Etymology of Edinburgh

The name Edinburgh is used in both English and Scots for the capital of Scotland; in Scottish Gaelic, the city is known as Dùn Èideann. Both names are derived from an older name for the surrounding region, Eidyn. It is generally accepted that this name in turn derives ultimately from the Celtic Common Brittonic language.[1][2][3]

| Look up Edinburgh in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Eidyn

Several medieval Welsh sources refer to Eidyn. Kenneth H. Jackson argued strongly that "Eidyn" referred exclusively to the location of modern Edinburgh,[4] but others, such as Ifor Williams and Nora K. Chadwick, suggest it applied to the wider area as well.[1][2] The name "Eidyn" may survive today in toponyms such as Edinburgh, Dunedin, and Carriden (from Caer Eidyn, from which the modern Welsh name for Edinburgh, Caeredin, is derived), located eighteen miles to the west.[3]

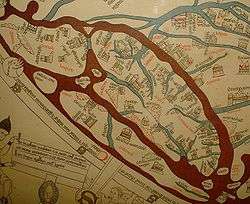

Present-day Edinburgh was the location of Din Eidyn, a dun or hillfort associated with the kingdom of the Gododdin.[5] The term Din Eidyn first appears in Y Gododdin, a poem that depicts events relating to the Battle of Catraeth, thought to have been fought circa 600. The oldest manuscript of Y Gododdin forms part of the Book of Aneirin, which dates to around 1265[6] but which possibly is a copy of a lost 9th-century original. Some scholars consider that the poem was composed soon after the battle and was preserved in oral tradition while others believe it originated in Wales at some time in the 9th to 11th centuries.[7] The modern Scottish Gaelic name "Dùn Èideann" derives directly from the British Din Eidyn. The English form is similar, appending the element -burgh, from the Old English burh, also meaning "fort".[8]

Some sources claim Edinburgh's name is derived from an Old English form such as Edwinesburh (Edwin's fort), in reference to Edwin, king of Deira and Bernicia in the 7th century.[9] However, modern scholarship rejects this idea, since the form Eidyn predates Edwin.[8][10] Stuart Harris in his book The Place Names of Edinburgh declares the "Edwinesburh" form to be a "palpable fake" dating from King David I's time.[11]

Edinburgh's original royal charter granting royal burgh status is lost and the first documentary evidence of the medieval burgh is a royal charter, c. 1124–1127, by King David I granting a toft in burgo meo de Edenesburg to the Priory of Dunfermline.[12] This suggests that the town came into official existence between 1018 (when King Malcolm II secured the Lothians from the Northumbrians) and 1124.[13] The founding charter of Holyrood Abbey refers to the recipients (in Latin) as "Ecclisie Sancte Crucis Edwinesburgensi", by the 1170s King William the Lion was using the name "Edenesburch" in a charter (again in Latin) confirming the 1124 grant of David I. Documents from the 14th century show the name to have settled into its current form; although other spellings ("Edynburgh" and "Edynburghe") appear, these are simply spelling variants of the current name.

Other names

Auld Reekie

The city is affectionately nicknamed Auld Reekie, Scots for Old Smoky, for the views from the country of the smoke covered Old Town.[14][15] Robert Chambers, who asserted that the sobriquet could not be traced before the reign of Charles II, attributed the name to a Fife laird, Durham of Largo, who regulated the bedtime of his children by the smoke rising above Edinburgh from the fires of the tenements.[16][17][18]

Athens of the North

Some have called Edinburgh the Athens of the North for a variety of reasons. The earliest comparison between the two cities showed that they had a similar topography, with the Castle Rock of Edinburgh performing a similar role to the Athenian Acropolis. Both of them had flatter, fertile agricultural land sloping down to a port several miles away (respectively Leith and Piraeus). Although this arrangement is common in Southern Europe, it is rare in Northern Europe. The 18th century intellectual life, referred to as the Scottish Enlightenment, was a key influence in gaining the name. Such beacons as David Hume and Adam Smith shone during this period. Having lost most of its political importance after the Union, some hoped that Edinburgh could gain a similar influence on London as Athens had on Rome. Also a contributing factor was the later neoclassical architecture, particularly that of William Henry Playfair, and the National Monument. Tom Stoppard's character Archie, of Jumpers, said, perhaps playing on Reykjavík meaning "smoky bay", that the "Reykjavík of the South" would be more appropriate.[19]

