Amanzimtoti

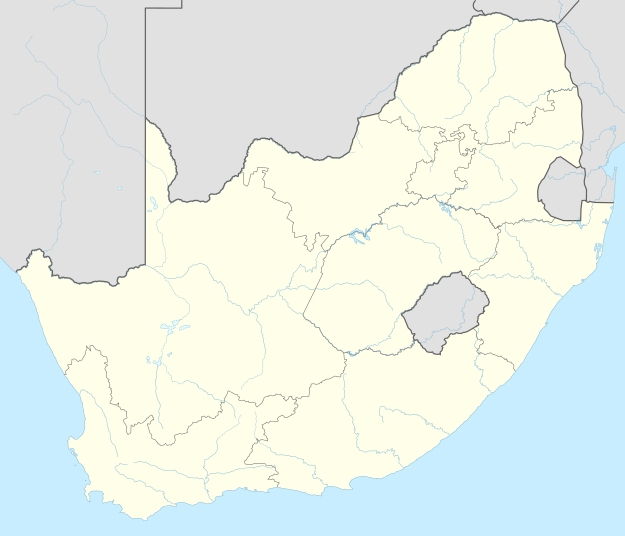

Amanzimtoti is a coastal town just south of Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. The town is well known for its warm climate and numerous beaches, and is a popular tourist destination, particularly with surfers, and the annual sardine run attracts many to the Tyron beaches.

Amanzimtoti Toti | |

|---|---|

Amanzimtoti Main Beach | |

Amanzimtoti  Amanzimtoti | |

| Coordinates: 30°03′S 30°53′E | |

| Country | South Africa |

| Province | KwaZulu-Natal |

| Municipality | eThekwini |

| Government | |

| • Type | Ward 97 |

| • Councillor | Andre Beetge (DA) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 9.19 km2 (3.55 sq mi) |

| Population (2011)[1] | |

| • Total | 13,813 |

| • Density | 1,500/km2 (3,900/sq mi) |

| Racial makeup (2011) | |

| • Black African | 22.1% |

| • Coloured | 1.9% |

| • Indian/Asian | 8.2% |

| • White | 67.3% |

| • Other | 0.5% |

| First languages (2011) | |

| • English | 50.9% |

| • Afrikaans | 30.6% |

| • Zulu | 14.0% |

| • Xhosa | 1.3% |

| • Other | 3.1% |

| Time zone | UTC+2 (SAST) |

| Postal code (street) | 4126 |

| PO box | 4125 |

| Area code | 031 |

Etymology

According to local legend,[2] when the Zulu king Shaka led his army down the south coast on a raid against the Pondos in 1828, he rested on the banks of a river. When drinking the water, he exclaimed "Kanti amanzi mtoti" (isiZulu: "So, the water is sweet"). The river came to be known as Amanzimtoti ("Sweet Waters"). The Zulu word for "sweet" is actually mnandi, but, as Shaka's mother had the name Nandi, he invented the word toti to replace mnandi out of respect not to wear out her name. Locals frequently refer to the town as "Toti".[3] In 2009 the KwaZulu-Natal Provincial Geographical Names Committee recommended changing the town's name to aManzamtoti/eManzamtoti.[4]

History

Precolonial period

King Shaka visited the area whilst on a raid down to Pondoland towards the end of his reign (1816 to 1828).[5] When Shaka stopped to rest in the area, he had his personal attendant collect water from a nearby stream.[5] This water was presented to King Shaka in a calabash.[5] After drinking the water he exclaimed "Kanti amanz'amtoti"[5] Extensions of the legend tell that King Shaka had sat under a large wild fig tree to drink the water, or that he used to meet local indunas (chiefs) under a specific fig tree.[5] The exact tree is unknown; one tree laying claim to the distinction fell down in March 1972, and another fell down in June 1981.[5]

Early colonial history

Dick King passed through the Amanzimtoti area on his way to Grahamstown in 1842 in order to request help for the besieged British garrison at Port Natal (now the Old Fort, Durban). The route that Dick King took through Amanzimtoti later became a road named Kingsway.

