Morris Canal

The Morris Canal (1829–1924) was a 107-mile (172-km) common carrier coal canal across northern New Jersey in the United States that connected the two industrial canals at Easton, Pennsylvania, across the Delaware River from its western terminus at Phillipsburg, New Jersey, to New York Harbor and the New York City markets via its eastern terminals in Newark and on the Hudson River in Jersey City, New Jersey. (The canal was sometimes called the Morris and Essex Canal,[2] in error, due to confusion with the nearby and unrelated Morris and Essex Railroad.)

| Morris Canal | |

|---|---|

Lock 3 West at Waterloo Village | |

1827 Map of the canal | |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 107 miles (172 km) |

| Maximum boat length | 87 ft 6 in (26.67 m) |

| Maximum boat beam | 10 ft 6 in (3.20 m) |

| Locks | 23 locks + 23 inclined planes |

| Maximum height above sea level | 914 ft (279 m) |

| Status | Closed |

| History | |

| Original owner | Morris Canal and Banking Company |

| Principal engineer | Ephraim Beach |

| Other engineer(s) | James Renwick, David Bates Douglass |

| Date of act | December 31, 1824 |

| Construction began | 1825 |

| Date of first use | 1829 |

| Date completed | May 20, 1832 |

| Date closed | 1924 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Phillipsburg, NJ (Cable Ferry connected across the Delaware to the Lehigh and Delaware Canal's river gate lock.) |

| End point | Jersey City, NJ (originally Newark, NJ) |

| Connects to | Lehigh Canal |

Morris Canal | |

| Location | Irregular line beginning at Phillipsburg and ending at Jersey City |

| NRHP reference No. | 74002228[1] |

| Added to NRHP | October 1, 1974 |

| Morris Canal Route Map (1871) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

With a total elevation change of more than 900 feet (270 m), the canal was considered an ingenious technological marvel for its use of water-driven inclined planes, the first in the United States, to cross the northern New Jersey hills.[lower-alpha 1]

It was built primarily to move coal to industrializing eastern cities that had stripped their environs of wood.[3][lower-alpha 2] Completed to Newark in 1831, the canal was extended eastward to Jersey City between 1834 and 1836. In 1839, hot blast technology was married to blast furnaces fired entirely using anthracite, allowing the continuous high-volume production of plentiful anthracite pig iron.[6]

The Morris Canal eased the transportation of anthracite from Pennsylvania's Lehigh Valley to northern New Jersey's growing iron industry and other developing industries adopting steam power in New Jersey and the New York City area. It also carried minerals and iron ore westward to blast furnaces in western New Jersey and eastern Pennsylvania (famously, Allentown and Bethlehem) until the development of Great Lakes iron ore caused the trade to decline.

The Morris Canal remained in heavy use through the 1860s. But railroads had begun to eclipse canals in the United States, and in 1871, it was leased to the Lehigh Valley Railroad.

Like many enterprises that depended on anthracite, the canal's revenues dried up with the rise of oil fuels and truck transport. It was taken over by the state of New Jersey in 1922, and formally abandoned in 1924.

Although it was largely dismantled in the following five years, portions of the canal and its accompanying feeders and ponds are preserved. A statewide greenway for cyclists and pedestrians is planned, beginning in Phillipsburg, traversing Warren, Sussex, Morris, Passaic, Essex and Hudson Counties and including the old route through Jersey City.[7] The canal was added to the National Register of Historic Places on October 1, 1974 for its significance in engineering, industry, and transportation.[8]

Description

On the canal's western end, at Phillipsburg, a cable ferry allowed Morris Canal boats to cross the Delaware River westward to Easton, Pennsylvania, and travel up the Lehigh Canal to Mauch Chunk, in the anthracite coal regions, to receive their cargoes from the mines. From Phillipsburg, the Morris Canal ran eastward through the valley of the Musconetcong River, which it roughly paralleled upstream to its source at Lake Hopatcong, New Jersey's largest lake. From the lake the canal descended through the valley of the Rockaway River to Boonton, eventually around the northern end of Paterson's Garret Mountain, and south to its 1831 terminus at Newark on the Passaic River. From there it continued eastward across Kearny Point and through Jersey City to the Hudson River. The extension through Jersey City was at sea level and was supplied with water from the lower Hackensack River.