Dunedin

Edinburgh has also been known as Dunedin, deriving from the Scottish Gaelic, Dùn Èideann. Dunedin, New Zealand, was originally called "New Edinburgh" and is still nicknamed the "Edinburgh of the South".

Other nicknames

The Scots poets Robert Burns and Robert Fergusson sometimes used the Latin form of the city's name, Edina, in their work. Ben Jonson described it as Britaine's other eye,[20] and Sir Walter Scott referred to the city as yon Empress of the North.[21]

Other Scots dialect variants include Embra, or Embro[22] and Edinburrie.

Within Scotland itself, Edinburgh is also sometimes referred to just as "the Capital".

References

- Williams 1972, p. 47; 64.

- Chadwick, p. 107.

- Dumville, p. 297.

- Jackson 1969, pp. 77-78.

- Gardens of the 'Gododdin' Craig Cessford Garden History, Vol. 22, No. 1 (Summer, 1994), pp. 114-115 doi:10.2307/1587005

- "The Book of Aneirin". Maryjones.us. Archived from the original on 7 June 2009. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Evans 1982, p. 17.

- Room, pp. 118–119.

- Blackie, Geographical Etymology: A Dictionary of Place-names Giving Their Derivations, 68.

- Gelling, Nicolaisen and Richards, pp. 88–89.

- Harris, Stuart (1996). The Place Names Of Edinburgh. London. p. 237. ISBN 1904246060.

- Barrow, Geoffrey (1999). The Charters of King David I: The Written Acts of David I King of Scots …. p. 63. ISBN 978-0851157313.

- Campbell, A. (January 1942). "Two Notes on the Norse Kingdoms in Northumbria". The English Historical Review, Vol. 57, No. 225, pp. 85-97

- Scott, Walter. The Abbot. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Carlyle, Thomas. Historical Sketches... pp. 304–305. Retrieved 11 August 2011.

- Grant, James. Old and New Edinburgh. Retrieved 7 August 2011.

- Chambers, Robert. Traditions of Edinburgh. p. 168. Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- "Reekie". Retrieved 8 August 2011.

- Stoppard, Tom. Jumpers, Grove Press, 1972, p. 69.

- "The Cambridge Companion to Ben Jonson". Retrieved 10 October 2010.

- Marmion A Tale of Flodden Field by Walter Scott Archived 26 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine. Retrieved 17 April 2007.

- "For Embro' wells are grutten dry" Elegy On the Year 1788, Robert Burns

Bibliography

- Blackie, Christina (1887), Geographical Etymology: A Dictionary of Place-names Giving their Derivations, John Murray, ISBN 0-7083-0465-6, retrieved 1 August 2011

- Chadwick, Nora K. (1968), The British Heroic Age: the Welsh and the Men of the North, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-0465-6

- Dumville, David (1994), "The eastern terminus of the Antonine Wall: 12th or 13th century evidence" (PDF), Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland, 124: 293–298, retrieved 8 September 2011.

- Gelling, Margaret; W. F. H. Nicolaisen; Melville Richards (1970). The Names of Towns and Cities in Britain. Batsford. ISBN 0-7134-5235-8.

- Jackson, Kenneth H. (1969), The Gododdin: The Oldest Scottish Poem, Edinburgh University Press, pp. 77–78, ISBN 9780852240496

- Williams, Ifor (1972), The Beginnings of Welsh Poetry: Studies, University of Wales Press, ISBN 0-7083-0035-9

- Room, Adrian (2006). Placenames of the World. McFarland. ISBN 0-7864-2248-3. Retrieved 12 August 2011.