Eel River (California)

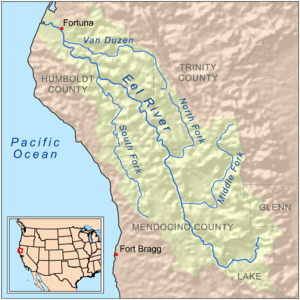

The Eel River (Cahto: Taanchow)[5] is a major river, about 196 miles (315 km) long, of northwestern California. The river and its tributaries form the third largest watershed entirely in California, draining a rugged area of 3,684 square miles (9,540 km2) in five counties. The river flows generally northward through the Coast Ranges west of the Sacramento Valley, emptying into the Pacific Ocean about 10 miles (16 km) downstream from Fortuna and just south of Humboldt Bay. The river provides groundwater recharge, recreation, and industrial, agricultural and municipal water supply.[6]

| Eel River | |

|---|---|

The river near Dyerville, California | |

Map of the Eel River drainage basin | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| County | Humboldt, Lake, Mendocino, Trinity |

| City | Fortuna |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Pacific Coast Ranges |

| • location | Mendocino County, California |

| • coordinates | 39°36′51″N 122°58′12″W[1] |

| • elevation | 6,245 ft (1,903 m)[2] |

| Mouth | Pacific Ocean |

• location | Humboldt County, California |

• coordinates | 40°38′29″N 124°18′44″W[1] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 196 mi (315 km)[1] |

| Basin size | 3,684 sq mi (9,540 km2)[3] |

| Discharge | |

| • location | mouth, near Fortuna[4] |

| • average | 9,503 cu ft/s (269.1 m3/s)[4] |

| • minimum | 10 cu ft/s (0.28 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 935,800 cu ft/s (26,500 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | South Fork Eel River |

| • right | Middle Fork Eel River, North Fork Eel River, Van Duzen River |

| Type | Wild, Scenic, Recreational |

| Designated | January 19, 1981 |

The Eel River system is among the most dynamic in California because of the region's unstable geology and the influence of major Pacific storms. The discharge is highly variable; average flows in January and February are over 100 times greater than in August and September.[7] The river also carries the highest suspended sediment load of any river of its size in the United States, in part due to the frequent landslides in the region.[4] However, the river basin also supports abundant forests – including some of the world's largest trees in Sequoia sempervirens (Coastal redwood) groves – and historically, one of California's major salmon and steelhead trout runs.

The river basin was lightly populated by Native Americans before, and for decades after the European settlement of California. The region remained little traveled until 1850, when Josiah Gregg and his exploring party arrived in search of land for settlement. The river was named after they traded a frying pan to a group of Wiyot fishermen in exchange for a large number of Pacific lampreys, which the explorers thought were eels.[8]:91[9] Explorers' reports of the fertile and heavily timbered region attracted settlers to Humboldt Bay and the Eel River Valley. Starting in the late 19th century the Eel River supported a large salmon canning industry which began to decline by the 1920s due to overfishing. The Eel River basin has also been a significant source of timber since the days of early settlement and continues to support a major logging sector. The river valley was a major rail transport corridor (Northwestern Pacific Railroad) throughout the 20th century and also forms part of the route of Redwood Highway (US Highway 101).

Since the early 20th century, the Eel River has been dammed in its headwaters to provide water, via interbasin transfer, to parts of Mendocino and Sonoma Counties. During the 1950s and 1960s, there was great interest in building much larger dams in the Eel River system, in order to provide water for the State Water Project. Although the damming would have relieved pressure on California's overburdened water systems, it stirred up decades of controversy, as some of the proposals made little economic sense and would have been detrimental to an ailing salmon run. The Eel was granted federal Wild and Scenic River status in 1981, formally making it off limits to new dams.[10] Nevertheless, logging, grazing, road-building and other human activities continue to significantly affect the watershed's ecology.

Course

The Eel River originates on the southern flank of 6,740-foot (2,050 m) Bald Mountain, in the Upper Lake Ranger District of the Mendocino National Forest in Mendocino County.[1] The river flows south through a narrow canyon in Lake County before entering Lake Pillsbury, the reservoir created by Scott Dam. Below the dam the river flows west, re-entering Mendocino County. At the small Cape Horn Dam about 15 miles (24 km) east of Willits, water is diverted from the Eel River basin through a 1-mile (1.6 km) tunnel to the Russian River, in a scheme known as the Potter Valley Project.

Below the dam the river turns north, flowing through a long isolated valley, receiving Outlet Creek from the west and then the Middle Fork Eel River from the east at Dos Rios. About 20 miles (32 km) downstream, the North Fork Eel River – draining one of the most rugged and remote portions of the watershed – joins from the east. Between the North and Middle Forks the Round Valley Indian Reservation lies east of the Eel River. After this confluence the Eel flows briefly through southwestern Trinity County, past Island Mountain, before entering Humboldt County near Alderpoint.

The river cuts in a northwesterly direction across Humboldt County, past a number of small mountain communities including Fort Seward. The South Fork Eel River joins from the west, near Humboldt Redwoods State Park and the town of Weott. Below the South Fork the Eel flows through a wider agricultural valley, past Scotia and Rio Dell, before receiving the Van Duzen River from the east. At Fortuna, the river turns west across the coastal plain and enters the Pacific via a large estuary in central Humboldt County, about 15 miles (24 km) south of Eureka.[11]

The Northwestern Pacific Railroad tracks follow the Eel River from Outlet Creek, about 7 miles (11 km) above Dos Rios, to Fortuna. The railroad has been out of service since 1998 due to concerns of flooding damage. U.S. Route 101 runs along the South Fork Eel River and then the lower Eel River below the South Fork.