In 1847 Dr Newton Adams moved from Umlazi (where he had established a mission station in 1836) to Amanzimtoti and started a new mission station.[6] Dr Adams died in 1851, and the American Board of Commissioners for Foreign Missions sent Rev. Rood to Amanzimtoti in 1853 with the express object of opening up a school.[6] Adams Mission Church was built inland of Amanzimtoti in 1852, and Adams College was built in 1853.[3] The college was first named "Amanzimtoti Institute" and was later renamed after Dr. Adams in the 1930s.[6]

Different accounts identify the first house in the Amanzimtoti area, with one reference claiming a house on the south side of the Amanzimtoti River as the oldest house and another claiming a house to the north of the river as the oldest.[3][3] The "first house" in Amanzimtoti, known as Klein Frystaat ("Little Free State"), was owned by Howard Wright and was situated "on the north side of the back of the old Anglican Church" on Adams Road.[3] The house was demolished in 1984.[3] However, the "best guess" for the first house built in Amanzimtoti is 1895, and it may have been on the "headland" south of Amanzimtoti Lagoon.[5]

A photograph of a rowing-boat on the Amanzimtoti River taken in 1889 shows the banks of the river vegetated with Phragmites australis, Phoenix reclinata and coastal bush.[5] However a later traveler in 1911 claims to have been the first person to take a camera up the river, but also describes "reed-covered isles", "overhanging trees" and his photographs show Phoenix reclinata growing on the banks.[7]

The railway line from Durban to Isipingo was extended to Park Rynie from 1896 onwards, and the first train passed through Amanzimtoti in 1897.[3] This train left Durban on 22 February at 07h55 and consisted of a Dubs-type engine with two goods trucks, two passenger trucks and a brake-van.[5] There was a tin shanty siding at Amanzimtoti in 1897 which served as a station.[5] The route from the Amanzimtoti train station to Adams Mission was named Adams Road. The first hotel in Amanzimtoti was built in 1898 to cater for holidaymakers, some of whom came from as far afield as Johannesburg on specially organised trains.[3] The first hotel was built of wood and iron, but burnt down in May 1899.[5] Amanzimtoti had its first stationmaster in 1902.[5]

1900s

In 1902 Mrs K. Swafton visited Amanzimtoti and reported that the area had 1 hotel, 3 or 4 houses and 12 huts on the lagoon (clustered on the shore between the lagoon and Chain Rocks[5]). The huts were made of wood and iron or motor-car packing cases and served as holiday bungalows, and two of the houses had been built by the Department of Native Affairs for resident officers. The 5th house in Amanzimtoti was built on the corner of Adams Road and Ross Street in 1908 by the Reinbach family, who came from Cape Town.[3]

The Kynoch factory for the manufacture of explosives was built in Arklow, Ireland in 1895.[8] Mr Arthur Chaimberlain of Kynochs visited South Africa in 1907 to find a place to start another factory.[8] 1,400 acres of land were bought at Umbogintwini, and on 24 October 1907, a group of Irishmen (23 workers and their families) from Arklow sailed from Southampton to work as factory hands at the new Kynoch's factory in Umbogintwini.[8] These people lived in Amanzimtoti and Isipingo before the village of Umbogintwini took shape. One of these "Irishmen" (Harry Purves) was in fact originally from Durban, where he was born to Scottish immigrants.[9]

In 1910 Toti had "a dozen families" (according to Bill Bailey), and the Toti Hotel had 50 rooms. In 1911 Toti was an hour's ride from Durban by train, and a photograph shows a boat race held on the lagoon.[5] The Amanzimtoti River was navigable for 3.5 miles by rowing boat.[7]

In the 1920s a steam train (the Port Shepstone Express) passed through the town once a day, to and from Durban. At around this time there was a Zulu kraal where the original Amanzimtoti Primary School was later built. One of the bathing areas in the sea for holiday-makers was a gully with rocks sheltering it on either side. Mrs Miller (née Reinbach) and her husband Douglas Miller built a bungalow near this site in the early 1920s, and a tea room existed there in 1923. The two Reinbach brothers and a Mr Grainger were often called upon to rescue bathers, and it was decided to use the gully, and place suspended chains across it, to provide a safe area for bathers. The chains were put up sometime before 1926, and this place was then called Chain Rocks. Paul Henwood May moved to Amanzimtoti in 1922, and built several colonial-style homes (made from wood, with an iron roof and a front verandah).[3]

Many people moved to Amanzimtoti during the Great Depression, attracted by a cost-of-living cheaper than that in the cities.[3] Amanzimtoti was granted local administration in 1934, with a population of 774. One of the "highlights" of the 1930s was the arrival of Gracie Fields, a popular singer at the time. Electricity was introduced to the town in 1938; being voted in by a small majority after Alan Allen campaigned on the benefits of electricity. Telephone lines were installed in 1945, and the manually-operated telephone-exchange was located at the railway station. Running water was introduced in 1949 by the first mayor of Amanzimtoti, Mr Olaf Bjorseth. Before the introduction of running water, residents used to collect rain water from the roofs of their houses. The first petrol pump in the town was owned and operated by Mr and Mrs Silverstone, who also ran a store called "The Silverstones". The first post office was situated on the railway station, next door to Mrs Morton's Tea Room. Mrs North was the first post-mistress. The post office and telephone exchange moved to the Telephone Exchange building in Bjorseth Crescent in the late 1940s / early 1950s.[3]