With its two navigable feeders, the canal was 107 mi (172 km) long. Its ascent eastward from Phillipsburg to its feeder from Lake Hopatcong was 760 ft (230 m), and the descent from there to tidewater was 914 ft (279 m). Surmounting the height difference was considered a major engineering feat of its day, accomplished through 23 locks and 23 inclined planes — essentially, short railways that carried canal boats in open cars uphill and downhill using water-powered winches. Inclined planes required less time and water than locks, although they were more expensive to build and maintain.

History

The idea for constructing the canal is credited to Morristown businessman George P. MacCulloch, who reportedly conceived the idea while visiting Lake Hopatcong. In 1822, MacCulloch brought together a group of interested citizens at Morristown to discuss the idea.

The Palladium of Liberty, a Morristown newspaper of the day, reported on August 29, 1822: "...Membership of a committee which studied the practicality of a canal from Pennsylvania to Newark, New Jersey, consisted of two prominent citizens from each county (NJ) concerned: Hunterdon County, Nathaniel Saxton, Henry Dusenberry; Sussex County, Morris Robinson, Gamaliel Bartlett; Morris County, Lewis Condict, Mahlon Dickerson; Essex County, Gerald Rutgers, Charles Kinsey; Bergen County, John Rutherford, William Colefax ...".

On November 15, 1822, the New Jersey Legislature passed an act appointing three commissioners, one of whom was MacCulloch, to explore the feasibility of the project, determine the canal's possible route, and estimate its costs. MacCulloch initially greatly underestimated the height difference between the Passaic and Lake Hopatcong, pegging it at only 185 ft (56 m).

On December 31, 1824, the New Jersey Legislature chartered the Morris Canal and Banking Company, a private corporation charged with the construction of the canal. The corporation issued 20,000 shares of stock at $100 a share, providing $2 million of capital, divided evenly between funds for building the canal and funds for banking privileges. The charter provided that New Jersey could take over the canal at the end of 99 years. In the event that the state did not take over the canal, the charter would remain in effect for 50 years more, after which the canal would become the property of the state without cost.

Construction

In 1823, the canal company hired Ephraim Beach, who was originally an assistant engineer on the Erie Canal, as its chief engineer, to survey the routes for the Morris Canal.[9] Construction started in 1824 in Newark, with a channel 31 feet (9.4 m) wide and 4 feet (1.2 m) deep. The canal started from Upper Newark Bay, followed the Passaic River and crossed it at Little Falls, then went on to Boonton, Dover, then the southern tip of Lake Hopatcong, whereupon it went to Phillipsburg.[10]

On October 15, 1825, ground was broken at the summit level at the "Great Pond" (i.e. lake Hopatcong). By 1828, 82 of the 97 eastern sections and 43 of the 74 western sections were finished. By 1829, some sections were completed and opened for traffic, and in 1830, the 38-mile (61 km) section from Newark to Rockaway was opened.[11]

Because the locks could only handle boats of 25 long tons (25 t), that meant that through traffic from the Lehigh Canal was impossible, requiring reloading coal at Easton.[12]

Design and building of the inclined planes

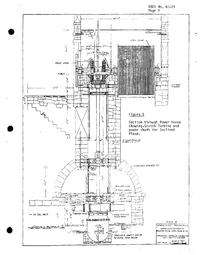

.tiff.jpg)

The vertical movement on the Morris Canal 1,672 feet (510 m) was 18 feet per mile (3.4 m/km), in comparison with less than 1 foot per mile (19 cm/km) on the Erie Canal, and would have required a lock every 2 miles (3.2 km), which would have made the costs prohibitive.[13] James Renwick, a professor at Columbia University, devised the idea of using inclined planes to raise the boats 1,600 feet (490 m) in 90 miles (140 km), instead of using about 300 lift locks, since a lift lock of that time typically lifted about 6 feet (1.8 m).[14] In the end, Renwick used only 23 inclined planes and 23 locks.[12] Lock dimensions were originally 9 feet (2.7 m) wide and 75 feet (23 m) long[15]

