Finedon Top Lodge Quarry

Finedon Top Lodge Quarry, also known as Finedon Gullet (and in the 1960s documented as 'Wellingborough No. 5 Pit') is a 0.9 hectare geological Site of Special Scientific Interest east of Wellingborough in Northamptonshire.[1][2] It is a Geological Conservation Review site[3] revealing a sequence of middle Jurassic limestones, sandstones and ironstones, and is the type section for a sequence of sedimentary rocks known as the 'Wellingborough Member'. It was created by quarrying for the underlying ironstone for use at Wellingborough and Corby Steelworks; the ore was transported by the 1,000 mm (3 ft 3 3⁄8 in) gauge Wellingborough Tramway.[4]

| Site of Special Scientific Interest | |

| |

| Area of Search | Northamptonshire |

|---|---|

| Grid reference | SP 926 699[1] |

| Interest | Geological 168.1–166.1 Ma |

| Area | 0.9 hectares[1] |

| Notification | 1986[1] |

| Location map | Magic Map |

|

| Location of Finedon Top Lodge Quarry, a Northamptonshire SSSI. |

Geology

| Substages of the Aalenian to Bathonian Ages | Geological formations within the Great Oolite Group[6] | Rock units found at Finedon Gullet |

|---|---|---|

| Upper Bathonian (ends c.166.1 Ma) |

Blisworth Limestone Formation | Digonoides Beds, named after a brachiopod (lampshell) fossil Digonella digonoides: 2.1m limestone without fossils 2.0m shelly limestone |

| Middle Bathonian | Sharpi Beds: 2.0m of this regionally distinctive limestone, named after a brachiopod fossil, Sharpirhynchia sharpi, which in turn is named after Samuel Sharp (geologist) (1814–1882).[7] | |

| Rutland Formation | Cranford Rhythm | |

| Lower Bathonian (begins 168.3 Ma) |

Wellingborough Limestone Member: A 4.6m series of mud and limestone beds for which Finedon Gullet serves as the 'Type section'. | |

| Stamford Member: 1.3m of muddy clays and sandy silts, including ironstone nodules.[8] | ||

| Upper and Lower Bajocian | Unconformity: a gap of several million years with no rocks represented. | |

| Aalenian (174.1 to 170.3 Ma)[9] | ||

| Northampton Sand Formation: (part of the Inferior Oolite Group) |

Northampton Ironstone (no longer visible at the quarry) | |

This quarry face revealed a complete section of the Rutland Formation dating to the Bathonian stage of the Middle Jurassic, 168 to 166 million years ago, although by 1997 only the top 4m of that formation was visible. It is the type section for the Wellingborough Member, and contains fossils of oysters and Rhynchonellida.[10]

Finedon Top Lodge

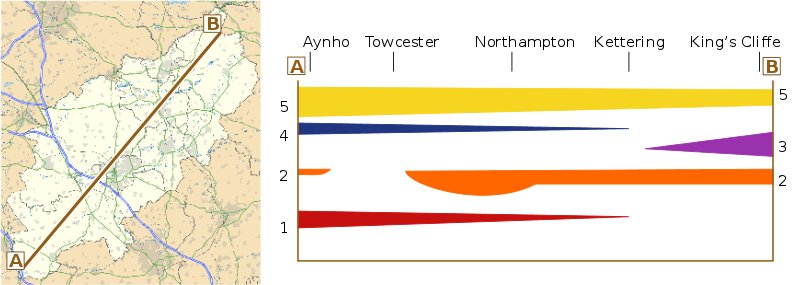

The very simplified diagram is not to scale, and has massive vertical exaggeration. It shows a vertical section through the strata from Aynho to King's Cliffe (line A to B on the map), and ignores the many river valleys and other topographical features. Various sedimentary rocks were laid down over the Middle Jurassic Epoch during periods of shallow seas and deeper oceans, in what is now Northamptonshire, creating the Oolitic limestones, sandstones and ironstones found across the length of the county. Various deposition periods were separated by periods above sea level, creating formations that get progressively thinner and then become absent in places that had periods without any deposition. The grey rectangle indicates how the Finedon Top Lodge Quarry face fits into this diagramatic scheme. Only the top half of the quarry face is now visible.

Key to the rocks shown:-

- 5. Blisworth Limestone Formation.

- 4. Wellingborough Limestone (part of the Rutland Formation of diverse layers of limestones, sand, silts and clays), which continues to the south-west and becomes known in Oxfordshire as the Taynton Limestone Formation.

