Epidural administration

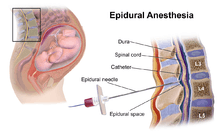

Epidural administration (from Ancient Greek ἐπί, "on, upon" + dura mater) is a medical route of administration in which a drug such as epidural analgesia and epidural anaesthesia or contrast agent is injected into the epidural space around the spinal cord. The epidural route is frequently employed by certain physicians and nurse anaesthetists to administer local anaesthetic agents, and occasionally to administer diagnostic (e.g. radiocontrast agents) and therapeutic (e.g., glucocorticoids) chemical substances. Epidural techniques frequently involve injection of drugs through a catheter placed into the epidural space. The injection can result in a loss of sensation—including the sensation of pain—by blocking the transmission of signals through nerve fibres in or near the spinal cord.

| Epidural administration | |

|---|---|

A freshly inserted lumbar epidural catheter. The site has been prepared with tincture of iodine, and the dressing has not yet been applied. Depth markings may be seen along the shaft of the catheter. | |

| ICD-9-CM | 03.90 |

| MeSH | D000767 |

| OPS-301 code | 8-910 |

The technique of epidural anaesthesia was first developed in 1921 by Spanish military surgeon Fidel Pagés (1886–1923).[1]

Difference from spinal anaesthesia

Spinal anaesthesia is a technique whereby a local anaesthetic drug is injected into the cerebrospinal fluid. This technique has some similarity to epidural anaesthesia, and lay people often confuse the two techniques. Important differences include:

- To achieve epidural analgesia or anaesthesia, a larger dose of drug is typically necessary than with spinal analgesia or anaesthesia.

- The onset of analgesia is slower with epidural analgesia or anaesthesia than with spinal analgesia or anaesthesia, which also confers a more gradual decrease in blood pressure.

- An epidural injection may be performed anywhere along the vertebral column (cervical, thoracic, lumbar, or sacral), while spinal injections are more often performed below the second lumbar vertebral body to avoid piercing and consequently damaging the spinal cord.

- It is easier to achieve segmental analgesia or anaesthesia using the epidural route than using the spinal route.

- An indwelling catheter is more commonly placed in the setting of epidural analgesia or anaesthesia than with spinal analgesia or anaesthesia.

- Epidural medication administration can be continued post-operatively (and re-dosed intraoperatively) via a catheter, while spinal anesthesia is generally a single shot injection.

Indications

Injecting medication into the epidural space is primarily performed for analgesia. This may be performed using a number of different techniques and for a variety of reasons. Additionally, some of the side-effects of epidural analgesia may be beneficial in some circumstances (e.g., vasodilation may be beneficial if the subject has peripheral vascular disease). When a catheter is placed into the epidural space (see below) a continuous infusion can be maintained for several days, if needed. Epidural analgesia may be used:

- For analgesia alone, where surgery is not contemplated. An epidural injection or infusion for pain relief (e.g. in childbirth) is less likely to cause loss of muscle power, but can subsequently be conveniently augmented to be sufficient for surgery, if needed.

- As an adjunct to general anaesthesia. The anaesthetist may use epidural analgesia in addition to general anaesthesia. This may reduce the patient's requirement for opioid analgesics. This is suitable for a wide variety of surgery, for example gynaecological surgery (e.g. hysterectomy), orthopaedic surgery (e.g. hip replacement), general surgery (e.g. laparotomy) and vascular surgery (e.g. open aortic aneurysm repair).

- As a sole technique for surgical anaesthesia. Some operations, most frequently Caesarean section, may be performed using an epidural anaesthetic as the sole technique. This can allow the patient to remain awake during the operation. The dose required for anaesthesia is much higher than that required for analgesia.

- For post-operative analgesia, whether the epidural was employed as the sole anaesthetic, or in conjunction with general anaesthesia, during the operation. Analgesics are administered into the epidural space typically for a few days after surgery, provided a catheter has been inserted. Through the use of a patient-controlled epidural analgesia (PCEA) infusion pump, a patient can supplement an epidural infusion with occasional supplemental doses of the infused medication through the epidural catheter.

- For the treatment of back pain. Injection of analgesics and steroids into the epidural space may improve some forms of back pain. See below.

- For the treatment of chronic pain or palliation of symptoms in terminal care, usually in the short- or medium-term.

The epidural space is more difficult and risky to access as one ascends the spine (because the spinal cord gains more nerves as it ascends and fills the epidural space leaving less room for error), so epidural techniques are most suitable for analgesia anywhere in the lower body and as high as the chest. They are (usually) much less suitable for analgesia for the neck, or arms and are not possible for the head (since sensory innervation for the head arises directly from the brain via cranial nerves rather than from the spinal cord via the epidural space.)

Contraindications

While the use of epidural analgesia and anesthetic is considered safe and effective, there are some contraindications to the use of such procedures.

Absolute contraindications include:[2]

- patient refusal

- safety concerns including inadequate equipment, experience, or appropriate supervision

- severe hematologic coagulopathy

- infection near the site of injection

Relative contraindications include:[2]

- low platelets without abnormal bleeding

- progressive neurologic disease (as neuraxial analgesia may further disease progression)

- increased ICP (due to possibility of dural puncture, CSF leakage, and consequent pressure on the brainstem)

- decreased but stable cardiac output (e.g. aortic stenosis)

- hypovolemia (as neuraxial analgesia decreases systemic vascular resistance)

- remote infection distant to injection site

Side effects

In addition to blocking the nerves which carry pain, local anaesthetic drugs in the epidural space will block other types of nerves as well, in a dose-dependent manner. Depending on the drug and dose used, the effects may last only a few minutes or up to several hours. Epidural analgesia typically involves using the opiates fentanyl or sufentanil, with bupivacaine or one of its congeners. Fentanyl is a powerful opioid with a potency 80 times that of morphine and side effects common to the opiate class. Sufentanil is another opiate, 5 to 10 times more potent than Fentanyl. Bupivacaine is markedly toxic if inadvertently given intravenously, causing excitation, nervousness, tingling around the mouth, tinnitus, tremor, dizziness, blurred vision, or seizures, followed by central nervous system depression: drowsiness, loss of consciousness, respiratory depression and apnea. Bupivacaine has caused several deaths by cardiac arrest when epidural anaesthetic has been accidentally inserted into a vein instead of the epidural space.[3][4]

Sensory nerve fibers are more sensitive to the effects of the local anaesthetics than motor nerve fibers.[5] This means that an epidural can provide analgesia while affecting muscle strength to a lesser extent. For example, a labouring woman may have a continuous epidural during labour that provides good analgesia without impairing her ability to move. If she requires a Caesarean section, she may be given a larger dose of epidural local anaesthetic.

