Register (30 January 1842), the Kaurna population numbered around 650.[22] They had suffered a serious drop in numbers in the early 1830s (and possibly again in 1889)[2] due to a smallpox epidemic which is thought to have originated in the eastern states and spread along the Murray River as Indigenous groups traded with each other.[23] This devastated their lives in every way.[2] An outbreak of typhoid, due to pollution by Europeans of the River Torrens, lead to many deaths and a rapid population decline, though accurate figures were not recorded.[23] Many contracted other diseases against which they lacked immunity, such as measles, whooping cough, typhus, dysentery and influenza. The groups lost their identities as they merged with others, and the Kaurna and Ramindjeri people were reduced to very few.[24] In the 1840s, Murray River people invaded, stealing women and children, while the government suppressed the Kaurna attempts at self-defence. Some Kaurna moved north to join other tribes.[25]

The Colonisation Commissioners had promised to protect the Aboriginal people and their property as well as making provision for their subsistence, education and advancement,[2] with the post of Protector of Aborigines set up with this aim. William Wyatt was followed by the first official appointment in the role, Matthew Moorhouse, who held the post from 1839 to 1856. He reported in 1840 that many Kaurna were friendly and helpful, and that by 1840, about 150 spoke at least some English. Many Kaurna men, such as Mullawirraburka ("King John") and Kadlitpinna ("Captain Jack") helped the police and new settlers, also sharing their language, culture and beliefs with the missionaries.[26] An early settler in Marryatville, George Brunskill, reported that the "local Blacks" were harmless, did not steal, and returned borrowed items promptly.[27] Much goodwill was shown on both sides, but as the settler numbers grew, their drunkenness, violence, exploitation and failure to practise the reciprocity expected in Aboriginal culture soured the relationships.[28]

After a few incidents involving the executions of Aboriginal men after the murders of settlers, sometimes on flimsy evidence, and a blind eye turned to violence against Indigenous people, the situation escalated. The Maria massacre of shipwrecked people on the Coorong let to further violent clashes and harsh penalties were imposed to protect the settlers. Missionaries Teichelmann and Schurmann, Protector Moorhouse and Sub-Protector Edward John Eyre questioned the use of a foreign legal code against the Indigenous peoples, and Moorhouse complained of police hostility towards Aboriginal people, but Governor George Grey stood firm, and martial law was applied even where there had been little previous contact with the settlers.[29]

Moorhouse and Grey gave up trying to settle the local Aboriginal people as farmers, and discouraged settlement at Pirltawardli. The 1847 Vagrancy Act restricted their free movement.[30] Teichelmann tried to establish an Aboriginal mission settlement at Happy Valley, about 20 kilometres (12 mi) south of Adelaide, but he lacked the means to develop the property or make farming a viable option for the Kaurna.[31] Many Kaurna people worked for the settlers and were well thought of, but the work was seasonal and the rewards inadequate, and their tribal obligations were not understood by their employers. Grey started the use of rations to maintain the peace and to persuade the people to send their children to school.[32]

According to Moorhouse, "almost whole tribes" had disappeared by 1846,[33] and by the 1850s, there were few remaining Kaurna in the Adelaide area. In 1850 the children (mostly from the Murray River area, but including a few Kaurna[34]) at the Native School (which had been on Kintore Avenue since 1846) were transferred to the Poonindie Native Training Institution near Port Lincoln, on the Eyre Peninsula, over 600 kilometres (370 mi) away.[35] Moorhouse resigned as Protector in 1856, and in 1857 the position was abolished.[36]

The Kaurna people had to accept colonial domination more quickly than in other regions, and they mostly chose to co-exist peacefully with the settlers. Most, however, resisted the "civilising" policies of the government and the Christian teachings of the missionaries. Being so small in number by the 1850s, some were absorbed into the neighbouring Narungga or Ngarrindjeri groups, and some married settlers.[24]

1860s–21st century

By 1860 the Kaurna were vastly outnumbered by the colonists, who numbered 117,727. Adults were also relocated from the city to places such as Willunga, Point McLeay, and Point Pearce in the 1860s. In 1888 a German missionary reported that there was "scarcely one remaining".[24] Some of the Kaurna people settled at Point McLeay and Point Pearce married into local families, and full-blood Kaurna still lived at the missions and scattered in the settled districts in the late 19th century, despite the wide belief that the "Adelaide tribe" was extinct by the 1870s.[37]

