Embryology

Embryology (from Greek ἔμβρυον, embryon, "the unborn, embryo"; and -λογία, -logia) is the branch of biology that studies the prenatal development of gametes (sex cells), fertilization, and development of embryos and fetuses. Additionally, embryology encompasses the study of congenital disorders that occur before birth, known as teratology.

Early embryology was proposed by Marcello Malpighi, and known as preformationism, the theory that organisms develop from pre-existing miniature versions of themselves. Then Aristotle proposed the theory that is now accepted, epigenesis. Epigenesis is the idea that organisms develop from seed or egg in a sequence of steps. Modern embryology developed from the work of Karl Ernst von Baer, though accurate observations had been made in Italy by anatomists such as Aldrovandi and Leonardo da Vinci in the Renaissance.

Contents

Comparative Embryology

Preformationism and Epigenesis

As recently as the 18th century, the prevailing notion in western human embryology was preformation: the idea that semen contains an embryo – a preformed, miniature infant, or homunculus – that simply becomes larger during development.

The competing explanation of embryonic development was epigenesis, originally proposed 2,000 years earlier by Aristotle. Much early embryology came from the work of the Italian anatomists Aldrovandi, Aranzio, Leonardo da Vinci, Marcello Malpighi, Gabriele Falloppio, Girolamo Cardano, Emilio Parisano, Fortunio Liceti, Stefano Lorenzini, Spallanzani, Enrico Sertoli, and Mauro Rusconi. According to epigenesis, the form of an animal emerges gradually from a relatively formless egg. As microscopy improved during the 19th century, biologists could see that embryos took shape in a series of progressive steps, and epigenesis displaced preformation as the favored explanation among embryologists.

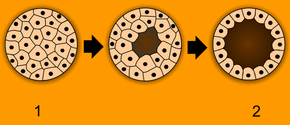

Cleavage

Cleavage is the very beginning steps of a developing embryo. Cleavage refers to the many mitotic divisions that occur after the egg is fertilized by the sperm. The ways in which the cells divide is specific to certain types of animals and may have many forms.

Holoblastic

Holoblastic cleavage is the complete division of cells. Holoblastic cleavage can be radial (see: Radial cleavage), spiral (see: Spiral cleavage), bilateral (see: Bilateral cleavage), or rotational (see: Rotational cleavage). In holoblastic cleavage the entire egg will divide and become the embryo, whereas in meroblastic cleavage some cells will become the embryo and others will be the yolk sac.

Meroblastic

Meroblastic cleavage is the incomplete division of cells. The division furrow does not protrude into the yolky region as those cells impede membrane formation and this causes the incomplete separation of cells. Meroblastic cleavage can bilateral (see: Bilateral cleavage), discoidal (see: Discoidal cleavage), or centrolecithal (see: Centrolecithal).

Basal Phyla

Animals that belong to the basal phyla have holoblastic radial cleavage which results in radial symmetry (see: Symmetry in biology). During cleavage there is a central axis that all divisions rotate about. The basal phyla also has only one to two embryonic cell layers, compared to the three in bilateral animals (endoderm, mesoderm, and ectoderm).

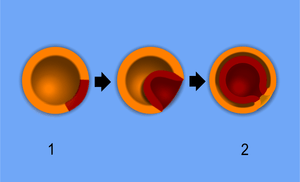

Bilaterians

In bilateral animals cleavage can be either holoblastic or meroblastic depending on the species. During gastrulation the blastula develops in one of two ways that divide the whole animal kingdom into two halves (see: Embryological origins of the mouth and anus). If in the blastula the first pore, or blastopore, becomes the mouth of the animal, it is a protostome; if the blastopore becomes the anus then it is a deuterostome. The protostomes include most invertebrate animals, such as insects, worms and molluscs, while the deuterostomes include the vertebrates. In due course, the blastula changes into a more differentiated structure called the gastrula. Soon after the gastrula is formed, three distinct layers of cells (the germ layers) from which all the bodily organs and tissues then develop.

