Clonmany

Clonmany (Irish: Cluain Maine)[3] is a village in north-west Inishowen, in County Donegal, Ireland. The area has many local beauty spots, while the nearby village of Ballyliffin is famous for its golf course. The Urris valley to the west of Clonmany village was the last outpost of the Irish language in Inishowen. In the 19th century, the area was an important location for poitín distillation.

.jpg)

.jpg)

Clonmany Cluain Maine | |

|---|---|

Village | |

| |

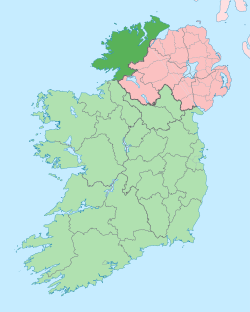

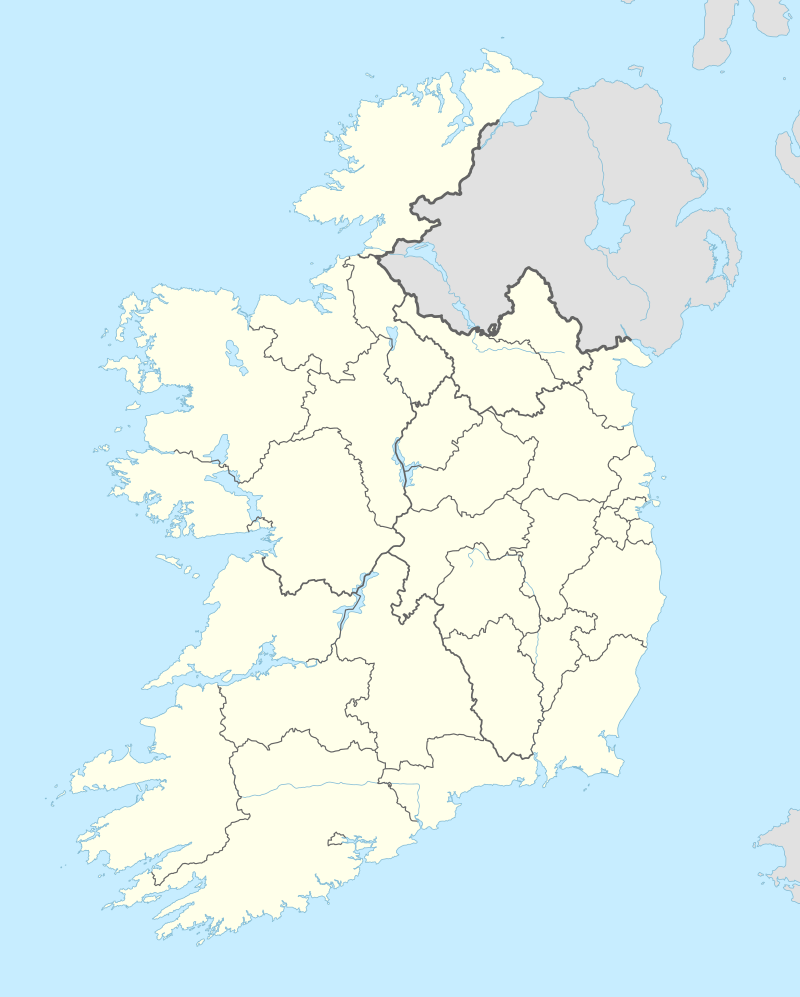

Clonmany Location in Ireland | |

| Coordinates: 55°15′45″N 7°24′45″W | |

| Country | Ireland |

| Province | Ulster |

| County | County Donegal |

| Government | |

| • Dáil Éireann | Donegal |

| Area | |

| • Total | 95.01 km2 (36.68 sq mi) |

| Population (2016)[2] | |

| • Total | 428 |

| Time zone | UTC+0 (WET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-1 (IST (WEST)) |

| Area codes | 074, +353 74 |

| Irish Grid Reference | C374463 |

Name

The name of the town in Irish - Cluain Maine has been translated as both "The Meadow of St. Maine" and "The Meadow of the Monks", with the former being the more widely recognized translation. The village is known locally as "The Cross", as the village was initially built around a crossroads.

