Falcarragh

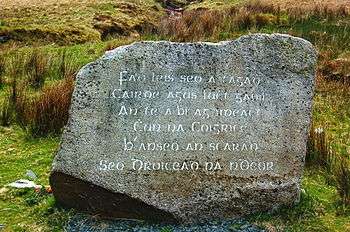

An Fál Carrach[2] (anglicized as Falcarragh), sometimes called Na Crois Bhealaí ("the crossroads") is a small Gaeltacht town and townland in north-west County Donegal, Ireland. The settlement is in the old parish of Cloughaneely.

An Fál Carrach Falcarragh | |

|---|---|

Town | |

The crossroads on Falcarragh Main Street | |

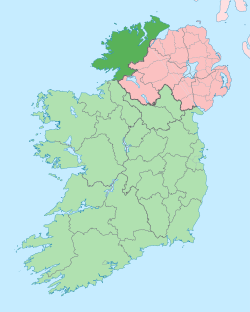

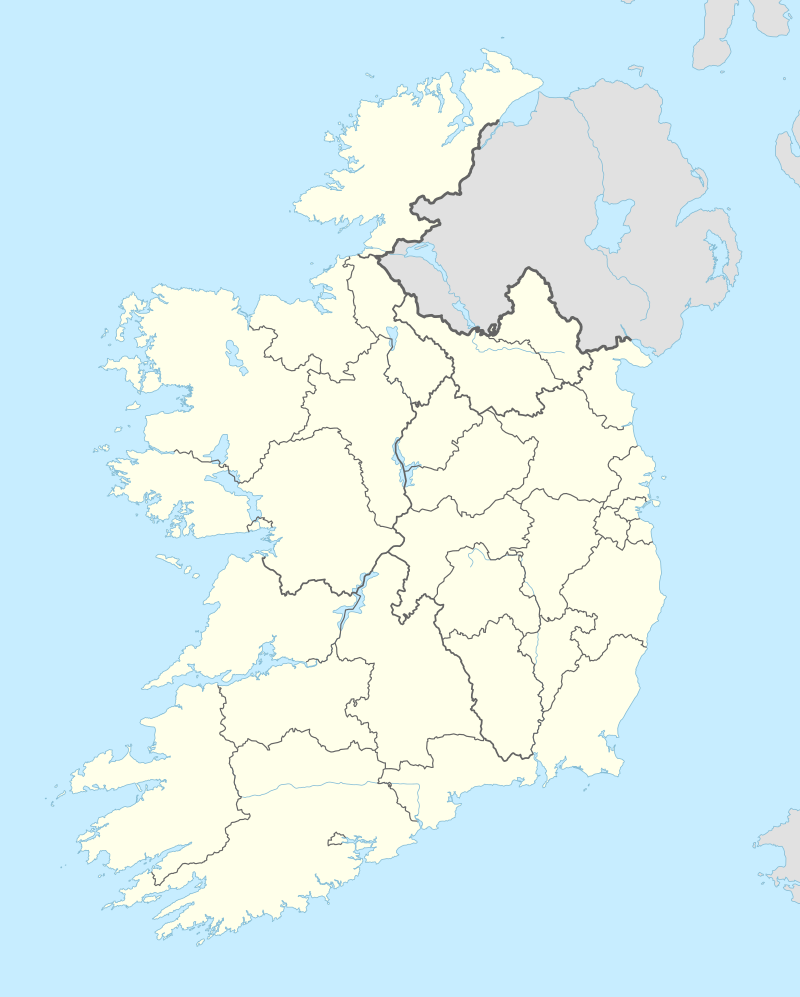

An Fál Carrach Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 55°08′11″N 8°06′18″W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| County | County Donegal |

| Government | |

| • Dáil Éireann | Donegal |

| • EU Parliament | Midlands–North-West |

| Population (2016)[1] | 764 |

| Area code(s) | 074 (+353 74) |

| Irish Grid Reference | B952329 |

| An Fál Carrach is the only official name. The anglicized spelling Falcarragh has no official status. | |

Irish language

There are 2,168 people living in the Falcarragh ED and an estimated 44% are native Irish speakers.

