Forstercooperia

Forstercooperia is an extinct genus of forstercooperiine paraceratheriid rhinoceros from the Middle Eocene of Asia.

| Forstercooperia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Restoration | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Perissodactyla |

| Family: | †Hyracodontidae |

| Subfamily: | †Indricotheriinae |

| Genus: | †Forstercooperia Wood, 1939 |

| Type species | |

| Cooperia totadentata Wood, 1938 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Species synonymy

| |

Description

Forstercooperia is known from a vast amount of cranial material, although only some scant postcranial remains.[1] The average size of the genus is about equal with a large dog, even though later genera like Juxia and Paraceratherium reached sizes of a cow and even much larger.[2] Like primitive rhinocerotoids, Forstercooperia possesses blunt ends on the tips of its nasals, above the nasal incision. Unlike all modern rhinoceroses, the nasals of Forstercooperia, as well as many related genera, lack rugosities, which suggests that they lacked any form of horn. The nasal incision extends fairly far into the upper jaw, ending just posterior to the canine. Forstercooperia possesses a small post-insicor diastema, not as large as its descendants, and similar in size to that of Hyracodon.[3]

Taxonomy

Forstercooperia is considered to be a primitive rhinocerotoid, and as a result, many unrelated species were lumped into it. Species have also been oversplit based on small or insignificant features. In the most inclusive review of the genus yet, it was identified that many of the species are junior synonyms of previous names, not in the genus, or are potentially invalid in some other way. Many specimens, ranging in age from the Middle Eocene to Late Eocene, and in location from eastern Asia to Kazakhstan, and as far west as United States, have at some time been included in Forstercooperia. Material of many different genera as well have been at some time included in Forstercooperia, such as that of Juxia[1] and Uintaceras[4]

In 1923, a mostly complete skull of an early rhinoceros relative was unearthed. This skull came from the Late Eocene of the Mongolian Irdin Manha Formation. The material, including the "front of skull with all premolars and some front teeth", was given the specimen number AMNH 20116. It was first discovered in the formation by George Olsen, and in 1938 it was described as a new genus and species by Horace Elmer Wood II. Wood named the binomial Cooperia totadentata to contain the skull. The generic name was to honor Clive Forster-Cooper, who had major contributions to the knowledge of indricotheres.[3] In 1939 Wood corrected the genus name to Forstercooperia, because he was informed that the name Cooperia was preoccupied, creating the new combination Fostercooperia totadentata.[5][1][6][7] The species is also the first named that has been included in Forstercooperia that is still valid.[4] It is also the senior synonym of F. shiwopuensis, a species named in 1974 by Chow et al..[1][8]

In 1963, material including a partial skull containing cheek teeth was unearthed in Late Eocene deposits of Mongolia. These remains were identified as from a true rhinoceros by Wood, who found them an important discovery with the scant amount of previous cranial material of early rhinocerotids available. On July 25, the same year, a paper was published by Wood concerning the taxonomy and osteology of these remains, in which he named them a new genus and species (or binomial) as well as re-ranking a previously named family as a subfamily containing the new taxon. The binomial created was Pappaceras confluens, classified as a close relative of Forstercooperia within Forstercooperiinae (before Forstercooperiidae, named in 1940 by Kretzoi). Wood noted that the generic name is derived from the Latin word πaππos, "grandfather", and the Greek words alpha, "without", and keras, "horn", translating as "Grandfather without horn". The species name is based on the confluent morphology of the teeth. The catalogue number for the skull is AMNH 26660, and it specifically preserved a "front half of the skull and a complete lower jaw, with most of the teeth and remaining alveoli, totaling a full placental series". Other remains included a portion of the mandible and a premolar. All of these specimens were from the lame locality, the Upper Gray Clays, of the Irdin Manha Formation in Inner Mongolia.[6] In the revision by Radnisky, it was found that this species was assignable to Forstercooperia, and the new combination F. confluens was erected.[9]

In the 1960s, newly uncovered material from the Irdin Manha Formation was identified as belonging to a new species of rhinocerotoid. Originally, they were found to be from F. confluens, as they were in the same location as that species holotype. They were later assigned to Forstercooperia sp., with no new name being given. The material included an almost complete skull, an almost complete lower jaw, an anterior portion of the skull, and an astragalus. These bones were first assigned a new species by Lucas et al., Forstercooperia minuta. They were found to be a unique species based on their size and the anatomy of their teeth. The species has been retained in the species complex of Forstercooperia throughout major revisions, by Lucas et al. in 1981,[1] Lucas and Sobus in 1989,[8] and Holbrook and Lucas in 1997. However, Holbrook and Lucas identified that the only North American material of F. minuta, F:AM 99662, had no features justifying its inclusion with the species, and reassigned it to their new binomial, Uintaceras radinskyi.[4]