Renwick's original design seems to have been to have double tracks on all inclined planes, with the descending caisson holding more water; thus, the system theoretically would not have needed external power.[16] Nevertheless, the inclined planes were built with overshot water wheels to supply power.[16]

The early planes were done by different contractors, and differed greatly. In 1829, the canal company hired David Bates Douglass from West Point, who became the chief engineer of the planes. He supervised the construction of the remaining planes to be built, and also altered the already built planes.[9]

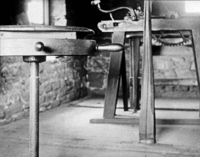

The inclined planes had a set of tracks, gauge about 12 1⁄2 feet (3.8 m), running from the lower level up the incline, over the crest of the hill at the top, and down into the next level. Tracks were submerged at both ends. A large cradle, holding the boat, ran on the tracks.[17] Iron overshot waterwheels originally powered the planes.[18]

The Scotch (reaction) turbines, which later replaced the overshot water wheels, were 12 1⁄2 feet (3.8 m) feet in diameter and made of cast iron. They could pull boats up an 11% grade. The longest plane was the double-tracked Plane 9 West, which was 1,510 feet (460 m) long and lifted boats 100 feet (30 m) up (i.e. 6% grade) in 12 minutes.[15] The total weight of the boat, cargo, and cradle was about 110–125 long tons (112–127 t).[15]

The Scotch turbines produced (for example, on Plane 2 West) 235 horsepower using a 45-foot (14 m) head of water and had a discharge rate of 1,000 cubic feet (28 m3) per minute. Some turbines were also reported to develop 704 horsepower.[19] The winding drum was 12 feet (3.7 m) in diameter and had a spiral grove of 3 inches (76 mm) pitch. The rope was fastened on both ends to the drum, and there was a clutch that allowed the direction of the wheel to be reversed. The plane had two lines of steel rails, with a gauge of 12 feet 4½ inches (3.76 m) from center of rail to center. Rails were 3⅛ inches (7.9 cm) wide at top and 3½ inches (8.89 cm) high, and weighed 76 lbs/yard (37.7 kg/m). The cradle had a brake, in case the load went downhill too fast. Descent was also checked by the plane-man by putting about half power through the turbine.[20] The water was fed into the turbines from below, thus relieving friction on the bearings and balancing them.

A comparison of Plane 2 West (Stanhope), which had a 72-foot (22 m) lift, with a flight of 12 locks yields the following: the plane took 5 minutes 30 seconds, and consumed 3,180 cubic feet (90 m3) of water lifting a loaded boat. Locks 95 by 11 by 6 feet (29.0 m × 3.4 m × 1.8 m), meaning 6,270 cubic feet (178 m3) of water per lock) would consume 72,240 cubic feet (2,046 m3) for 12 locks (about 23 times more water) and would take 96 minutes.[20]

The Elbląg Canal, one of Seven Wonders of Poland, used the Morris Canal's technology as inspiration for its inclined planes; for that reason, the inclined planes on that canal strongly resemble those on the Morris Canal.[20]

The Newark Eagle reported in 1830:

The machinery was set in motion under the direction of Major Douglass, the enterprising Engineer. The boat, with two hundred persons on board, rose majestically out of the water; in one minute it was upon the summit, which it passed apparently with all the ease that a ship would cross a wave of the sea. As the forward wheels of the car commenced their descent, the boat seemed gently to bow to the spectators and the town below, then glided quickly down the wooden way. In six minutes and thirty seconds it descended from the summit and re-entered the canal, thus passing a plane one thousand and forty feet long, with a descent of seventy feet, in six and one half minutes.[21]

Orange Street Inclined Plane

In 1902, after a fatal crash between the Delaware and Lackawanna railroad and an automobile, the railroad grade was lowered (to the level it occupies today) and the Morris Canal had to make an electric driven incline plane to bring boats up and over the railroad and Orange street, and then back down into the canal, with a pipe to carry the water across the break.[22]

Aqueducts

Several aqueducts were built for the canal: the 80-foot (24 m) Little Falls Aqueduct over the Passaic River in Paterson, New Jersey, and the 236-foot (72 m) Pompton River Aqueduct,[15] as well as aqueducts over the Second and Third river [23]

