Turkmen literature

Turkmen literature (Turkmen: Türkmen edebiýaty) comprises oral compositions and written texts in Old Oghuz Turkic and Turkmen languages. Turkmens are direct descendants of the Oghuz Turks, who were a western Turkic people that spoke the Oghuz branch of the Turkic language family.

| This article is part of a series on the |

| Culture of Turkmenistan |

|---|

|

| Society |

| Arts and literature |

| Other |

| Symbols |

|

Turkmenistan portal |

The history of the common Turkic literature spans a period of nearly 1,300 years.[1] The oldest records of written Turkic are found on runic inscriptions, the most famous of which is the Orhon inscriptions dating to the 7th century. Later, between the 9th and 11th centuries, a tradition of oral epics, such as the Book of Dede Korkut of the Oghuz Turks—the linguistic and cultural ancestors of the modern Turkish, Turkmen and Azerbaijani peoples—and the Manas epic of the Kyrgyz people arose among the nomadic Turkic peoples of Central Asia.

After the Battle of Manzikert, the Oghuz Turks began to settle in Anatolia starting from the 11th century, and in addition to the earlier oral traditions, a written literary tradition, heavily influenced by Arabic and Persian literature, emerged among these new settlers.[2]

The earliest development of the Turkmen literature is closely associated with the literature of the Oghuz Turks.[3] Turkmens have joint claims to a great number of literary works written in Old Oghuz and Persian (by Seljuks in 11-12th centuries) languages with other people of the Oghuz Turkic origin, mainly of Azerbaijan and Turkey. This works include, but are not limited to the Book of Dede Korkut, Gorogly, Layla and Majnun, Yusuf Zulaikha and others.[4]

There is general consensus, however, that distinctively modern Turkmen literature originated in the 18th century with the poetry of Magtymguly Pyragy, who is considered the father of the Turkmen literature.[5][6] Other prominent Turkmen poets of that era are Döwletmämmet Azady (Magtymguly's father), Nurmuhammet Andalyp, Abdylla Şabende, Şeýdaýy, Mahmyt Gaýyby and Gurbanally Magrupy.[7]

History

Turkmen literature is closely associated with the earliest Turkic literature commonly shared by all Turkic peoples. The earliest known examples of Turkic poetry date to sometime in the 6th century AD and were composed in the Uyghur language. Some of the earliest verses attributed to Uyghur Turkic writers are only available in Chinese language translations. During the era of oral poetry, the earliest Turkic verses were intended as songs and their recitation a part of the community's social life and entertainment.[8]

Of the long epics, only the Oğuzname survived in its entirety.[9] The Book of Dede Korkut may have had its origins in the poetry of the 10th century but remained an oral tradition until the 15th century. The earlier written works Kutadgu Bilig and Dīwān Lughāt al-Turk date to the second half of the 11th century and are the earliest known examples of Turkic literature with few exceptions.[10]

One of the most important figures of the Oghuz Turkic (Turkoman) literature was the 13th century Sufi poet Yunus Emre. The golden age of the Turkoman literature is thought to have lasted from the 10th century until the 17th century.[11]

Emergence of the distinct Turkmen literature

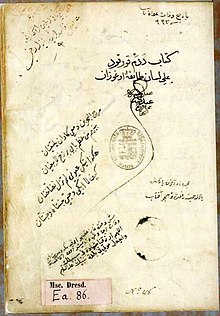

The first experience of using close to modern Turkmen language in written literature dates back to the 15–16th centuries. Modern Turkmen elements can be seen in the works written in Chagatai language in the common Turkic literature. The influence of the Chagatai language on Turkmen literature remained significant even later. The most ancient monuments of the distinct Turkmen literature are the religious and moral composition of the Khorosani Turkmen, Vafayi, called Rownak-ul-Islam (The light of Islam), (1464), written in poetic form; the verses of Bayram Khan (16th century), the work of Abu al-Ghazi Bahadur, "Genealogy of the Turkmens" (17th century).[12]

