Farringdon Without

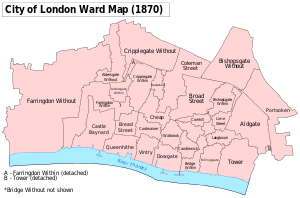

Farringdon Without is the most westerly Ward of the City of London, its suffix Without reflects its origin as lying beyond the City’s former defensive walls. It was first established in 1394 to administer the suburbs west of Ludgate and Newgate, and also around West Smithfield. This was achieved by splitting the very large, pre-existing Farringdon Ward into two parts, Farringdon Within and Farringdon Without.

| Ward of Farringdon Without | |

|---|---|

Location within the City | |

Ward of Farringdon Without Location within Greater London | |

| Population | 1,099 (2011 Census. Ward)[1] |

| OS grid reference | TQ313814 |

| Sui generis | |

| Administrative area | Greater London |

| Region | |

| Country | England |

| Sovereign state | United Kingdom |

| Post town | LONDON |

| Postcode district | EC1, EC4 |

| Dialling code | 020 |

| Police | City of London |

| Fire | London |

| Ambulance | London |

| UK Parliament | |

| London Assembly | |

The largest of the City's 25 Wards, it was reduced in size considerably after a boundary review in 2003. Its resident population is 1,099 (2011).[2]

Setting

The ward administers the land beyond the City's former western gates, including the Middle Temple, Inner Temple, Smithfield and St Bartholomew's Hospital.[3] Since the boundary changes the ward now extends further west to meet the City of Westminster at Chancery Lane.

It includes land on both sides of the (now buried) River Fleet and part of its northern boundary was formed by the Fagswell Brook,[4] which ran east to west along a line approximating to Charterhouse Street, before joining the Fleet which runs north to south under Farringdon Road and Farringdon Street.

The Ward includes a part of Holborn; the church of St Andrew Holborn and the part of its parish known as St Andrew below the Bars – with the part known as St Andrew above the Bars outside the City (in the modern London Borough of Camden). The term Bars refers to the historic boundary marks the city established when its rights or jurisdiction came to extend beyond the walls.

Ornamental boundary markers known as West Smithfield Bars, first documented in 1170[5] and 1197,[6] once marked the City's northern boundary. These stood close to the Charterhouse Street junction with St John Street (in the vicinity of the Fagswell Brook which formed the boundary before it was culverted over). Although the Smithfield Bars are lost, the ward still has Dragon boundary marks at Temple Bar, Farringdon Street and High Holborn.

History

Originally known as the Ward of Anketill de Auvergne,[7] Farringdon was named after Sir Nicholas de Faringdon, who was appointed Lord Mayor of London for "as long as it shall please him" by King Edward II.[8] The Ward had been in the Faringdon family for 82 years at this time, his father, William de Faringdon preceding him as Alderman in 1281, when he purchased the position. William de Faringdon was Lord Mayor in 1281–82 and also a Warden of the Goldsmiths' Company.[9] During the reign of King Edward I, as an Alderman and Goldsmith, William Faringdon was implicated in the arrest of English Jewry (some, fellow goldsmiths) for treason.[10]

The Ward was split in two in 1394: Farringdon Without and Farringdon Within. "Without" and "Within" denote whether the ward fell outside or within the London Wall — such designation also applied to the wards of Bridge Within and Without.