Rations continued to be supplied in Adelaide and from ration depots in the country. Although the office of Protector was restored in 1861, the government did not play an active role in Aboriginal affairs, leaving their welfare to the missionaries. A Select Committee reported that the race was doomed to extinction. Some Aboriginal people (Kaurna and others) moved around and sometimes visited the city, camping in Botanic Park, then called the Police Paddocks. In 1874, 18 men and women were arrested and charged as "vagrants", and after a 14 days' imprisonment were sent back to Goolwa and Milang. Running battles between the police and similar groups continued for decades.[38]

History books about Adelaide have largely ignored the Aboriginal presence, and Womadelaide is held each year in Botanic Park without acknowledgement of the Aboriginal encampments 150 years ago on the same land. There is a tradition of performing corroborees and dances dating back to the 1840s, including the "Grand Corroboree" at the Adelaide Oval in 1885 and corroborees at the beaches of Glenelg and Henley Beach around the turn of the century. This huge omission in the history books has been described as "strategic forgetting" by anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner.[39]

The last surviving full-blood Kaurna, a woman called Ivaritji (Amelia Taylor or Amelia Savage[40]) died in 1929.[41][lower-alpha 1] Born in Port Adelaide in the 1840s, her name (sometimes spelt Everety or Ivarity) means "gentle, misty rain" in the Kaurna language. Her father, Ityamaitpinna, known as "Rodney", was one of the leaders of the Kaurna and prominent in the early settlers' accounts.[40] She was responsible for identifying locations of cultural significance in the city, such as the lake in the Adelaide Botanic Garden and Victoria Square/Tarndanyangga, and Whitmore Square has been given her name in honour of the prior occupation of the land by the Kaurna people.[42]

Native title

Unlike the rest of Australia, South Australia was not considered to be terra nullius. The enactment of the South Australia Act 1834 which enabled the province of South Australia to be established, acknowledged Aboriginal ownership and stated that no actions could be undertaken that would affect the rights of any Aboriginal natives of the said province to the actual occupation and enjoyment in their own persons or in the persons of their descendants of any land therein now actually occupied or enjoyed by such natives. Although the Act guaranteed land rights under force of law for the Indigenous inhabitants, it was ignored by the South Australian Company authorities and squatters, who interpreted the Act to mean "permanently occupied".[43][44]

In 2000, a group called Kaurna Yerta Corporation[45] lodged a native title claim on behalf of the Kaurna people. The claim covers over 8,000 square kilometres (3,100 sq mi) of land stretching from Cape Jervis to Port Broughton, including the entire Adelaide metropolitan area.[46] The Ramindjeri people contested the southern portion of the original claim.[15] In March 2018 the determination was made and the Kaurna were officially recognised as the traditional owners of the land from "Myponga to Lower Light". An Indigenous Land Use Agreement for the area was finalised on 19 November 2018.[47] The agreement was among the South Australian government, the federal government and the Kaurna people, with formal recognition coming after the Federal Court judgement, 18 years after lodgement. This was the first claim for a first land use agreement to be agreed to in any Australian capital city. The rights cover Adelaide's whole metropolitan area and includes "17 parcels of undeveloped land not under freehold". Some of the land is Crown land, some belongs to the state government and some is private land owned by corporations. Justice Debra Mortimer said it would be "the first time in Australia that there [had] been a positive outcome within the area of (native title) determination”.[48][49]

In 2009, a group called Encompass Technology[50] wrote to the Governor of South Australia on behalf of the Kaurna people, asserting sovereignty over the Marble Hill ruins in the Adelaide Hills, and the Warriparinga Living Kaurna Cultural Centre in Marion, and claiming that they were owed nearly $50 million in rent.[50] The South Australian Government rejected the claim.[51]

Culture

The Kaurna people were a hunter-gatherer society, who changed their dwellings according to climatic conditions: in summer they would camp near the coastal springs fishing for mulloway. With the onset of winter, they would retire to the woodlands, often using hollowed out fallen redgums along creeks, with bark extensions as shelters.[52] Sudden downpours could quench their fires, the maintaining of which was old women's work, with deadly consequences. At times they would have to impose themselves on otherwise despised tribes, such as the Ngaiawang and Nganguruku to trade goods like their cloaks, quartz flints and red ochre in order to obtain firesticks.[53]

