Finedon

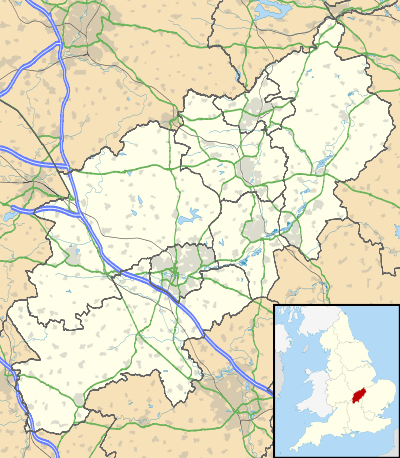

Finedon is a small town in the Borough of Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, with a population at the 2011 census of 4,309 people.[1] In 1086 when the Domesday Book was completed, Finedon (then known as Tingdene) was a large royal manor, previously held by Queen Edith, wife of Edward the Confessor. From the 1860s the parish was much excavated for its iron ore, which lay underneath a layer of limestone and was quarried over the course of 100 years or more. Local furnaces produced pig iron and later the quarries supplied ore for the steel works at Corby. A disused quarry face in the south of the parish is a geological SSSI.

| Finedon | |

|---|---|

Finedon Water Tower, now a house | |

Finedon Location within Northamptonshire | |

| Population | 4,309 (2011 census) |

| OS grid reference | SP9171 |

| District |

|

| Shire county | |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | Wellingborough |

| Postcode district | NN9 |

| Dialling code | 01933 |

| Police | Northamptonshire |

| Fire | Northamptonshire |

| Ambulance | East Midlands |

| UK Parliament | |

|

Finedon is situated 4 miles (6.4 km) to the north east of Wellingborough.[2] Nearby communities include Irthlingborough, Burton Latimer and Great Harrowden.

History

Domesday Book

In 1086 when the Domesday Book was completed, Finedon was a large royal manor, previously held by Queen Edith. At this time the village (now a town) was known as Tingdene, which originates from the Old English words þing meaning assembly or meeting and Denu meaning valley or vale.[3] Tingdene and the later version, Thingdon, were used until the early nineteenth century until finally Finedon became the commonly accepted version, both in written format as well as in pronunciation.[4]

At the time of the Domesday Book Finedon was one of only four towns listed with a population greater than 50 in Northamptonshire - the others being Northampton, Brackley and Rushton.

The Bell Inn also claims to be listed in the Domesday Book, but the current building does not date back to this period, and there is evidence that the original inn was situated several hundred metres away. However, the main building was built around 1598, with the current façade added in 1872.

St Mary's Church

The Parish Church of St Mary the Virgin, is a mid-14th-century church with an aisled nave of four bays. The current parish priest is Rev Richard Coles, a broadcaster and former member of pop group The Communards.

The tower houses a ring of eight bells in the key of D, with the tenor weighing just over 21 hundredweight (about 1.1 tonnes).[5] The church also houses an organ which was probably originally built for St George's Chapel in Windsor Castle in 1704.[6] It was installed in 1717, rebuilt in 1872, and restored in 1960,[7] and it retains its tracker action.

Finedon Hall

Finedon Hall is a Grade II listed 17th- or 18th-century country house with later modifications. It is built in the Tudor style to an H-shaped floor plan in two storeys with attics. It is constructed in ironstone ashlar with limestone dressings and a slate roof.[8]

The house has now been converted into apartments.

Finedon Obelisk

The Finedon Obelisk is a monument erected in 1789 to record the blessings of the year by Sir John English Dolben, the fourth and last of the Dolben baronets and lord of the manor of Finedon. The blessings are thought to include the return to sanity of George III. The 23 April 1789 was appointed a day of thanksgiving to commemorate the event, which in Finedon was celebrated with bell ringing, fireworks and the firing of cannon.

The obelisk is located in a small enclosure next to the A6 and A510 roundabout.

Volta Tower

Finedon was formerly home to the Volta Tower, a folly built in 1865 by William Harcourt Isham Mackworth-Dolben of Finedon Hall. It was built to commemorate the death of his eldest son, Lieutenant Commander William Digby Dolben, who drowned off the west coast of Africa on 1 September 1863, aged 24. The building stood for 86 years before collapsing in 1951, killing one of its residents.

Water Tower

The Water Tower was completed in 1904, originally costing £1500 to build, with the whole scheme of public water provision for Finedon costing £13,000. The tower is octagonal in shape and is divided into five interior stages. The exterior of the building is a red, yellow and blue polychrome brick design with a lead and plain-tile roof.

The Water Tower has since been converted into a private residence and in 1973, gained Grade II listed status.[9] It stands as a local landmark beside the A6 on the southern entrance into Finedon.

