Demopolis, Alabama

Demopolis is the largest city in Marengo County, Alabama, in southwest Alabama. The population was 7,483 at the time of the 2010 United States Census.[3]

Demopolis, Alabama | |

|---|---|

Aerial view of Demopolis, Alabama. The confluence of the Tombigbee and Black Warrior Rivers is visible in the center of the picture. View is to the northwest. | |

| Nickname(s): City of the People, Jewel of the Black Belt, The River City, The Canebrake, Demop | |

Location of Demopolis in Marengo County, Alabama. | |

| Coordinates: 32°30′34″N 87°50′14″W | |

| Country | United States |

| State | Alabama |

| County | Marengo |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | John Laney |

| Area | |

| • Total | 18.06 sq mi (46.78 km2) |

| • Land | 17.74 sq mi (45.94 km2) |

| • Water | 0.32 sq mi (0.84 km2) |

| Elevation | 121 ft (37 m) |

| Population (2010) | |

| • Total | 7,483 |

| • Estimate (2019)[2] | 6,612 |

| • Density | 372.76/sq mi (143.92/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 (Central (CST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-5 (CDT) |

| ZIP code | 36732 |

| Area code(s) | 334 |

| FIPS code | 01-20296 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0117222 |

| Website | demopolisal.gov |

The city lies at the confluence of the Black Warrior and Tombigbee rivers. It is situated atop a cliff composed of the Demopolis Chalk Formation, known locally as White Bluff, on the east bank of the Tombigbee River.[4][5] It is at the center of Alabama's Canebrake region and is also within the Black Belt.[6][7][8]

Demopolis was founded after the fall of Napoleon's Empire and named by a group of French expatriates, a mix of exiled Bonapartists and other French migrants who had settled in the United States after the overthrow of the colonial government in Saint-Domingue following the failed Saint-Domingue expedition. The name, meaning in Greek "the People's City" or "City of the People" (from Ancient Greek δῆμος + πόλις), was chosen to honor the democratic ideals behind the endeavor. First settled in 1817, it is one of the oldest continuous settlements in Alabama.[9][10] It was incorporated on December 11, 1821.[11]"

History

Colonization

Organizing themselves first in Philadelphia, French expatriates petitioned the U.S. Congress to sell them property for land to colonize. Congress granted approval by an act on March 3, 1817 that allowed them to buy four townships in the Alabama Territory at $2 per acre, with the provision that they cultivate grape vines and olive trees. Following advice obtained from experienced Western pioneers, they determined that Alabama would provide a good climate for cultivating these crops. By July 14, 1817, a small party of pioneers had settled at White Bluff on the Tombigbee River, at the present site of Demopolis, founding the Vine and Olive Colony.[12]

Most prominent and wealthiest among the immigrants was Count Lefebvre Desnouettes, who had been a cavalry officer with the rank of Lieutenant-General, under Napoleon. Considered Napoleon's best friend, he had ridden in Napoleon's carriage during his failed invasion of Russia. Other prominent figures among them included Lieutenant-General Baron Henri-Dominique Lallemand, Count Bertrand Clausel, Joseph Lakanal, Simon Chaudron, Pasqual Luciani, Colonel Jean-Jerome Cluis, Jean-Marie Chapron, Colonel Nicholas Raoul, and Frederic Ravesies. Most of these expatriates had little interest in pioneer life and sold their shares in the colony, remaining in Philadelphia.[13] By 1818, the colony consisted of only 69 settlers.[14]

Due to a variety of adversities, their pioneering efforts were not the great success for which they had hoped. Following a survey in August 1818, they were to find that their new homes did not fall under the territories encompassed by the congressional approval, and the Vine and Olive Colony was soon forced to move. They learned that their actual land grants began less than a mile to the east of their newly cleared land. After abandoning the settlement of Demopolis, they soon established two other towns, Aigleville and Arcola.[15]

American settlement

Upon learning of the survey and that the French grants lay elsewhere, American settlers began to quickly purchase the property of the former French settlement with the intent of turning it into a major river port. A land company was formed in 1819 with the express purpose of purchasing the land and laying off of a town, the White Bluff Association (later renamed the Company of the Town of Demopolis). George Strother Gaines was named as the company spokesman and he bought the town site atop White Bluff as soon as it offered for sale. Commissioners for the company were George Strother Gaines, James Childress, Walter Crenshaw, Count Charles Lefebvre Desnouettes, and Dr. Joseph B. Earle.[10]