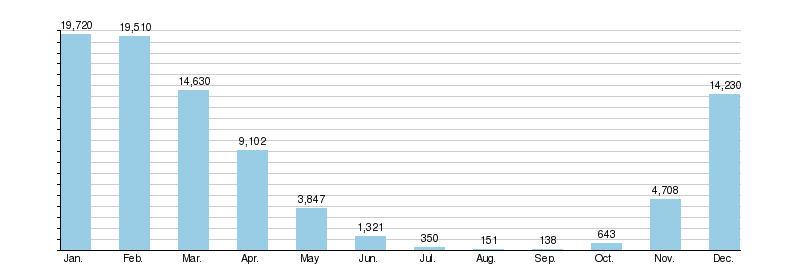

Discharge

Average flow of the Eel River varies widely due to its location, which places it more or less directly in the path of Pineapple Express-type winter storms. In the Mediterranean climate of its basin, almost all precipitation falls in the winter and wet season flows can be enormous, while the summer and early autumn provide only minimal precipitation, if any, allowing the sometimes mighty river to slow to a trickle. At the mouth, the Eel River produces an estimated annual runoff of 6.9 million acre feet (8.5 km3) per year, or about 9,500 cu ft/s (270 m3/s).[4] The Eel's maximum recorded flow of 936,000 cu ft/s (26,500 m3/s) on December 23, 1964 was the largest peak discharge of any California river in recorded history, and one of the largest peaks recorded in the world relative to the size of its drainage basin. In contrast, during the dry months of July through September, the river achieves nearly zero flow.[4]

The lowermost United States Geological Survey (USGS) streamgage on the Eel where flow volume is measured is at Scotia, where an annual mean of 7,309 cubic feet per second (207.0 m3/s), or 5.3 million acre feet (6.5 km3) per year, was recorded between 1910 and 2012. This station measures runoff from an area of 3,113 square miles (8,060 km2), or 85 percent of the basin; however it does not include the flow of the Van Duzen River, which joins several miles downstream.[7] Monthly average flows at Scotia range from 19,700 cu ft/s (560 m3/s) in January to 138 cu ft/s (3.9 m3/s) in September – a 143:1 difference. The annual means also experience huge variations, with a high of 12.5 million acre feet (15.4 km3), or 17,300 cu ft/s (490 m3/s), in 1983, and a low of 410,000 acre feet (0.51 km3), or 563 cu ft/s (15.9 m3/s), in 1977.[7]

Reduction in flow occurs in part due to deliberate water diversion from the Eel to the Russian River watershed by the Pacific Gas and Electric Company's Potter Valley Project, located to the south in Mendocino County. Although the effect on the total annual flow is negligible (only about 3 percent of the total flow of the Eel River) the impact is much larger during the dry season, when the Eel's already low natural flows are further reduced by diversions. Since 2004 the dams used by the project have been used to provide additional flow to the Eel River during the dry season, primarily to support fish populations.

Eel River monthly mean discharge at Scotia (cfs)[7]

Watershed

The Eel River drains an area of 3,684 square miles (9,540 km2), the third largest watershed entirely in California, after those of the San Joaquin River and the Salinas River. The Colorado, Sacramento, and Klamath River systems are larger, but their drainage areas extend into neighboring states as well. The Eel River system extends into five California counties – Glenn, Humboldt, Lake, Mendocino, and Trinity. The main stem traverses four counties, excepting Glenn. The majority of the watershed is located within Mendocino and Humboldt Counties.

The Eel's major tributaries – the North Fork, Middle Fork, South Fork and Van Duzen Rivers, drain 286 square miles (740 km2), 753 square miles (1,950 km2), 689 square miles (1,780 km2), and 420 square miles (1,100 km2), respectively.[10] The Middle Fork drains the greatest area of all the tributaries, but the South Fork is longer, and carries the most water because of the higher rainfall in its basin.

The Eel River watershed is located entirely in the California Coast Ranges. The topography creates a general drainage pattern that runs from southeast to northwest, except in the Middle Fork basin and the Eel headwaters, where water runs from east to west. The watershed is bordered on the north by the basin of the Mad River, on the east by that of the Sacramento River, on the west by that of the Mattole River, and on the south by those of the Russian River and Ten Mile River. Major centers of population on the river include Willits, Garberville, Redway, Scotia, Rio Dell, Fortuna, and Ferndale. Minor communities include Laytonville, Branscomb, Cummings, Leggett, Piercey, Benbow, Phillipsville, Myers Flat, Shively, and Pepperwood. The river's relatively large estuary and delta, which includes the Salt River tributary and related creeks, is located just one low ridge south from Humboldt Bay and 12 miles (19 km) south of Eureka, the main city for the entire region.[12]

Since the 19th century, logging activity in the watershed has loosened soil and destabilized aquifers, reducing the river's base flow, although the watershed is slowly recovering. Logging, grazing and other resource exploitation activities and their accompanying environmental changes have also increased the intensity of flood and drought.[13][14] Prior to 2011, the Eel River basin consisted of 65.1% forest, 12.2% shrubland, and 19.2% grassland, with just 1.9% agricultural and 0.2% developed urban. The human population of the watershed is about 32,000 – less than 10 people per square mile (26/km2).[15]:586