The larger the dose used, the more likely it is that side effects will be evident.[6] For example, very large doses of epidural anaesthetic can cause paralysis of the intercostal muscles and thoracic diaphragm (which are responsible for breathing), and loss of sympathetic nerve input to the heart, which may cause a significant decrease in heart rate and blood pressure.[6] This may require emergency intervention, which may include support of the airway and the cardiovascular system.

The sensation of needing to urinate is often significantly diminished or even abolished after administration of epidural local anaesthetics and/or opioids.[7] Because of this, a urinary catheter is often placed for the duration of the epidural infusion.[7] People with continuous epidural infusions of local anaesthetic solutions typically ambulate only with assistance, if at all, in order to reduce the likelihood of injury due to a fall.

Large doses of epidurally administered opioids may cause troublesome itching, and respiratory depression.[8][9][10][11]

Complications

These include:

- failure to achieve analgesia or anaesthesia occurs in about 5% of cases, while another 15% experience only partial analgesia or anaesthesia. If analgesia is inadequate, another epidural may be attempted.

- The following factors are associated with failure to achieve epidural analgesia/anaesthesia:[12]

- Obesity

- Having given birth multiple times before

- History of a previous failure of epidural anaesthesia

- History of regular opiate use

- Cervical dilation of more than 7 cm at insertion

- The use of air to find the epidural space while inserting the epidural instead of alternatives such as saline or lidocaine

- The following factors are associated with failure to achieve epidural analgesia/anaesthesia:[12]

- Accidental dural puncture with headache (common, about 1 in 100 insertions[13][14][15]). The epidural space in the adult lumbar spine is only 3-5mm thick, which means it is comparatively easy to traverse it and accidentally puncture the dura (and arachnoid) with the needle. This may cause cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) to leak out into the epidural space, which may in turn cause a post dural puncture headache (PDPH). This can be severe and last several days, and in some rare cases weeks or months. It is caused by a reduction in CSF pressure and is characterised by postural exacerbation when the subject raises his/her head above the lying position. Mild PDPH may respond to caffeine and gabapentin administration.[16] If severe it may be successfully treated with an epidural blood patch (a small amount of the subject's own blood given into the epidural space via another epidural needle which clots and seals the leak). Most cases resolve spontaneously with time. A change in headache pattern (e.g., headache worse when the subject lies down) should alert the physician to the possibility of development of rare but dangerous complications, such as subdural hematoma or cerebral venous thrombosis.[17]

- Delayed onset of breastfeeding and shorter duration of breastfeeding: In a study looking at breastfeeding 2 days after epidural anaesthesia, epidural analgesia in combination with oxytocin infusion caused women to have significantly lower oxytocin and prolactin levels in response to the baby breastfeeding on day 2 postpartum, which means less milk is produced. In many women undergoing epidural analgesia during labour oxytocin is used to augment uterine contractions.[18]

- Bloody tap (occurs in about 1 in 30–50).[19] Epidural veins can be inadvertently punctured with the needle during the procedure. This is a common occurrence and is not usually considered a complication. In people who have normal blood clotting, permanent neurological problems are extremely rare (estimated less than 0.07%).[20] However, people who have a coagulopathy may be at risk of epidural hematoma.

- People with thrombocytopenia might suffer from a bleed. A Cochrane review was conducted by comparing retrospective trials in 2018 to determine the effect of platelet transfusions prior to a lumbar puncture or epidural anaesthesia for participants that suffer from thrombocytopenia.[21] When comparing a platelet transfusion with no platelet transfusion, the evidence is very uncertain about the effect of platelet transfusions prior to lumbar puncture on major surgery-related bleeding within 24 hours and the surgery-related complications up to 7 days after the procedure.[21]

- Catheter placed into a vein (uncommon, less than 1 in 300). Occasionally the catheter may be inadvertently placed into an epidural vein, which results in all the anaesthetic being injected intravenously, where it can cause seizures or cardiac arrest[22][23] in large doses (about 1 in 10,000 insertions[15]). Proper epidural technique includes beginning with a "test dose" of a more benign medication (e.g.lidocaine with epinephrine) that can elicit symptoms of inadvertent venous administration (tachycardia, tinnitus) before administration of the more cardiotoxic local anesthetics to mitigate against this occurrence.

- High block, as described above (uncommon, less than 1 in 500).

- Catheter misplaced into the subarachnoid space (rare, less than 1 in 1000). If the catheter is accidentally misplaced into the subarachnoid space (e.g. after an unrecognised accidental dural puncture), normally cerebrospinal fluid can be freely aspirated from the catheter (which would usually prompt the anaesthetist to withdraw the catheter and resite it elsewhere), though occasionally no fluid is aspirated despite a dural puncture.[24]

- If dural puncture is not recognised, large doses of anaesthetic may be delivered directly into the cerebrospinal fluid. This may result in a high block, or, more rarely, a total spinal, where anaesthetic is delivered directly to the brainstem, causing unconsciousness and sometimes seizures.

- Neurological injury lasting less than 1 year (rare, about 1 in 6,700).[25]

- Epidural abscess formation (very rare, about 1 in 145,000).[25] Infection risk increases with the duration catheters are left in place, although infection was still uncommon after an average of 3 to 5 days' duration.[26]

- Epidural haematoma formation (very rare, about 1 in 168,000).[25]

- Neurological injury lasting longer than 1 year (extremely rare, about 1 in 240,000).[25]

- Paraplegia (1 in 250,000).[27]

- Arachnoiditis is a rare and devastating complication of epidural injection, with many purported causative agents[28] that requires management by a pain specialist.

- Death (extremely rare, less than 1 in 100,000).[27]

The figures above relate to epidural anaesthesia and analgesia in healthy individuals.