The commissioners were responsible for overseeing the survey of the site, lot sales, and the early operations of the town. The commissioners laid off the site into streets, blocks, and lots, with a block of roughly two acres divided into eight lots. The Demopolis Town Square, encompassing one city block, was established in 1819. The first lots were sold beginning on April 22, 1819. When Count Desnouettes died in 1822, Allen Glover was appointed to replace him. As other commissioners retired they were succeeded by David E. Moore, William H. Lyon, Thomas McGee, and George N. Stewart.[10]

The streets were laid off utilizing a grid plan, using Philadelphia as a model. The original streets running north-south were named for trees, such as Ash, Cedar, Cherry, and Chestnut. Exceptions were made for Commissioners, Strawberry, and Market (now Main) streets. Several short north-south streets were also named for commissioners, such as Desnouettes, Earle, Glover, Griffin, and McGee. The east-west streets were named for national and local heroes, as well as commissioners, such as Childress, Fulton, Gaines, Lyon, Monroe, Washington, Franklin, Jefferson, and Jackson. Most streets were designed to be 66 feet (20 m) wide. A strip of land that remained public property, for the use of all, was the land adjoining the Tombigbee River from where Riverside Cemetery is today, to the southwest of the city proper, all the way to the Upper Landing in the north, with Arch Street following the route along the top of the cliff. Only the portion of Arch Street adjacent to the cemetery remains intact.[10]

Some flaws and limitations of the original town plan had become apparent by the late 1820s and 1830s. The typical town lots, at 75 feet (23 m) wide and 150 feet (46 m) deep were not conducive to the building of the stately homes desired by the more prosperous citizens of the town, although some grand mansions did begin to appear by the late 1820s. One of the first was the brick 2 1⁄2-story Federal-style Allen Glover house at the foot of Capitol street. It was one of the, if not the first neoclassical structure to appear in Marengo County. It was soon followed by Bluff Hall, built in 1832 by Allen Glover for his daughter, Sarah Serena, and son-in-law, Francis Strother Lyon.[10]

One major flaw in the town plan was that there was no clearly defined business district, resulting in commercial and residential buildings mixed together all over town. This eventually resulted in numerous blighted areas. Some stores did open around the town square, however, and warehouses started to appear adjacent to the town's three major river landings, Upper Landing, above the modern Demopolis Yacht Basin and Marina, Webb's Landing at the western terminus of Washington Street, and Lower Landing to the west of Riverside Cemetery and the Whitfield Canal.[10][16][17][18]

By the 1830s Demopolis had developed into a regional commercial river hub, attracting American and European-born craftsmen and merchants including the Beysiegle, Breitling, Breton, Dupertuis, Foster, Hummell, Kirker, Knapp, Marx, Michael, Mulligan, Oberling, Rhodes, Rudisill, Rosenbaum, Schmidt, Shahan, Stallings, and Zaiser families. Numerous plantation owners also established townhouses in the community or on its outskirts, including the Allen, Ashe, Curtis, DuBose, Foscue, Glover, Griffin, Lane, Lyon, McAllister, Prout, Reese, Strudwick, Tayloe, Whitfield, and Vaughan families. However, unlike many other towns in the Canebrake and Black Belt, Demopolis was never overwhelmed by a homogeneous planter class that came to dominate so many of the others. During these years and those to come, the rivers brought in a large itinerant population with a desire for raucous entertainment. This created a profitable and brisk trade for those operating taverns and did much to earn early Demopolis a reputation for decadence.[10]

During the 1840s many of the streets laid out by the town fathers had yet to be opened to traffic. The town council focused much of its attention on clearing the intended streets of obstacles and opening them to traffic, other street improvements, and the building of wooden sidewalks along major thoroughfares. The council also approved measures for protecting trees in the common areas and streets. Several town ordinances were enacted in 1842 to further restrain the enslaved African American population. These included the prohibition of selling or purchasing any article or commodity from or to a slave without written permission from their master or overseer, no slave was allowed to purchase alcohol without written consent, if any slave were convicted of assault upon "any white man, negro, or mulatto" the owner would be fined $50, any slave caught running "any horse, gelding, or mule" through town would be subject to fifteen lashes unless the owner pays a fine of $1, any slave caught driving any wagon or cart or driving a horse or mule on or across the sidewalks of the town would be subject to 10 lashes unless the owner pays a fine of 50 cents.[10]

