Salinas River (California)

The Salinas River is the longest river of the Central Coast region of California, running 175 miles (282 km) and draining 4,160 square miles.[6] It flows north-northwest and drains the Salinas Valley that slices through the central California Coast Ranges south of Monterey Bay.[3] The river begins in southern San Luis Obispo County, originating in the Los Machos Hills of the Los Padres National Forest. From there, the river flows north into Monterey County, eventually making its way to connect with the Monterey Bay, part of the Pacific Ocean, approximately 5 miles south of Moss Landing. The river is a wildlife corridor, and provides the principal source of water from its reservoirs and tributaries for the farms and vineyards of the valley.

| Salinas River | |

|---|---|

View of the Salinas River near San Ardo in May 2008. During the rainier winter months, the river may occasionally reconnect with Monterey Bay. The San Ardo Oil Field is visible in the distance. | |

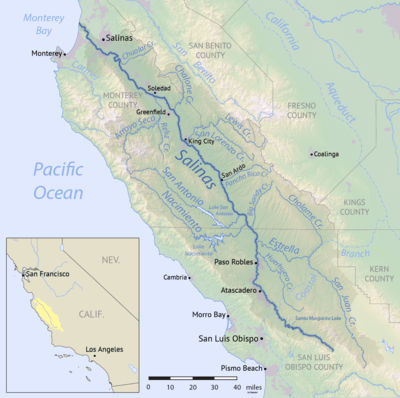

Map of the Salinas River watershed | |

| Location | |

| Country | United States |

| State | California |

| Cities | Paso Robles, Soledad, Salinas |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Source | Los Machos Hills in the Los Padres National Forest |

| • location | San Luis Obispo County, California |

| • coordinates | 35°12′57.2394″N 120°13′26.112″W[3] |

| • elevation | 2,150 ft (660 m) |

| Mouth | Monterey Bay |

• location | 6 miles north of Marina, California |

• coordinates | 36°44′58″N 121°48′13″W[3] |

• elevation | 0 ft (0 m) |

| Length | 175 mi (282 km)[5] |

| Basin size | 4,160 sq mi (10,800 km2) |

| Discharge | |

| • location | near Spreckels |

| • average | 421 cu ft/s (11.9 m3/s) |

| • minimum | 0 cu ft/s (0 m3/s) |

| • maximum | 95,000 cu ft/s (2,700 m3/s) |

| Basin features | |

| Tributaries | |

| • left | Nacimiento River, San Antonio River, Arroyo Seco |

| • right | Estrella River, San Lorenzo Creek |

Salinas River |

|---|

Until recently, the Salinas River had a continuous flow throughout the year, stretching back to at least 1941—when United States Geological Survey (USGS) began complete monitoring records in the Salinas area—through 1989. Most probably primarily due to recent increases in agricultural water demand in the Salinas Valley, and the resultant lowering of water tables, the lower reaches of the Salinas river (north of King City) remained entirely dry during the three years 2013–2016.[7]

The atypical drought-breaking rains of the winter of 2016–2017 restored the river's flow to its lower northern reaches in January 2017.

Hydrology

In 1769 when the river was first discovered by non-Native peoples via the Portola expedition, it was reported by them as being a "river watering a luxuriant plain" filled with fish weighing 8 to 10 pounds (3.6 to 4.5 kg).[8] As of the end of 2016, the river had been transformed into little more than a dry bedded run-off feature for the majority of its length.