Evidence to support the assertion that epidural analgesia increases the risk of anastomotic breakdown following bowel surgery is lacking.[29][30]

Controversial claims:

- "epidural anaesthesia and analgesia significantly slows the second stage of labour". The following are a few plausible hypotheses for this phenomenon:

- The release of oxytocin, which stimulates the uterine contractions that are needed to move the child out through the vagina, may be decreased with epidural anaesthesia or analgesia due to factors involving the reduction of stress, such as:

- Epidural analgesia may reduce the endocrine stress response to pain[31]

- Diminished release of epinephrine from the adrenal medulla slows the release of oxytocin[32]

- Diminished blood pressure, accommodated by both decreased stress and less adrenal release, may decrease the release of oxytocin as a natural mechanism to avoid hypotension.[33] It may also affect the heart-rate of the fetus.[34]

- Epidural analgesia may reduce the endocrine stress response to pain[31]

- The release of oxytocin, which stimulates the uterine contractions that are needed to move the child out through the vagina, may be decreased with epidural anaesthesia or analgesia due to factors involving the reduction of stress, such as:

- Still plausible (though less studied without a documented reproduction in a laboratory setting) are the effects of the reclined position of the woman on the fetus, both immediately prior to and during delivery.

- These hypotheses generally posit an interaction with the force of gravity on fetal position and movement, as demonstrated by the following examples:

- Transverse or posterior fetal positioning may become more likely as a result of the shift in orientation to gravitational force.

- Diminished gravitational assistance is present in building pressure for commencing delivery and for progressing the fetus along the vagina.

- It is important to note that the orientation of the fetus can be established by ultrasonic sonography prior to, during, and after the administration of an epidural block. This would seem a fine experiment for testing the first hypothesis. It should also be noted that the majority of fetal movement through the vagina is accomplished by cervical contractions, and so the role of gravity and its force relative to the position of the woman in labour (on delivery, not development) is difficult to establish.

- These hypotheses generally posit an interaction with the force of gravity on fetal position and movement, as demonstrated by the following examples:

- There has been a good deal of concern, based on older observational studies, that women who have epidural analgesia during labour are more likely to require a cesarean delivery.[35] However, the preponderance of evidence now supports the conclusion that the use of epidural analgesia during labour does not have a significant effect on rates of cesarean delivery. A Cochrane review analysis of over 11,000 women confirmed there was no increase in the rate of Caesarean delivery when epidural analgesia was employed.[36]

Epidural analgesia does increase the duration of the second stage of labour by 15 to 30 minutes and may increase the rate of instrument-assisted vaginal deliveries as well as that of oxytocin administration.[37][38] Some people have also been concerned about whether the use of epidural analgesia in early labour increases the risk of cesarean delivery. Three randomized, controlled trials showed that early initiation of epidural analgesia (cervical dilatation, <4 cm) does not increase the rate of cesarean delivery among women with spontaneous or induced labour, as compared with early initiation of analgesia with parenteral opioids.[39][40][41]

Anatomy

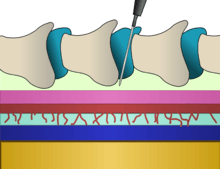

The epidural space is the space inside the bony spinal canal but just outside the dura mater ("dura"). In contact with the inner surface of the dura is another membrane called the arachnoid mater ("arachnoid"). The cerebrospinal fluid that surrounds the spinal cord is contained by the arachnoid mater. In adults, the spinal cord terminates around the level of the disc between L1 and L2 (in neonates it extends to L3 but can reach as low as L4), below which lies a bundle of nerves known as the cauda equina ("horse's tail"). Hence, lumbar epidural injections carry a low risk of injuring the spinal cord.

Insertion of an epidural needle involves threading a needle between the bones, through the ligaments and into the epidural potential space taking great care to avoid puncturing the layer immediately below containing CSF under pressure.

Technique

Procedures involving injection of any substance into the epidural space require the operator to be technically proficient in order to avoid complications. Proficiency can be gained using bananas or other fruits as a model.[42] [43] The subject may be in the seated, lateral or prone positions.[44] The level of the spine at which the catheter is best placed depends mainly on the site and type of an intended operation or the anatomical origin of pain. The iliac crest is a commonly used anatomical landmark for lumbar epidural injections, as this level roughly corresponds with the fourth lumbar vertebra, which is usually well below the termination of the spinal cord. The Tuohy needle, designed with a 90-degree curved tip and sidehole to redirect the inserted catheter vertically along the axis of the spine, is usually inserted in the midline, between the spinous processes. When using a paramedian approach, the tip of the needle passes along a shelf of vertebral bone called the lamina until just before reaching the ligamentum flavum and the epidural space.

Some studies have noted faster catheter insertion time in a paramedian approach compared to midline. There is also evidence of lower incidence of paresthesia with the paramedian group. However, the paramedian approach is more painful and requires more local anesthetic due to the needle traversing sensitive structures such as the paraspinous muscles.[45]

Along with a sudden loss of resistance to pressure on the plunger of the syringe, a slight clicking sensation may be felt by the operator as the tip of the needle breaches the ligamentum flavum and enters the epidural space. Practitioners commonly use air or saline for identifying the epidural space. However, whilst evidence was accumulating that saline is preferable to air, as it was thought to be associated with a better quality of analgesia and lower incidence of post-dural-puncture headache,[45][46] A systematic review in 2014 showed no difference in terms of ability to identify the epidural space or safety.[47] In addition to the loss of resistance technique, realtime observation of the advancing needle is becoming more common. This may be done using a portable ultrasound scanner, or with fluoroscopy (moving X-ray pictures).[48]

After placement of the tip of the needle into the epidural space, a catheter is often threaded through the needle. The needle is then withdrawn over the catheter. Generally the catheter is inserted 4–6 cm into the epidural space.[49] The catheter is typically secured to the skin with adhesive tape or dressings to prevent it becoming dislodged.

The catheter is a fine plastic tube, through which anaesthetics may be injected into the epidural space. Many epidural catheters have a blind end, and three or more orifices along the shaft near the distal tip (far end) of the catheter. This not only disperses the injected agents over more spinal levels, but also reduces the incidence of catheter blockage.

Choice of agents A person receiving an epidural for pain relief may receive local anaesthetic, an opioid, or both. Common local anaesthetics include lidocaine, mepivacaine, bupivacaine, ropivacaine, and chloroprocaine. Common opioids include hydromorphone, morphine, fentanyl, sufentanil, and pethidine (known as meperidine in the United States). These are injected in relatively small doses, compared to when they are injected intravenously. Other agents such as clonidine or ketamine are also sometimes used.

Bolus or infusion?