In the 20th century, much of the watershed area was included under state parks and national forest, including Six Rivers National Forest, Yolla Bolly-Middle Eel Wilderness, and Humboldt Redwoods State Park. A total of 398 miles (641 km) of the Eel River and its major tributaries are protected under the National Wild and Scenic Rivers system, with 97 miles (156 km) classed as Wild, 28 miles (45 km) as Scenic, and 273 miles (439 km) as Recreational. About 155 miles (249 km) of the main stem are designated, from the mouth to a point just below Cape Horn Dam. The Middle Fork is also Wild and Scenic from its confluence with the Eel to the boundary of the Yolla Bolly–Middle Eel Wilderness. The South Fork is designated from its mouth to the Section Four Creek confluence, the North Fork from its mouth to Old Gilman Ranch, and the Van Duzen River from its mouth to Dinsmore Bridge.[16]

Geology

Most of the Eel River watershed is underlain by sedimentary rock of the Franciscan Assemblage (or Complex), whose rocks date back to the Late Jurassic (161–146 million years ago).[17] The Franciscan is part of a terrane, or crustal fragment, that originated at the bottom of the Pacific Ocean. Beginning several million years ago, tectonic forces shoved the Franciscan assemblage against the North American Plate, pushing up the Coast Ranges.[18] The Eel River basin is among the most seismically active areas in California, especially in the north (the river empties into the Pacific only several miles north of Cape Mendocino near the Mendocino Triple Junction, which marks the northern end of the San Andreas Fault and produces frequent earthquakes due to the juncture here of three tectonic plates).[19] In the western and northern portions of the Eel River watershed, soils eroded from the Franciscan assemblage are often sticky, clayey and highly unstable, creating a high risk of landslides.[18] This soil is often known as "blue goo" because of its gray-blue texture and its tendency to slip when saturated.[20] Further inland and south, soils are well drained, although landslides are nevertheless common because of the high rainfall and steep slopes.[18]

Because of the mountainous topography, the only flat land in the Eel River watershed is along the larger river valleys, where stream terraces have been formed, and in the estuary region near the mouth of the river. Terraces were formed due to a combination of the high sediment load of the river system, and the rapid regional rate of geologic uplift (up to 13 feet (4.0 m) per 1000 years, as measured at Scotia Bluffs). The Eel's behavior of down cutting its own sediments has caused it to flow in a deeply incised channel, which can generally contain all but the largest floods.[14] The younger mountains in the north may be uplifting at a rate ten times faster than the headwater regions further south and east, which consist of much older rock.

The Eel River has the highest per-unit-area sediment yield of any river of comparable watershed size in the continental U.S., excluding those fed by active glacial or volcanic sources.[14] The estimated annual sediment load is 16 million short tons, or an average of 4,458 tons per square mile (1,720 tons/km2).[4] Flooding events have a large effect on the average amount of transported sediment: high water in the years 1969, 1983 and 1998 caused an annual sediment load 27 times greater than that of normal years.[21] Among rivers of the contiguous United States, only the Mississippi River carries more sediment to the sea[21] (the Colorado River historically transported more than the Eel as well, but most of its sediment is now trapped by dams). However, both the Mississippi and Colorado have lesser sediment yields relative to their drainage areas.

History

Native Americans

The Eel River basin has been inhabited by humans for thousands of years; some of the oldest concrete evidence of human habitation is at a petroglyph site near the upper Eel River discovered in 1913, which may be as old as 2500 years.[22] When the first European explorers arrived, the area was home to several tribes of the Eel River Athapaskan group, with at least four groups identified by dialects: Nongatl and Sinkyone in the north, and Lassik and Wailaki in the middle and south parts of the basin.[23]

European arrival

The first westerner to enter the Eel River was Sebastián Vizcaíno, sailing on behalf of Philip III of Spain, seeking a mythical northwest passage described in secret papers as being at the latitude of Cape Mendocino. Vizcaíno sailed into the mouth of the Eel in January 1603 where instead of the cultured city of Quivera the papers had described, the men encountered native people they described as "uncultured."[24]:170–171

Settlement in the 19th century

The Eel River was named in 1850 during the California Gold Rush by an exploring party led by Josiah Gregg.[8]:75–94 Except for Gregg who was a physician, naturalist and explorer, the remainder of the party were miners from a temporary camp on the Trinity River at Helena. The party took months to travel overland by less than favorable routes from Helena to the Pacific Ocean between November 1849 to December 1850 when they are credited with the rediscovery of Humboldt Bay by land. The bay had been seen by earlier Spanish and Russian explorers but never settled. After camping and restocking at Humboldt Bay, they traveled to San Francisco to report their discovery. They crossed the Eel River on their way south where they traded a broken frying pan to the local fishermen in exchange for a large number of Pacific lamprey, which they mistook for eels.[8]:75–94 They named the Van Duzen River after James Van Duzen, a member of the expedition. The party split in two and the survivors returned to San Francisco from where ships left to settle Humboldt Bay in early 1850, bringing lumber and supplies from San Francisco. One ship sailed up the Eel River and could not get out. In the hurry to be "first" in Humboldt Bay, they dragged a longboat through the sloughs on the north side of the Eel River mouth to the waters of the Bay where they were met by members of the Laura Virginia party.[8]:51