Nonetheless, with sufficiently heavy rains, and on rare occasions, this now normally dry runoff feature is still capable of quickly transforming itself back into a fast flowing river. In rainfall induced flood conditions, it can at times measure over a mile in width. During the 20th century, such flood conditions are reported to have generally occurred approximately once every 3 to 10 years. The last similar flooding event along the river was reported in 1998.[9]

The current most typical dry or zero flow state of the majority of the river may be more the result of human activity than of any recent changes in weather patterns. Rainfall patterns of recent years in the Salinas area have not significantly changed from historical average rainfall patterns; the 139-year average annual rainfall in Salinas is 13.26 inches (337 mm) per year, and the average annual rainfall since 2000 is 11.01 inches (280 mm) per year.[10][11] Recent increases in water use, primarily in the agricultural sector, and the damming of the river and its tributaries may be contributing factors causing the now mostly dry condition of the riverbed.[12]

The Monterey County Water Resources Agency currently operates a water usage monitoring program which requires that all agricultural water users self-report annually on the estimated amount of groundwater pumped from the shrinking Salinas Valley aquifer.[13][14] This is in contrast to some areas of the country where various water authorities both monitor, and also regulate water usage by agricultural water users.[15]

The previous ecosystem of the Salinas River, which once included steelhead trout, and numerous other species throughout the full length of a once year-round flowing river, has clearly been drastically impacted in recent years by the expanding heavy demands of agricultural water use in the Salinas Valley, and the resulting most typical dry-river conditions.[16]

History

The ancient geological history of the Salinas River is currently held by tectonic plate theory to most probably be rather unique amongst the many rivers of the North American Western Seaboard. The discovery of the great submarine canyon at the mouth of the Salinas River, the Monterey Canyon is the primary basis for this theory of what is now held to be the most probable and singular ancient geological history for the Salinas River.[17]

The uniquely long and deep submarine Monterey Canyon, located at the mouth of the Salinas River dwarfs all other such canyons along the Pacific edge of the North American continent. Still, the known flow-properties of the Salinas River in no way seem to indicate a river capable of creating such a large submarine outflow canyon. For these reasons it is now theorized that at one point, probably many millions of years ago in the Miocene epoch, due to tectonic plate drift as currently calculated, the river was then most probably located in the vicinity of what is now current day Los Angeles, and at that time may have served as the ancient mouth of the then Colorado River.[17]

The Salinas River is also thought to have drained prehistoric Lake Corcoran, which once occupied much of what is now California's Central Valley about 700,000 years ago, prior to the valley developing an outlet via the Carquinez Strait into what is now San Francisco Bay.[18]

At the time of man's first appearance along the California coast approximately 13,000 years ago, during the latter part of the Pleistocene epoch, and on up until the age of the European discovery and exploration of Alta California, the Salinan Indians and the Esselen Indians, and their ancestors lived along the Salinas river, and in the adjacent Salinas valley.

The Salinas river was first sighted by Europeans on September 27, 1769. This first European contact with the river was recorded by the Spanish "colonizing expedition" of Gaspar de Portolà. As was the practice of the Spanish government in the New World at the time, soldiers and priests were then typically sent out on such colonizing expeditions. Accordingly, the Portolá expedition included Franciscan priests, who soon thereafter established two missions along the banks of the Salinas river (then referred to as el Rio de Monterey.)

The new missions built along the banks of the Salinas river were the Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad established in 1791, and the Mission San Miguel Arcángel, established in 1797. The Mission San Antonio de Padua was also established during this same time period in the Salinas valley, but not on the river itself. These three missions were a part of the chain of 21 missions, then commissioned by the Spanish government in what is now the American State of California. All three of these missions remain to this day, the Soledad mission having evolved into the city of Soledad, and the San Miguel mission having evolved into the unincorporated village of San Miguel. The San Antonio mission is now surrounded by Fort Hunter Liggett land.