For a short procedure, the anaesthetist may introduce a single dose of medication (the "bolus" technique). This will eventually dissipate. Thereafter, the anaesthetist may repeat the bolus provided the catheter remains undisturbed. For a prolonged effect, a continuous infusion of drugs may be employed. There is some evidence that an automated intermittent bolus technique provides better analgesia than a continuous infusion technique, though the total doses are identical.[50][51][52]

Level and intensity of block Typically, the effects of the epidural block are noted below a specific level on the body. This level may be determined by the anaesthetist. A high insertion level may result in sparing of nerve function in the lower spinal nerves. For example, a thoracic epidural may be performed for upper abdominal surgery, but may not have any effect on the perineum (area around the genitals) or pelvic organs.[53] Nonetheless, giving very large volumes into the epidural space may spread the block both higher and lower.

The intensity of the block is determined by the concentration of local anaesthetic solution used. For example, 0.1% bupivacaine may provide adequate analgesia for a woman in labour, but would likely be insufficient for surgical anaesthesia. Conversely, 0.5% bupivacaine would provide a more intense block, likely sufficient for surgery.

Removing the catheter

The catheter is usually removed when the subject is able to take oral pain medications. Catheters can safely remain in place for several days with little risk of bacterial infection,[54][55][56] particularly if the skin is prepared with a chlorhexidine solution.[57] Subcutaneously tunneled epidural catheters may be left in place for longer periods, with a low risk of infection or other complications.[58][59][60]

Special situations

Epidural analgesia during childbirth

Epidural analgesia provides rapid pain relief in most cases. It is more effective than opioids and other common modalities of analgesia in childbirth.[36] Epidurals during childbirth are the most commonly used anesthesia in this situation. The medication concentrations and doses are kept low to decrease the side effects to both mother and baby. When in labor the mother does not usually feel pain after an epidural but they do still feel the pressure. Women are able to bear down and push with contractions.[61] Epidural clonidine is rarely used but has been extensively studied for management of analgesia during labor.[62] Epidural analgesia is a relatively safe method of relieving pain in labor. In a 2018 Cochrane review which included 52 randomized controlled studies involving more than 11,000 women, where most studies compared epidural analgesia with opiates, epidural analgesia in childbirth was associated with the following advantages and disadvantages:[36]

| Advantages | Disadvantages |

|---|---|

|

|

However, the review found no difference in overall Caesarean delivery rates, nor were there effects on the baby soon after birth. Also, the occurrence of long-term backache was no different whether an epidural was or was not used.[36]

Though complications are rare, some women and their babies will experience them. Some side effects for the mother include headaches, dizziness, difficulty breathing and seizures. The child may experience slowed heartbeat, temperature regulation issues and there could be high levels of drugs in the child's system from the epidural.[64]

Differing outcomes in frequency of Cesarean section may be explained by differing institutions or their practitioners: epidural anesthesia and analgesia administered at top-rated institutions does not generally result in a clinically significant increase in caesarean rates, whereas the risk of caesarean delivery at poorly ranked facilities seems to increase with the use of epidural.[65]

Regarding early or late administration of epidural analgesia, there is no overall difference in outcomes for first-time mothers in labor.[66] Specifically, the rates of caesarean section, instrumental birth, and duration of labor are equal, as are baby Apgar scores and cord pH.[66]

Epidurals (other than low-dose ambulatory epidurals[67]) preclude maternal movement, but "walking, movement, and changing positions during labor help labor progress, enhance comfort, and decrease the risk of complications."[68]

One study concluded that women whose epidural infusions contained fentanyl were less likely to fully breastfeed their infant in the few days after birth and more likely to stop breastfeeding in the first 24 weeks.[69] However, this study has been criticized for several reasons, one of which is that the original patient records were not examined in this study, and so many of the epidural infusions were assumed to contain fentanyl when almost certainly they would not have.[70] In addition, all those who had received epidural infusions in this study had also received systemic pethidine, which would be much more likely to be the cause of any effect on breastfeeding due to the higher amounts of medication used via that route. If this were the case, then early epidural analgesia which avoided the need for pethidine would be expected to improve breastfeeding outcomes rather than worsen them. Traditional epidural for labor relieves pain reliably only during first stage of labor (uterine contractions until cervix is fully open). It does not relieve pain as reliably during the second stage of labor (passage of the fetus through the vagina).

Epidural analgesia after surgery

Epidural analgesia has been demonstrated to have several benefits after surgery, including:

- It provides effective analgesia without the need for systemic opioids.[71]

- The incidence of postoperative respiratory problems and chest infections is reduced.[72]

- The incidence of postoperative myocardial infarction ("heart attack") is reduced.[73][74]

- The stress response to surgery is reduced.[73][75]

- Motility of the intestines is improved by blockade of the sympathetic nervous system.[73][29]

- Use of epidural analgesia during surgery reduces blood transfusion requirements.[73]

Despite these benefits, no survival benefit has been proven for high-risk individuals.[76]

Caudal epidural analgesia

The caudal approach to the epidural space involves the use of a Tuohy needle, an intravenous catheter, or a hypodermic needle to puncture the sacrococcygeal membrane. Injecting local anaesthetic at this level can result in analgesia and/or anaesthesia of the perineum and groin areas. The caudal epidural technique is often used in infants and children undergoing surgery involving the groin, pelvis or lower extremities. In this population, caudal epidural analgesia is usually combined with general anaesthesia since most children do not tolerate surgery when regional anaesthesia is employed as the sole modality.

Combined spinal-epidural techniques

For some procedures, the anaesthetist may choose to combine the rapid onset and reliable, dense block of a spinal anaesthetic with the post-operative analgesic effects of an epidural. This is called combined spinal and epidural anaesthesia (CSE). The practitioner may insert the spinal anaesthetic at one level, and the epidural at an adjacent level. Alternatively, after locating the epidural space with the Tuohy needle, a spinal needle may be inserted through the Tuohy needle into the subarachnoid space. The spinal dose is then given, the spinal needle withdrawn, and the epidural catheter inserted as normal. This method, known as the "needle-through-needle" technique, may be associated with a slightly higher risk of placing the catheter into the subarachnoid space.

Epidural steroid injection

Epidural steroid injection may be used to treat radiculopathy, radicular pain and inflammation caused by such conditions as spinal disc herniation, degenerative disc disease, and spinal stenosis. Steroids may be injected at the cervical, thoracic, lumbar, or caudal/sacral levels, depending on the specific area where the pathology (disease, condition, or injury) is located.