Many of the people who settled in this region were prospectors from the Gold Rush who did not manage to find gold. Although most of the early settlements were made along the coast, some people spread south into the Eel River valley, which offered fertile soils along with other abundant natural resources. However, the settlers also faced conflict as they pushed deeper into Native American lands. American negotiator Colonel Reddick McKee's treaty would have given the Indians a large reservation around the mouth of the Eel, but the treaties were never ratified.[25]:916[26] American settlements were made along the flat terraces of the Eel, near the confluence with the Van Duzen River and toward the mouth of the river where there was more arable land than the steep upper canyons. Most of these areas were appropriated for agriculture and grazing land. Salmon canneries flourished on the lower Eel between the 1870s and the 1920s, and declined thereafter because of decreasing runs caused by overfishing and other manmade environmental changes. Logging companies also took hundreds of millions of board feet of timber from the basin, which were floated down the Eel River to the estuary. Because the Eel River's twists and turns made it difficult to float the large redwood logs, the timber was cut into smaller rectangular "cants" to make them more manageable.[27]:28 In 1884 the Eel River and Eureka Railroad began shipping lumber from the Eel River estuary to the port at Humboldt Bay, where the logs were loaded onto ships bound for San Francisco.[28]

20th century

As part of the Potter Valley or Eel River Project, a pair of dams were built across the upper reaches of the Eel beginning in 1906 to divert water to the much more populous but smaller Russian River drainage area to the south, resulting in a much higher flow in the smaller river and a significantly decreased flow in the upper Eel during certain seasons.[29] Although located near the headwaters, these dams can cause a significant reduction of the flow of the lower Eel River because much of the river's summer flow originates from the mountains above Lake Pillsbury.

In 1911 noted American engineer John B. Leonard designed Fernbridge, a 1,320 feet (400 m) all concrete arched bridge at the site of an earlier ferry crossing.[30] Now listed on the National Historic Register, Fernbridge is the last major crossing before the Eel arrives at the Pacific Ocean.[31] The last crossing before the Pacific Ocean is at Cock Robin Island Road a few miles to the west of Fernbridge. Later, the Pacific Coast Highway would be constructed along the South Fork and along the Eel River downriver of the South Fork.

In 1914, after seven years of construction, the Northwestern Pacific Railroad completed a rail line running along much of the Eel River as an important transportation link connecting Eureka and the many small towns along the Eel River valley to the national rail network. The railroad had the ignominious distinction of being the most expensive (per mile) ever built at the time: it traversed some of the most rugged and unstable topography in California, with 30 tunnels in a 95-mile (153 km) stretch. The ceremonial driving of the golden spike was delayed by flooding and subsequent landslide damage to the rail line in October 1914.[32]

In the 1950s, interest grew in damming the Eel River system to provide water for Central and Southern California. After damaging floods in 1955, these dams also received support for potential flood-control benefits. The U.S. Bureau of Reclamation and U.S. Army Corps of Engineers proposed a series of dams on the river and its tributaries, the largest of which was the enormous Dos Rios Dam near the confluence with the Middle Fork, which would provide water for the California State Water Project and control flooding.[33] Water would be diverted through a 40-mile (64 km) tunnel to the Sacramento Valley, where it would join the water flowing down the Sacramento River to the California Aqueduct pumps in the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta. The proposal was defeated with public initiative by the early 1970s, to protect the remaining relatively wild rivers in the state.[33] Ronald Reagan, governor of California at the time, refused to approve the project. The proposed reservoir would have flooded the Round Valley Indian Reservation.[34]:199

In 1964, a severe Pineapple Express event, known as the Christmas flood of 1964, brought heavy rains to coastal northern California.[35] The Eel River drainage area was directly in the storm's path. With no major dams to control its flow, the main Eel reached a peak of 936,000 cu ft/s (26,500 m3/s), with 200,000 cu ft/s (5,700 m3/s) from the South Fork alone. Ten towns were obliterated with dozens of others damaged; at least 20 bridges were destroyed, and some, including Miranda and South Fork, were never rebuilt.[35] The heavy damage was due not only to the water, but to the huge amount of sediment and debris swept down the river, including millions of board feet of timber. The deepest flood waters were nearly 70 feet (21 m) above the normal river level. Several thousand people were left homeless by the floods and over 4,000 head of livestock died.[35]

The large storms of the mid-20th century, along with the ecological changes from logging and grazing activities, almost wiped out the river's salmon run. Due to huge earth-flows caused by the record rain in 1964, 105 million tons of sediment were carried down the Eel River between December 21–23 as measured at Scotia – more than in the previous eight years combined. This sediment scoured away or buried spawning grounds for salmon and steelhead trout, causing the populations of these fish to drop to dangerous levels by the mid-1970s.[6]

The flooding was also deleterious to rail service through the Eel River canyon. After the 1964 floods, much of the topography in the Eel River drainage has been permanently damaged, and landslides occur much more often, frequently damaging local road and rail infrastructure. In 1998, after another large flood in the winter of 1996–1997 washed out sections of the line, the Northwestern Pacific became the first railroad to be shut down by the federal government for safety reasons. Although the portion south of Willits was reopened in 2006, the section between Willits and Samoa, which includes the entire Eel River portion of the tracks, is unlikely to ever be returned to service.[36]

Ecology

Plants

The Eel River watershed lies within the Oregon and Northern California Coastal freshwater ecoregion, which is characterized by temperate coniferous forests consisting largely of Douglas fir and western hemlock.[37] The watershed also contains many stands of Redwood that are among the largest such trees in California. In the Eel River basin, redwoods can be found further inland than other parts of the northern California coast because of the wide lower valley of the river, which acts like a funnel conducting moist air eastwards from the coast. However, redwood groves are still most common in the drainage area of the South Fork Eel River, which lies closest to the Pacific.[38]