Among their customs was the practice of fire-stick farming (deliberately lit bushfires for hunting purposes) in the Adelaide Hills, which the early European settlers spotted before the Kaurna were displaced. These fires were part of a scrub clearing process to encourage grass growth for Emu and Kangaroo.[54] This tradition led to conflict with the colonists as the fires tended to cause considerable damage to farmland. In an official report, Major Thomas O'Halloran claimed the Kaurna also used this as a weapon against the colonists by lighting fires to deliberately destroy fences, survey pegs and to scatter livestock. Due to this regular burning by the time the first Europeans arrived, the foothills' original Stringybark forests had been largely replaced with grassland. Since the late 1960s, restrictions on foothills subdivision and development have allowed regeneration of native trees and bush to a "natural" condition that would not have existed at the time of European occupation.[55]

Artefacts

Items of Kaurna material culture, such as traditional objects, spears, boomerangs and nets etc. are extremely rare. Interest in collecting and conserving Kaurna culture was not common until their display at the 1889 Paris Exhibition spurred an interest in Indigenous culture, by which time the Kaurna traditional culture was no longer practised. Many hundreds of objects were sent to the Paris exhibition and these were never returned to Australia.

The Kaurna collection held by the South Australian Museum contains only 48 items. In September 2002, a Living Kaurna Cultural Centre was opened at Warriparinga in the southern suburbs area of Adelaide.

Tribal organisation

The Kaurna people lived in family groups called bands, who lived in defined territories called pangkarra which were "passed" from father to son upon his initiation. Pangkarra always had access to the coastline and ran extensively inland. The coastline was essential for seafood hunting and the inland territories provided food, clothing and protection for the people during bad weather. The pangkarra were also grouped into larger areas of land called yerta.[lower-alpha 2]

As all the members of a band were related, marriage between a man and a woman within the same band was forbidden. Bands were patrilineal and patrilocal: a woman always lived with her husband's band following her marriage. Each band was also composed of two exogamous moieties, the Karuru and Mattari, which traced their descent matrilineally to an ancestral totemic being. All the children of a marriage would take their mother's moiety as children were considered to have "inherited" their "flesh and blood" from their mothers alone. Marriage within the same moiety was forbidden.[56] Girls became marriageable at puberty, usually around 12 years of age. Conversely, men were only allowed to marry after the age of 25.

Sexual relations were relatively free and uninhibited, regardless of marital status. Kaurna ownership of property was communal; the reproductive organs were seen no differently from any other form of property, and thus adultery was practically ubiquitous. The visitation of men from distant tribes was seen as a good opportunity to enhance the gene pool. The practice of milla mangkondi or wife stealing was also common, for the same reason.[lower-alpha 3] Although this custom was hated by some victims, as arranged marriages were the norm, some women saw it as an opportunity to choose their own partners and actively encouraged a preferred suitor, all Kaurna bands are said to have engaged in the practice regularly.

Rites and mythology

Very little is known of Kaurna rites and mythology as colonial written records are fragmentary and rare. Physically, the Kaurna practised chest scarification and performed circumcision as an initiatory rite and were the southernmost Indigenous language group to do so. Waterfall Gully has been linked to initiation rites.[57]

Historical accounts of Kaurna burial rites are unreliable as any gathering of Kaurna was thought to be for a funeral. As soon as a person died the body was wrapped in the clothes they had worn in life. The body was then placed on a wiralli (crossed sticks that form the radii of a circle) and an inquest was held to determine cause of death. The body was then buried. Children under four years were not buried for some months, but were wrapped and carried by their mothers during the day with the bundle being used as a pillow at night.[58] Burial by bodies of water was common with the use of sandy beaches, sand dunes and banks of rivers. A large number of graves have been found on Glenelg beach and at Port Noarlunga.[59] Similarly, an unusually complex burial at Kongaratti was found. The grave was rectangular and lined with slate, the base was also lined with slate which had been covered with a bed of grass. An elderly woman was lying on her side, draped in a fishing net and wrapped in a Kangaroo skin cloak. The grave was topped with a layer of grass covered by marine sponges.[59]

The Kaurna regard the 35 miles from the Mount Lofty Ranges to Nuriootpa as the body of a giant who was killed there after attacking their tribe. The peaks of the Mount Lofty Ranges and Mount Bonython are jureidla (conserved in the toponym Uraidla), namely his "two ears".[60]

A legend recounted variously by Unaipon and Milerum concerns a culture hero called Tjilbruke[61] has topographical features that locate it in Kaurna territory. In Tindale's version Tjilbruke is associated with the glossy ibis; the name actually refers to the blue crane.[62] The "Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks" have been mapped from the Bedford Park area (Warriparinga), down the Fleurieu Peninsula, and efforts have been made to preserve and commemorate it where possible.[63]