Governance

At the introduction of modern Local Government by the Local Government Act 1894, Finedon was designated an Urban District, with an Urban District Council. In 1935 the Finedon Urban District was abolished, and Finedon became part of the Wellingborough Urban District. In 1983, Finedon Parish Council was established, to provide better local representation and influence in decision-making. it currently has thirteen members.[10]

The town is within the Borough of Wellingborough and the Wellingborough Parliamentary constituency.

Education

Finedon is served by two primary schools, the Finedon Infant School for children aged 4 to 7, and the Finedon Mulso Church of England Junior school for ages 7 to 11. The two schools became federated in 2011 and are now operated as one school with one headteacher. Supervisory childcare is available both before and after conventional school hours by the Apple Tree Club, located next to the Infant School.[11]

There is no secondary school in Finedon, so pupils are required to travel outside of the town to continue their education after leaving the Junior school. Huxlow Science College in Irthlingborough accommodates the large majority of these pupils, with the provision of a free bus pass. It is not uncommon however for some to attend Latimer Arts College in Barton Seagrave or Bishop Stopford School in Kettering.

Pre-school and early years' education for ages 2 and up is catered for by St Michael's playgroup, rated "Good" by Ofsted in July 2014.[12]

Banks Park

Finedon's main park, complete with outdoor tennis courts and an open place popular among dog walkers and cyclists. There is also a play area for children consisting of Swings, climbing frame, roundabout, assault course and more. Banks Park sits between Burton Road, High Street and Wellingborough Road, Finedon and can be accessed from both High Street and Wellingborough Road.

Pocket Park

From 1939 until 1946 ironstone was extracted from the quarry at Finedon and transported via a railway line to the main line at Wellingborough.

Rather than filling in the railway cutting and quarry and returning it to agricultural land, the people of Finedon campaigned to retain it as an important wildlife area. In 1984, it was designated the first Pocket Park in the country.[13] The heritage of the park as a quarry led to it earning its local name "The Pits".

The quarry area is predominantly grassland and scrub with ponds supporting a diverse range of amphibians. The majority of the railway cutting is woodland containing mainly ash, sycamore and oak. The park is owned by the Borough Council of Wellingborough and is managed by a team of volunteers from the Finedon branch of the Northamptonshire Wildlife Trust to maximise its benefit for the flora and fauna. Scrub in the quarry is cut back to maintain the grassland, whilst large trees and other patches of scrub are left to provide feeding and nesting sites for birds. The ponds are also managed to ensure they do not become completely overhung by trees.

Old coppiced lime trees estimated to be over three hundred years as well as yews of considerable age are to be found alongside the labyrinth of trails that cross the site.

Access to the park can be found via Station Road and Avenue Road, next to the Finedon Dolben Cricket Club.

To the south western side of Finedon Pocket Park is another nature reserve, Finedon Cally Banks,[14] owned and managed by the Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire. The name Cally Banks comes from the process of burning iron ore to remove impurities, leaving a deposit called calcine which provides the poor soil conditions in which wildflowers flourish.

Finedon ironstone

The dark brown ironstone that underlies the parish is one of Northamptonshire's more durable building stones, unlike much of the ironstone elsewhere in the county which can become crumbly or delaminate.[15] The 14th-century church is built mainly from this stone, which is presumed to have been quarried locally (with paler coloured limestone of Weldon Stone around the windows and door.) Other older buildings in the town also use the local ironstone, notably the vicarage and a house opposite the church built in 1712 as a charity school for girls.[15] The various works of the Dolben family also make use of the ironstone. Chemical changes within the stone, while it was still in the ground, have resulted in a hard crystalline mineral version of Limonite which bonds the particles together, creating a harder, more durable ironstone, but which was still workable when lifted from the ground. An Enclosure map of 1805 records two stone pits in the town.[15]

Quarries

In the early part of Britain's industrial revolution the Northamptonshire ironstone was ignored as a source of iron ore because unlike areas such as South Wales and the north of England, it had no coal to power the furnaces. In the mid 19th century the railways arrived, which meant that either the ore could be taken to distant furnaces, or coal brought to furnaces near the iron deposits.[16] Both happened at Finedon from the 1860s.