The longest level was 17 miles (27 km), from Bloomfield to Lincoln Park; the second-longest, 11 miles (18 km) from Port Murray to Saxon Falls.[15]

The aqueduct over the Pohatcong Creek at the base of Inclined Plane 7 West is now used as a road bridge on Plane Hill Road in Bowerstown.[24]

Opening of the canal

On November 1, 1830, before the whole canal was finished, the eastern side of the canal between Dover and Newark was tested with several boats loaded with iron ore and iron. These went through the planes without incident.[12] On May 20, 1832, the canal was officially opened.[12] The first boat passing entirely through the canal was the Walk-on-Water,[25] followed by two coal laden boats went from Phillipsburg all the way to Newark.[12] This initial section (not counting the Jersey City portion, which was done later) ran 98.62 miles and cost $2,104,413.[26]

Operating years

Soon after opening, it became apparent that the canal had to be widened and had to be extended across to the New York Bay across Bayonne.[12] Early boats, called "flickers," could only carry 18 tons.[27] By 1840 the company had finished enlarging the locks, canal and planes, and finished building the extension to Jersey City. Boats were divided in two, hitched with a pin, as were the trucks (cradles) on the inclined planes.[28] The enlarged locks' dimensions were now 11 feet (3.4 m) wide and 90 feet (27 m) long.[15]

The original company failed in 1841 amid banking scandals, and the canal was leased to private bidders for three years.[29] The canal company was reorganized in 1844, with a capitalization of $1 million. The canal bed was inspected, and improvements were made. First, the places where seepage occurred were lined with clay, and two feeders were dug, to Lake Hopatcong and to Pompton. The inclined planes were rebuilt with wire cabling.[28] Banking privileges were removed in 1849, leaving the company as a canal-operating business only.[29]

By 1860, the canal had been progressively enlarged to accommodate boats of 70 tons. Traffic reached a peak in 1866, when the canal carried 889,220 long tons (903,490 t) of freight (equivalent to nearly 13,000 boat loads). Between 1848 and 1860, the original overshot water wheels that powered the inclined planes were replaced with more powerful water turbines. The locks and inclines planes were also renumbered, since some had been combined or eliminated.

Boats of 79 long tons (80 t) were now 87 1⁄2 feet (26.7 m) long, 10 1⁄2 feet (3.2 m) wide, and drew 4 1⁄2 feet (1.4 m) of water.[15]

Freight figures are as follows:[30]

| Year | Tonnage | Year | Tonnage | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1845 | 58,259 | 1875 | 491,816 | |

| 1850 | 239,682 | 1880 | 503,486 | |

| 1855 | 553,204 | 1885 | 364,554 | |

| 1860 | 707,631 | 1890 | 394,432 | |

| 1865 | 716,587 | 1895 | 270,931 | |

| 1866 | 889,220 | 1900 | 125,829 | |

| 1870 | 707,572 | 1902 | 27,392 | |

Cargo

The Morris canal carried coal, malleable pig iron,[28] and iron ore. It also carried grain, wood, cider, vinegar, beer, whiskey, bricks, hay, hides, sugar, lumber, manure, lime,[31] and ice. Although it is said that the Morris Canal was mainly a freight canal and not a passenger canal,[28] some boats on the Morris Canal did offer "Cool summer rides accompanied by a shipment of ice".[32] Additional cargo include scrap metal, zinc, sand, clay, and farm products.[33]

Iron ore from the Ogden Mine was brought to Nolan's Point (Lake Hopatcong). In 1880 the canal transported 1,700 boatloads (about 108,000 tons) of iron ore.[15] Thereafter, competition from taconite ore in the Lake Superior region brought a decline in New Jersey bog iron.

Working hours

The plane tender of Plane 11 East reported that during the operating days, boats would tie up at night up to a mile above the plane, down another mile to Lock 15 East (Lock 14 East in the old 1836 numbering), and then about a mile below Lock 14 East. They would start putting boats through starting around 4 a.m. (dawn), and go all day long until 10 p.m., often handling boatmen who had gone through that morning, unloaded in Newark, and were returning.[34]

Decline

The canal's profitability was undermined by railroads, which could deliver in five hours cargo that took four days by boat.[28]

In 1871, the canal was leased by the Lehigh Valley Railroad, which sought the valuable terminal properties at Phillipsburg and Jersey City. The railroad never realized a profit from the operation of the canal.