Animals

Aquatic mammals include beaver, muskrat, raccoon, river otter and mink.[15]:586 Beavers are confirmed in Outlet Creek (tributary to main stem Eel north of Willits), but may occur in other areas as well.[39] That beaver were once native to the Eel River watershed is supported by the name of a tributary of the Middle Fork Eel River, Beaver Creek.[40]

Salmon and steelhead

The Eel River supports runs of multiple anadromous fishes – Chinook, coho salmon, steelhead (rainbow trout) and coastal cutthroat trout among the major species. In its natural state, it was the third largest salmon and steelhead producing river system in California – with over a million fish spawning annually – after the Sacramento and Klamath rivers. The annual chinook salmon run was estimated at 100,000–800,000, coho at 50,000–100,000, and steelhead may have numbered as high as 100,000–150,000.[14]

About 22,000 years ago, a massive landslide off Nefus Peak dammed the Eel River near Alderpoint to a height of 460 feet (140 m). A 30-mile (48 km)-long lake formed behind the barrier. Sediment deposits indicate the lake may have persisted for as many as several thousand years, which is highly unusual considering the easily eroded rock of the region and the highly unstable nature of landslide dams in general.[41] The dam blocked access to steelhead trout spawning grounds in the upper Eel River, causing the summer and winter runs to interbreed. Thus, there is an unusually high genetic similarity between summer-run and winter-run steelhead in the Eel River system, in contrast to other rivers in the Western United States.[42][43]

Human impacts have led to a dramatic decline of salmon and steelhead populations in the Eel River system. Large-scale commercial fishing began in the 1850s, with multiple canneries on the Eel River operating into the early to mid 1900s. Between 1857 and 1921, canning operations took an estimated 93,000 fish per year, with a peak of 600,000 fish in 1877.[14] By the 1890s, fish populations had already recorded a precipitous decline.[44] Logging and grazing, which expose formerly forested land as bare ground, have had even greater impact on the populations of these fish. Due to the mountainous terrain and heavy precipitation in the Eel River watershed, erosion rates are particularly high.[45] Much of the anadromous fish spawning habitat in the river system was covered by sediment or blocked by debris jams. Record flooding in 1955 and 1964, which destroyed or damaged large amounts of habitat along the Eel and its tributaries, was generally regarded as the final blow.[14] After the Christmas flood of 1964, chinook salmon populations plunged to less than 10,000 per year.[14]

Anadromous fish populations have continued to decline since the 1960s; in 2010, only 3,500 salmon and steelhead returned to the river to spawn.[14] However, with better land management practices in the watershed, salmon and steelhead runs have shown signs of recovery. In late 2012, high water in the Eel River attracted a run of over 30,000 fish, the largest on record since 1958.[46]

Other fishes

The river provides wildlife habitat for preservation of rare and endangered species including warm and cold freshwater habitat for fish migration and spawning.[6] The river and its tributaries support at least 15 species of native freshwater fish. Major species include Pacific lamprey, Entosphenus tridentatus, formerly Lampetra tridentata, Sacramento sucker, threespine stickleback, Pacific staghorn sculpin, Coastrange sculpin and prickly sculpin.[15] At least 16 species of non-native fish have been introduced to the river system.[47] The non-native Sacramento pikeminnow is present; it competes with and preys on young salmonids.[14][48]

The Eel River has never contained true eels, but is named for the Pacific lamprey, an eel-shaped parasite that attaches itself to other fish during its ocean life-cycle. Like salmon and steelhead, lampreys are anadromous, meaning they live part of their life in the ocean but return to fresh water to spawn. They are Cyclostomes (Circle mouths), a primitive fish-like creature, and are not related to eels.[49]

Eel River estuary

The Eel River forms a 7-mile (11 km) long estuary west of Fortuna, which has been identified as one of the most important and sensitive estuaries on the West Coast. The estuary consists of some 8,700 acres (3,500 ha) of tidal flats, perennial and seasonal wetlands, connected by 75 miles (121 km) of river channels and tidal sloughs.[50] About 1,550 acres (630 ha) consist of undeveloped wetlands while 5,500 acres (2,200 ha) have been converted to agriculture.[51] The estuary is the third largest coastal wetland region in California, after the Sacramento–San Joaquin River Delta and the Salinas River estuary in central California, forming an important habitat for various species of shorebirds, fish and mammals such as river otters and harbor seals.[51] About 1,100 acres (450 ha) of the estuary are protected as the Eel River Estuary Preserve.[52]

The Eel River estuary is recognized for protection by the California Bays and Estuaries Policy.[53]

River modifications

There are two hydroelectric dams on the Eel – 130-foot (40 m) Scott Dam, which forms Lake Pillsbury, and 50-foot (15 m) Cape Horn Dam, which forms Van Arsdale Reservoir just north of Potter Valley. At Cape Horn Dam, the majority of the water is diverted through a tunnel and hydroelectric plant, and then to the headwaters of the Russian River in Potter Valley and is known as the Potter Valley Project. Originally conceived in the late 1800s and built between 1906 and 1922, the project provides about 159,000 acre feet (0.196 km3) of additional waters for the Russian River system, for about 500,000 people in Mendocino and Sonoma Counties.[54]

The Potter Valley Project has been argued by environmental groups to have significant impacts on the salmonid (Chinook and coho salmon and steelhead) populations of the basin.[55] Although dam operators are required to maintain certain flows below the diversion during the dry season, these flows can be cut during exceptionally dry years, preventing salmonids from reaching certain spawning streams in the Eel River basin.[56] Project water is disproportionately important to salmonids in the Eel River system as a whole because the water released from the bottom of Scott Dam is the only cold water available in the basin during the dry season. During July, August and September, temperatures in the lower Eel River occasionally hit 85 °F (29 °C) or higher, creating fatal conditions for these fish.