With its eclectic mix of citizenry, Demopolis was slow to erect houses of worship. In fact, a group of Methodist ministers convened nearby in 1843 pronounced Demopolis as "wholly irreligious." Mainline Protestant churches were slow to take root, in fact, no churches at all were built in Demopolis until 1840. Prior to that time, various denominational groups met in a log assembly house on the town square until it was torn down in 1844. A Baptist group had been established in the 1820s but ended due to a lack of support. The Episcopalians established a congregation in 1834, but did not build their Trinity Episcopal Church until 1850. A Presbyterian congregation was established in 1839 and completed their first church, a brick structure now known as Rooster Hall, on the town square in 1843. The Methodist congregation was established in 1840 and the first building was completed in 1843.[19]:6–8 Present in Demopolis from the beginning, the Catholic congregation in town was listed as a mission of Saint John the Baptist in Tuscaloosa in 1851. It was switched to Selma in 1880. They met in a small frame church and private homes until the current Saint Leo the Great was built in 1905. The Jewish congregation, B'nai Jeshurun, was established in 1858, although the community had been present since the 1840s. B'nai Jeshurun was the fourth Jewish congregation established in Alabama.[20] They initially met in homes and businesses until eventually building a Moorish Revival-style temple in 1893.[19]:6–8[21]

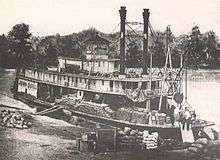

By the 1850s several palatial steamboats were visiting the town as a regular stop on the Mobile to Columbus, Mississippi route along the Tombigbee. These included the Forest Monarch, Alice Vivian, and the ill-fated Eliza Battle. Several others were dedicated to almost exclusively to Demopolis and the cotton trade, including the Allen Glover, Canebrake, Cherokee, Demopolis, Frank Lyon, Marengo, and the Mollie Glover. Major hotels during this same period included the Planter's Hotel, later known as Madison House Hotel, and the River Hotel.[22]

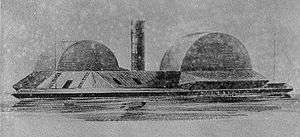

The year 1853 saw a yellow fever epidemic strike the city, with some interments in an ill-defined two-acre cemetery to the north of town in the river bend. The Jewish Cemetery was established in 1878 to the east of town on Jefferson Street. The Glover Mausoleum was completed on the banks of the Tombigbee in 1845, with the burial of many family members in and around it. This led to the establishment of the main burial ground for the city, Riverside Cemetery, officially opened with the sale of additional plots to the public in 1882.[10] A circular Gothic Revival-style amphitheater, complete with a crenelated roof-line, was completed in 1859 north of town in Webb's Bend at the fairgrounds. The fairgrounds and its buildings covered approximately 20 acres (8.1 ha) and hosted a variety of events until the outbreak of the Civil War.[23]

By 1860, the population within the town limits had grown to approximately 1,200 people.[19]:339 The wealthiest citizens were, in order from the highest real and property values, Gaius Whitfield, Goodman G. Griffin, Nathan B. Whitfield, Augustus Foscue, Francis S. Lyon, Gottlieb Breitling, George F. Glover, Simeon Wheeler, Daniel F. Prout, George G. Lyon, Henry W. Reese, Benjamin N. Glover, Cecile Fournier Poole, Evelina H. Henley, David Compton, Jr., Alexander M. McDowell, Augustus Zaiser, Alexander Fournier, Timothy G. Cornish, and Luther G. Houston.[24] The town began to attract new entertainments, such as musical and dramatic performances, concert artists, lecturers, circuses, and carnivals, but the reality of war soon ended all of that.[25]

Civil War and aftermath

Marengo County, with its large number of slaveholders, was decidedly in favor of the secession from the Union and the formation of the Confederate States of America. These feelings ran high in the county's largest town also. Prominent secessionists included Nathan B. Whitfield, Francis S. Lyon, Goodman G. Griffin, Kimbrough C. DuBose, George B. Lyon, Dr. James D. Browder, and George E. Markham. However, many other powerful men in town had opposed secession, including Benjamin Glover Shields, William H. Lyon, Jr., William B. Jones, Pearson J. Glover, Gaius Whitfield, Alfred Hatch, Joel C. DuBose, Robert V. Montague, and Henry Augustine Tayloe. In the end, however, most men on both sides of the argument joined in the Confederate cause once secession was inevitable.[26]