History

The parish was home to a monastery that was founded by St. Columba.[4] It was closely associated with the Morrison family, who provided the role of erenagh. The monastery was home to the Míosach a copper and silver shrine, now located in the National Museum of Ireland in Dublin. Details of local history and traditions were recorded in "The Last of the Name", recorded by schoolteacher Patrick Kavanagh (NOT the poet) from stories by Clonmany local, Charles McGlinchey.

The village claims to be the youngest in Inishowen. The 18th Century travel writer - Richard Pococke - did not mention the village when he toured the area in 1752.[5] The village is mentioned in Topographia Hibernica, published in 1795.[6] It did not feature in the census of 1841 or 1851. In the 1861 census, 112 inhabitants are recorded as living in Clonmany in 21 houses. A further 3 houses are recorded as uninhabited.[7]

The Poitin Republic of Urris

In the early 19th century, Urris - a valley three miles west of Clonmany - became a center of the illegal poitín distillation industry. The Urris Hills were an ideal place for poitín-making. The area was surrounded by mountains and only accessible through Mamore Gap and Crossconnell. Notwithstanding its remote location, Londonderry was about 16 miles away, providing a major market for the trade. To protect their lucrative business, the locals barricaded the road at Crossconnell to keep out revenue police, thus creating the "Poitin Republic of Urris". This period of relative independence lasted three years. But in 1815, the authorities re-established control of the Urris Hills and brought this short period of self-rule to an end.[8][9]

The 1840 earthquake

In 1840, the village experienced an earthquake, a comparatively rare event in Ireland. The shock was also felt in the nearby town of Carndonagh. The Belfast Newsletter from Tuesday, January 28, 1840 reported that "In some places those who had retired to rest felt themselves shaken in their beds, and others were thrown from their chairs, and greatly alarmed."[10]

The "Waterloo Priest"

From 1829 to 1853, the Parish of Clonmany was served by Fr. William O’Donnell – the “Waterloo Priest”. He was born in Cockhill, Buncrana in 1779. In 1802 he entered Maynooth College, but upon graduation he declined the opportunity to become a priest. Instead he joined the army and campaigned in the Peninsular war, where he fought in the battles of Vittoria, Roncesvalles and Pyrenees. Later, he fought at the Battle of Waterloo.

In 1819, he was ordained and served as parish priest in Lower Fahan and Desertegney. In 1829, he was appointed parish priest in Clonmany, a post he held until his death in 1856. His time at Clonmany was marked by a deep devotion to the people of the parish. He established five National schools in the Parish. He campaigned strongly for the rights of the local people. In 1838, during the latter years of the tithe war, he was jailed for non-payment of tithes to the Church of Ireland.[11] He was jailed in Lifford Prison and he became a national focal point in the campaign against the tithe system. In 1846, at the beginning of the famine, he set up a Relief Committee for Clonmany.[12] He died February 10, 1856 in his residence in Clonmany aged 77.[13]

The Famine

Like much of Ireland, the surrounding areas of Clonmany were devastated by the potato blight leading to an appalling loss of life among the rural poor. As early as December 1845, there were warning signs that the potato crop around Clonmany was failing and disaster was imminent. The Church of Ireland Rector of Clonmany - Rev. George H. Young - had reported to the Banner of Ulster Newspaper that "one-half of all (the potatoes) dug was, more or less, diseased. I am sure l am correct in stating, that not less than three-fourths of the crop has been already lost. How or from whence seed is to be provided, I know not".[14]