Munaitjerlo is an ancestral being who created the Moon and stars before himself becoming the Sun. The word Munaitjerlo was believed by Teichelmann to also refer to the Kaurna Dreamtime itself. The mythology of the Mura-Muras, ancestral beings who created landscape features and introduced laws and initiation, can be found in southwest Queensland, the Northern Territory and in the Flinders Ranges through to Eyre Peninsula in South Australia. As it is known that the Kaurna shared a common Dreaming with these peoples it is likely they shared the Mura-Muras as well. By way of contrast, the travels of Tjilbruke are well known from Norman Tindales research.[59]

Kaurna place names

Many places around Adelaide and the Fleurieu Peninsula have names either directly or partially derived from Kaurna place names, such as Cowandilla, Aldinga, Morialta and Munno Para. Some were the names of the Kaurna bands who lived there. There are also a few Kaurna names hybridised with European words.[64]

The Adelaide City Council began the process of dual naming all of the city squares, each of the parks making up the parklands which surround the Adelaide city centre and North Adelaide, and other sites of significance to the Kaurna people in 1997.[65] The naming process, which assigned an extra name in the Kaurna language to each place, was mostly completed in 2003,[66] and the renaming of 39 sites finalised and endorsed by the council in 2012.[67]

Alternative names

- "Adelaide tribe."

- Coorna

- Jaitjawar:a ("our own language").

- Koornawarra

- Kurumidlanta (Pangkala term, lit. "evil spirits").

- Medaindi (horde living near Glenelg), Medaindie.

- Meljurna. ("quarrelsome men", likewise used of northern Kaurna hordes).

- Merelde (Ramindjeri term applied most frequently to the Peramangk but also to the Kaurna).[22]

- Merildekald (Tanganekald term also loosely given to Peramangk)

- Meyu (meju = man)

- Midlanta (Pangkala exonym for the Kaurna).

- Milipitingara

- Nantuwara. ("Kangaroo speakers," applied to northerly hordes).

- Nantuwaru

- Nganawara

- Padnaindi (horde name), Padnayndie,

- Wakanuwan (Jarildekald term for Kaurna and also other tribes such as the Ngaiawang).

- Warra (means "speech" a name for language), Warrah, Karnuwarra ("hills language," a northern dialect, presumably that of Port Wakefield).

- Widninga. (Ngadjuri term applied to Kaurna of Port Wakefield and Buckland Park)

- Winaini. (horde north of Gawler).

- Winnaynie

Repatriation of remains

On 1 August 2019, the remains of 11 Kaurna people were laid to rest at a ceremony led by elder Jeffrey Newchurch at Kingston Park Coastal Reserve, south of Adelaide. John Carty, Head of Humanities at the South Australian Museum, said that the museum was "passionate" about working with the Kaurna people to repatriate their ancestors, and would also be helping to educate the community about what it means to Aboriginal people. The Museum continues to receive further remains, and together with the community would need to find a good solution to accommodate the many remains of Old People, such as a memorial park.[68]

See also

- History of Adelaide

- Matthew Moorhouse

- Pirltawardli

- Tjilbruke

- Warriparinga - site of the Living Kaurna Cultural Centre

Notes

- Tindale gives her date of death as 1931 (Tindale 1974, pp. 133,213)

- yerta means ("earth, ground, soil, country"), and was regarded by Taplin as equivalent to the word ruwe in Ngarrindjeri. The other Kaurna word pangkarra definitely implies land ownership (Amery 2016, p. 116)

- Milla mangkondi. Milla: a noun denoting violence or force. Mangkondi: a verb meaning to touch or grab hold of a woman, more specifically a young woman.

Citations

- Ross 1984, p. 5.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 65.

- Amery 2016, p. 3.

- Tindale 1974, p. 133.

- Clendon 2015, p. 2.

- Amery 2016, p. 57.

- Amery 2016, pp. 61,93.

- Amery 2016, pp. 64–65.

- Amery 2016, p. 65.

- Harris 2014.

- Amery 2016, pp. 66–68,86.

- Amery 2016, p. 86.

- Amery 2016, p. 4.

- Berndt, Berndt & Stanton 1993, p. 312.

- Wheatley 2009.

- Amery 2016, p. 5.

- Warburton 1981, p. xv.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 67.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 66.

- Amery 2016, p. 59.

- Jenkin 1979, p. 32.

- Tindale 1974.

- Amery 2016, p. 74.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 65,66.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 68.