With the start of the Civil War, several Confederate companies drew heavily from the population of the Demopolis area and Marengo County. These included the 4th, 11th, 21st, 23rd, and 43rd Alabama Infantry Regiments in addition to the 8th Alabama Cavalry, Company E of the Jeff Davis Legion, and Selden's Battery. During the course of the war, more of these men would be lost to exhaustion, disease, and malnutrition than to battle. The city itself, on two navigable rivers and a railroad, became home to a number of Confederate installations and offices. These included commissary and quartermaster offices and warehouses, engineers' offices and workshops, a large ordnance depot, two large hospitals, offices of the medical purveyor of the Department of Alabama, Mississippi, and East Louisiana, and a huge military encampment at the fairgrounds in Webb's Bend. These brought in thousands of soldiers into town at a time, one that had just over a thousand of its own inhabitants prior to the war, putting an enormous strain on food and accommodations in the town. Many hundreds of the soldiers who died in the hospitals during the war were buried in a Confederate cemetery on the south end of Webb's Bend, but the site is underwater today, following the damming of the river below Demopolis in the 20th century.[26]

After the loss of its primary east-west railroad during the war, the Confederate government completed the Alabama and Mississippi Rivers Railroad from Selma through Demopolis and on to Meridian, Mississippi in 1862. The project had been in the works since the 1850s, but several miles between Demopolis and Uniontown had not been finished when war erupted. As the war raged in all directions around Demopolis in 1864, the city was subjected to a huge influx of war refugees. Nathan B. Whitfield noted in his journal that those from Mobile had taken every available vacant house and the others were crowded with natives along with their descendants and relatives.[26]

March 1865 saw Demopolis preparing to defend the town against Union threats, with the fortification of key positions. Three circular batteries, surrounded by earthworks, were constructed and other fortifications built across the southern reaches of town. With the impending fall of Selma in early April, during Wilson's Raid, all of the railroad's rolling stock was sent full of supplies westward through Demopolis and on to Meridian. A flotilla of eighteen Confederate gunboats and packet ships were relocated to the Tombigbee River at Demopolis around this same time. These included the CSS Nashville, CSS Morgan, CSS Baltic, the Southern Republic, Black Diamond, Admiral, Clipper, Farrand, Marengo and St. Nicholas.[26]

With the surrender of the last of the Confederates, Demopolis found itself a much different city from what it had been prior to the war. At the end of May 1865, the townspeople learned that an occupying force of Federal soldiers, the 5th Minnesota Infantry, were en route to occupy the town. Once there, they occupied the former fairgrounds. Despite the usual unpleasantness associated with the occupation of many defeated Southern towns, two of the Minnesota commanders, Colonel William B. Gere and General Lucius Frederick Hubbard apparently came to be well-liked by the townspeople. Despite some bright spots in relations, the Episcopal Church in the South was slow to give up on the notion of the Confederacy, resulting in the military governor of Alabama closing all Episcopal churches in the state, effective on September 20, 1865. Trinity Episcopal Church in Demopolis was put under Federal guard, and during this time the church mysteriously burned down. Blame was placed on the soldiers for intentionally burning it, but this has never been born out by the facts. Aside from all of this, the more pressing matter was the devastated economy of the community and surrounding countryside, a problem that would continue through the Reconstruction era.[27]

During Reconstruction, the new authorities in charge of the government decided to move the county seat of Marengo from its central location in Linden to Demopolis by an act approved on December 4, 1868. The county appointed Richard Jones, Jr., Lewis B. McCarty, and Dr. Bryan W. Whitfield to build or buy a new courthouse in Demopolis. They negotiated the purchase of the Presbyterian church on the town square, now known as Rooster Hall, for the sum of $3000. It was conveyed to the county on April 8, 1869. The county built a fireproof brick building next door to the former church in 1869–70 to house the probate and circuit clerk offices. This building serves as Demopolis City Hall today. The move of the county seat was highly controversial, and the Alabama Legislature set April 18, 1870 as the date for a county-wide referendum to decide if Dayton, Demopolis, or Linden would become the county seat. Due to the closeness of the vote and voting irregularities, a run-off between Linden and Demopolis was set for May 14, 1870. Irregularities appeared again and votes from Dayton, mostly in favor of Linden, were rejected by the board of supervisors. Linden continued an attempt to persuade the state legislature to move the county seat back to their town, with success in February 1871. The former courthouse buildings reverted from county ownership to Demopolis and remain city property today.[28]