An upper tooth row of an indricothere from the Eocene was first described in 1974. It was analysed by Chow, Chang and Ding, who published a new species for it, Forstercooperia shiwopuensis. The authors noted that it was from the same region and in the same size range as F. totadentata, which Lucas et al. (1981) found it to tentatively represent. The holotype of F. totadentata lacked an upper tooth row, and as it was presumably the right size to represent the missing teeth, Lucas et al. predicted it was of the same size and morphology as would have been predicted for the species.[1]

Species and synonyms

Forstercooperia has been represented by many different species in the different reviews of the genus.[1][4][8][9] In the first significant review, authored by Leonard Radinsky and published in 1967, found that many previous species were junior synonyms, and that only four species certainly in the genus were valid. Radinsky noted that of all published species, F. totadentata, F.? grandis, F. confluens, F. sharamurense, and F. borissiaki were the only valid ones, creating new combinations from Juxia sharamurense, Hyrachyus grandis, and Pappaceras borissiaki. He also synonymized the genera Pappaceras and Juxia with Forstercooperia.[9]

In a more recent review focused purely on the genus Forstercooperia, it was found that there was very little diversity in the species found valid by Radinsky. This paper, authored by Spencer G. Lucas and Robert Schoch and Earl Manning and published in 1981 reviewed all currently-named species of Forstercooperia, and named the new species F. minuta. Unlike Radinsky, their paper found Juxia to be separate, with F. borissiaki inside the genus, and F. grandis to be a definite species. F. confluens, named in 1963 by Wood, was found to be a synonym of F. grandis; F. sharamurunense, named in 1964 by Chow and Chiu, was found to be a synonym of F. borisiaki; F. jigniensis, named in 1973 by Sahni and Khare, was found to be an indeterminate species; F. shiwopuensis, named in 1974 by Chow, Chang and Ding, was found to be a synonym of F. totadentata; F. ergiliinensis, named in 1974 by Gabunia and Dashzeveg, was found to be a synonym of Juxia borissiaki; and F. crudus, named in 1977 by Gabunia, was found to be a nomen nudum.[1] In 1989, Lucas and Jay Sobus, it was noted that no new material of the genus had been identified, and that therefore, the conclusions were not changed.[8]

In the most recent review of the genus, focusing on the North American material, it was found that some earlier conclusions were no longer valid. This paper, published in 1997 by Luke Holbrook and Lucas, named a new genus, Uintaceras for all the North American material of Forstercooperia. Holbrook and Lucas named a new species, U. radinskyi, assigning the North American material of Fostercooperia to it. They found that the features uniting F. grandis with Forstercooperia were plesiomorphic, and that F. grandis was actually not a hyracodontid, instead the closest non-rhinocerotid relative of Rhinocerotidae. They concluded that F. grandis was a nomen dubium, its Asian material was assignable to F. confluens, Indricotheriinae was therefore only a Eurasian subfamily, and F. confluens was a valid species.[4] More recent mentions of Forstercooperia found no reason to contradict these conclusions.[10]

In 2016 new fostercooperiine material was reported from the early Eocene Arshanto Formation of Inner Mongolia, China. Wang and colleagues revalidated Pappaceras based on the new material and assigned it to a new species, P. meiomenus.[11]

Evolution

The superfamily Rhinocerotoidea can be traced back to the early Eocene—about 50 million years ago—with early precursors such as Hyrachyus. Rhinocerotoidea contains three families; the Amynodontidae, the Rhinocerotidae ("true rhinoceroses"), and the Hyracodontidae. The diversity within the rhinoceros group was much larger in prehistoric times; sizes ranged from dog-sized to the size of Paraceratherium. There were long-legged, cursorial forms and squat, semi aquatic forms. Most species did not have horns. Rhinoceros fossils are identified as such mainly by characteristics of their teeth, which is the part of the animals most likely to be preserved. The upper molars of most rhinoceroses have a pi (π) shaped pattern on the crown, and each lower molar has paired L-shapes. Various skull features are also used for identification of fossil rhinoceroses.[2]