Epidural blood patch

Epidural blood patch may be used to treat Post-dural-puncture headache, leakage of cerebrospinal fluid due to accidental dural puncture occurring in approximately 1.5% of epidural neuraxial procedures.[2] A small amount of the patient's own blood is injected into the epidural space, clotting and closing the site of puncture.[77] Another theory proposes that the injection of blood counteracts the decrease in cerebrospinal fluid from the puncture.

History

In 1885, American neurologist James Leonard Corning (1855–1923), of Acorn Hall in Morristown, NJ, was the first to perform a neuraxial blockade, when he injected 111 mg of cocaine into the epidural space of a healthy male volunteer[78] (although at the time he believed he was injecting it into the subarachnoid space).[79]

In 1901, Fernand Cathelin (1873-1929) first reported blocking the lowest sacral and coccygeal nerves through the epidural space by injecting local anesthetic through the sacral hiatus.[2]

In 1921, Spanish military surgeon Fidel Pagés (1886–1923) developed the technique of "single-shot" lumbar epidural anaesthesia,[1] which was later popularized by Italian surgeon Achille Mario Dogliotti (1897–1966).[80]

In 1931, Romanian Eugen Bogdan Aburel described the technique for placement of a continuous epidural catheter for pain relief during childbirth.[81][82]

In 1933, Italian Achile Mario Dogliotti (1897-1966) described the loss of resistance technique, and Argentinian Alberto Gutiérrez described the hanging drop technique, both to identify when the epidural space has been entered.[82][2]

In 1941, Americans Robert Andrew Hingson (1913–1996) and Waldo B. Edwards popularized the technique of continuous caudal anaesthesia using an indwelling needle.[83] The first successful use of a flexible catheter for continuous caudal anaesthesia in a labouring woman was described in 1942.[84]

In 1947, Cuban Manuel Martínez Curbelo (1906–1962) was the first to describe placement of a lumbar epidural catheter.[85]

In 1979, M. Behar reported the first use of epidural catheter narcotics.[86]

References

- Pagés, F (1921). "Anestesia metamérica". Revista de Sanidad Militar (in Spanish). 11: 351–4.

- Silva M, Halpern SH (2010). "Epidural analgesia for labor: Current techniques". Local and Regional Anesthesia. 3: 143–53. doi:10.2147/LRA.S10237. PMC 3417963. PMID 23144567.

- Rosenblatt MA, Abel M, Fischer GW, Itzkovich CJ, Eisenkraft JB (2006). "Successful Use of a 20% Lipid Emulsion to Resuscitate a Patient after a Presumed Bupivacaine-related Cardiac Arrest". Anesthesiology. 105 (7): 217–8. doi:10.1097/00000542-200607000-00033. PMID 16810015. S2CID 40214528.

- Mulroy MF (2002). "Systemic toxicity and cardiotoxicity from local anesthetics: incidence and preventive measures". Reg Anesth Pain Med. 27 (6): 556–61. doi:10.1053/rapm.2002.37127. PMID 12430104.

- Stark P (February 1979). "The effect of local anaesthetic agents on afferent and motor nerve impulses in the frog". Archives Internationales de Pharmacodynamie et de Therapie. 237 (2): 255–66. PMID 485692.

- Tobias JD, Leder M (October 2011). "Procedural sedation: A review of sedative agents, monitoring, and management of complications". Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia. 5 (4): 395–410. doi:10.4103/1658-354X.87270. PMC 3227310. PMID 22144928.

- Baldini G, Bagry H, Aprikian A, Carli F (May 2009). "Postoperative urinary retention: anesthetic and perioperative considerations". Anesthesiology. 110 (5): 1139–57. doi:10.1097/ALN.0b013e31819f7aea. PMID 19352147.

- Krane EJ, Tyler DC, Jacobson LE (1989). "The dose response of caudal morphine in children". Anesthesiology. 71 (1): 48–52. doi:10.1097/00000542-198907000-00009. PMID 2751139.

- Jacobson L, Chabal C, Brody MC (1988). "A dose-response study of intrathecal morphine: efficacy, duration, optimal dose, and side effects". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 67 (11): 1082–8. doi:10.1213/00000539-198867110-00011. PMID 3189898.

- Wüst HJ, Bromage PR (1987). "Delayed respiratory arrest after epidural hydromorphone". Anaesthesia. 42 (4): 404–6. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1987.tb03982.x. PMID 2438964.

- Haberkern CM, Lynn AM, Geiduschek JM, Nespeca MK, Jacobson LE, Bratton SL, Pomietto M (1996). "Epidural and intravenous bolus morphine for postoperative analgesia in infants". Can J Anaesth. 43 (12): 1203–10. doi:10.1007/BF03013425. PMID 8955967.

- Agaram R, Douglas MJ, McTaggart RA, Gunka V (January 2009). "Inadequate pain relief with labor epidurals: a multivariate analysis of associated factors". Int J Obstet Anesth. 18 (1): 10–4. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.10.008. PMID 19046867.

- Norris MC, Leighton BL, DeSimone CA (1989). "Needle bevel direction and headache after inadvertent dural puncture". Anesthesiology. 70 (5): 729–31. doi:10.1097/00000542-198905000-00002. PMID 2655500.

- Sprigge JS, Harper SJ (2008). "Accidental dural puncture and post dural puncture headache in obstetric anaesthesia: presentation and management: a 23-year survey in a district general hospital". Anaesthesia. 63 (1): 36–43. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.2007.05285.x. PMID 18086069.

- Wilson IH, Allman KG (2006). Oxford handbook of anaesthesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 20. ISBN 978-0-19-856609-0.

- Basurto, Ona (July 15, 2015). "Drugs for treating headache after a lumbar puncture". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. The Cochrane Library (7): CD007887. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007887.pub3. PMC 6457875. PMID 26176166. Retrieved November 16, 2018.

Caffeine proved to be effective in decreasing the number of people with PDPH and those requiring extra drugs (2 or 3 in 10 with caffeine compared to 9 in 10 with placebo). Gabapentin, theophylline and hydrocortisone also proved to be effective, relieving pain better than placebo

- Wang Y, Wang S (March 10, 1994). "Headache associated with low CSF pressure". MedLink.