20th century

The struggle to rebuild the economy of Demopolis and the surrounding region continued into the 20th century. The growing, trading, and milling of cotton continued to be a major basis of the economy up until the World War I-era. The boll weevil infestations of the 1920s and the Great Depression of the 1930s finally ended the one-crop farming system.[29]

Demopolis had electric lights, water works and a sewerage system, chert-covered streets, paved sidewalks, and a fire department by the second decade of the 20th century. It was increasingly serving as a major banking and retail hub in the region during this time. Major financial institutions included the Commercial National Bank, City Bank and Trust Company, and Robertson Banking Company. One of the first large department stores of note in the area, Mayer Brothers, built its three-story brick building adjacent across from the public square in 1897 and operated for most of the 20th century. That building is now utilized by Robertson Banking Company. The Rosenbush Furniture Company was established in 1895 and operated until 2002.[30] The J. H. Spight Grocery was established in 1901 as one of the earliest and most successful grocery stores for more than 50 years, prior to the era of corporate chain stores. Although the community had many newspapers throughout its first 100 years, the only one to survive into the 21st century, The Demopolis Times, was established in 1904.[29][31]

A number of theaters sprang up in the city, beginning in the late 19th century. Rooster Hall, following its incarnations as a church, courthouse, and then a city property, was leased for use as the Demopolis Opera House from 1876 to 1902. It hosted live dramatic performances, civic lectures, and minstrel shows. The Braswell Opera House, with its ornate interior and private box galleries, opened on October 23, 1902, with a performance of Louisiana playwright Epsy William's Unorna. It continued as an entertainment venue into the 1920s and was eventually demolished in 1972–73. The first theater built for the presentation of motion pictures, the Elks Theater, opened on October 1, 1915. It was renamed the Si-Non in 1916. The building was restored during the 1990s.[32]

Following the demise of cotton production, beef cattle farming and, more recently, catfish aquaculture became new major agricultural pursuits. Industrial activities became the major sources of employment by mid-century, with the cement, lumber, and paper industries playing a prominent role in the city's economy into the 21st century.[29]

Geography

Demopolis is located at 32°30'34" North, 87°50'14" West (32.509465, −87.837265).[33] According to the U.S. Census Bureau, the city has a total area of 12.5 square miles (32 km2), of which 12.2 square miles (32 km2) is land and 0.2 square miles (0.52 km2) (2.00%) is water.

Transportation

Major roads include two U.S. highways: U.S. Route 80 runs east–west through the city and U.S. Route 43 runs north–south. Alabama state highways include State Route 8, State Route 13, and nearby State Route 69 and State Route 28. A proposed Interstate 85 extension from Interstate 59/20 near the Mississippi state line to Interstate 65 near Montgomery is planned to pass near the city.[34] A bus system is operated by West Alabama Transportation.

Demopolis is served by several railway companies, including Norfolk Southern Railway, BNSF Railway, and the Alabama and Gulf Coast Railway.

The Alabama State Port Authority has inland docks at the Port of Demopolis with direct access to inland and Intracoastal waterways serving the Great Lakes, the Ohio and Tennessee rivers and the Gulf of Mexico via the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway.[35]

The Demopolis Municipal Airport is located northwest of the city, adjacent to Airport Industrial Park and the Tennessee-Tombigbee Waterway. It has a 5,000-foot runway and a ten-unit hangar.[36]

Intercity bus service is provided by Greyhound Lines.[37]

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1850 | 812 | — | |

| 1860 | 473 | −41.7% | |

| 1870 | 1,539 | 225.4% | |

| 1880 | 1,389 | −9.7% | |

| 1890 | 1,398 | 0.6% | |

| 1900 | 2,606 | 86.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,417 | −7.3% | |