An analysis of the language and content of the anonymous novels recorded of the 19th century - Asly Kerem, Şasenem we Garyp, Görogly, Hürlukga we Hemra, Melike Dilaram, Ibrahim and Edehem, Zeýnal-Arap, Baba Röwşen, etc., show that they were originally written in the 15-17th centuries, and were composed according to the so-called "wandering plots" known throughout the East. They glorified the triumph of love, bravery and courage of heroes who overcome obstacles and fight against the forces of evil, personified by fantastic creatures - devs, jinn, peri, etc. These creatures, on the contrary, help the heroes in solving difficult problems in the novels of Hürlukga we Hemra, Saýatly Hemra, Görogly, and Şasenem we Garyp. The novels of Baba Röwşen, Melike Dilaram and others are about the struggle of the representatives of Islam, Ali and his followers - against the "infidels". The peculiarity of the literary form of these novels is the alternation of prose and poetic passages.[13]

The surviving oral Turkmen folklore - fairy tales, songs, anecdotes, proverbs, sayings, tongue twisters, etc. - along with the heroes of noble origin, there are characters from the common people - Aldar Köse, Kelje, Dälije, Aklamyh gyzlary, Gara atly gyz, and others. They emerge victorious in difficult situations thanks to their diligence, dexterity, resourcefulness and courage. An integral part of the literary process in Turkmenistan has always been the folk poet-improviser or shahir (şahyr), usually illiterate.[14][15]

Golden age

18-19th centuries are considered the era when Turkmen poetry flourished, as it was marked by the appearance of such poets as Azady, Andalyp, Pyragy, Şeýdaýy, Zelili, Gaýyby, and others.

Döwletmämmet Azady is known for his religious and didactic treatise Wagzy Azat (Sermon of Azad), written in the form of individual poems and short tales, as well as the poem "Jabyr Ensar" and lyric poems. The poet Andalyp, who lived at the same time, is the author of the lyric works and novels such as "Yusup and Zalaikha", "Laila and Majnun", "Sagd-Vekas". The language of the poetry of Azady and Andalyp is far from the folk language and is oriented towards the canons of oriental court poetry.[16]

Magtymguly Pyragy

The figure of the comprehensively educated poet and philosopher Magtymguly Pyragy, the son of Azady, became a turning point for the Turkmen literature in terms of expanding the theme of literary works, addressing the national language and the entire nation. It is widely believed that Magtumguly wrote nearly 800 poems, although many may be apocryphal. A bulk of them are constructed in the form of goshgï (folk songs), while other poems are composed as personal ghazals that include Sufi elements. In the 19th century, Makhtumguly’s poems travelled across the Central Asia orally rather than in the written form; enabling them to achieve wide popularity among many other people, including Karakalpaks, Tajiks and Kurds.[17]

In his poems, of which more than 300 have survived, references to almost all countries, sciences, and literary sources known in his time can be found. He crossed the clan and tribal boundaries, and through his works expressed the aspiration of all Turkmens to unite. The poet widely used the vernacular language, many of his poetic lines turned into folk proverbs and sayings. The bold disclosure of the contradictions of the era, the deep sincerity, the highly artistic significance of the poetry of Magtymguly made his works a model for others and were imitated later by the best representatives of Turkmen literature.[18]

The following is the excerpt from Magtyguly's "Aýryldym" (Separated) poem dedicated to Meňli, a girl he loved in his youth (in original Turkmen and its English translation):[19]

|

Aýryldym gunça gülümden.

|

I am separated from my flower.

|

Şeýdaýy, Magrupy and others

At the end of the 18th century, while maintaining the influence of the Chagatai language, the convergence of the written language with the spoken language began. Creative poetry of the late 18th and early 19th centuries were represented by such names as Şeýdaýy (fantasy novel "Gül we Senuwer", and lyric poems) and Gaýyby (collection of 400 poems). The novelist Magrupy is the author of the heroic novel "Ýusup we Ahmet" and the love story "Seýfel Melek".[20]

The following is the excerpt from Magrupy's "Ýusup we Ahmet" (in original Turkmen and its English translation):[21]

|

Ahmet beg diýer, meni göze almadyň,

|

Ahmet bey says, you have not understood me,

|

Early 19th century is marked by the appearance of a significant number of poets and prose writers writing in the Turkmen language. This is, first of all, Şabende - the author of lyric poems and science fiction novels and stories "Gül we Bilbil" (Rose and the Nightingale), Şabehrem, Hojaýy Berdi Han, Nejep Oglan, who praised bravery, selflessness, heroism in the fight against enemies. The poet Mollanepes is the author of the novel "Zöhre we Tahyr", which exposes the treachery of the shahs and courtiers, glorifies the triumph of truth and love and, like "Gül we Bilbil" of Şabende, refers to the masterpieces of Turkmen literature. The poetry of Mollanepes is distinguished by the brightness and power of images, by a rich language.[22]