By the early 20th century, commercial traffic on the canal had become negligible. Two committees, in 1903 and 1912, recommended abandoning the canal.[27] The 1912 survey wrote, "...from Jersey City to Paterson, [the canal] was little more than an open sewer ... but its value beyond Paterson was of great importance, no longer as a freight transit line but as a parkway."[35] Many of the existing photographs of the working canal were shot as part of these surveys, as well as by other people who wanted photographs of the canal before its demise.[27]

In 1918, the canal company filed a lawsuit to block the construction of the Wanaque Reservoir in Passic County, asserting that the reservoir would divert water needed for the Pompton feeder. The company won the suit in 1922, but the victory was Pyrrhic; the canal was now viewed as an impediment to the development of the area's water supply. On March 1, 1923, the state of New Jersey took possession of the canal;[27] it shut it down the following year. Over the next five years, the state largely dismantled the canal: the water was drained out, banks were cut, and canal works destroyed, including needlessly dynamiting the Little Falls aqueduct.[36]

The Newark City Subway, now Newark Light Rail, was built along its route.

Canal today

Portions of the canal are preserved. Waterloo Village, a restored canal town in Sussex County, has the remains of an inclined plane, a guard lock, a watered section of the canal, a canal store, and other period buildings. The Canal Society of New Jersey maintains a museum in the village.

Other remnants and artifacts of the canal can be seen along its former course. On the South Kearny, New Jersey, peninsula, where the canal ran just south of and parallel to the Lincoln Highway, now U.S. Route 1/9 Truck, the cross-highway bridges for Central Avenue and the rail spur immediately to its east were built to span the highway and the canal,[37] resulting in spans that today seem unnecessarily long.

The inlet where the canal connected to the Hudson River is now the north edge of Liberty State Park.

Morris Canal Greenway

The North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority is developing the Morris Canal Greenway, a group of passive recreation parks and preserves along parts of the former canal route.[38][39][40][41]

Parks along the greenway include:

- Peckman Preserve

- Pompton Aquatic Park

- Wayne Township Riverside Park

- Walking path in Lincoln Park

Gallery

.jpg) Delaware River Portal, canal entrance, Phillipsburg

Delaware River Portal, canal entrance, Phillipsburg- Lock 3 West, Waterloo Village

Foundation of the Lock Tender's House at Lock 7 West, the "Bread Lock"

Foundation of the Lock Tender's House at Lock 7 West, the "Bread Lock" Aqueduct over the Pohatcong Creek by Inclined Plane 7 West, Bowerstown

Aqueduct over the Pohatcong Creek by Inclined Plane 7 West, Bowerstown Sleeper stones from Inclined Plane 7 West used as base of retaining wall

Sleeper stones from Inclined Plane 7 West used as base of retaining wall Tailrace tunnel at Inclined Plane 9 West, Port Warren

Tailrace tunnel at Inclined Plane 9 West, Port Warren Remains of Inclined Plane 2 East near Ledgewood

Remains of Inclined Plane 2 East near Ledgewood

Historic images of the canal in operation

Inclined Plane 9 West, Port Warren, the longest plane, raising boats 100'. This is one of three double-tracked planes allowing boats to ascend and descend at the same time. The other double-tracked planes are 6 West (Port Colden) and 12 East (Newark).

Inclined Plane 9 West, Port Warren, the longest plane, raising boats 100'. This is one of three double-tracked planes allowing boats to ascend and descend at the same time. The other double-tracked planes are 6 West (Port Colden) and 12 East (Newark)..jpg) Canal near Waterloo, possibly Lock 3W. Note snubbing post to left of lock, to stop boats.

Canal near Waterloo, possibly Lock 3W. Note snubbing post to left of lock, to stop boats. Summit level at Lake Hopatcong.