In 1983, the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission relicensed the project under the condition that more water be provided to the Eel River during the dry season and less be diverted to the Russian River basin. Dam releases are now timed to mimic natural flows in the Eel River system. Occasional large "blocks" of water are also released from Scott Dam to help juvenile salmonids migrate to the sea before temperatures in the lower river become unsuitable for their passage.[57] These conditions were revised in 2004, when stricter minimum release standards were established. In combination with drought in the early 21st century, average diversions through the project have decreased by about 69,000 acre feet (0.085 km3) for the period 2004 through 2010.[58] In December 2013, due to record low levels of water in the Eel River and the associated dammed lakes, levels of fish and lampreys in the rivers were at lowest recorded levels, and Pacific Gas and Electric Company sought to have FERC change their operating license to permit even lower releases of water to Eel until the drought eases.[57] Under current agreements, the dams must release at least 100 cubic feet per second (2.8 m3/s) beginning every year on December 1 to aid salmon migration.[57]

The federal United Western Investigation study in 1951 proposed multiple large dams on the wild North Coast rivers of California, including the Eel River. These dams would have been far bigger than those of the Potter Valley Project, and would create some of the largest reservoirs in California. The Army Corps of Engineers and Bureau of Reclamation both sought to build dams in the Eel River system, which starting in the 1960s was targeted as a potential new source for the California State Water Project.[59]:272 Major dams proposed in the watershed included ones at English Ridge, Bell Springs and Sequoia (Alderpoint) on the main stem, and the infamous Dos Rios on the Middle Fork. Dos Rios Dam would have flooded 110,000 acres (45,000 ha) of Mendocino County, creating a reservoir of 7.5 million acre feet (9.3 km3) – the largest in California, at nearly twice the size of Shasta Lake.[33]:136

Water would have been diverted from English Ridge north to Dos Rios and through a 40-mile (64 km) tunnel to the offstream Glenn-Colusa reservoir in the Sacramento Valley, from which the water would travel by canal to the Sacramento River. An alternate proposal would have sent the water south from Dos Rios, through English Ridge and then a tunnel to Clear Lake, from which the water would flow down Cache Creek to the Sacramento River.[33]:147 From the beginning, these dams were heavily contested by local residents as well as by environmental groups seeking the protection of California's remaining wild rivers.

The floods of 1955 and 1964 brought renewed interest in building large dams on the Eel River, especially in the case of the Army Corps of Engineers, which attempted to justify the construction of Dos Rios for flood control. However, among all the proposed dams on the Eel River, Dos Rios would have the lowest impact on flood control – a fact that the Army Corps took great pains to conceal, by greatly exaggerating its economic justifications for the dam.[33]:146 When exposed, this would end up becoming the "Achilles' heel of the project".[60] Meanwhile, the Bureau insisted that its first priority – English Ridge – should receive the first federal funding. As Marc Reisner describes in Cadillac Desert (1986), "the feuding agencies were about to lock horns and starve over the first two dams on their priority list". By 1969, a strong opposition movement had formed, led by a Round Valley rancher named Richard Wilson, who had studied hydraulics at Dartmouth College. Wilson calculated that Dos Rios would have reduced the 35-foot (11 m) flood crest of the 1964 flood at Fort Seward by less than a foot (0.3 m).[34]:194 Governor Ronald Reagan formally refused to authorize the project.[61]

Despite Reagan's veto, the door to Eel River dams technically remained open. In early 1972, California state senator Peter H. Behr introduced a measure to create a state wild and scenic rivers system, which would protect many undeveloped North Coast rivers, including the Eel, from future damming. In the same year, senator Randolph Collier proposed a measure that would block dams in the Klamath and Trinity Rivers but "permitted 'planning' for dams on the Eel River. Conservationists saw this as a backdoor attempt to resurrect Dos Rios Dam and endorsed the Behr bill."[62]:313 Collier's bill was supported by powerful agricultural interests in the Central Valley on the "dubious claim" that they would need the water of these rivers in the future. After the state legislature approved both bills, the final decision fell to Reagan, who signed the Behr bill, again in favor of the conservationists. However, Behr had been forced to compromise in order to get his bill approved from the state: as signed, it would only place a 12-year moratorium on planning for dams in the Eel River system.[62]:315

Over the next several years, Reagan continued lobbying for increased protection of the Eel River system. In 1979, he requested the North Coast rivers be added to the National Wild and Scenic system. In 1981 – well before Behr's moratorium expired – Secretary of the Interior Cecil Andrus granted federal protection to the Eel River system and 1,235 miles (1,988 km) of streams along the North Coast, succeeding state legislation and placing the river permanently off limits to new dams.[63]:175

Recreation

The four forks of the Eel and their tributaries provide many opportunities for whitewater kayaking and rafting on their upper sections. There is a 12-mile (19 km) class IV–V run between the Scott and Van Arsdale dams. A popular run is from Dos Rios to Alderpoint with Class II–III rapids, taking three to four days to run, depending on how many side tributaries are explored. From Alderpoint to Eel Rock is a class I–II float during June, with many beaches suitable for camping. Below Eel Rock the ocean winds make boating difficult starting in the early afternoon.[64]:134–135