In the works of poets of the first half of the 19th century, such as Seýdi, Zelili, and Kemine, themes dominated by social motives are present. The poet-warrior Seýdi (1758–1830) fought against the Emirate of Bukhara, and called on the Turkmen tribes to unite and fight for freedom. Zelili (1790–1844) described the suffering of the Etrek Turkmens, oppressed by the baýs (rich people), mullahs, the Khanate of Khiva and Iranian rulers. He praised earthly joys and exposed the bribery and cruelty of the ruling classes. The singer of the poorest peasantry, Kemine (died in 1840), wrote about love of free choice, his native region, and composed numerous short funny short tales or anecdotes.[23]

In the middle of the 19th century, poets Dosmämmet, Aşyky, Allazy, Zynhary, Ýusup Hoja, Baýly, Allaguly, and Garaoglan were widely known, however, only couple of their poems have survived. In the 1860s, the famous historical poem by Abdysetdar Kazy, "Jeňnama", about the battles of the Teke (Turkmens) with the Iranians, was composed.[24]

Literature during the Russian Turkestan era

In the 1880s, Turkestan was conquered by the Russians, and the poets Mätäji (1824–1884) and Misgin Gylyç (1845–1905) wrote about the heroic defense of Gökdepe fortress, the last stronghold of the Turkmens who fought against the tsarist army. They also wrote social and love lyrics.[25]

In the 19th century, the first printed books appeared in the Turkmen language. In the pre-revolutionary schools of Turkestan, an artificial "Central Asian-Chagatai" language was taught, but the overwhelming majority of the population was illiterate. The modern Turkmen language began to form at the beginning of the 20th century, based on the Teke dialect of the Turkmen language. In 1913, the first Russian-Turkmen dictionary was published under the editorship of I.A. Belyaev. "The Grammar of the Turkmen language" was also published under his editorship in 1915.[26]

Soviet influence

Early years after the October Revolution

Early 20th century was marked by the emergence of new topics in Turkmen literature - criticism of the ignorance of the Muslim clergy, remnants of the old way of life, propaganda of ideas of enlightenment. These themes are present in the works of the writers Molla Durdy, Biçäre Mohammet Gylyç (died in 1922), and others. The Soviet period of Turkmen literature manifested itself in new themes in the works of the shahirs and the first Soviet Turkmen writers and poets. The process was accompanied by overcoming the ideological heritage of Jadidism, comprehending new Soviet images, ideas and realities.

The first songs about October, about Lenin and Stalin, about the struggle of the Red Army were composed by the shahirs Baýram and Kermolla. Poets Durdy Gylyç (b. 1886) and Ata Salyh (b. 1908) significantly expanded the theme of their songs, they composed songs about the successes of socialist construction and the victories of the world proletariat, the Stalinist constitution and friendship of the peoples of the USSR, collective farm construction, liberated women, hero pilots, defeating enemies. These themes became the basis for the creativity of many famous shahirs of the Soviet period - Halla, Töre, Oraz Çolak, etc. Many of them were awarded orders and medals by the Soviet government.[27]

In the 20th century, several times the question was raised about the translation of the Turkmen script, which previously existed on the basis of the Arabic alphabet, into other types of alphabets. In 1928, after the congress of Turkologists in Baku in 1926, the Turkmen script was translated into the Latin alphabet and existed in this form until 1940, when, as in all the Turkic republics of the USSR, the writing was translated into Cyrillic with the addition of some additional letters. In 1993, Turkmenistan again returned to the Latin alphabet, however, Turkmens outside Turkmenistan continue to use the Arabic alphabet.[28]

The first Soviet Turkmen poet, Molla Murt (1879–1930), from the first days of the socialist revolution, glorified socialism in his poems in a simple and understandable language for the people. The first Soviet prose writer Agahan Durdyýew (b. 1904), in his works "In the Sea of Dreams", "Wave of Shock Workers", "Meret", "Gurban", "Beauty in the Claws of the Golden Eagle", wrote about the construction in the Garagum desert, about the problems facing the liberation of the women of the East, etc.[29]