Local clergy - both Roman Catholic and Protestant - made valiant efforts to raise funds and provide relief but the magnitude of the crop failure and the spread of diseases like Dysentery meant that these efforts were overwhelmed. By January 1847, a local relief committee was activity raising funds to provide emergency food supplies.[15] The committee contacted local landlords seeking financial support and debt forgiveness for tenants in rent arrears. The response from landlords was varied; some were willing to provide help; others were not. Local landlord - Michael Loughrey of Binion hall - contributed to the fund. John Harvey and Mrs Merrick wrote to Fr. O'Donnell - parish priest and chairman of the committee - indicating that they would not support the relief efforts until rent arrears and other costs were paid first. This correspondence was published in the Derry Journal.[16] Around the same time, the Derry Sentinel reported that Clonmany was experiencing a death rate of five to six individuals each day.[17]

Land Wars in the 19th Century

Throughout the 19th century, the rural areas surrounding Clonmany experienced significant conflict over the issues of land ownership and tenant rights. During the 1830s, the Ribbon men and night-walkers were active in the area. This was a popular Catholic movement that protested against landlords and their agents. In February 1832, crowds of up to three thousand local tenants attacked the properties of two prominent landlords; Michael Doherty of Glen House and Neal Loughrey of Binnion. The protesters demanded a reduction in rents and the elimination of tithe payments to the Church of Ireland.[18][19] Unrest also broke out in Spring 1833. A local man by the name of O'Donnell had his house destroyed by rioters after he took over the property from an evicted tenant. Rioters also destroyed the forge of the local blacksmith (by the name of Conaghan) after he had provided services to the tithe agent. Rioters also smashed the property of local people who were employed directly by landlords.[20] In February 1834, the army posted to the village a detachment of the 1st Royals Regiment from the Londonderry Garrison to provide support to the civil authorities.[21] Further unrest occurred out in April 1834 when large crowds rioted and destroyed property.[22]

Violence again broke out in June 1838, when a crowd of local people attacked the house where an absentee landlord - Mrs Merrick - was temporarily staying. At the time, she was visiting the area to view her properties.[23] The home of Mrs Merrick's bailliff - Hugh Bradley - was attacked on September 1838. Bradley was badly beaten and his house was ransacked by a group of armed men. Mrs Merrick later offered a reward of £100 for any information regarding the attacks on Bradley.[24] In 1852, local tenants attacked Charles McClintock. He was a civil engineer who was surveying local properties on behalf of Michael Doherty, one of the main landlords in the area. Attackers fired shots into McClintock's bedroom and pelted the house with rocks.[25]

On occasions, the violence took on a sectarian nature. In January 1861, the Protestant chapel in Clonmany was attacked. The windows were smashed and the door was destroyed.[26]

During the 1880s, evictions and protests against landlordism were relatively common events. In January 1881, four local men were arrested for unlawful assembly and riotous behavior after they attacked a bailiff employed by a landlord called Harvey.[27] The Land League established a Clonmany branch, which was named after the founder of the organization - Michael Davitt.[28] Its activities were often reported by the Derry Journal. The newspaper recorded a steady flow of protests and evictions throughout the 1880s.[29][30][31] The local Catholic clergy were active in defending the rights of tenants and in concert with the Land League they regularly pleaded the cases of individual tenants to local Landlords. In December 1885, the clergy and land league sent a deputation to Mr. Loughrey, a landlord who had a difficult relationship with his tenants. When the Land League representatives remarked on the low value of land, Mr. Loughrey replied "the tenants were too cheaply rented, that they wanted to drive me and my family to the workhouse, but I will take steps to draw a good many there along with me".[32] The Loughrey estate was one of the largest in the area.

Evictions were often met with met with organized protest. To mitigate these protests, landlords combined to organize joint mass evictions supported by a sizable police and military presence. This often meant that tenants had accumulated rent arrears for several years before the evictions took place. For example, on a single day in June 1881, 80 armed police entered Clonmany to oversee a series of evictions in the surrounding area. These evictions were collectively organized by four local landlords. A protest march was organized by the Land League and the local Priest - Fr. Maguire - who figured prominently in the opposition to evictions. The evictions proved to be a tortuous process, with bailiffs poorly informed about the precise location of properties, miss-identification of tenants and disputes about whether the rents had actually been paid or not.[33] In March 1882, the Derry Journal reported that a further 18 evictions had taken place on the Loughrey estate which made over 100 individuals homeless.[34]

The eviction of Catherine Doherty in August 1882 was typical. She was a widow who lived in Cleagh, a townland just outside Clonmany. She had accumulated significant arrears before her landlord took legal proceedings against her. The Derry Journal recorded the event.