| 1920 | 2,779 | 15.0% | |

| 1930 | 4,037 | 45.3% | |

| 1940 | 4,137 | 2.5% | |

| 1950 | 5,004 | 21.0% | |

| 1960 | 7,377 | 47.4% | |

| 1970 | 7,651 | 3.7% | |

| 1980 | 7,678 | 0.4% | |

| 1990 | 7,512 | −2.2% | |

| 2000 | 7,540 | 0.4% | |

| 2010 | 7,483 | −0.8% | |

| Est. 2019 | 6,612 | [2] | −11.6% |

| sources:[3][19]:6–8[38][39][40][41][42][43][44] 2013 Estimate[45] | |||

During the 2000 United States Census, there were 7,540 people, 3,014 households, and 2,070 families residing in the city. The population density was 616.4 people per square mile (238.0/km2). There were 3,311 housing units at an average density of 270.7 per square mile (104.5/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 50.90% Black or African American, 47.75% White, 0.09% Native American, 0.20% Asian, none Pacific Islander, 0.48% from other races, and 0.58% from two or more races. 0.98% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.[39]

There were 3,014 households, out of which 34.9% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 43.1% were married couples living together, 22.5% had a female householder with no husband present, and 31.3% were non-families. 28.9% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.3% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.48 and the average family size was 3.05.[39]

In the city, the population was spread out, with 29.1% under the age of 18, 8.4% from 18 to 24, 26.6% from 25 to 44, 21.6% from 45 to 64, and 14.3% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 36 years. For every 100 females, there were 81.5 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 75.0 males.[39]

The median income for a household in the city was $26,481, and the median income for a family was $35,752. Males had a median income of $37,206 versus $20,265 for females. The per capita income for the city was $16,687. About 26.0% of families and 30.6% of the population were below the poverty line, including 38.3% of those under age 18 and 21.1% of those age 65 or over.[39]

2010 census

During the 2010 United States Census, there were 7,483 people, 3,049 households, and 1,998 families residing in the city. The population density was 613.4 people per square mile (236.1/km2). There were 3,417 housing units at an average density of 280.1 per square mile (107.8/km2). The racial makeup of the city was 50.1% Black or African American, 47.3% White, 0.1% Native American, 0.5% Asian, none Pacific Islander, 1.1% from other races, and 0.8% from two or more races. 2.4% of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race.

There were 3,049 households, out of which 31.2% had children under the age of 18 living with them, 38.6% were married couples living together, 23.3% had a female householder with no husband present, and 34.5% were non-families. 31.2% of all households were made up of individuals, and 12.0% had someone living alone who was 65 years of age or older. The average household size was 2.42 and the average family size was 3.04.

In the city, the population was spread out, with 27.0% under the age of 18, 8.8% from 18 to 24, 24.1% from 25 to 44, 25.3% from 45 to 64, and 14.8% who were 65 years of age or older. The median age was 37.1 years. For every 100 females, there were 80.7 males. For every 100 females age 18 and over, there were 78.2 males.

The median income for a household in the city was $35,583, and the median income for a family was $49,973. Males had a median income of $50,734 versus $31,520 for females. The per capita income for the city was $21,116. About 19.1% of families and 26.8% of the population were below the poverty line, including 25.4% of those under age 18 and 27.5% of those age 65 or over.

Government

| District | Representative | Position |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Charles Jones, Jr | Councilman |

| 2 | Nathan Hardy | Councilman |

| 3 | Harris Nelson | Councilman |

| 4 | Bill Meador | Councilman |

| 5 | Cleveland Cole | Councilman |

| ALL | John Laney | Mayor |

Demopolis is governed by a mayor–council system. The mayor is elected at large to a four-year term and functions as the executive officer, appointing department heads and advisory board members and signing off on all motions, resolutions and ordinances passed by the council.[47]

The city council consists of five members who are elected from single member districts. The council controls all legislative and policy-making for the city through the use of ordinance, resolution or motion. The council also adopts the annual budget and confirms appointments made by the mayor.[47]

Education

The city runs its own citywide public school system, the Demopolis City School District. Private schools in the city included one integrated Christian school, West Alabama Christian School, which closed in 2018. The city is also home to the Demopolis Higher Education Center. The facility, which opened in 2004, is a 15,000 square feet structure, including a library and open area student atrium, a science lab, conference room, six multimedia classrooms, and two computer labs; Community Rooms provide one of the largest and most modern meeting spaces in Marengo County. The University of West Alabama is the managing partner of the center.