The romance of socialist construction was also reflected in the works of other Turkmen writers: these are Durdy Agamämmedow (b. 1904) and his poems and plays about "The collective farm life of Sona", the collective farm system, "the Son of October"; Beki Seýtäkow (b. 1914) and his humorous poems, "stories by Akjagül", "Communar", poem "On Fire"; Alty Garlyýew and his plays "Cotton, Annagül", "Aýna", 1916; the first Turkmen woman, playwright and poetess Towşan Esenowa (b. 1915) and her comedy from the collective farm life "The daughter of a millionaire", the poem "Steel Girls", "Lina".[30]

Berdi Kerbabayev

The most prominent figure among the Soviet Turkmen writers is Berdi Kerbabaýew, Academician of the Academy of Sciences of the Turkmen SSR, Hero of the Socialist Labour (b. 1894). In the 1920s, he began to publish as a poet-satirist. In the poems "Maiden's World" (1927) and "Fortified, or The Victim of Adat" (1928), he advocated the establishment of Soviet moral norms and deliverance from the remnants of the past. For the first Turkmen revolutionary historical novel "The Decisive Step" (1947), he was awarded the title of laureate of the USSR State Prize (1948). During the Great Patriotic War, the story "Gurban Durdy" (1942), the poem "Aýlar" (1943), the plays "Brothers" (1943) and "Magtymguly" (1943) were written. From 1942 to 1950, he was the chairman of the Writers' Union of Turkmenistan. After the war, Kerbabaýew's works about the life of a collective farm village were published - the story "Aýsoltan from the country of white gold" (1949, USSR State Prize 1951), about the life of oil workers - the novel "Nebit-Dag" (1957), the historical novel "Miraculously Born" (1965) about the Turkmen revolutionary K. Atabaýew. Kerbabaýew was also involved in translating the works of Russian and Soviet poets and writers into Turkmen.[31][32]

There are many more poets and writers whose literary creativity was revealed during the years of the USSR: Kemal Işanow, Saryhanov, Ata Gowşudow,[33] Meret Gylyjow, Pomma-Nur Berdiýew, Çäry Gulyýew, Monton Janmyradow, Ahmet Ahundow-Gürgenli, Seýidov, Hemraýew and others. In general, Turkmen literature of the 1920-1990 period developed within the framework of the Soviet culture, mastering the images of socialist realism, adjusted for Turkmen specificity.

The undoubted achievements of the Soviet period include the significant research work carried out by the Soviet historians and linguists, who discovered in the sources of the 15th to 16th centuries the most ancient literary works in the Turkmen language.

After Independence

In the 1990s, after the proclamation of independence of Turkmenistan, tendencies began to appear in the literature reflecting new trends.[34] However, it is impossible to fully illuminate the state and ways of development of the modern Turkmen literature and talk about the work of the poets and prose writers of the present. Each of them perceives reality in its own way, each has its own theme and style of presentation.

Agageldi Allanazarow's novel "The Seal" deals with emotional experiences of the heroes, traditions and moral foundations of the Turkmen people.[35] The work of Hudaýberdi Diwangulyýew, "Return to Yekagach", reveals the character of the heroes in difficult conditions, when they, using their deep knowledge and experience, with honor get out of the most difficult situations. It is optimistic, calls for the unification of people's efforts in solving the grandiose tasks of deep scientific knowledge of the world around them.

A distinctive feature of the prose of Kömek Gulyýew, whose story "Every fairy tale has its own end" is a peculiar manner of presentation with a soft, good-natured humor, a subtle knowledge of human psychology and a comprehensive disclosure of the characters of their heroes.

Poems and rubayis of Atamyrat Atabaýew are permeated with a sensitive concern for the future of the country, they contain deep reflections on the relationship between people in new conditions, in an Independent and Neutral Turkmen land. They contain bright feelings of filial love for the Motherland, respect for her history and glorious deeds of ancestors.

There are countless other comtemporary poets and writes, such as Orazguly Annaýew, Gurbanýaz Daşgynow, Gurbannazar Orazgulyýew and others, whose works are popular not only in Turkmenistan, but in the post-Soviet countries as well.[36]

See also

- Turkmen people

- Turkmen language

- Turkmen culture

- Magtymguly Pyragy

Notes and references

- "Silk Roads programme". Retrieved 13 April 2016.