"The first house visited was that of widow Catherine Doherty. She owed two years’ rent. A writ was served on her May, 1881, Just two days after the rent became due. She tried to have a settlement effected but all in vain. She offered two years’ rent (£8 11s) with the half the costs, but that offer was flatly refused by the agent, who would accept nothing less than the entire amount of rent and costs, to be paid before he would leave the house. The Rev. Father O’Doherty, P.P., Father Maguire, and Father McCullagh were in attendance during the first eviction, and reasoned with Mr. Harvey for long time. Men were ordered clear out the furniture. This occupied a considerable time. The usual formalities being gone through of binding up the doors, giving possession to the agent. The ranks of the soldiers and police were ordered (to) march to Rooskey, where the next eviction was (to) come off. Denis O’Donnell, three in family, was the tenant. His time of redemption having expired"[35]

Concerns about extent of evictions around the Clonmany was raised in parliament by the Irish Nationalist MP O'Donnell. In March 1882, He asked the Chief Secretary to the Lord Lieutenant of Ireland if he knew about:

"the extensive evictions of tenants, for arrears of rent, are taking place, or are about to take place, in the districts of Clonmany, Binnion, Garryduff, Adderville, and Cardonagh, in the county of Donegal; whether it is true that meetings of the inhabitants to protest against these evictions, and to invite public sympathy with poor tenants, on the ground of their incapability to pay the unreduced rents accumulating since the years of distress, have been prohibited by the Government".[36]

In May 1883, Thomas Sexton (the Irish Nationalist MP for Sligo) asked a question in parliament regarding the conduct of the Royal Irish Constabulary towards evicted tenants in Clonmany. Mr. Sexton reported that a tenant farmer named Doherty was prevented by the police from erecting huts to shelter evicted families. He reported that 23 families comprising 108 people had taken refuge in Clonmany with as many as four families sleeping into one small house. Sir George Trevelyan the Chief Secretary for Ireland, disputed this account. He said that Doherty wanted to build his hut near some evicted farms, and this would require the Police to build an outpost to guard these properties. This construction would impose costs on the local community.[37][38]

In September 1885, local landlords sent in four "Emergency Men" to take possession of farms where tenants were previously evicted. After the tenants were removed from their homes, they continued to use the land to grow crops. The "Emergency men" arrived to take possession of these crops. In order to protect these new arrivals, the police were required to station half a dozen men in the district.[39]

Protests often targeted local individuals who had assisted in evictions. In July 1888, seven local men were accused of interfering with the burial of Patrick Cavanagh. He was a former veteran of the Crimean War who worked on the Loughery estate. Cavanagh had become unpopular with the local residents after he became the caretaker of the properties of recently evicted tenants. The seven accused men were John O'Donnell, William Harkin, William Gubbin, Patrick Gubbln, Owen Doherty, from Clonmany; Constantine Doherty, from Cleagh; and Michael Doherty, from Cloontagh. The men were accused of filling up the newly dug grave with large stones and preventing the body from entering the graveyard. No one in the village was prepared to supply a coffin for Cavanagh. The local Catholic Clergy begged the demonstrators to allow the burial to proceed. The demonstrators threatened that if the body were buried in the graveyard that they would dig it up. Eventually, the Local Government Board issued an administrative order to remove the body for interment in the Carndonagh Workhouse cemetery.[40][41][42] The case aroused much interest and was reported widely across the United Kingdom.[43] Two of the accused - Owen Doherty and Constantine Doherty - were found guilty of unlawful assembly and sentenced to six months imprisonment. The remaining men were discharged.[44]