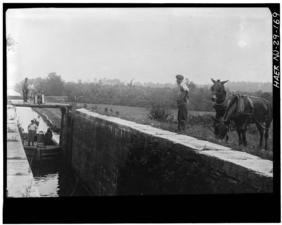

Summit level at Lake Hopatcong. Lock 1 East. Note mule team.

Lock 1 East. Note mule team. Tailrace of Plane 2 East. Water from turbine comes out from the left. Water on the right is from the bypass flume.

Tailrace of Plane 2 East. Water from turbine comes out from the left. Water on the right is from the bypass flume. Maintenance work on Plane 5 East, digging out silt from canal prism.

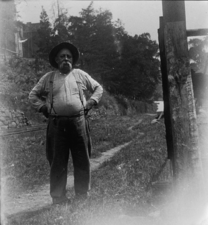

Maintenance work on Plane 5 East, digging out silt from canal prism. Canal Tender at Plane 7 East.

Canal Tender at Plane 7 East. Boat coming at top of inclined plane.

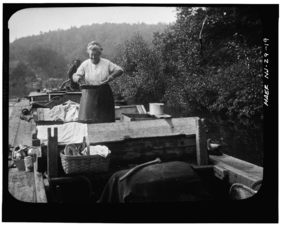

Boat coming at top of inclined plane. Canal boat cook.

Canal boat cook. Girl operating machinery on lock.

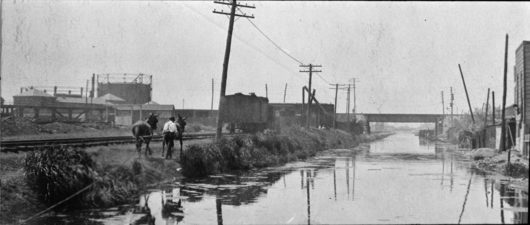

Girl operating machinery on lock. Going through Paterson, New Jersey

Going through Paterson, New Jersey Inclined Plane 12 East, in Newark, New Jersey at High st. This is the third double-tracked plane. This spot would be Raymond Blvd around University Heights, looking east towards Martin Luther King Jr. St.

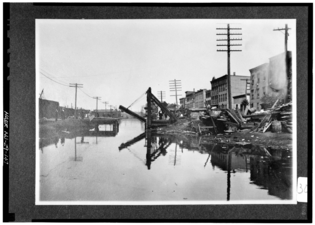

Inclined Plane 12 East, in Newark, New Jersey at High st. This is the third double-tracked plane. This spot would be Raymond Blvd around University Heights, looking east towards Martin Luther King Jr. St. Canal at Broad Street in Newark, New Jersey, facing west.

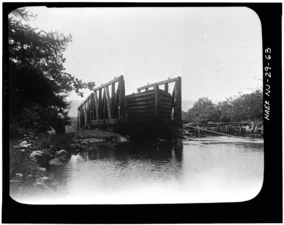

Canal at Broad Street in Newark, New Jersey, facing west. Lift bridge at Grove Street in Jersey City, New Jersey.

Lift bridge at Grove Street in Jersey City, New Jersey.

See also

- Pequannoc Spillway

- Pompton dam

- Waterloo Village

- Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule II

- Henry Barnard Kümmel

- Delaware Canal - A canal feeding urban Philadelphia connecting with the Morris and Lehigh Canals at their respective Easton terminals.

- Delaware and Raritan Canal – A later New Jersey canal carrying mostly coal from the Delaware river to New York and northeastern New Jersey, and iron ore from New Jersey up the Lehigh.

- Chesapeake and Delaware Canal – A canal crossing the Delmarva Peninsula in the states of Delaware and Maryland, connecting the Chesapeake Bay with the Delaware Bay.

- Delaware and Hudson Canal - Another early built coal canal as the American canal age began; contemporary with the Lehigh and the Schuylkill navigations.

- Lehigh Canal – A sister canal in the Lehigh Valley that fed coal traffic to the Delaware Canal via a connection in Easton, Pennsylvania.[lower-alpha 3]

- Schuylkill Canal - Navigation joining Reading, PA and Philadelphia.[lower-alpha 4]

- Paterson Great Falls

- Lake Hopatcong

General references

- Goller, Robert (1999). The Morris Canal, Across New Jersey by Water and Rail (First ed.). Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0738500768.