- 3. Lincolnshire Limestone Formation (only occurs northward of Kettering).

- 2. Northampton Sand Formation (which includes some of the main ironstones).

- 1. Marlestone Rock Formation (continues south-west into Oxfordshire).[11]

Ironstone

The oldest rocks in the quarry sequence, and so the lowest strata of rocks, are the ironstone beds which are part of the Northampton Sand Formation, a layer of rocks that outcrops along the length of the county, and is the source of much of the deep brown ironstone that is characteristic of churches and cottages in many Northamptonshire villages. The stone was laid down in shallow seas during a Biozone known as the Scissum Zone, early in the Aalenian Age,[7] and lies within a wider rock group stretching from Dorset to Yorkshire, called the Inferior Oolite Group. ('Inferior' indicating it is below the Great Oolite Group). At Finedon Top Lodge the beds, which had not been used for building stone due to being too deep to access, were quarried by open cast mining for the iron content as the Northamptonshire iron and steel works grew up from the 1860s onwards.[11]

Wellingborough Limestone

The Stamford Member, Wellingborough Member and Cranford rhythm lie directly on the ironstone, despite a passage of 2 million years between their formation. The shallow seas that had covered the area during the Aalenian Age had receded by the following Bajocian Age, and in this part of Northamptonshire the dry land received (or retained) no new sediments. When the sea returned (due either to globally rising sea levels or locally descending land areas) during the Early Bathonian Age, during a Biozone known as the Zigzag Zone, new sedimentation took place. In the case of the Stamford Member, this was a freshwater lake on the coastal plain of an area of higher ground[5] dubbed the Anglo-Belgian Landmass.[11] The Biozone that follows 'Zigzag' is 'Tenuiplicatus', which has no sedimentation here, unlike areas further north as seen at Ketton and Clipsham. This was a much shorter period than the earlier unconformity, however, and with further deepening of the seas across what is now north-west Northamptonshire, the Finedon Quarry area became a brackish lagoon. This was sometimes deeper, resulting in fully marine limestone, sometimes with the deposition nearing the surface again allowing the growth of plants. The resulting rocks of the Wellingborough Member have rhythmic strata of Limestone often with great quantities of oyster shells, interspersed with rootlet beds as the land emerged or submerged. The Wellingborough Member is a thinner and more fragmented extension of a much thicker and more consistent limestone known as the Taynton Limestone Formation that formed at the same time in deeper seas over much of Oxfordshire and Gloucestershire.[5] The Wellingborough Member was formerly interpreted as being formed in an estuary, and was named 'Upper Estuarine Limestone' for most of the 20th century.[12]

Blisworth Limestone

Formerly known as the 'Great Oolite Limestone', the Blisworth Limestone is a widespread series of limestone beds that run the full length of Northamptonshire. They were laid down in a fully marine saltwater sea at the end of the Bathonian Age, at a time when the earlier lagoons were once more below sea level over a wide area, so that a wide area, including the largely flat surface of the earlier Cranford rhythm received a deposition that was at times mud and other outwash from the nearby landmass, and at other times accumulations of shells and other marine detritus[5] which also received substantial precipitation of limestone held within the seawater. The beds are named after a village with extensive quarries south of Northampton, where it was studied at the end of the 18th century whilst the Blisworth Tunnel was being built for the Grand Union Canal. The Limestone has been widely used across Northamptonshire for building stone, and takes a wide variety of colours in cream and beige - rather than the dark browns of the ironstones. In form, it is variable, but generally fine grained, and less often Ooidal.[11] The Finedon Gullet rockface shows two beds, the lower, known as the Sharpi beds, has large accumulations of shell and fossil elements, including oysters and other bivalves, and a brachiopod fossil, Sharpirhynchia sharpi, (formerly called Kallirhynchia sharpi) which in turn is named after Samuel Sharp, a 19th-century geologist who published his detailed accounts of local quarries in the 1870s.[11] This bed is placed in the Morrisi Biozone. Above the Sharpi beds, rock beds 4m of limestone is found, the lower half of which has fossils and shells, whilst the upper half is more massive blocks with fewer or no fossils. These layers appear to correlate to the Audley member of the White Limestone Formation further south in Oxfordshire. This would place it in the Retrocostatum Biozone and it is inferred to belong to what are known as the 'Diginoides Beds', although the diagnostic brachiopod fossil Digonella digonoides has not been found at this outcrop. This zoning suggests no deposits from the intervening Bremeri Biozone, implying either no sedimentation or a period of erosion between the Sharpi and Diginoides beds.[5]