First World War

The area around Clonmany has strong military associations. In 1914, the British Army opened a training camp named Glenfield Camp, which was located near Glen House, Straid. Up to 5,000 soldiers were garrisoned at Glenfield, including battalions from the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers, the Devonshire Regiment and the Royal Irish Fusiliers. There were also military establishments in Leenan and Dunree. The latter fort was first established during the Napoleonic wars. Both Leenan and Dunree were used to guard the entrance of Loch Swilley, which was used to station part of the Royal Navy's Atlantic Fleet. These latter two camps formed part of the Treaty Ports, which the UK Armed Forces continued to use after the Irish Free State was established. These camps were transferred to the Irish Armed Forces in October 1938.[45]

Irish War of Independence

In early 1920 an IRA company was established in Clonmany. It formed part of the 2nd Battalion of the Donegal IRA which was based on Carndonagh. The battalion also included companies from Culdaff, Malin, Malin Head and Carndonagh.[46] In August 1920, the IRA conducted extensive raids on houses throughout the district to collect firearms held by local residents.[47] In November 1920, British armed forces reciprocated, twice raiding the village and the surrounding area, searching almost every home, and in some cases, ripping up floorboards. The search uncovered considerable quantities of ammunition.[48][49]

In April 1921, Joseph Doherty, a farmer from Lenan, was found guilty for possessing firearms "not under effective military control." During a search at the home of Doherty's mother, a single-barreled breech-loading shotgun was found concealed in a corn stack. Doherty made a statement indicating that he knew nothing about the gun, which "must have been planted in the corn stack by someone who wished to get him into trouble." During the trial, Doherty refused to recognize the court. The judge remarked that the accused's refusal to recognize the court had only one interpretation, that he belonged to an illegal society.[50]

The most notorious incident to occur in Clonmany during the conflict happened on 10 May 1921, when two Royal Irish Constabulary constables - Alexander Clarke and Charles Murdock - were kidnapped and murdered by the IRA. Both men were stationed at the RIC Barracks in Clonmany. They went for a walk in the evening but were kidnapped near Straid. Clarke was shot and thrown into the sea, and his body washed up on the seashore near Binion the next day. Constable Murdock, who was from Dublin, reportedly survived the initial attack, escaped[51] and sought refuge among residents of Binion. However, he was betrayed to the IRA who murdered him. His body has never been found. Local tradition suggests that he was buried in a bog near Binion hill.[52] In June 1921, a military court was held in Clonmany to conduct a postmortem for PC Clarke. The court found that Clarke had died from a gunshot wounds to the heart, jaw and neck and that his firearm and ammunition was missing. At the time of his death, Clarke was 23 years old and unmarried.[53]

A few days after the murders of Constables Murdock and Clark, six bridges on the road between Buncrana and Clonmany were destroyed with explosives. These attacks effectively isolated much of North Inishowen. It also significantly delayed the repatriation of the body of Constable Clarke. The Police were forced to commandeer local labour to make temporary repairs to bridges in order to transport part the body to England.[54]

A few weeks later, on July 10, 1921 Crown Forces raided a number of houses in Clonmany looking for Sinn Féin activists. Three unnamed young men from the village were arrested, but were released shortly afterwards and allowed to return home.[55]

In July 1921, railway workers at Clonmany railway station refused to transport British Soldiers. The soldiers were removed from the train and sent back to Leenan fort.[56]

Irish Civil War

The conflict was fought between two opposing groups of Irish nationalists: those who supported the Anglo-Irish Treaty under which the Irish Free state was established, and the republican opposition, for whom the Treaty represented a betrayal of the Irish Republic. Clonmany was captured by Free State Forces on July 1, 1922. A train was commandeered from Buncrana. It moved troops to Clonmany and later onto Carndonagh. The capture of Clonmany was peaceful. When the troops arrived in Carndonagh, a gun battle broke out with Anti-Treaty Irregulars, who had taken up positions in the Workhouse. The Irregulars agreed to surrender after the Free State Army had opened fire with a machine gun.[57]

Second World War

During the mid-20th century, a cottage based textiles industry had developed around Clonmany. During the war, many local women were contracted to make shirts for the British Army.[58] These contracts were allocated to cottage producers by firms in Buncrana and Derry that were unable to manage the large orders from the British War Office.