- Jonas K, Johansson LM, Nissen E, Ejdebäck M, Ransjö-Arvidson AB, Uvnäs-Moberg K (2009). "Effects of Intrapartum Oxytocin Administration and Epidural Analgesia on the Concentration of Plasma Oxytocin and Prolactin, in Response to Suckling During the Second Day Postpartum". Breastfeed Med. 4 (2): 71–82. doi:10.1089/bfm.2008.0002. PMID 19210132.

- Shih CK, Wang FY, Shieh CF, Huang JM, Lu IC, Wu LC, Lu DV (2012). "Soft catheters reduce the risk of intravascular cannulation during epidural block—a retrospective analysis of 1,117 cases in a medical center". Kaohsiung J. Med. Sci. 28 (7): 373–6. doi:10.1016/j.kjms.2012.02.004. PMID 22726899.

- Giebler RM, Scherer RU, Peters J (1997). "Incidence of neurologic complications related to thoracic epidural catheterization". Anesthesiology. 86 (1): 55–63. doi:10.1097/00000542-199701000-00009. PMID 9009940.

- Estcourt, Lise J; Malouf, Reem; Hopewell, Sally; Doree, Carolyn; Van Veen, Joost (April 30, 2018). Cochrane Haematological Malignancies Group (ed.). "Use of platelet transfusions prior to lumbar punctures or epidural anaesthesia for the prevention of complications in people with thrombocytopenia". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD011980.pub3.

- Clarkson CW, Hondeghem LM (1985). "Mechanism for bupivacaine depression of cardiac conduction: fast block of sodium channels during the action potential with slow recovery from block during diastole". Anesthesiology. 62 (4): 396–405. doi:10.1097/00000542-198504000-00006. PMID 2580463.

- Groban L, Deal DD, Vernon JC, James RL, Butterworth J (2001). "Cardiac resuscitation after incremental overdosage with lidocaine, bupivacaine, levobupivacaine, and ropivacaine in anesthetized dogs". Anesth Analg. 92 (1): 37–43. doi:10.1097/00000539-200101000-00008. PMID 11133597.

- Troop M. (2002). "Negative aspiration for cerebral fluid does not assure proper placement of epidural catheter". AANA J. 60 (3): 301–3. PMID 1632158.

- "Epidurals and risk: it all depends [May 2007; 159–3]". Archived from the original on December 23, 2012.

- Scott DA, Beilby DS, McClymont C (1995). "Postoperative analgesia using epidural infusions of fentanyl with bupivacaine. A prospective analysis of 1,014 patients". Anesthesiology. 83 (4): 727–37. doi:10.1097/00000542-199510000-00012. PMID 7574052.

- Wilson IH, Allman KG (2006). Oxford handbook of anaesthesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 21. ISBN 978-0-19-856609-0.

- Rice I, Wee MY, Thomson K (January 2004). "Obstetric epidurals and chronic adhesive arachnoiditis". Br J Anaesth. 92 (1): 109–20. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.532.6709. doi:10.1093/bja/aeh009. PMID 14665562.

- Gendall KA, Kennedy RR, Watson AJ, Frizelle FA (2007). "The effect of epidural analgesia on postoperative outcome after colorectal surgery". Colorectal Dis. 9 (7): 584–98, discussion 598–600. doi:10.1111/j.1463-1318.2007.1274.x. PMID 17506795.

- Wilson IH, Allman KG (2006). Oxford handbook of anaesthesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1039. ISBN 978-0-19-856609-0.

- Whitehead SA, Nussey S (2001). Endocrinology: an integrated approach. Oxford: BIOS. p. 122. ISBN 978-1-85996-252-7.

- Gregory M. "Endocrine System: Posterior Pituitary". Archived from the original on December 13, 2007. Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- Takayanagi Y, Yoshida M, Bielsky IF, Ross HE, Kawamata M, Onaka T, Yanagisawa T, Kimura T, Matzuk MM, Young LJ, Nishimori K (2005). "Pervasive social deficits, but normal parturition, in oxytocin receptor-deficient mice". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 102 (44): 16096–101. Bibcode:2005PNAS..10216096T. doi:10.1073/pnas.0505312102. PMC 1276060. PMID 16249339.

- Mayo Clinic Staff. "Labor and Delivery: Pain Medications – Epidural Block". Retrieved July 5, 2011.

- Seyb ST, Berka RJ, Socol ML, Dooley SL (1999). "Risk of cesarean delivery with elective induction of labour at term in nulliparous women". Obstet Gynecol. 94 (4): 600–607. doi:10.1016/S0029-7844(99)00377-4. PMID 10511367.

- Anim-Somuah M, Smyth RM, Cyna AM, Cuthbert A (2018). "Epidural versus non-epidural or no analgesia in labour". The Cochrane Library. 5: CD000331. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD000331.pub4. PMC 6494646. PMID 29781504.

- Liu EH, Sia AT (June 2004). "Rates of caesarean section and instrumental vaginal delivery in nulliparous women after low concentration epidural infusions or opioid analgesia: systematic review". BMJ. 328 (7453): 1410. doi:10.1136/bmj.38097.590810.7C. PMC 421779. PMID 15169744.

- Halpern SH, Muir H, Breen TW, Campbell DC, Barrett J, Liston R, Blanchard JW (November 2004). "A multicenter randomized controlled trial comparing patient-controlled epidural with intravenous analgesia for pain relief in labor". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 99 (5): 1532–8, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000136850.08972.07. PMID 15502060.

- Wong CA, Scavone BM, Peaceman AM, McCarthy RJ, Sullivan JT, Diaz NT, Yaghmour E, Marcus RJ, Sherwani SS, Sproviero MT, Yilmaz M, Patel R, Robles C, Grouper S (February 2005). "The risk of cesarean delivery with neuraxial analgesia given early versus late in labor". The New England Journal of Medicine. 352 (7): 655–65. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa042573. PMID 15716559. S2CID 6464066.

- Ohel G, Gonen R, Vaida S, Barak S, Gaitini L (March 2006). "Early versus late initiation of epidural analgesia in labor: does it increase the risk of cesarean section? A randomized trial". American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology. 194 (3): 600–5. doi:10.1016/j.ajog.2005.10.821. PMID 16522386.

- Wong CA, McCarthy RJ, Sullivan JT, Scavone BM, Gerber SE, Yaghmour EA (May 2009). "Early compared with late neuraxial analgesia in nulliparous labor induction: a randomized controlled trial". Obstetrics and Gynecology. 113 (5): 1066–74. doi:10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181a1a9a8. PMID 19384122.