Above the limestone is a layer of Blisworth Clay Formation, thought to be close in date to the topmost limestone. There is no further surviving deposits from the next 166 million years. Even the ice ages of the Quaternary Period appear not to have left any boulder clay here, unlike in much of the county.[13]

Quarrying

Finedon Gullet is a linear cliff feature that forms a south facing outcrop resulting from excavation of the ironstone and overlying rocks east of Finedon Top Lodge. Since active quarrying stopped its base has acquired a build up of material obscuring the lower beds, and a substantial linear pond lies along the length of the outcrop. The quarry was one of many around Finedon, where extensive ironstone quarrying began in the 1860s and continued for 100 years. By the mid-1960 Finedon Top Lodge Quarry was being worked by Stewarts & Lloyds Ltd (to whom it was known as Wellingborough No. 5 pit),[14] providing ore for their steel works at Corby. The narrow-gaugeWellingborough Tramway took the ore from this and numerous other nearby quarries to the furnace sites and railway sidings north-east of Wellingborough. A larger such quarry to the north of Top Lodge became the Sidegate Lane landfill site from the 1970s.[15]

The quarries worked by creating a long trench (or gullet) through the overburden, along the base of which a tramway could transport the ore. The overburden (often of considerable depth) was excavated and dumped on the far side of the gullet, so that the next section of ore could be dug out.[16] In this way the trench would gradually migrate across a field, and the reinstated land would be several feet lower than the surrounding fields. The early quarries had moved all the excavated rock by hand, loading it into wheelbarrows and pushing it via planks suspended over the trench, to be dropped on the far side. By the time this quarry was being opened up, probably in the 1920s[17] there were mechanical excavators, and the quarries used ever larger dragline excavators to maximise production with the fewest people employed.[18]. In 1940, Finedon Top Lodge Quarry was the first in Britain to use a walking dragline excavator.[4]

Access

There is no public access to the quarry face, which is on private land. A public footpath runs by the eastern end of the site.

References

- "Designated Sites View: Finedon Top Lodge Quarry". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Map of Finedon Top Lodge Quarry". Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- "Wellingborough (Bathonian)". Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Quine, Dan (2016). Four East Midlands Ironstone Tramways Part Three: Wellingborough. 108. Garndolbenmaen: Narrow Gauge and Industrial Railway Modelling Review.

- Wyatt, R.J. (2002). "Finedon Gullet, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire". In B.M Cox and M.G. Sumbler (ed.). British Middle Jurassic Stratigraphy. Geological Conservation Review Series No. 26. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. pp. 258–260. ISBN 1861074794.

- "Great Oolite Group". The BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- Cox, B.M.; Sumbler, M.G. (2002). British Middle Jurassic Stratigraphy. Geological Conservation Review Series No. 26. Peterborough: Joint Nature Conservation Committee. p. 229. ISBN 1861074794.

- "Stamford Member". The BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 22 June 2017.

- "International Commission on Stratigraphy: Chronostratographical Chart". stratigraphy.org. 2017.

- "Finedon Top Lodge Quarry citation" (PDF). Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Natural England. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 March 2017. Retrieved 27 March 2017.

- Sutherland, D.S. (2003). Northamptonshire Stone. Dovecote Press. p. 31. ISBN 190434917X.

- "Wellingborough Limestone Member". The BGS Lexicon of Named Rock Units. British Geological Survey. Retrieved 1 July 2017.

- Sutherland, 2003, p.17

- Torrens, H.S. (1968). "The Great Oolite Series". In P.C.Sylvester-Bradley & Trevor D. Ford (ed.). The Geology of the East Midlands. Leicester University Press. p. 259. ISBN 0718510720.

- GP Planning Ltd (2012). Sidegate Lane, Wellingborough: Application For A Resource Recovery Facility (PDF) (Report).

- Greg Evans (2005). "The History of Ironstone Mining around Burton Latimer". Burton Latimer Heritage Society. Retrieved 10 July 2017.

- Dawson, Michael (2012). "Appendix 2: map of 1927". Heritage Assessment: Land at Sidegate Lane, Wellingborough, Northamptonshire (PDF) (Report). CgMs Consulting. p. 25.

- The Living Ironstone Museum, Cottesmore. "A Brief History of Iron Ore Mining in the East Midlands". Rocks by Rail. Retrieved 9 July 2017.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Finedon Top Lodge Quarry. |