Historic sites

Gaineswood is an antebellum historic house museum on the National Register of Historic Places and is a listed National Historic Landmark. It was built between 1843–61 in an asymmetrical Greek Revival style. It features domed ceilings, ornate plasterwork, columned rooms, and most of its original furnishings. Gaineswood is owned and operated by the Alabama Historical Commission.[48]

Bluff Hall is an antebellum historic house museum on the National Register of Historic Places. It was built in 1832 in the Federal style and modified in the 1840s to reflect the Greek Revival style. It is owned and operated by the Marengo County Historical Society.[49]

Laird Cottage is a restored 1870 residence with a mix of the Greek Revival and Italianate styles. It currently serves as the headquarters of the Marengo County Historical Society and also houses history exhibits and the works of Geneva Mercer, a Marengo County native who gained fame as an artist and sculptor. She served as an intern to Giuseppe Moretti, the sculptor who created Birmingham's monumental Vulcan. Following her internship, she lived and worked with Moretti and his wife until his death.[50]

Other historic sites in Demopolis include White Bluff, the Demopolis Historic Business District, Demopolis Town Square, Lyon Hall, Ashe Cottage, the Curtis House, the Glover Mausoleum, and the Foscue-Whitfield House.[51]

Demopolis in the arts

The Marx and Newhouse families of Demopolis were reputedly the inspiration for The Little Foxes, a Broadway play. The melodrama was written by Lillian Hellman, whose maternal ancestors were all natives of Demopolis. It was first performed in 1939, with Alabama-born actress Tallulah Bankhead giving a legendary performance in the lead role of Regina. This hit production ran a year on Broadway. The 1941 film version was directed by William Wyler and starred Bette Davis, Herbert Marshall and Teresa Wright. It was nominated for an Academy Award for Best Picture in 1941. In 1949 the play was adapted into an opera by Marc Blitzstein, under the title Regina.[52][53][54]

Lillian Hellman's 1946 play, Another Part of the Forest, was also loosely based on her Demopolis ancestors.[53]

The 1949 film, The Fighting Kentuckian, is set in Demopolis and tells a story about an interaction with the original French settlers. The basic plots features two Kentuckians returning from service with Andrew Jackson's forces in the War of 1812. Their unit passes through the port of Mobile, Alabama, where John Breen, played by John Wayne, meets the pretty Fleurette De Marchand, played by Vera Ralston, from Demopolis. He makes sure the unit passes through Demopolis on its way back home and he stays there as the unit leaves. He discovers that De Marchand is about to marry a wealthy riverman and a love triangle ensues, with Breen eventually winning out.[55]

The 2015 play Alabama Story has a subplot featuring the characters Joshua Moore and Lily Whitfield, who grew up in Demopolis as childhood friends on Lily's father's cotton plantation, now estranged.[56]

See also

Climate

The climate in this area is characterized by hot, humid summers and generally mild to cool winters. According to the Köppen Climate Classification system, Demopolis has a humid subtropical climate, abbreviated "Cfa" on climate maps.[57]

References

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 29, 2020.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved 2008-01-31.

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. April 15, 2008.

- "ADAH: Marengo Historical Markers". "Alabama Department of Archives and History". Archived from the original on August 21, 2007. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- John C. Hall (August 17, 2007). "Canebrakes". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "Alabama's Canebrake". West Alabama Regional Alliance. Archived from the original on June 23, 2011. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- Terance L. Winemiller (September 17, 2009). "Black Belt Region in Alabama". The Encyclopedia of Alabama. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- Blaufarb, Rafe. Bonapartists in the Borderlands: French Exiles and Refugees on the Gulf Coast, 1815–1835. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press, 2006.

- Smith, Winston (2003). The Peoples City: The Glory and the Grief of an Alabama Town 1850–1874. Demopolis, Alabama: The Marengo County Historical Society. pp. 32–56. OCLC 54453654.

- Owen, Thomas McAdory; Marie Bankhead Owen (1921). History of Alabama and dictionary of Alabama biography, Volume 1. S. J. Clarke Publishing Company. p. 266.

- Smith, Winston. Days of Exile: The Story of the Vine and Olive Colony in Alabama, pages 31–43. Tuscaloosa, Alabama: W. B. Drake and Son, 1967.

- Smith, Days of Exile, 96–115.

- Blaufarb, Rafe (May 19, 2008). "Vine and Olive Colony". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- Smith, Days of Exile, 47–53.

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Demopolis Upper Landing

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Webb's Landing

- U.S. Geological Survey Geographic Names Information System: Demopolis Lower Landing (historical)

- Smith, The Peoples City

- "Alabama". Encyclopedia of Southern Jewish Communities. Goldring / Woldenberg Institute of Southern Jewish Life. Retrieved October 5, 2010.