Glendon Iron Ore Company

Quarries in the Finedon and Burton Latimer area, began with the workings of the Glendon Iron Ore Company, who in 1866 built the Finedon Furnaces, near Finedon station, along the eastern side the Midland Railway that had opened in 1857. Furnace Lane still runs through the industrial estate where the furnace once stood. The open-top furnace produced pig iron from 1866 to 1891,[17] and numerous quarry pits to the north, east and south of the town were engaged in the laborious task of clearing back overlying rocks (sometimes up to 25 feet thick) using wheelbarrows and planks. The underlying ironstone was then loaded into wagons which used a series of tramways to get the ore to the furnace, or later processed at a Calciting plant and then transported by rail to furnaces in the coal fields of Derbyshire or beyond.[18]

Stanton Ironworks

Areas south and east of the town were quarried by the Stanton Ironworks Company, who began using Northamptonshire ironstone in 1865. By 1869 they were leasing quarries on the Finedon Hall estate and built a narrow-gauge tramway to connect to the Midland Railway,[19] and from there the ore was transported by rail to their furnaces at Stanton by Dale, Derbyshire.[20]

Neilson's Quarries

Walter Neilson was quarrying in areas close to the town, either side of Ryegate Hill from before 1879.[21] In 1881 he laid Neilson's Tramway a 2 ft 4 in (711 mm) gauge tramway down to sidings on the Midland Railway. These siding were called "Neilson's Sidings" until at least the 1990s.[22] Neilson's original pits were exhausted by 1892 and he leased new land on the east side of Finedon Road, immediately south of the town. This new pit was known as Thingdon Quarry. In 1911 Neilson's operation was taken over by Wellingborough Iron Company (see below).[23]

Wellingborough Iron Company

To the south and east of the town, several companies operated quarries. Amongst these were the Rixon Iron and Brick company, which began quarrying near Finedon in 1874. Rixon laid the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge Wellingborough Tramway to connect their ironstone pits to sidings of the Midland Railway. Rixon built their own ironworks alongside the Midland Railway in 1884. In 1887, Rixon's company declared bankruptcy and was taken over by the newly-formed Wellingborough Iron Company. They relaid the tramway and opened up several more ironstone pits south of Finedon. In 1911, Stanton took over Neilson's Thingdon Quarry immediately south of the town and started a series underground mines there in 1913. In 1932, the whole operation was merged with the Stanton Ironworks company.[23]

Stanton Ironworks Company was acquired by Stewarts & Lloyds in 1939,[23] which was one of the companies that were merged and nationalised to become British Steel in 1967.[24]

Ironstone production

Quarried ironstone from the area had initially produced pig iron for use in cast-iron production. After 1879, with the development of the Gilchrist-Thomas converter the production of steel was made possible using iron ore with a high Phosphate content, such as the Northamptonshire Ironstone.[16] Around Finedon the quarries south of the town near Ryebury Hill and Sidegate Lane had been worked extensively between the 1870s and 1900s, using a labour-intensive method in which a long trench (or gullet) through the overburden was established, along which a tramway could transport the ore. The overburden (often of considerable depth) was loaded into wheelbarrows and taken via planks suspended over the trench, to be dumped on the far side, so that the next section of ore could be dug out.[18] In this way the trench would gradually migrate across a field, and the reinstated land would be several feet lower than the surrounding fields. In the 20th century the introduction of ever larger dragline excavators allowed faster working with far fewer people employed.[16] The smaller steel plants had all been merged in 1967 and most were shut down in favour of the Corby Works. This too ceased steel production in 1980, and all Finedon quarrying had ceased by that point.[16]

Geological SSSI

Towards the southern end of the parish, one of the quarries that had been worked since at least the 1920s is Finedon Top Lodge Quarry. By the mid-1960 it was being worked by Stewarts & Lloyds Ltd (to whom it was known as Wellingborough No. 5 pit), who transported the ironstone to the steel works at Corby.[25] In 1986 it was declared a Site of Special Scientific Interest on account of its geological significance.[26] Although the quarry is no longer in use, the surviving rock-face has been given legal protection for its value in showing a representative section through the Middle Jurassic sedimentary beds. At its base, although no longer visible, is the ironstone which is part of the 'Northampton Sand Formation' of rocks. Everything above the ironstone would have been just 'overburden' to the quarrymen, which needed to be excavated and moved to the other side of the gullet, to allow the ironstone to be accessed. However they are now a piece of the evidence in building up an understanding of how the geology of Northamptonshire during the Jurassic period came into being. Almost all the layers of rock in the overburden were laid down during the Bathonian Stage of the Middle Jurassic. The layers accumulated over some 2 million years, beginning 168 million years ago, several million years after the ironstone had stopped being deposited. The cliff face reveals a 4 metres (13 ft) layer of limestone and other material known as the 'Wellingborough Member' for which this quarry face is the type section.[27] Above that is a further 6 metres (20 ft) of harder limestone beds known as the 'Blisworth Limestone Formation'.[27]

Climate

Finedon, much like the rest of the British Isles, experiences an oceanic climate and as such does not endure extreme temperatures and benefits from fairly evenly spread rainfall throughout the year.

| Climate data for Finedon, GBR | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Average high °C (°F) | 7 (45) |