- Raj D, Williamson RM, Young D, Russell D (2013). "A simple epidural simulator: a blinded study assessing the 'feel' of loss of resistance in four fruits". Eur J Anaesthesiol. 30 (7): 405–8. doi:10.1097/EJA.0b013e328361409c. PMID 23749185. S2CID 2647529.

- Leighton BL (1989). "A greengrocer's model of the epidural space". Anesthesiology. 70 (2): 368–9. doi:10.1097/00000542-198902000-00038. PMID 2913877.

- "Epidural Steroid Injections". Pain Management Specialists.

- Norman D (2003). "Epidural analgesia using loss of resistance with air versus saline: does it make a difference? Should we reevaluate our practice?". AANA Journal. 71 (6): 449–53. PMID 15098532.

- Beilin Y, Arnold I, Telfeyan C, Bernstein HH, Hossain S (2000). "Quality of analgesia when air versus saline is used for identification of the epidural space in the parturient". Reg Anesth Pain Med. 25 (6): 596–9. doi:10.1053/rapm.2000.9535. PMID 11097666.

- Antibas, Pedro L; do Nascimento Junior, Paulo; Braz, Leandro G; Vitor Pereira Doles, João; Módolo, Norma SP; El Dib, Regina (July 17, 2014). "Air versus saline in the loss of resistance technique for identification of the epidural space". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (7): CD008938. doi:10.1002/14651858.cd008938.pub2. ISSN 1465-1858. PMC 7167505. PMID 25033878.

- Rapp HJ, Folger A, Grau T (2005). "Ultrasound-guided epidural catheter insertion in children". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 101 (2): 333–9, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000156579.11254.D1. PMID 16037140. S2CID 17614330.

- Beilin Y, Bernstein HH, Zucker-Pinchoff B (1995). "The optimal distance that a multiorifice epidural catheter should be threaded into the epidural space". Anesth Analg. 81 (2): 301–4. doi:10.1097/00000539-199508000-00016. PMID 7618719.

- Lim Y, Sia AT, Ocampo C (2005). "Automated regular boluses for epidural analgesia: a comparison with continuous infusion". Int J Obstet Anesth. 14 (4): 305–9. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2005.05.004. PMID 16154735.

- Wong CA, Ratliff JT, Sullivan JT, Scavone BM, Toledo P, McCarthy RJ (2006). "A randomized comparison of programmed intermittent epidural bolus with continuous epidural infusion for labor analgesia". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 102 (3): 904–9. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000197778.57615.1a. PMID 16492849.

- Sia AT, Lim Y, Ocampo C (2007). "A comparison of a basal infusion with automated mandatory boluses in parturient-controlled epidural analgesia during labor". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 104 (3): 673–8. doi:10.1213/01.ane.0000253236.89376.60. PMID 17312228.

- Basse L, Werner M, Kehlet H (2000). "Is urinary drainage necessary during continuous epidural analgesia after colonic resection?". Reg Anesth Pain Med. 25 (5): 498–501. doi:10.1053/rapm.2000.9537. PMID 11009235.

- Kost-Byerly S, Tobin JR, Greenberg RS, Billett C, Zahurak M, Yaster M (1998). "Bacterial colonization and infection rate of continuous epidural catheters in children". Anesth Analg. 86 (4): 712–6. doi:10.1097/00000539-199804000-00007. PMID 9539589.

- Kostopanagiotou G, Kyroudi S, Panidis D, Relia P, Danalatos A, Smyrniotis V, Pourgiezi T, Kouskouni E, Voros D (2002). "Epidural catheter colonization is not associated with infection". Surgical Infections. 3 (4): 359–65. doi:10.1089/109629602762539571. PMID 12697082.

- Yuan HB, Zuo Z, Yu KW, Lin WM, Lee HC, Chan KH (2008). "Bacterial colonization of epidural catheters used for short-term postoperative analgesia: microbiological examination and risk factor analysis". Anesthesiology. 108 (1): 130–7. doi:10.1097/01.anes.0000296066.79547.f3. PMID 18156891.

- Kinirons B, Mimoz O, Lafendi L, Naas T, Meunier J, Nordmann P (2001). "Chlorhexidine versus povidone iodine in preventing colonization of continuous epidural catheters in children: a randomized, controlled trial". Anesthesiology. 94 (2): 239–44. doi:10.1097/00000542-200102000-00012. PMID 11176087. S2CID 20016232.

- Aram L, Krane EJ, Kozloski LJ, Yaster M (2001). "Tunneled epidural catheters for prolonged analgesia in pediatric patients". Anesth Analg. 92 (6): 1432–8. doi:10.1097/00000539-200106000-00016. PMID 11375820. S2CID 21017121.

- Bubeck J, Boos K, Krause H, Thies KC (2004). "Subcutaneous tunneling of caudal catheters reduces the rate of bacterial colonization to that of lumbar epidural catheters". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 99 (3): 689–93, table of contents. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000130023.48259.FB. PMID 15333395.

- Nitescu P, Sjöberg M, Appelgren L, Curelaru I (1995). "Complications of intrathecal opioids and bupivacaine in the treatment of "refractory" cancer pain". Clin J Pain. 11 (1): 45–62. doi:10.1097/00002508-199503000-00006. PMID 7540439.

- Buckley, Sarah (January 24, 2014). "Epidurals: risks and concerns for mother and baby". Midwifery Today with International Midwife. Mothering No.133 (81): 21–3, 63–6. PMID 17447690. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Patel SS, Dunn CJ, Bryson HM (1996). "Epidural clonidine: a review of its pharmacology and efficacy in the management of pain during labour and postoperative and intractable pain". CNS Drugs. 6 (6): 474–497. doi:10.2165/00023210-199606060-00007. S2CID 72544106.

- Salem IC, Fukushima FB, Nakamura G, Ferrari F, Navarro LC, Castiglia YM, Ganem EM (2007). "Side effects of subarachnoid and epidural sufentanil associated with a local anesthetic in patients undergoing labor analgesia". Revista Brasileira de Anestesiologia. 57 (2): 125–135. doi:10.1590/s0034-70942007000200001. PMID 19466346.

- "Anesthesia". Harvard University Press. Retrieved April 18, 2014.

- Thorp JA, Breedlove G (1996). "Epidural analgesia in labor: an evaluation of risks and benefits". Birth. 23 (2): 63–83. doi:10.1111/j.1523-536X.1996.tb00833.x. PMID 8826170.