The subfamily Forstercooperiinae, to which Forstercooperia belongs, is considered part of Paraceratheriidae, a group containing the largest land mammals ever to walk the earth.[11] Paraceratheres are distinguished by their larger size and the derived structure of their snouts, incisors and canines. The earliest known indricothere is the dog-sized Pappaceras. The cow-sized Juxia is known from the middle Eocene; by the late Eocene the genus Urtinotherium of Asia had almost reached the size of the largest genus Paraceratherium.[2][8][2][4][8] The genus is distinct because of features of its nasal incision, dentition, tooth anatomy, and tooth proportions and size.[1] It retained the relatively primitive features of possessing three incisors, lower canines, and lower first premolars.[2]

Below is a phylogenetic analysis conducted by Lucas and Sobus in their 1989 revision of Indricotheriinae:[8]

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||

In a 1999 study, Holbrook instead found the paraceratheres to be outside the hyracodontid group and wrote that the paraceratheres may not be a monophyletic grouping. He performed a phylogenetic analysis which placed Uintaceras, then amynodontids, then Paraceratherium, then Juxia and Forstercooperia, and finally hyracodontids as the successive outgroups of Rhinocerotidae within Rhinocerotoidea. The analysis however, did not include the genus Urtinotherium.[12] Later cladistic analysis confirmed some conclusions of Holbrook (1999), recovering hyracodontids as the basalmost rhinocerotoids and paraceratheres as closely related to Eggysodontidae and crown rhinos.[11]

Distribution and habitat

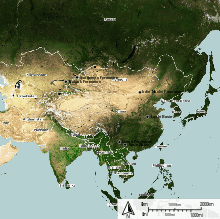

Remains of Forstercooperia have been found all across Asia. Most important remains are from the Middle to Late Eocene Irdin Manha Formation of Inner Mongolia (China).[1] In 1938, the holotype of F. totadentata was described, from the Irdin Manha Formation.[3] The only non-holotypic specimen of F. totadentata is that of F. shiwopuensis, which comes from the Lunan Formation of China.[1]

References

- Lucas, S.G.; Schoch, R.M.; Manning, E. (1981). "The Systematics of Forstercooperia, a Middle to Late Eocene Hyracodontid (Perissodactyla: Rhinocerotoidea) from Asia and Western North America". Journal of Paleontology. 55 (4): 826–841. JSTOR 1304430.

- Prothero, D.R. (2013). Rhinoceros Giants: The Palaeobiology of Indricotheres. Indiana University Press. pp. 1–160. ISBN 978-0-253-00819-0.

- Wood, H.E. (1938). "Cooperia totadentata, a remarkable rhinoceros from the Eocene of Mongolia" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 1012: 1–20.

- Holbrook, L.T.; Lucas, S.G. (1997). "A New Genus of Rhinocerotoid from the Eocene of Utah and the Status of North American "Forstercooperia"". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (2): 384–396. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010983. JSTOR 4523815.

- Wood, H.E. (1939). "Addendum to American Museum Novitates No. 1012" (PDF). American Museum Novitates. 1012: 1.

- Wood, H.E. (1963). "A Primitive Rhinoceros from the Late Eocene of Mongolia". American Museum Novitates (2146): 1–12.

- Lucas, S.G.; Emry, R.J.; Bayshashanov, B.U. (1997). "Eocene Perissodactyla from the Shinzhaly River, Eastern Kazakhstan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 17 (1): 235–246. doi:10.1080/02724634.1997.10010967. JSTOR 4523800.

- Lucas, S.G.; Sobus, J.C. (1989). "The Systematics of Indricotheres". In Prothero, Donald R.; Schoch, Robert M. (eds.). The Evolution of Perissodactyls. Oxford University Press. pp. 358–378. ISBN 978-0-19-506039-3. OCLC 19268080.

- Radinsky, L.B. (1967). "A Review of the Rhinocerotoid Family Hyracodontidae (Perissodactyla)". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 136 (1): 1–46.

- Prothero, D.R. (2005). The Evolution of North American Rhinoceroses. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–218. ISBN 0-521-83240-3.

- Haibing Wang; Bin Bai; Jin Meng; Yuanqing Wang (2016). "Earliest known unequivocal rhinocerotoid sheds new light on the origin of Giant Rhinos and phylogeny of early rhinocerotoids". Scientific Reports. 6: Article number 39607. doi:10.1038/srep39607.

- Holbrook, L.T. (1999). "The Phylogeny and Classification of Tapiromorph Perissodactyls (Mammalia)". Cladistics. 15 (3): 331–350. doi:10.1006/clad.1999.0107.