In August 1940, a body washed up on the shore at Gaddyduff, Clonmany. The body was recovered by Mr. Denis Kealey, a farmer's son, of Leenan. A postcard was found on the body indicating that the victim was Giovanni Ferdenzi ; an Italian migrant to the UK, who lived in Kings Cross. He was previously held at Worth-Mills Internment Camp. The cause of death was heart failure due to exposure. The body was given Catholic burial at Clonmany. Giovanni was being transported to Canada on SS Arandora Star, which was sunk by a U-Boat on 2 July 1940.[59] A second unidentifiable body was washed ashore on Ballyliffin strand.[60]

In March 1946, eight mines were destroyed by the Irish Army after they had floated close to the shoreline between Ballyliffin and Clonmany. The mines appeared after a heavy storm.[61]

Floods and Storms

The village has periodically suffered from storms coming off the Atlantic Ocean. These storms have caused flooding, typically after heavy rainfall during the summer months, On May 28, 1892, Clonmany experienced three hours of torrential rain, that caused the banks of the Clonmany river to break. Several hundred acres of land was flooded, with a large loss of crops and livestock. The townlands of Crossconnell. Tanderagee, Cleagh, Cloontagh, and Gortfad were all heavily flooded.[62] Two years later, in December 1894, the area was hit by another violent storm. The church roofs in Clonmany and Urris were damaged. Many thatched cottages had their roofs blown away entirely. A large amount of agricultural production was destroyed.[63]

After a period of heavy rain during September 1952, the banks of the Clonmany river broke, flooding a number of corn fields. The area around Crossconnell was particularly affected.[64] In August 1952, the banks of the Clonmany river again broke after a period of very heavy rain. The rains coincided with a high tide, which further exacerbated the flood. Water reached the houses within the village itself.[65] In late August 2017, the village was severely affected by flooding brought on by an extended period of heavy rains. In a seven-hour period, over 80 millimeters of rain was recorded.[66] Some residents were cut off due to rising river levels and had to be rescued from their homes. The R238 road, which links the village with Dumfree, was closed after a bridge collapsed.The Irish defense forces were deployed to help with rescue and clean up efforts.[67] In 2014, the National Preliminary Flood Risk Assessment Report highlighted Clonmany and its surrounding areas as one of 28 areas that may need flood protection as sea levels are expected to rise due to climate change.[68]

Places of Interest

St. Mary's Roman Catholic Church - A very good example of a pre-emancipation Catholic Church. The building was started around 1814, with an extension to north to form T- plan built in 1833. A three-stage tower on square-plan was built in 1843.

Clonmany Church of Ireland Parish Church - Located in Straid, just outside the village. Built in 1772 and altered in 1830. The building is now a ruin, but is accessible to visitors. The graveyard also contains a number of graves of early eighteenth-century date and maybe earlier, that predates the present edifice and may be associated with an earlier church on the site.

Clonmany Bridge - A triple-arch slightly humpbacked bridge carrying the road to Urris over the Clonmany river, built around 1800. It was in existence in 1814, when it was mentioned in the 'Statistical Account of the Parish of Clonmany'.

Climate

The location of Clonmany on the Inishowen peninsula, and bordering Lough Swilly with views of the Atlantic provides the Clonmany area with a moderate climate; with temperate, mild summers, and winters that rarely go below freezing. The average temperatures for the area are usually warmer than the national average in winter, and cooler than the national average in summer.

Education

Clonmany has four primary schools, Clonmany N.S. (with a new state of the art school), Scoil Naomh Treasa (also known as Tiernasligo N.S. locally), Scoil Phádraig at Rashenny, and Scoil na gCluainte, or Cloontagh National School. Most students from these schools go on to attend secondary level education at Carndonagh Community School in Carndonagh, with most of the remainder attending Scoil Mhuire or Crana College in Buncrana. There was a national school in Crossconnell, which dated from the 19th century. However, it was closed in the late 1960s.