As a result of the 1906 San Francisco earthquake, the river mouth at Monterey Bay was diverted 6 miles south from an area between Moss Landing and Watsonville to a new channel just north of Marina.[19]

The historic increase in agriculture and settlement in the area, and the related increased water consumption demands have had a significant impact on the Salinas River. The river now typically remains dry and/ or without flow for the majority of the year, and downstream (North) of King City remained fully dry or with zero flow during the years 2013 - 2016.[7][20] Still the river has occasionally had notable flooding. Amongst these notable floods were the flood of 1964,[21] and the flood of 1995.[22]

Naming

During the Spanish/ Mexican period, the river was named "El Rio de Monterey". Soon after the American annexation of the area, it was renamed as the Salinas River. When first encountered by the Spanish Portola Expedition on September 27, 1769, the members of the expedition at first suspected that they had found the Carmel River, as discovered earlier by Vizcaíno. One of the party members, Father Crespi, then proposed that the river might be a different river, and that it should therefore be given a new name, however he appears to have been over-ruled by the other members of his party at the time.

The first agreed upon name for the river, as it subsequently appeared on many Spanish and Mexican maps, was Rio de Monterey, presumably being named after the newly founded nearby town of Monterey. The earliest recorded use of this name for the river was a reference made by Fr. Pedro Font on March 4, 1776. This name continued in use as late as 1850.[1]

The river was apparently renamed as the "Salinas" river by an American cartographer in 1858, ten years after the 1848 American acquisition of California from Mexico. In 1858 the newer "Salinas" name first appeared on an American made map as the Rio Salinas, most probably so renamed after the nearby American founded town of Salinas, which in turn appears to have first been named in 1854 after the old Rancho Las Salinas land grant, parts of which included the later city of Salinas.[23]

Description

The river begins in southern San Luis Obispo County, approximately 2.5 miles east of the summit point of Pine Ridge,[24] at a point just off of Agua Escondido Road, coming down off of the slopes of the Los Machos Hills of the Los Padres National Forest.[25][26] The only dam situated directly on the Salinas River (the Salinas Dam) forms the small Santa Margarita Reservoir. The Salinas flows down the valley bounded on its southwestern side by the Santa Lucia Mountain Range, and bounded on its northeastern side by the Gabilan Mountain Range. It flows past Atascadero and Paso Robles (to Monterey). It receives the natural outflow of the Estrella River and the controlled outflows of the Nacimiento and San Antonio reservoirs through their respective river tributaries in southern Monterey County.

The river passes through the active San Ardo Oil Field, and then into and through the Salinas Valley. It flows past many small towns in the valley, including: King City, Greenfield, and Soledad, where it combines with the flash-flood prone Arroyo Seco.

It flows 3 miles south of the city of Salinas before cutting through Fort Ord and flows into central Monterey Bay approximately 3 miles west of Castroville. The final stretch of the river forms a lagoon protected by the 367 acre Salinas River National Wildlife Refuge and its outflow to Monterey Bay is blocked by sand dunes except during winter high-water flows.

- Historical course

The land owners altered the course of the river by filling in the river bed during the dry season. This allowed them to farm all of their land and use the water as they saw fit. The old stream bed went from the Old Salinas River, joining Elkhorn Slough on Monterey Bay near Moss Landing, to the present course where the main channel's mouth is directly on the Pacific Ocean. The Old Salinas River channel that diverts north behind the sand dunes along the ocean, is used as an overflow channel during the rainy season.

Ecology

Before the arrival of Hispanic and American settlers in the area, the Salinas river was once the home of abundant fish and beaver populations.

Regarding historical fish populations, the Arroyo Seco is the only major Salinas River tributary which has remained un-dammed and as of 2015, still supported a small remnant population of the threatened Central Coast Steelhead trout (Oncorhynchus mykiss) that once spawned throughout in the Salinas River watershed. At one time it was also an important middle link for salmon migrating from the Salinas River to Tassajara Creek and other tributaries.[27] Estrella River also remains un-dammed. A 2015 assessment of the survivability of the river's steelhead trout indicated that such a survival may be unlikely, due to the river's recent tendency to run dry for most of the year.[28]

Other tributaries of the Salinas River that supported steelhead trout once included Paso Robles Creek, Jack Creek, Atascadero Creek, Santa Margarita Creek and Trout Creek in the upper reaches of the River. It once took over ten days for the steelhead from the upper part of the watershed to migrate to the Pacific Ocean near the City of Marina on Monterey Bay. From there, the steelhead would migrate to the area west of the Aleutian Islands before returning to the spawning grounds in the tributaries of the Salinas River.[6] As noted, the trout life-cycle which requires an annual migration to the sea and then back, was broken during the dry-river conditions of the years 2013 - 2016, and the current fate of the river's steelhead trout remains uncertain at best.