- Marengo County Heritage Book Committee: The heritage of Marengo County, Alabama, pages 34–46. Clanton, Alabama: Heritage Publishing Consultants, 2000. ISBN 1-891647-58-X

- Smith, The Peoples City, 16–19

- Smith, The Peoples City, 73–74.

- Smith, The Peoples City, 339.

- Smith, The Peoples City, 105-56.

- Smith, The Peoples City, 129–218.

- Smith, The Peoples City, 219–332.

- Smith, The Peoples City, 268–274.

- "History of Demopolis". City of Demopolis. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- Andrew Muchin. "A Town's Last Jew Provides a Legacy of Generosity". Yesterdays of Demopolis. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- Owen, History of Alabama and dictionary, 482–483.

- "Historic Markers: Marengo County". The Alabama Historical Association. Alabama Department of Archives and History. Archived from the original on June 20, 2010. Retrieved June 1, 2011.

- "US Gazetteer files: 2010, 2000, and 1990". United States Census Bureau. February 12, 2011. Retrieved April 23, 2011.

- "I-85 Extension Corridor Study Environmental Impact Statement". Alabama Department of Transportation and the Federal Highway Administration. Volkert. Archived from the original on December 19, 2008. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Inland Docks". Alabama State Port Authority. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- "Demopolis Airport". City of Demopolis. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved June 2, 2011.

- Demopolis, AL Greyhound Station Intercity Bus Service

- "Demopolis city, Alabama: Population Finder". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Demopolis city, Alabama: Census 2000 Demographic Profile Highlights". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Archived from the original on February 12, 2020. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Demopolis City Audit for September 30, 2009" (PDF). LeCroy, Hunter, and Company, P.C. City of Demopolis. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 7, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "United States Census 1930". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved June 2, 2011. (Zipped PDF file, 321 MB)

- "United States Census 1940". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved June 2, 2011. (Zipped PDF file, 168 MB)

- "United States Census 1950". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved June 2, 2011. (Zipped PDF file, 83 MB)

- "United States Census 1960". United States Census Bureau. United States Department of Commerce. Retrieved June 2, 2011. (Zipped PDF file, 103 MB)

- "Annual Estimates of the Resident Population: April 1, 2010 to July 1, 2013". Archived from the original on May 22, 2014. Retrieved June 3, 2014.

- https://demopolisal.org/government/

- "City Government". City of Demopolis. Archived from the original on July 21, 2011. Retrieved May 31, 2011.

- "Gaineswood". Alabama Historical Commission. Archived from the original on August 27, 2007. Retrieved January 23, 2008.

- Marengo County Heritage Book Committee: The heritage of Marengo County, Alabama, page 15. Clanton, Alabama: Heritage Publishing Consultants, 2000. ISBN 1-891647-58-X

- "Giuseppe Moretti". Encyclopedia of Alabama. Auburn University. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- "Alabama: Marengo County". "National Register of Historic Places". Retrieved January 23, 2007.

- "Demopolis Stories of Hellman and Wyler". The Hellman Wyler Festival. 2009. Archived from the original on July 28, 2011. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- "Demopolis: Lillian Hellman". Southern Literary Trail. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- Jason Cannon (March 23, 2011). "Local women's history celebrated". The Demopolis Times. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- "The Fighting Kentuckian (1949)". Historical Movies in Chronological Order. Vernon Johns Society. Retrieved May 28, 2011.

- ""Alabama Story": A New Play About Books, Race, Censorship and the American Character". By Kenneth Jones. January 2, 2020. Retrieved January 29, 2020.

- Climate Summary for Demopolis, Alabama

Bibliography

- Demopolis Chamber of Commerce. 1965. The Story of Demopolis a condensed history of the founding and development of Demopolis, Alabama. Demopolis, Ala: The Chamber.

- Martin, Thomas. 1937. French military adventurers in Alabama, 1818–1828. Princeton University Press.

- Smith, Winston. 2003. The people's city the glory and grief of an Alabama town, 1850–1874. Demopolis, Ala: Marengo County Historical Society.

- Whitfield, Gaius. 1904. The French Grant in Alabama: A History of the Founding of Demopolis. Historical Papers, 1st-2d Ser.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Demopolis, Alabama. |