- Babyr (2004). Diwan. Ashgabat: Miras. p. 7.

- Johanson, L. (6 April 2010). Brown, Keith; Ogilvie, Sarah (eds.). Concise Encyclopedia of Languages of the World. Elsevier. pp. 110–113. ISBN 978-0-08-087775-4 – via Google Books.

- Akatov, Bayram (2010). Ancient Turkmen Literature, the Middle Ages (X-XVII centuries) (in Turkmen). Turkmenabat: Turkmen State Pedagogical Insitute, Ministry of Education of Turkmenistan. pp. 29, 39, 198, 231.

- "Turkmenistan Culture". Asian recipe.

- Levin, Theodore; Daukeyeva, Saida; Kochumkulova, Elmira (2016). Music of Central Asia. Indiana University press. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-253-01751-2.

- "Nurmuhammet Andalyp". Dunya Turkmenleri.

- Halman, Talat. A Millenium of Turkish Literature. pp. 4–6.

- Halman, Talah. A Millenium of Turkish Literature. pp. 4–5.

- Halman, Talah. A Millenium of Turkish Literature. p. viii.

- Akatov, Bayram (2010). Ancient Turkmen Literature, the Middle Ages (X-XVII centuries) (in Turkmen). Turkmenabat: Turkmen State Pedagogical Insitute, Ministry of Education of Turkmenistan. p. 9.

- "National Calendar (in Turkmen)". Turkmen Sahra.

- Janos Sipos, Ethnomusicology Ireland 5, Collecting Folk Music in the Land of the Zemzems: Report on the Turkmen expedition of 2011, pp. 163-170

- Janos Sipos, Ethnomusicology Ireland 5, Collecting Folk Music in the Land of the Zemzems: Report on the Turkmen expedition of 2011, p. 164

- Tales on Aldar Kose (in Russian)

- Proceedings of the Institute of Language and Literature. Issue 1–4, Ashgabat, 1957–1960.

- "Turkmen Literature". Encyclopedia Britannica.

- Proceedings of the Institute of Language and Literature. Issue 1–4, Ashgabat, 1957–1960.

- "Aýryldym". Türkmen kultur ojagynyň internet sahypasy (Website of the Turkmen Culture).

- Levin, Theodore; Daukeyeva, Saida; Kochumkulova, Elmira (2016). Music of Central Asia. Indiana University Press. p. 138.

- Levin, Theodore; Daukeyeva, Saida; Kochumkulova, Elmira (2016). Music of Central Asia. Indiana University press. p. 138-139. ISBN 978-0-253-01751-2.

- Mollanepes and the life of the Turkmen in the 19th century: materials of the International Scientific Conference. Mary, April 8-10, 2010. National Institute of Manuscripts of the Academy of Sciences of Turkmenistan. Mary, 2010.

- "Mammetweli Kemine". Gollanma.

- Russian bibliography

- "Annagylych Mataji". Dunya Turkmenleri.

- Belyayev, Ivan Aleksandrovich (1915). The Grammar of the Turkmen Language. Russian State Library.

- Big Soviet Encyclopedia. Vol. 2. 2nd ed. 1950. p. 344

- Soyegov, M. New Turkmen Alphabet: several questions on its development and adoption

- "Agahan Durdiyew". Gollanma.

- Sidelnikova L.M. The Way of the Soviet Poetess. Ashgabat, 1970.

- "Kerbabayev Berdi Muradovich (in Russian)". ЦентрАзия. Retrieved 2013-04-07.

- {{A. Кerbabayeva, "Life — like house: its foundation must be laid deeply and firmly!" (in Russian) |url=http://www.velykoross.ru/journals_pdfs/0/7.pdf|publisher=Великороссъ

- A. Aborskiy, Ata Gowshudov. Sketch of life and work (in Russian), Аshgabat, 1965.

- Tuwakow, M (2010). Main issues of the Modern Turkmen Literature (in Turkmen). Ashgabat: Turkmen State University named after Magtymguly. pp. 7–8.

- Allanazarow A. "The Seal". Asghabat, 2007. pp 1-192.

- Agaliyev, K. "On the Modern Turkmen Literature". Siberian Lights.