As well as goldsmiths, in medieval times the Fleet Ditch attracted many tanners and curriers to the Ward. As the City became more populous, these trades were banished to the suburbs and by the 18th century the River Fleet had been culverted and built over. In its later years, the Fleet became little more than an open sewer, and the locality was given over to slums due to undesirable odours. The modern Farringdon Street was built over it, with the Fleet Market opening for the sale of meat, fish and vegetables in 1737. Charles Dickens described the market, in unflattering terms, in his novel Barnaby Rudge, set in 1780:

"Fleet Market, at that time, was a long irregular row of wooden sheds and penthouses, occupying the centre of what is now called Farringdon Street. They were jumbled together in a most unsightly fashion, in the middle of the road; to the great obstruction of the thoroughfare and the annoyance of passengers, who were fain to make their way, as they best could, among carts, baskets, barrows, trucks, casks, bulks, and benches, and to jostle with porters, hucksters, waggoners, and a motley crowd of buyers, sellers, pick–pockets, vagrants, and idlers. The air was perfumed with the stench of rotten leaves and faded fruit; the refuse of the butchers’ stalls, and offal and garbage of a hundred kinds. It was indispensable to most public conveniences in those days, that they should be public nuisances likewise; and Fleet Market maintained the principle to admiration."[11]

In 1829, it had become necessary to widen Farringdon Street, and the market was moved to new premises at Farringdon Market. This did not thrive, and its activities were moved to West Smithfield.[12]

On 27 January 1769, the radical MP John Wilkes was elected Alderman for this Ward, while a prisoner in Newgate Prison. This was after he had repeatedly been elected as a Member of Parliament and expelled from Parliament for "outlawry"; essentially for what was considered at the time "obscene and malicious libel" against, no less than, King George III. Later, Wilkes was elected Lord Mayor of London (1774–75).

Other famous Aldermen include scions of the Childs, Hoares and Goslings banking families.

Politics

Farringdon Without is one of 25 Wards in the City of London, each electing an Alderman to the Court of Aldermen and Commoners (the City equivalent of a Councillor) to the Court of Common Council of the City of London Corporation.

The Ward is represented by Alderman Gregory Jones QC (elected February 2017, Common Councilman 2013–17) and 10 Common Councilman (elected March 2017). Alderman Gregory Jones QC has appointed John Absalom as Deputy (North) and Edward Lord OBE as Deputy (South).

Freemen of the City of London are eligible to stand for election.[13]

See also

- Farringdon

- Farringdon station

- Fleet Street

- Alpheus Morton, Deputy Alderman for Farringdon Without (1882–1923)

References

- "City of London ward population". Neighbourhood Statistics. Office for National Statistics. Retrieved 16 October 2016.

- "Local statistics – Office for National Statistics". neighbourhood.statistics.gov.uk.

- City of London Corporation Archived 21 June 2006 at the Wayback Machine – Farringdon Without.

- From a map based on Stow c 1600, (discussed in "Street-names of the City of London", (1954) by Eilert Ekwall) shows the "Fagswell Brook" south of Cowcross Street as the northern boundary of the City

- 'St John Street: Introduction; west side', in Survey of London: Volume 46, South and East Clerkenwell, ed. Philip Temple (London, 2008), pp. 203-221. British History Online http://www.british-history.ac.uk/survey-london/vol46/pp203-221 [accessed 27 July 2020].

- London, its origin and early development William Page 1923 (including reference to the primary source). Link: https://archive.org/details/londonitsorigine00pageuoft/page/178/mode/2up/search/bishopsgate

- 'Ward of Anketill de Auvergne', A Dictionary of London (1918).

- Nicholas de Faringdon served as Lord Mayor 1308-9, 1320–21, and again, 1323–24

- 'The Lord Mayors of London', Old and New London: Volume 1 (1878), pp. 396–416.

- 'Gregory's Chronicle: 1250–1367', The Historical Collections of a Citizen of London in the fifteenth century (1876), pp. 67–88.

- Dickens, Charles Barnaby Rudge (1841), Chpt. 60

- Walter Thornbury, Old and New London: A Narrative of its History, its People and its Places. Illustrated with Numerous Engravings from the Most Authentic Sources.: Volume 2. Date accessed: 27 October 2006.

- www.cityoflondon.gov.uk Archived 12 June 2011 at the Wayback Machine

External links

- Map of Early Modern London: Farringdon Ward (without) – Historical Map and Encyclopedia of Shakespeare's London (Scholarly)