- Lockwood 2017, pp. 68–69.

- Brown 1989, pp. 24–28.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 69.

- Lockwood 2017, pp. 70–71.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 71.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 73.

- Lockwood 2017, pp. 74–5.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 81.

- Lockwood 2017, p. 77.

- O'Brien & Paul 2013.

- Gara 2017, p. 86.

- Gara 2017, pp. 86–87.

- Gara 2017, pp. pp=86–87.

- Gara 2017, pp. 104–105.

- Gara 1990, p. 64.

- Amery 2016, p. 1.

- Whitmore.

- Ngadjuri Walpa Juri Lands and Heritage Association n.d.

- Parliament of South Australia 2006.

- Holdfast Bay 2003.

- NNTT 2000.

- "Native Title Determination Details: SCD2018/001 - Kaurna Peoples Native Title Claim". National Native Title Tribunal. 19 November 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2020. Kaurna People Native Title Settlement ILUA

- Richards, Stephanie (21 March 2018). ""Our ancestors will be smiling": Kaurna people gain native title rights". InDaily. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- "Kaurna Yerta is a step closer to finding a home in Tarntanya Adelaide". CityMag. 7 February 2020. Retrieved 16 May 2020.

- newsmaker.com.au 2009.

- ABC News 2009.

- Tindale 1974, p. 71.

- Tindale 1974, p. 73.

- Archived copy.

- Smith, Pate & Martin 2006.

- Ross 1984, pp. 3–5.

- Ross 1984, p. 3.

- Aboriginal and Historic Places around Metropolitan Adelaide and the South Coast Pg 8 (Tindale 1936)

- Aboriginal and Historic Places around Metropolitan Adelaide and the South Coast Pg 7

- Tindale 1974, p. 64.

- Tindale 1987, pp. 5–13.

- Amery 2016, p. 115.

- kaurnaculture.

- Amery & Buckskin 2009.

- Placenaming initiatives.

- Placename meanings.

- Kaurna place naming.

- Sutton 2019.

Sources

- "Aboriginal South Australians and Early Government of South Australia". Parliament of South Australia. 21 September 2006. Archived from the original on 20 July 2008. Retrieved 19 November 2008.

- "Adelaide City Council Placenaming Initiatives". Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- Amery, Rob (2016). Warraparna Kaurna!: Reclaiming an Australian language. University of Adelaide Press. ISBN 978-1-925-26125-7.

- Amery, Rob; Buckskin, Vincent (Jack) Kanya (March 2009). "Chapter 10. Pinning down Kaurna names: Linguistic issues arising in the development of the Kaurna Placenames Database" (PDF). In Hercus, Luise; Hodges, Flavia; Simpson, Jane (eds.). The Land is a Map: Placenames of Indigenous Origin in Australia. ANU Press. pp. 202–203. ISBN 978-1921536571.

- Berndt, Ronald Murray; Berndt, Catherine Helen; Stanton, John E. (1993). A World that was: The Yaraldi of the Murray River and the Lakes, South Australia. University of British Columbia UBC Press. ISBN 978-0-774-80478-3.

- Brown, Rosemary (March 1989). "The Brunskills of Sandford" (PDF). Newsletter of the Burnside Historical Societty. Vol. 9 no. 1. pp. 24–28.

- Clendon, Mark (2015). Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar: A commentary on the first section of a vocabulary of the Parnkalla language. University of Adelaide Press. ISBN 978-1-925-26111-0.

- Eacott, Alina (21 March 2018). "Kaurna people granted native title rights in Adelaide 18 years after claim". ABC News.

- Gara, Tom (December 1990). "The Life of Ivaritji ('Princess Amelia') of the Adelaide tribe" (PDF). Journal of the Anthropological Society of Adelaide. 28 (1): 64–105. ISSN 1034-4438.

- Gara, Tom (2017). "5. The Aboriginal Presence in Adelaide, 1860s–1960s". In Brock, Peggy; Gara, Tom (eds.). Colonialism and its Aftermath: A history of Aboriginal South Australia. Wakefield Press. pp. 86–105. ISBN 978-1743054994.

- Hamacher, Duane W. (2015). "Identifying Seasonal Stars in Kaurna Astronomical Traditions". Journal of Astronomical History and Heritage. 18 (1): 1–23. arXiv:1504.01570. Bibcode:2015JAHH...18...39H.