Transport

Clonmany railway station opened on 1 July 1901, but finally closed on 2 December 1935.[69] The station was a stop on the Londonderry and Lough Swilly Railway Company (The L&LSR, the Swilly) that operated in parts of County Londonderry and County Donegal.

Culture & tourism

Clonmany is host to the annual McGlinchey summer school, which attracts many visitors to its exhibitions and lectures on local history. Another attraction is the Clonmany festival, held annually during the week of the Irish August public holiday. The Clonmany Agricultural Show and Sheepdog Trials takes place on the Tuesday of festival week, with visitors from all over Inishowen and the Northwest of Ireland.

Sports

The Clonmany Tug of War team has enjoyed remarkable success over many years. The team was formed in 1946, and has achieved six world gold medals and twenty All Ireland titles.[70]

The village has a soccer team - Clonmany Shamrocks.[71]

Gallery

Rural Clonmany

Rural Clonmany Snowflake shop

Snowflake shop Main Street Clonmany

Main Street Clonmany McCauley's Public House in Clonmany

McCauley's Public House in Clonmany Main street, including the Centra supermarket and the local Catholic church

Main street, including the Centra supermarket and the local Catholic church

See also

- List of populated places in Ireland

- Market Houses in Ireland

References

- Census 2002 - Volume 1: Population Classified By Area, Central Statistics Office, Dublin, 2003

- "Census 2016 Sapmap Area: Settlements Clonmany". Central Statistics Office (Ireland). Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- "Cluain Maine/Clonmany". Placenames Database of Ireland. Government of Ireland - Department of Arts, Heritage and the Gaeltacht and Dublin City University. Retrieved 10 June 2018.

- Seward, William Wenman (1797). Topographia Hibernica, or The topography of Ireland, ancient and modern. Alexander Stewart.

- Pococke, Richard (1892). Pococke's Tour in Ireland in 1752. Hodges, Figgis.

- Topographia Hibernica. Dublin: Printed by Alex. Stewart. 1795.

- "Parish Census 1841,1851 and 1861". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Inishowen – the Poitin Republic of Urris". 2013-09-02.

- Atkinson, David; Roud, Steve (2016). Street Ballads in Nineteenth-Century Britain, Ireland, and North America: The Interface Between Print and Oral Traditions. London: Routledge. p. 140. ISBN 9781317049210.

- Belfast Newsletter 1738-1938, Tuesday, January 28, 1840; Page: 4

- "The tithe curse— A catholic clergyman incarcerated in the north". Freemans Journal. August 1838.

- Maghtochair (1867). Inishowen: Its History,traditions,& Antiquities. the Journal Office.

- "Catholic Church". The Ulsterman. 27 February 1856.

- "Failure of Potato Crop". Banner of Ulster. 30 December 1845.

- "Voluntary relief". Northern Star and Leeds General Advertiser. 9 January 1847.

- "Parish of Clonmany". Derry Journal. 13 January 1847.

- "Fever and Dysentery". Vindicator. 30 January 1847.

- "Whiteboyism in Ennishowen". Warder and Dublin Weekly Mail. 4 February 1832.

- "Donegal Assizes". Enniskillen Chronicle and Erne Packet. 2 August 1832.

- "local report". Belfast Newsletter. April 9, 1833.

- "Ennishowen" (21 February 1834). Belfast Newsletter.

- "Ireland (from our own correspondant)". The Times. 25 April 1834.

- "Irish Outrages". Freemans Journal. June 15, 1838.

- "£100 reward". Londonderry Journal. 2 October 1838.

|access-date=requires|url=(help) - "Outrage in Ennishowen". Freemans Journal. February 6, 1852.

- "Outrage in Clonmany" (17 January 1861). Belfast Newsletter.

- "Land league proceedings in Enniskillen" (14 January 1881). Belfast Newsletter.

- "Clonmany (Davitt) Branch". Derry Journal. 21 October 1885.

- "Ladies Land League, Clonmany Donegal". Derry Journal. 1 June 1881.