Father Pedro Font described salmon in the Salinas River (Rio de Monterey) on the de Anza Expedition in March, 1776:

...there are obtained also many good salmon which enter the river to spawn. Since they are fond of fresh water they ascend the streams so far that I am assured that even at the mission of San Antonio some of the fish which ascend the Rio de Monterey have been caught. Of this fish we ate almost every day while we were here.[29]

If Father Font was describing salmon, and not steelhead, then his records suggest that that salmon once traversed the Salinas River mainstem and up its San Antonio River tributary to Mission San Antonio near what is now Jolon. This may support other historical observer records primarily in the form of oral histories taken and compiled by Harold A. Franklin that placed Chinook salmon in the mainstem as far south as Atascadero where Highway 41 crosses, as well as southern tributaries of the Salinas River, including the Las Tablas Creek tributary of the Nacimiento River, and Jack Creek, a tributary of Paso Robles Creek west of Templeton.[30]

In regards to the area's historical beaver population, after a period of depletion by 19th century fur trappers, California golden beaver (Castor canadensis subauratus) populations rebounded and expanded their range from the Salinas River mouth at least to its San Antonio River tributary below the reservoir.[31][32] Although more recent accounts suggested that beaver are no longer found along the northern reaches of the river,[33] a recent comprehensive survey found beaver throughout the entire Salinas River mainstem and virtually all of its major tributaries.[34]

Agricultural use

The use of the river for irrigation in the Salinas Valley makes it one of the most productive agricultural regions in California. It is especially known as one of the principal regions for lettuce and artichokes in the United States. The river is shallow above ground, periodically dry, with much of its flow underground. The underground flow results from numerous aquifers, which are recharged by water from the Salinas, especially from the Nacimiento and San Antonio lakes during the dry months. In the 18th and early 19th centuries, the river valley provided the route of El Camino Real, the principal overland route from southern to northern Alta California, used by Spanish explorers and missionaries and early Mexican settlers.

River Road

Commencing from Hill Town, California running south along the western banks of the Salinas River to Gonzales, California is River Road. This road also falls along the edge of the Santa Lucia Highlands AVA, giving rise to its designation as River Road Wine Trail.

See also

- Anne B. Fisher — "The Salinas, Upside Down River"

- List of rivers of California

References

- Erwin G. Gudde, William Bright (2004). California Place Names: The Origin and Etymology of Current Geographical Names. University of California Press. p. 246. ISBN 978-0-520-24217-3.

- Hoover, Mildred B.; et al. (1966). Historic Spots in California. 3rd edition. Stanford, California: Stanford University Press. p. 219.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Salinas River

- Bancroft, Hubert H. (1884–1890). History of California. 7 vols. San Francisco, California: A.L. Bancroft and Company. p. v1/p150.

- Measured in Google Earth using the path measure tool

- Donald J. Funk, Adriana Morales (2002–2003). Upper Salinas River and Tributaries Watershed Fisheries Report and Early Actions (PDF) (Report). Upper Salinas Tablas Resource Conservation District. Archived from the original (PDF) on 28 July 2011. Retrieved 15 December 2010.

- USGS Spreckels Station River Flow Rate records (Note: Some "incomplete USGS site data" also available from 1929 through 1940)

- Three Parallel Portola Expedition 1769 diary accounts of Sept. 26, 1769. Pacifica History Project. Downloaded November 20, 2016.

- Monterey County, Historical Flooding of the Salinas River Monterey County Archives/ Archive.org. Downloaded March 26, 2020.