Germ Layers

- The innermost layer, or endoderm, give rise to the digestive organs, the gills, lungs or swim bladder if present, and kidneys or nephrites.

- The middle layer, or mesoderm, gives rise to the muscles, skeleton if any, and blood system.

- The outer layer of cells, or ectoderm, gives rise to the nervous system, including the brain, and skin or carapace and hair, bristles, or scales.

Drosophila melanogaster (fruit fly)

Drosophila have been used as a developmental model for many years. The studies that have been conducted have discovered many useful aspects of development that not only apply to fruit flies but other species as well.

Outlined below is the process that leads to cell and tissue differentiation.

- Maternal-effect genes help to define the anterior-posterior axis using Bicoid (gene) and Nanos (gene).

- Gap genes establish 3 broad segments of the embryo.

- Pair-rule genes define 7 segments of the embryo within the confines of the second broad segment that was defined by the gap genes.

- Segment-polarity genes define another 7 segments by dividing each of the pre-existing 7 segments into anterior and posterior halves using a gradient of Hedgehog and Wnt.

- Homeotic (Hox) genes use the 14 segments as pinpoints for specific types of cell differentiation and the histological developments that correspond to each cell type.

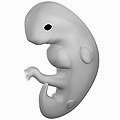

Humans

Humans are bilateral animals that have holoblastic rotational cleavage. Humans are also deuterostomes. In regard to humans, the term embryo refers to the ball of dividing cells from the moment the zygote implants itself in the uterus wall until the end of the eighth week after conception. Beyond the eighth week after conception (tenth week of pregnancy), the developing human is then called a fetus.

Evolutionary Embryology

Evolutionary embryology is the expansion of comparative embryology by the ideas of Charles Darwin. Similarly to Karl Ernst von Baer's principles that explained why many species often appear similar to one another in early developmental stages, Darwin argued that the relationship between groups can be determined based upon common embryonic and larval structures.

Von Baer's Principles

- The general features appear earlier in development than do the specialized features.

- More specialized characters develop from the more general ones.

- The embryo of a given species never resembles the adult form of a lower one.

- The embryo of a given species does resemble the embryonic form of a lower one.[1]

Using Darwin's theory evolutionary embryologists have since been able to distinguish between homologous and analogous structures between varying species. Homologous structures are those that the similarities between them are derived from a common ancestor, such as the human arm and bat wings. Analogous structures are those that appear to be similar but have no common ancestral derivation.[1]

Origins of Modern Embryology

Until the birth of modern embryology through observation of the mammalian ovum by Karl Ernst von Baer in 1827, there was no clear scientific understanding of embryology. Only in the late 1950s when ultrasound was first used for uterine scanning, was the true developmental chronology of human fetus available. Karl Ernst von Baer along with Heinz Christian Pander, also proposed the germ layer theory of development which helped to explain how the embryo developed in progressive steps. Part of this explanation explored why embryos in many species often appear similar to one another in early developmental stages using his four principles.

Modern Embryology Research

Embryology is central to evolutionary developmental biology ("evo-devo"), which studies the genetic control of the development process (e.g. morphogens), its link to cell signalling, its roles in certain diseases and mutations, and its links to stem cell research. Embryology is the key to Gestational Surrogacy, which is when the sperm of the intended father and egg of intended mother are fused in a lab forming an embryo. This embryo is then put into the surrogate who carries the child to term.

Medical Embryology

Medical embryology is used widely to detect abnormalities before birth. 2-5% of babies are born with an observable abnormality and medical embryology explores the different ways and stages that these abnormalities appear in.[1] Genetically derived abnormalities are referred to as malformations. When there are multiple malformations, this is considered a syndrome. When abnormalities appear due to outside contributors, these are disruptions. The outside contributors causing disruptions are known as teratogens. Common teratogens are alcohol, retinoic acid[2], ionizing radiation or hyperthermic stress.