8 (46) |

10 (50) |

13 (55) |

16 (61) |

19 (66) |

22 (72) |

22 (72) |

19 (66) |

14 (57) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

14 (57) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 2 (36) |

2 (36) |

3 (37) |

4 (39) |

7 (45) |

10 (50) |

12 (54) |

12 (54) |

10 (50) |

7 (45) |

4 (39) |

2 (36) |

6 (43) |

| Average precipitation cm (inches) | 4.3 (1.7) |

3.4 (1.3) |

3.1 (1.2) |

3.9 (1.5) |

4.0 (1.6) |

4.8 (1.9) |

5.0 (2.0) |

5.0 (2.0) |

5.1 (2.0) |

6.2 (2.4) |

4.8 (1.9) |

4.7 (1.9) |

54.3 (21.4) |

| Source: [28] | |||||||||||||

Notable people

- Arthur Henfrey, football player for England between 1891 and 1896

- Sir William Dolben, 3rd Baronet, MP and campaigner for the abolition of slavery

- Digby Mackworth Dolben, poet brought up at Finedon Hall

- Richard Coles, Vicar of Finedon parish since 2011[29] and former pop musician with The Communards

Town Twinning

Along with Wellingborough, Finedon is twinned with:[30]

References

Notes

- Office for National Statistics: Finedon CP: Parish headcounts. Retrieved 15 July 2015

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Parish information on Finedon and Great Doddington Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- English Place Name Society Retrieved 22 March 2012

- John Bailey, Finedon Otherwise Thingdon, 1975, ISBN 0-9504250-0-1

- Finedon Bellringers

- National Pipe Organ Register, N03520

- National Pipe Organ Register, N03521

- "Finedon Hall, Finedon". British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 13 April 2013.

- British Listed Buildings. Retrieved 15 July 2015.

- "Welcome to Finedon Parish Council". Finedone Parish Council. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Finedon Schools Website Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Ofsted Inspection Reports: St Michael's Playgroup Retrieved 16 July 2015.

- Northamptonshire County Council, Pocket Parks Retrieved 5 July 2017

- Wildlife Trust for Bedfordshire, Cambridgeshire and Northamptonshire Retrieved 15 July 2015

- Sutherland, D.S. (2003). Northamptonshire Stone. Dovecote Press. pp. 43–45. ISBN 190434917X.

- The Living Ironstone Museum, Cottesmore. "A Brief History of Iron Ore Mining in the East Midlands". Rocks by Rail. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Signalling Record Society. "RailRef Line Codes - Industrial & Private: Northamptonshire". Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Greg Evans (2005). "The History of Ironstone Mining around Burton Latimer". Burton Latimer Heritage Society. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Turnock, David (1998). An Historical Geography of Railways in Great Britain and Ireland. Ashgate. p. 289. ISBN 1351958933.

- "Stanton Iron Works Co". Grace's Guide to British Industrial History. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

- Dawson, Michael (2012). "Figure 10: The proposed site in 1890-1905". Heritage Assessment: Land at Sidegate Lane, Wellingborough, Northamtonshire (PDF) (Report). CgMs Consulting. p. 18.

- Tonks, Eric (May 1990). The Ironstone Quarries of the Midlands Part 4: The Wellingborough Area. Cheltenham: Runpast Publishing. ISBN 1-870-754-042.

- Quine, Dan (2016). Four East Midlands Ironstone Tramways Part Three: Wellingborough. 108. Garndolbenmaen: Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review.

- "Finedon (Wellingborough) Iron Quarry (United Kingdom)". aditnow.co.uk. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Torrens, H.S. (1968). "The Great Oolite Series". In P.C.Sylvester-Bradley & Trevor D. Ford (ed.). The Geology of the East Midlands. Leicester University Press. p. 259. ISBN 0718510720.

- "Finedon Top Lodge Quarry citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Wyatt, R.J. (2002). "Finedon Gullet, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire". In B.M Cox and M.G. Sumbler (ed.). British Middle Jurassic Stratigraphy. Geological Conservation Review Series No. 26. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. pp. 258–260. ISBN 1861074794.

- "Average weather for Finedon".

- Daily Telegraph report

- Borough Council of Wellingborough: Town Twinning Retrieved 20 July 2015.

Sources

- John Bailey (1987). Finedon Revealed. Finedon: J.L.H. Bailey. ISBN 0-9504250-1-X. OCLC 16078775.

- John Bailey (2004). Look at Finedon. Finedon: J.L.H. Bailey. ISBN 0-9504250-2-8. OCLC 62584735.

- Finedon Historical Society, Finedon Yards

- Audrey Ellis, Memories of Finedon http://www.audrey-ellis.co.uk

- Rosemary Pearson, The Top School

External links

![]()

- Church of St Mary the Virgin, Finedon Online Parish Magazine

- Finedon Web Site Finedon

- http://www.finedonlocalhistorysociety.co.uk/ Finedon local history Society Finedon History

- Finedon Bellringers Information about the Bellringers

- A Pictorial view of Finedon A selection of Photographs of Finedon