- 139 year Salinas precipitation annual average Western Regional Climate Center. Salinas weather- Period of Record : 02/01/1878 to 06/09/2016. Downloaded November 20, 2016.

- US Weather Service annual precipitation records for Salinas As reported by Wunderground Weather. Downloaded November 20, 2016

- Market Allocation of Agricultural Water Resources in the Salinas River Valley By John P. Neagley et. all. 1990. Downloaded November 20, 2016.

- Monterey County Well Permit Application Review Monterey County Water Resources Agency. Downloaded January 1, 2017.

- Salinas Valley Water Wars Tap Into a Well of Anger Los Angeles Times. September 17, 1998. By Mary Curtius. Downloaded January 10, 2017.

- Idaho Department of Water Resources IDWR legal actions index. Downloaded January 10, 2017.

- Key Salinas River Stakeholder: Steelhead Trout The Californian, October 23, 2015. By Natalie Jacewicz, downloaded January 3, 2017

- The Impact of Tectonic Activity in the Development of Monterey Submarine Canyon Monterey Naval Postgraduate School. By Robert Allen Lloyd, Jr. 1982. Downloaded November 26, 2016.

- Martin, G. (1999-12-20). "Bay Today, Gone Tomorrow". SF Gate. Hearst Communications. Retrieved 2017-01-20.

- U.S. Census Bureau History: 1906 San Francisco Earthquake U.S. Census Bureau. April 2016. Downloaded March 17, 2017.

- Salinas Groundwater Sustainability Agency Plan Salinas Groundwater Sustainability Agency. March, 2016. Downloaded December 4, 2016

- Looking Back: Salinas River, 1964 flooding Monterey Herald Newspaper, 10/23/2016, downloaded 10/28/2016.

- Officials try to figure out how to prevent Salinas River flooding before El Niño hits montereycountyweekly.com, Anna Ceballos, 10/1/2015, downloaded 10/28/2016

- David L. Durham (1998). California's geographic names: a gazetteer of historic and modern names of the state. Quill Driver Books. p. 1676.

- Summit point of Pine Ridge Geohack. Downloaded 11-26-2016.

- USGS Topos 7.5 Minute, Los Machos Hills. CA

- Salinas River Source Point Geohack. Downloaded 11-26-2016.

- "Ventana Wild Rivers Campaign: Arroyo Seco River, Tassajara Creek & Church Creek". Ventana Wilderness Alliance's Wild Rivers Campaign. Retrieved 2010-12-15.

- Key Salinas River stakeholder: steelhead trout The Californian. By Natalie Jacewicz. October 23, 2015. Downloaded March 5, 2017.

- Pedro Font. Expanded Diary of Pedro Font. Retrieved 2011-01-30.

- Franklin, Harold (1999). Steelhead and Salmon Migrations in the Salinas River (Report). p. 67.

- Barry Parr (2007). Explore! Big Sur Country: A Guide to Exploring the Coastline, Byways, Mountains, Trails, and Lore. Globe Pequot Press. p. 174. ISBN 978-0-7627-3568-6.

- "Salinas River National Wildlife Refuge". U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Retrieved 2010-12-16.

- Traveling the 150-mile span of the Salinas River yields lessons on the Valley-versus-Peninsula water battle. Monterey County Now. By David Schmalz & Sara Rubin. August 7, 2014. Downloaded March 3, 2017.

- Stuart C. Suplick (July 2019). Beaver (Castor Canadensis) of the Salinas River: A Human Dimensions-Inclusive Overview for Assessing Landscape-Scale Beaver-Assisted Restoration Opportunities (Thesis). California Polytechnic State University, San Luis Obispo. Retrieved August 8, 2019.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Salinas River (California). |

- Upper Salinas-Las Tablas Resource Conservation District

- Reference Information for the Salinas River

- County Of Monterey – county homepage