Vertebrate and Invertebrate Embryology

Many principles of embryology apply to invertebrates as well as to vertebrates. Therefore, the study of invertebrate embryology has advanced the study of vertebrate embryology. However, there are many differences as well. For example, numerous invertebrate species release a larva before development is complete; at the end of the larval period, an animal for the first time comes to resemble an adult similar to its parent or parents. Although invertebrate embryology is similar in some ways for different invertebrate animals, there are also countless variations. For instance, while spiders proceed directly from egg to adult form, many insects develop through at least one larval stage. For decades, a number of so-called normal staging tables were pruduced for the embryology of particular species, mainly focussing on external developmental characters. As variation in developmental progress makes comparison among species difficult, a character-based Standard Event System was developed, which documents these differences and allows for phylogenetic comparisons among species.[3]

Birth of Developmental Biology

After the 1950s, with the DNA helical structure being unraveled and the increasing knowledge in the field of molecular biology, developmental biology emerged as a field of study which attempts to correlate the genes with morphological change, and so tries to determine which genes are responsible for each morphological change that takes place in an embryo, and how these genes are regulated.

- Human embryos by Leonardo da Vinci

- Human embryo at six weeks gestational age

- Histological film 10-day mouse embryo

As of today, human embryology is taught as a cornerstone subject in medical schools, as well as in biology and zoology programs at both an undergraduate and graduate level.

Human embryos by Leonardo da Vinci

Human embryos by Leonardo da Vinci Human embryo at six weeks gestational age

Human embryo at six weeks gestational age Histological film 10-day mouse embryo

Histological film 10-day mouse embryo

As of today, human embryology is taught as a cornerstone subject in medical schools, as well as in biology and zoology programs at both an undergraduate and graduate level.

See also

- Abortion

- Embryogenesis

- Embryonic differentiation waves

- Embryology of digestive system and the body cavities

- French flag model

- Morphogen

- Ontogeny

- Recapitulation theory

References

Citations

- Gilbert, Scott F., 1949- (15 June 2016). Developmental biology. Barresi, Michael J. F., 1974- (Eleventh ed.). Sunderland, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-1-60535-470-5. OCLC 945169933.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Soprano, Dianne Robert; Soprano, Kenneth J. (1 July 1995). "Retinoids as Teratogens". Annual Review of Nutrition. 15 (1): 111–132. doi:10.1146/annurev.nu.15.070195.000551. ISSN 0199-9885. PMID 8527214.

- Werneburg, Ingmar (2009). "A Standard System to Study Vertebrate Embryos". PLoS ONE. 4 (6): 1–16. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0005887.

Sources

- Embryology - History of embryology as a science." Science Encyclopedia. Web. 06 Nov. 2009. <http://science.jrank.org/pages/2452/Embryology.html>.

- "Germ layer." Encyclopædia Britannica. 2009. Encyclopædia Britannica Online. 06 Nov. 2009 <http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/230597/germ-layer>.

- Welton, John. “| Circle Surrogacy.” Circle Surrogacy, Full Service, Worldwide Surrogate-Parenting Agency, www.circlesurrogacy.com/about/what-is-surrogacy.

Further reading

- Apostoli, Pietro; Catalani, Simona (2011). "Chapter 11. Metal Ions Affecting Reproduction and Development". In Astrid Sigel, Helmut Sigel and Roland K. O. Sigel (ed.). Metal Ions in Toxicology. Metal Ions in Life Sciences. 8. RSC Publishing. pp. 263–303. doi:10.1039/9781849732116-00263. ISBN 978-1-84973-091-4.

- Scott F. Gilbert. Developmental Biology. Sinauer, 2003. ISBN 0-87893-258-5.

- Lewis Wolpert. Principles of Development. Oxford University Press, 2006. ISBN 0-19-927536-X.

- Carlson, Bruce M.; Kantaputra, Piranit N. (2014). Human embryology and developmental biology. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier/Saunders. ISBN 978-1-4557-2794-0. (click here for more information)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Embryology. |

| Wikisource has the text of the 1911 Encyclopædia Britannica article Embryology. |

- Online course in embryology

- Indiana University's Human Embryology Animations

- UNSW Embryology Large resource of information and media.

- What is a human admixed embryo?

- Definition of embryo according to Webster