Notes

- Massachusetts Middlesex Canal (1793-1808), the Lehigh Canal's 1st successes (1819,1820-1824), and New York's 1stErie Canal sections (1821) had inspired industrialists and merchants in Baltimore and Pennsylvania to look for a way west, and better ways to travel faster. In and near most major settlements by the 1790s, home owners and industrialists were looking for reachable wood stands or charcoal for heat and metalworking.[3] In fuel-desperate Philadelphia, industrialist Josiah White, whose employees had developed a technique for getting anthracite to ignite and burn, proposed a navigation canal along the Lehigh River in 1814-15, later known as the Lehigh Canal. This feat, along with his involvement with the (less spectacularly successful) Schuylkill Canal inspired business interests along the entire eastern seaboard to think anthracite, and think bigger.

- Josiah White also spearheaded using Anthracite in a blast furnace to smelt anthracite pig iron at the Lehigh Crane Iron Works, an 1839 subsidiary of Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company (LC&N Co.) that began casting pig iron on July 4, 1840. Ores from Sussex and Morris County, New Jersey, flowed across the Delaware from New Jersey and up the Lehigh to his furnaces at Catasauqua, Pennsylvania (above Allentown)[4][5] The canal fostered the growth of Allentown and Bethlehem.

- If the Lehigh Canal hadn't been built, the other Canals reaching the Delaware would likely have had nothing worth the expense to ship, so excepting the Delaware and Hudson Canal which was a similar venture to the Lehigh in that it reached deep right up to the coal sources, their investment would likely never have happened. The principle customer of the Delaware Canal was the coal barges coming down the Lehigh shipped by Lehigh Coal & Navigation Company, which also came to manage the Delaware Canal into the 1960s.

- The Schuylkill Canal was long delayed by investors quarreling over the best way to proceed. Disgusted, White and Hazard explored tapping Anthracite via the Lehigh, and ended up incorporating the Lehigh Coal and Navigation Company which spearheaded many technological initiatives.

References

- "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- Drago, Harry Sinclair (1972). Canal Days in America, The History and Romance of Old Towpaths and Waterways. New York: Clarkson N. Potter, Inc. ISBN 0-517-500876. p. 112, 117. Here are two cases in a historical book where it's confusingly called the Morris and Essex Canal in the two photo captions, but for the chapter, and in the main text, it's called the Morris Canal (p. 111 ff).

- James E. Held (July 1, 1998). "The Canal Age". Archaeology (online). A publication of the Archaeological Institute of America (July 1, 1998). Retrieved June 12, 2016.

On the settled eastern seaboard, forest decimation created an energy crisis for coastal cities, but the lack of water- and roadways made English coal shipped across the Atlantic cheaper in Philadelphia than Pennsylvania anthracite mined 100 miles away. ... George Washington, Benjamin Franklin, and other founding fathers believed they were the key to the New World's future.

- Fred Brenckman, Official Commonwealth Historian (1884). History of Carbon County Pennsylvania (627 pages, Archive.org project PDF e-reprint, (1913) 2nd ed.). Also Containing a Separate Account of the Several Boroughs and Townships in the County, J. Nungesser, Harrisburg, PA.

- LEHIGH VALLEY RAILROAD Guide Book, The Hopkin Thomas Project.

- Brenckman, Chapter II - Improvements.

- Morris Canal Greenway Plan North Jersey Transportation Planning Authority

- Kalata, Barbara (October 10, 1973). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Morris Canal". National Park Service. With 25 accompanying photos

- Goller p.12

- Drago p. 116

- Clement, Dan (1983). Historical American Engineering Record, NJ-29 Morris Canal (PDF). Washington, D.C.: National Park Service, Department of the Interior. Retrieved February 18, 2014. P. 3

- Drago, p. 119

- HAER NJ-29 p. 4

- Drago gives this figure of 6 feet on p. 119, although many canals had locks with a lift of 8 feet, e.g. the Chesapeake and Ohio Canal, which has some locks with a lift of 10 feet.