The South Fork is a class III–IV run in its upper section between Branscomb and Cummings, with a waterfall that needs to be portaged. After the South Fork turns due north at Cummings it is mainly a class II–III, changing mostly to a class II run below Piercy. The Middle Eel has a good run from the confluence with the Black Butte River to Coal Miners Falls, which is portaged by all but experts. The Van Duzen River also has some class II–III runs beginning below Goat Rock. The North Fork is the most pristine of the tributaries, but is difficult to enter because of its remote location. There is a Class III run in the reach between Hulls Creek and Mina Road.[64]:135–137

There are also many miles of river suitable for flatwater boating in the downstream sections of both the mainstem Eel and the South Fork. Humboldt Redwoods State Park leads paddle trips along that stretch of the river.[65] There is good fishing for Chinook salmon and steelhead in the lower river, and rainbow trout are found above Lake Pillsbury. Introduced pikeminnow, in conjunction with the diminished flows due to the Potter Valley Project water diversion, have taken a significant toll on the native fish population below Van Arsdale Dam. The river can be closed to fishing in some years after October 1 if flows are insufficient for migrating salmon and steelhead.[66]:109–110

The Eel River watershed includes Admiral William Standley State Recreation Area, Smithe Redwoods State Recreation Area, Standish-Hickey State Recreation Area, Humboldt Redwoods State Park, Richardson Grove State Park, Six Rivers National Forest, and Mendocino National Forest, which are popular for camping and hiking.[67][68] There is wilderness camping above Lake Pillsbury on both branches, the Rice Fork and Eel River, (also known as South Eel because it is south of the lake), which have plenty of swimming holes and camp sites.[69]:47

See also

- List of rivers in California

- Benbow Lake State Recreation Area

- Eel River Athapaskans

- List of Eel River crossings (California)

- List of South Fork Eel River crossings

References

- "Eel River". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. 28 November 1980. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- Source elevation derived from Google Earth search using GNIS source coordinates.

- About the Eel River Archived 19 July 2007 at the Wayback Machine, Friends of the Eel River

- Lisle, Thomas E. "The Eel River, Northwestern California: High Sediment Yields from a Dynamic Landscape" (PDF). United States Forest Service. Retrieved 14 December 2013.

- "Basic Database Searching, cahtotext database". Retrieved 7 July 2012.

- William M. Brown and John R. Ritter, Sediment transport and Turbidity in the Eel River Basin Archived 24 December 2013 at the Wayback Machine, 1971, prepared in cooperation with the California Department of Water Resources, 67 pages

- "USGS Gage #11477000 on the Eel River at Scotia, CA" (PDF). National Water Information System. United States Geological Survey. 1910–2012. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Bledsoe, Anthony Jennings (1885). Indian Wars of the Northwest: A California Sketch. Bacon.

- Bright, William; Erwin G. Gudde (1998). 1500 California Place Names: Their Origin and Meaning. University of California Press. p. 51. ISBN 0-520-21271-1.

- "National Wild and Scenic Eel River", The Eel River Reporter, Friends of the Eel River publication Vol.VIII, Summer 2005 p.14

- California Road & Recreation Atlas (4th ed.). Benchmark Maps. 2005. ISBN 0-929591-80-1.

- Estuary Subbasin Overview, Coastal Watershed Assessment and Planning Program, 2013. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Summer Water Woes Require Responsible Use, June 3–18, 2013, Friends of the Eel River. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Yoshiyama, Ronald M.; Moyle, Peter B. (1 February 2010). "Historical Review of Eel River Anadromous Salmonids, With Emphasis on Chinook Salmon, Coho Salmon and Steelhead" (PDF). Center for Watershed Sciences. University of California Davis. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Benke, Arthur C.; Cushing, Colbert E. (2005). Rivers of North America. Academic Press. ISBN 0-12-088253-1.

- "Eel River, California". National Wild and Scenic Rivers System. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Ogle, Burdette A. (1953). Geology of Eel River Valley Area, Humboldt County, California. California Department of Natural Resources, Division of Mines.

- "Chapter 3.8: Geology and Soils" (PDF). Humboldt County General Plan. County of Humboldt. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- "Lower Eel River Basin Assessment". California Coastal Watershed Planning and Assessment Program. July 2010. Archived from the original on 17 November 2010. Retrieved 12 December 2013.

- Anderson, Leslie Scopes (2011). "Unearthing Evidence of Creatures from Deep Time: A Beginner's Fossil Guide to the Northern California Coast" (PDF). Humboldt State University. Retrieved 18 December 2013.

- Impediments to fluvial delivery to the coast Archived 23 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, California Beach Restoration Study, January 2002, 50 pages

- Foster, Daniel G.; Foster, John W. "Eel River Petroglyphs". California Department of Parks and Recreation. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- "Eel River Athabaskan". Survey of California and Other Indian Languages. University of California Berkeley. Retrieved 15 December 2013.

- Philip L. Fradkin (1995). The Seven States of California: A Natural and Human History. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20942-8.

- Hittell, Theodore Henry (1898). History of California, Volume 3, Book X, Chapter XII- Treatment of Indians (Continued). San Francisco,California: J. N. Stone. pp. 912–936. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Ray Raphael (1 January 1993). Little White Father: Redick McKee on the California Frontier. Humboldt County Historical Society. ISBN 978-1-883254-00-1.

- O'Hara, Susan J.P.; Stockton, Dave (2012). Humboldt Redwoods State Park. Images of America. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 0-73859-513-6.

- Borden, Stanley T. (1963). "Street Railways of Eureka". 27 (10, issue 297). The Western Railroader. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - PG&E’s Potter Valley Hydroelectric Project Archived 4 October 2013 at the Wayback Machine, Friends of the Eel, 2013. Retrieved 4 October 2013.