Amanzimtoti offered refuge to many Middle Eastern and British evacuees during the Second World War, many of whom lived in holiday cottages and in private homees. When first a school was started at Toti Town Hall, Dr Frickle paid for two teachers' salaries out of money he made at his clinic selling "No 9s" (red pills "from the army"), which he purportedly prescribed "for everything". Miss Burns (who ran the Guides) held the first Arbour Day in Natal, and along with 16 Guides, planted 60 Erythrina lysistemon trees along Beach Road.[3] These trees "blazed red" when in flower and were known as the "glory of Beach Road" - and for this reason, the Coral Tree is included in the crest of Amanzimtoti. These trees were however cut down in the 1950s when Beach Road was widened and tarred.[3]

The first newspapers to be produced in the town were attributed to Ivor Language, and the first issue of The Observer was printed in July 1955.[3] Before this, newspapers had been brought in by train from Durban. From 1957 to 1959, The Observer was replaced by a commercial weekly newspaper, the South Coast Courier. The Observer was again replaced, this time by the South Coast SUN, which Archie and Jenny Taylor started in 1970.

Toti's largest building, then known as Sanlam Centre, was constructed during 1972/1973. It consisted of a shopping complex and a 25-storey block of flats, which can accommodate 1,500 people.[3]

Recent history

Amanzimtoti made the international news when on 23 December 1985, during the peak of the Christmas shopping season, Umkhonto we Sizwe cadre Andrew Sibusiso Zondo detonated a bomb in a rubbish bin at the Sanlam shopping centre in an act of terrorism. Five people (two women and three children[10]) were killed in the blast and more than forty suffered injuries.[11]

Wildlife

Amanzimtoti is home to a wide variety of wildlife, including Cape clawless otters, blue duiker and spotted ground-thrush. Vervet monkeys are common and can be seen throughout the suburban parts of the town and in the nature reserves.

Most of the wildlife can be found along the Amanzimtoti River or in the coastal dune vegetation. A nature reserve was established along the banks of the river in 1965 called Ilanda Wilds. There is also a 'bird park' called Umdoni Bird Sanctuary along one of the tributaries of the Amanzimtoti River. Other nature reserves and green areas include; Umbogavango, Vumbuka, and the Pipeline Coastal Park.

Coat of arms

Amanzimtoti was a borough in its own right from 1952 to 1996. It obtained a coat of arms from the College of Arms in November 1958, and registered it with the Natal Provincial Administration in April 1959.[12]

The arms were : Barry wavy Argent and Azure, on a mount a coral tree proper within an orle of eleven coral flowers also proper (i.e. a coral tree surrounded by eleven coral flowers on a background of silver and blue wavy stripes).

The crest was an egret standing in a circle of coral flowers, and the motto Nitamur semper ad optima.

References

- "Main Place Amanzimtoti". Census 2011.

- http://amanzimtoti.kzn.org.za/index.php?cityhome+662+++57619

- Howard, G. (April 2000). South Coast Sun: Times of Toti.

- IOL News: Get ready to rewrite the map of KwaZulu-Natal: http://www.iol.co.za/index.php?click_id=13&art_id=vn20031007033359722C450824&set_id=1, retrieved 25 August 2011.

- Meitener, M.J. (1994). A History of Amanzimtoti. The Rapid Results College.

- Adams College - Historical Background: http://www.adamscollegesa.co.za/site/adams-college Archived 18 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine, retrieved 26 August 2011.

- Tatlow, A.H. (1911). Natal Province: Descriptive Guide and Official Hand-book. South African Railways Printing Works, Durban, Natal.

- Donald Inggs. Twini's historic Irish Connection.

- Margaret Isabella Nicol. The Breakfast Room Table.

- IOL News: Honouring a killer?: http://www.iol.co.za/news/south-africa/honouring-a-killer-1.349597, retrieved 25 08 2011.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 17 June 2008. Retrieved 16 December 2008.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Natal Official Gazette 2914 (30 April 1959).

External links

- www.amanzimtoti.org provides information relevant to the local and internet community as well as for travelers visiting Amanzimtoti

- Amanzimtoti.net, another community website

- Amanzimtoti Tourism

- totiblog.co.za

- Galleria website

- Amanzimtoti property for sale

- Surf video

- Social tweets

.svg.png)