- Harris, Rhondda (6 February 2014). "Pirltawadli". SA History Hub (1 June 2017 (updated spelling) ed.). History Trust of South Australia. Retrieved 7 December 2019. Revised version of an entry first published in The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History 2001

- Hercus, Luise; Hodges, Flavia; Simpson, Jane, eds. (2009). The Land is a Map: Placenames of Indigenous Origin in Australia. ANU Press. ISBN 978-1921536571.

- Jenkin, Graham (1979). Conquest of the Ngarrindjeri. Rigby. ISBN 978-0-727-01112-1.

- "Kaurna Declare Sovereignty and $47.5 Million Dollar Bill for Marble Hill at SA Governor's Open House Day". newsmaker.com.au. 24 April 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- "Kaurna Peoples Native Title Claim". National Native Title Tribunal. 25 October 2000. Archived from the original on 15 October 2009. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- "Kaurna place naming: Recognising Kaurna heritage through physical features of the city". City of Adelaide. Retrieved 29 November 2019.

- "Kaurna Placename Meanings within the City of Adelaide". Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi. University of Adelaide. Retrieved 28 November 2019.

- "Kaurna Warra". kaurna.tripod.com. Archived from the original on 19 July 2011. Retrieved 19 July 2011.

- Lockwood, Christine (2017). "4. Early encounters on the Adelaide Plains and Encounter Bay". In Brock, Peggy; Gara, Tom (eds.). Colonialism and its Aftermath: A history of Aboriginal South Australia. Wakefield Press. pp. 65–81. ISBN 978-1743054994.

- Millar, Glen (12 August 2003). Native Title Claim - Update (PDF) (Report). City of Holdfast Bay. Archived from the original (PDF) on 14 March 2011. Retrieved 30 December 2009.

- Ngadjuri Walpa Juri Lands and Heritage Association (n.d.). Gnadjuri. SASOSE Council. ISBN 0-646-42821-7.

- O'Brien, Lewis Yerloburka; Paul, Mandy (8 December 2013). "Kaurna People". Government of South Australia. Retrieved 8 September 2017.

- Prest, Wilfred; Round, Kerrie; Fort, Carol, eds. (15 July 2001). The Wakefield Companion to South Australian History. Wakefield Press. ISBN 978-1862545595.

- Ross, Betty, ed. (1984). Aboriginal and Historic Places around Metropolitan Adelaide and the South Coast (PDF). Anthropological Society of South Australia. ISBN 0-9594806-2-5.

- "SA Govt rejects Marble Hill claim". ABC News. 1 July 2009. Retrieved 19 December 2017.

- Smith, Pam; Pate, F. Donald; Martin, Robert, eds. (2006). Valleys of Stone: The Archaeology and History of Adelaide's Hills Face (PDF). Belair: Kōpi Books. ISBN 978-0-727-01112-1.

- Sutton, Malcolm (1 August 2019). "Ancestral remains of the Kaurna people returned to country from UK in emotional Adelaide ceremony". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 1 August 2019.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (1974). "Kaurna (SA)". Aboriginal Tribes of Australia: Their Terrain, Environmental Controls, Distribution, Limits, and Proper Names. Australian National University Press. ISBN 978-0-708-10741-6.

- Tindale, Norman Barnett (May 1987). "The wanderings of Tjirbruki: a tale of the Kaurna people of Adelaide". Records of the South Australian Museum. 20: 5–13.

- "Tjilbruke Dreaming Tracks". kaurnaculture. Retrieved 26 February 2020.

- "'TJIRBUKI' or 'TJIRBUK' (Blowhole Beach)" (PDF). Kaurna Warrapintyandi The Southern Kaurna Place Names Project. 2016.

- Warburton, Elizabeth (1981). The paddocks beneath: a history of Burnside from the beginning. City of Burnside. ISBN 0959387609.

- Wheatley, Kim (20 November 2009). "Tribal War on Native Title". The Advertiser.

- "Whitmore Square". SA History Hub. History Trust of South Australia.

Further reading

- "Aboriginal people of South Australia: Kaurna". State Library of South Australia. – Guide to online resources

- Curnow, Paul (11 October 2011). "Kaurna Night Skies (Part I)". Australian Indigenous Astronomy.

- Curnow, Paul (20 October 2011). "Kaurna Night Skies (Part II)". Australian Indigenous Astronomy.

- "Home page: the Internet home of Kaurna Warra". Kaurna Warra Pintyanthi.

- "Kaurna". Mobile Language Team. University of Adelaide.

- "Kaurna calendar - Indigenous Weather Knowledge". Bureau of Meteorology.