- NRHS. "National Register of Historic Places". U.S. Government. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- USGS. "United States Geological Survey". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- LeBaron, Gaye, Eel River rail line tough to build, and tough to kill, Santa Rosa Press Democrat, April 30, 2011, accessdate December 23, 2013

- Simon, Ted (6 September 1994). The River Stops Here: How One Man's Battle To Save His Valley Changed the Fate of California. Random House. p. 380. 978-0679428220. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Reisner, Marc (1993). Cadillac Desert. Penguin. ISBN 0-14-017824-4. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Lucia, Ellis (1965). Wild Water: The Story of the Far West's Great Christmas Week Floods. Portland, Oregon: Overland West Press. OCLC 2475714. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- Burns, Ryan, The disappearing railroad blues, North Coast Journal, May 16, 2013. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- "Oregon and Northern California Coastal". Freshwater Ecoregions of North America: A Conservation Assessment. Freshwater Ecoregions of the World. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- "Lower Eel River and Eel River Delta Watershed Analysis, Scotia, California – Cumulative Watershed Effects Assessment" (PDF). Mendocino Redwood Company and Humboldt Redwood Company. Retrieved 3 August 2013.

- Beaver Mapper, Riverbend Sciences, 2013

- "Beaver Creek". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey.

- Evidence of ancient lake in California's Eel River emerges, University of Oregon, Eugene, November 14, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Neith, Katie, Evidence of Ancient Lake in California's Eel River Emerges California Institute of Technology News, November 11, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Perkins, Sid, Ancient Landslide Merged Trout Populations, Science Now, November 14, 2011. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Van Kirk, Susie, ed. (1996). "Eel River Fisheries Articles and Excerpts 1891-1902". Klamath Resources Information System. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Trumble, Jessica. "Eel River Salmon Restoration Project". Information Center for the Environment. University of California Davis. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- "Eel River salmon run 'largest ever seen'". The Willits News. 7 November 2012. Retrieved 11 August 2013.

- Brown, L. R.; Moyle, P. B. (1997). "Invading species in the Eel River, California: Successes, failures, and relationships with resident species". Environmental Biology of Fishes. 49 (271–291).CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- "Ptychocheilus grandis (Sacramento pikeminnow)". NAS - Nonindingenous Aquatic Species. United States Geological Survey. Retrieved 18 December 2012.

- Wildlife Humboldt Redwoods State Park, 2013 Archived 3 February 2009 at the Wayback Machine

- "Eel River Estuary". Western Rivers Conservancy. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Chapter 4: The Eel River Planning Area". Humboldt County Planning Department – Local Coastal Program. County of Humboldt. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- "Eel River Estuary Preserve". The Wildlands Conservancy. 2012. Retrieved 20 April 2014.

- State Water Resources Control Board Water Quality Control Policy for the Enclosed Bays and Estuaries of California (1974) State of California

- "The Potter Valley Project". Potter Valley Irrigation District. Retrieved 23 December 2012.

- Driscoll, John (4 March 2010). "Conservation group challenges PG&E, seeks more water for Eel River". Times–Standard. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Graziani, Victoria (5 June 2013). "Eel River stakeholders hear history and concerns from Russian River side of diversion". Redwood Times. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Graziani, Virginia, PG&E seeks reduction in releases to Eel River due to drought, Redwood Times, December 10, 2013. Retrieved 25 December 2013.

- "How much of Eel River Water is diverted through the Potter Valley Project?". Potter Valley Irrigation District. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Seckler, David William (1971). California Water: A Study in Resource Management. University of California Press. ISBN 0-52001-884-2.

- Wilson, Richard (1969). "The Dos Rios Project" (PDF). The Wildlife Society, Western Section. Retrieved 23 December 2013.

- Dunning, Harrison C. "California Water: Will There Be Enough?" (PDF). Environs. University of California Davis. Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 December 2013. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- Cannon, Lou (2005). Governor Reagan: His Rise to Power. Ronald Reagan: A Life in Politics. PublicAffairs. ISBN 1-58648-284-X.

- Palmer, Tim (2004). Endangered Rivers and the Conservation Movement. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 0-74253-141-4.

- Palmer, Tim (1993). The Wild and Scenic Rivers of America. Island Press. ISBN 1-61091-368-X.

- Fishing in the Eel River Valley, 2013, Sunny Fortuna

- Stienstra, Tom (2012). Moon California Fishing: The Complete Guide to Fishing on Lakes, Streams, Rivers, and the Coast. Avalon Travel. ISBN 1-61238-166-9.

- "Eel River Watershed Management Area" (PDF). North Coast Regional Water Quality Control Board, Watershed Planning Chapter. California State Water Resources Control Board. Retrieved 24 December 2013.

- The National Map (Map). Cartography by USGS. United States Geological Survey. Archived from the original on 29 March 2012.

- McMahon, Richard (2001). Camping Northern California. Globe Pequot. ISBN 1-56044-895-4.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Eel River (California). |

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: South Fork Eel River, USGS, GNIS

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: North Fork Eel River, USGS, GNIS

- USGS Real Time Stream Data for

- Friends of the Eel River

- Map of the Eel River drainage basin

- Kubicek, P.F., Summer water temperature conditions in the Eel River System, with reference to trout and salmon, M.S. Thesis, Humboldt State University, Arcata, California. August 1977. 200 p.

- Eel Wild and Scenic River - BLM page