Etymology

The name Falcarragh (lit. An (the) Fál (Wall) Carrach (Stone), Stone Wall / Boundary) has been used since 1850, ascribed so by O' Donavan as he believed 'Na Crois Bhealaí', the Cross Roads, was too common in Ireland to allow distinction. Na Crois Bhealaí is still used by native speakers when referring to the town. On some maps it shows up as 'Crossroads' deriving from its Irish language name Na Croisbhealaí but older maps refer to it as Robinson's Town, but it is now listed as An Fál Carrach. An Fál Carrach, the main commercial town between Letterkenny and Dungloe was known in former times both as Crossroads and as Robinson’s Town. An Fál Carrach, the official name, originally referred to a little hamlet south-east of the present town, at the foot of Falcarragh hill - but gradually houses were built at the crossroads, mainly for the workers and tradespeople employed on the Olphert Estate in Ballyconnell.

History

The first recorded reference to Falcarragh appears in a report written by William Wilson, Raphoe in 1822. Wilson was the Protestant Bishop’s stewart responsible for the collection of tithes to support the Protestant clergy. He, apparently, received a hostile reception on arrival in Cloughaneely (parish) according to his account to the bishop:

- According to my intention I went to Cloughineely and on Monday about 12 o’clock arrived at a place called Falcarrow in your Lordship’s See (about five miles distant from Dunfanaghy) where I then, pursuant to advertisement, proposed holding the Court as I twice before had, but was immediately on my arrival surrounded by upwards of 150 to 300 men who had assembled merely for the purpose of preventing me from holding any Court and threatened my life if I would. Their measures I was obliged to comply with.

Slater’s Directory of 1870 provides us with valuable information about Falcarragh and its surrounding area:

- Crossroads or Falcarragh, is a village, in the parish of Tullaghbegley, and partly of Raymunterdoney, barony of Kilmacrennan, situated on the summit of a small hill near to the coast; opposite here is the Island of Torrey, nine miles distant. The places of worship are the parish church and a Presbyterian meetinghouse. A dispensary and a school are the charitable institutions. Fairs are held on the last Thursday monthly. Population in 1861 was 231.

Slater's Directory of 1881 records that the population increased to 258 inhabitants in 1871 and also tells that there was a Protestant Episcopal Church in the town. We are given some information about the local post office situated at the crossroads. Thomas Browne was Postmaster at the time and “letters from all parts arrive at ten minutes past eleven morning, and are dispatched at one afternoon.”

Landlords

From 1622 to 1921, the Olpherts were the main landlords in the district, Sir John Olphert being the last Olphert landlord, who died in 1917. The tallest Celtic cross in Ireland is located near Falcarragh.

Transport

- Falcarragh railway station opened on 9 March 1903, closed for passenger traffic on 3 June 1940 and finally closed altogether on 6 January 1947.[3] The 1992 movie "The Railway Station Man" starring Donald Sutherland & Julie Christie was partly filmed at the station.

- There are two bus services close to Falcarragh and have stops in Falcarragh

Notable people

- Eithne Coyle, a leading figure within Cumann na mBan, was born in the nearby village of Killult.[4]

- Ciaran Berry, the poet, grew up in Falcarragh.[5]

- Hugh McFadden, the poet, literary critic and journalist, spent part of his childhood in Falcarragh and Newtown, where his father's family originated.

- Michael Dougherty, soldier

See also

- List of populated places in Ireland

- Bridge of Tears

References

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements An Fál Carrach". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 5 June 2018.

- Placenames (Ceantair Ghaeltachta) Order 2004. As to the meaning of the name, see Deirdre and Laurence Flanagan, Irish Place Names, Gill & Macmillan, 2002.

- "Falcarragh station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Retrieved 13 October 2007.

- McCoole, Sinéad (2003). No ordinary women: Irish female activists in the revolutionary years, 1900-1923. O'Brien Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780299195007.

- "Donegal poet takes US literary prize". Donegal Democrat. 12 November 2012. Retrieved 12 November 2012.