- Sng BL, Leong WL, Zeng Y, Siddiqui FJ, Assam PN, Lim Y, Chan ES, Sia AT (October 9, 2014). "Early versus late initiation of epidural analgesia for labour". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 10 (10): CD007238. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD007238.pub2. PMID 25300169.

- Dr Hayley Willacy; Dr Colin Tidy (June 16, 2014). "Pain relief in labour". Patient.info. EMIS. Retrieved September 2, 2014.

- Lothian JA (2009). "Safe, healthy birth: what every pregnant woman needs to know". J Perinat Educ. 18 (3): 48–54. doi:10.1624/105812409X461225. PMC 2730905. PMID 19750214.

- Torvaldsen S, Roberts CL, Simpson JM, Thompson JF, Ellwood DA (2006). "Intrapartum epidural analgesia and breastfeeding: a prospective cohort study". International Breastfeeding Journal. 1 (1): 24. doi:10.1186/1746-4358-1-24. PMC 1702531. PMID 17134489.

- Camann W (2007). "Labor analgesia and breast feeding: avoid parenteral narcotics and provide lactation support". Int J Obstet Anesth. 16 (3): 199–201. doi:10.1016/j.ijoa.2007.03.008. PMID 17521903.

- Block BM, Liu SS, Rowlingson AJ, Cowan AR, Cowan JA, Wu CL (2003). "Efficacy of postoperative epidural analgesia: a meta-analysis". JAMA. 290 (18): 2455–63. doi:10.1001/jama.290.18.2455. PMID 14612482. S2CID 35260733.

- Ballantyne JC, Carr DB, deFerranti S, Suarez T, Lau J, Chalmers TC, Angelillo IF, Mosteller F (1998). "The comparative effects of postoperative analgesic therapies on pulmonary outcome: cumulative meta-analyses of randomized, controlled trials". Anesth Analg. 86 (3): 598–612. doi:10.1097/00000539-199803000-00032. PMID 9495424. S2CID 37136047.

- Wilson IH, Allman KG (2006). Oxford handbook of anaesthesia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. p. 1038. ISBN 978-0-19-856609-0.

- Beattie WS, Badner NH, Choi P (2001). "Epidural analgesia reduces postoperative myocardial infarction: a meta-analysis". Anesth Analg. 93 (4): 853–8. doi:10.1097/00000539-200110000-00010. PMID 11574345. S2CID 9449275.

- Yokoyama M, Itano Y, Katayama H, Morimatsu H, Takeda Y, Takahashi T, Nagano O, Morita K (2005). "The effects of continuous epidural anesthesia and analgesia on stress response and immune function in patients undergoing radical esophagectomy". Anesthesia & Analgesia. 101 (5): 1521–7. doi:10.1213/01.ANE.0000184287.15086.1E. PMID 16244024.

- Rigg JR, Jamrozik K, Myles PS, Silbert BS, Peyton PJ, Parsons RW, Collins KS (2002). "Epidural anaesthesia and analgesia and outcome of major surgery: a randomised trial". Lancet. 359 (9314): 1276–82. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(02)08266-1. PMID 11965272. S2CID 13702406.

- Tubben RE, Murphy PB (2018), "Epidural Blood Patch", StatPearls, StatPearls Publishing, PMID 29493961, retrieved October 31, 2018

- Corning, JL (1885). "Spinal anaesthesia and local medication of the cord". New York Medical Journal. 42: 483–5.

- Marx, GF (1994). "The first spinal anesthesia. Who deserves the laurels?". Regional Anesthesia. 19 (6): 429–30. PMID 7848956.

- Dogliotti, AM (1933). "Research and clinical observations on spinal anesthesia: with special reference to the peridural technique". Current Researches in Anesthesia & Analgesia. 12 (2): 59–65.

- Curelaru I, Sandu L (June 1982). "Eugen Bogdan Aburel (1899-1975). The pioneer of regional analgesia for pain relief in childbirth". Anaesthesia. 37 (6): 663–9. doi:10.1111/j.1365-2044.1982.tb01279.x. PMID 6178307.

- Goerig M, Freitag M, Standl T (December 2002). "One hundred years of epidural anaesthesia—the men behind the technical development". International Congress Series. 1242: 203–212. doi:10.1016/s0531-5131(02)00770-7.

- Edwards WB, Hingson RA (1942). "Continuous caudal anesthesia in obstetrics". American Journal of Surgery. 57 (3): 459–64. doi:10.1016/S0002-9610(42)90599-3.

- Hingson RA, Edwards WE (1943). "Continuous Caudal Analgesia in Obstetrics". Journal of the American Medical Association. 121 (4): 225–9. doi:10.1001/jama.1943.02840040001001.

- Martinez Curbelo, M (1949). "Continuous peridural segmental anesthesia by means of a ureteral catheter". Current Researches in Anesthesia & Analgesia. 28 (1): 13–23. doi:10.1213/00000539-194901000-00002. PMID 18105827.

- Behar, M; Olshwang, D; Magora, F; Davidson, J (1979). "Epidural morphine in treatment of pain". The Lancet. 313 (8115): 527–529. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(79)90947-4. PMID 85109. S2CID 37432948.

Further reading

- Boqing Chen and Patrick M. Foye, UMDNJ: New Jersey Medical School, Epidural Steroid Injections: Non-surgical Treatment of Spine Pain, eMedicine: Physical Medicine and Rehabilitation (PM&R), August 2005. Also available online.

- Leighton BL, Halpern SH (2002). "The effects of epidural analgesia on labor, maternal, and neonatal outcomes: a systematic review". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 186 (5 Suppl Nature): S69–77. doi:10.1067/mob.2002.121813. PMID 12011873.

- Zhang J, Yancey MK, Klebanoff MA, Schwarz J, Schweitzer D (2001). "Does epidural analgesia prolong labor and increase risk of cesarean delivery? A natural experiment". Am J Obstet Gynecol. 185 (1): 128–34. doi:10.1067/mob.2001.113874. PMID 11483916.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Epidural anaesthesia. |

- Epidurals for pain relief in labour Comprehensive information with women's stories – informedhealthonline.org, Accessed July 2, 2009.

- What Is An Epidural Headache? – Epidural Headaches Explained

- MedlinePlus Encyclopedia

-solution.jpg)