- "Clonmany (Country Donegal) Branch, Land League". Derry Journal. 1 June 1881.

- "Irish National League, Clonmany Branch". Derry Journal. 10 June 1885.

- "Irish National League, Clonmany Branch". Derry Journal. 9 December 1885.

- "Evictions in Clonmany". Derry Journal. 22 June 1881.

- "The evictions in Donegal". Derry Journal. 24 March 1882.

- "Evictions in Clonmnay, County Donegal". Derry Journal. 21 August 1882.

- Evictions (Ireland)—Estates Of The Irish Society. London: Hansard. 13 March 1882.

- Hansard's Parliamentary Debates. London. 1883. p. 699.

- "Evictions in Ireland". The Times. 23 May 1883. Retrieved 27 May 2020.

- "The Evicted Farms in Donegal: The Arrival of Emergency Men". The Morning News. 12 September 1885.

- "Burial prevented in Ireland". St James's Gazette. 30 June 1888.

- "Boycotting a Corpse". Northern Constitution. 21 July 1888.

- Hurlbert, William (1888). Ireland Under Coercion vol.2. Edinburgh: David Douglas.

- "Refusing a corpse to be buried". Glasgow Evening Citizen. 29 June 1888.

- "BARBAROUS CONDUCT. NO BETTER THAN SAVAGES". Londonderry Sentinel. 19 July 1888.

- "Loch Swilly Forts Evacuated". Belfast News-Letter. 4 October 1938.

- ROINN COSANTA. BUREAU OF MILITARY HISTORY, 1913-21. STATEMENT BY WITNESS. DOCUMENT NO. W.S. 1516.

- "Extensive raids for Arms". Irish Times. 3 September 1920.

- "Military Raids in Inishowen - Several Houses Searched". Donegal News. 20 November 1920.

- "Ammunition seized". Belfast Newsletter. 20 November 1920.

- "GUN IN CORN STACK. TRIAL OF DONEGAL. FARMER. DECLINES TO RECOGNISE COURT". Ballymena Weekly Telegraph. 16 April 1921.

- Lynchage, Patrick. "Statement by witness, document number W.S. 1515" (PDF). Defence forces of Ireland-military archives.

- "MURDERED AND THROWN INTO SEA. FATE OF DONEGAL CONSTABLES". Northern Whig. 11 May 1921.

- "Recent Clonmany tragedy - findings of military court". Fermanagh Herald 1. June 11, 1921.

- "The Lawless North Wesr". Belfast Newsletter. 14 May 1921.

- "Military Raids in Clonmany". Derry Journal. 13 July 1921.

- "The railway hold up". Belfast newsletter. 17 July 1921.

- "Inishown penisula cleared of Irregulars". Belfast Newsletter. July 1, 1922.

- "Cottage made shirts for Troops". Irish Press 1. March 8, 1940.

- "Inquest on Arandora Star victims". Irish Press. August 14, 1940.

- "Catholic Burial". Donegal Democrat. August 14, 1940.

- "Mines ashore in Donegal". Irish Independent. March 7, 1946.

- "Great Floods in Innishowen". Derry Journal. 30 May 1892.

- "The storm in Clonmany". Derry Journal. December 28, 1894.

- "Flooding in Clonmany District". Derry Journal. September 26, 1924.

- "Cloudburst in Clonmany". Donegal News. August 23, 1952.

- "INISHOWEN FLOODING: 'MIRACLE' ESCAPES ON A PENINSULA DEVASTATED". Donegal Daily. August 2017.

- "Minister says emergency agency should be set up as army pitches in for second day in Donegal". The Journal.IE. August 2017.

- "Twenty-eight areas at risk of flooding - report". Donegal News. February 7, 2014.

- "Clonmany station" (PDF). Railscot - Irish Railways. Retrieved 2007-09-17.

- "Clonmany Tug of War Team: A History - 50 Years on". Clonmany. Retrieved 3 July 2017.

- "Clonmany Shamrocks FC". Retrieved 9 June 2020.