- Canal Society of New Jersey. "Morris Canal Fact Sheet: Planes, Canals, Boats, and other information" (PDF). Retrieved February 5, 2014.

- Goller p. 11

- HAER NJ-29 p. 5

- HAER NJ-29 p. 6

- Kirby, Richard Shelton (1990). Engineering in History. Courier Dover Publications. p. 215. ISBN 0486264122.

- "Railroad Extra, the Morris Canal and its Inclined Planes". Retrieved February 6, 2014.

- Stuart, Charles Beebe (1871). "Major David Bates Douglass". Lives and Works of Civil and Military Engineers of America. New York: D. Van Nostrand. p. 207. Retrieved January 26, 2013.

- Goller, p. 101. Note that Goeller's description in the book is incorrect: the railroad does NOT pass under Orange street, but rather, runs alongside just to the north of Orange Street, and does not cross it. At the juncture it is below the grade level of Orange Street, but both to the east and west, it is now elevated (above grade).

- Goeller p. 100

- Bertland, Dennis N. (July 1995). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory/Nomination: Bowerstown Historic District". National Park Service. With accompanying 21 photos

- Harlow, Alvin F. (1926). Old Towpaths, The Story of The American Canal Era. New York & London: D Appleton & Co. p. 197.

- HAER NJ-29, P. 3

- Goller p. 8

- Drago p. 120

- Goller p.7

- HAER NJ-29, P. 6

- Lee, James. "Morris Canal NJ History". Retrieved January 17, 2014.

- Sloan, Eric (1955). Our Vanishing Landscape. New York: Ballantine Books, Random House. p. 57. ISBN 0-345-24293-9.

- HAER NJ-29 P. 6

- Old Towpaths, p.316

- HAER NJ-29, P. 7

- Drago p. 123-124

- Kearny Yard

- "Official site". Morris Canal Greenway. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- "Official site". Warren County Morris Canal Greenway. Retrieved September 3, 2015.

- "Passaic County, NJ - Official Website - Morris Canal Greenway Project". www.passaiccountynj.org. Retrieved February 23, 2017.

- O'Neill, James M. (November 26, 2017). "Morris Canal: A century after its demise, 102-mile watery relic is reborn with new role: Shreds of the old Morris Canal that somehow avoided destruction are being restored as hiking trails and bike routes across six North Jersey counties". NorthJersey.com. Retrieved November 27, 2017.

Further reading

- Macasek, Joseph J. (1997). Guide to the Morris Canal in Morris County (Second ed.). Morris County Heritage Commission.

- Lee, James (1979). The Morris Canal – A Photographic History (Enlarged Revised ed.). Delaware Press.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Morris Canal. |

- Canal Society of New Jersey, includes canal map

- http://planning.morriscountynj.gov/survey/canal/ a partial listing of Canal employees in Morris County, New Jersey

- Historic American Engineering Record (HAER) No. NJ-29, "Morris Canal, Phillipsburg"

- HAER No. NJ-29-A, "Morris Canal, Delaware River Portal"

- HAER No. NJ-29-B, "Morris Canal, Hotel"

- HAER No. NJ-29-C, "Morris Canal, Spillway"

- HAER No. NJ-29-D, "Morris Canal, Inclined Plane 9 West"

- HAER No. NJ-29-E, "Morris Canal, Stewartsville"

- HAER No. NJ-29-F, "Morris Canal, Greene's Mill Vicinity"

- HAER No. NJ-29-G, "Morris Canal, Washington"

- HAER No. NJ-29-H, "Morris Canal, Rockport"

- HAER No. NJ-29-I, "Morris Canal, Guard Lock 5 West"

- HAER No. NJ-29-J, "Morris Canal, Waterloo"

- HAER No. NJ-29-K, "Morris Canal, Cassedy's Store"

- HAER No. NJ-29-L, "Morris Canal, Scotch Turbine"

- HAER No. NJ-30, "Morris Canal, Inclined Plane 10 West"

- Walking The Morris Canal

- Photo Documentary of the Morris Canal

- The Morris Canal in Bloomfield, NJ

- The Morris Canal in Roxbury Township, NJ

- National Register of Historic Places nomination form, and accompanying photos