Crystal Palace Park

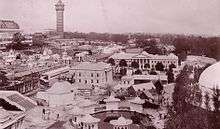

Crystal Palace Park is a Victorian pleasure ground located in the south-east London suburb of Crystal Palace which surrounds the site of the former Crystal Palace Exhibition building. The Palace had been relocated from Hyde Park, London after the 1851 Great Exhibition and rebuilt with some modifications and enlargements to form the centrepiece of the pleasure ground, before being destroyed by fire in 1936. The park features full-scale models of dinosaurs in a landscape, a maze, lakes, and a concert bowl.[1]

| Crystal Palace Park | |

|---|---|

Crystal Palace Park | |

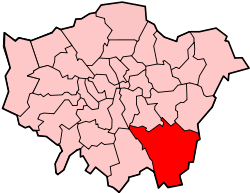

Location of the park shown within content of Greater London | |

| Type | Public park |

| Location | Crystal Palace London, SE19 United Kingdom |

| Coordinates | 51°25′13″N 0°04′14″W |

| Area | 200 acres (81 ha) |

| Created | 1854 |

| Operated by | London Borough of Bromley |

| Status | Open all year |

| Public transit access | |

| Website | crystalpalacepark |

This site contains the National Sports Centre, previously a football stadium that hosted the FA Cup Final from 1895 to 1914 as well as Crystal Palace F.C.'s matches from their formation in 1905 until the club was forced to relocate during the First World War. The London County Cricket Club also played matches at Crystal Palace Park Cricket Ground from 1900 to 1908, when they folded, and the cricket ground staged a number of other first-class cricket matches and had first been used by Kent County Cricket Club as a first-class venue in 1864.

The park is situated halfway along the Norwood Ridge at one of its highest points. This ridge offers views northward to central London, eastward to the Queen Elizabeth II Bridge and Greenwich, and southward to Croydon and the North Downs. The park remains a major London public park. The park was maintained by the LCC and later the GLC, but with the abolition of the GLC in 1986, control of the park was given to the London Borough of Bromley, so the park is now entirely within the London Borough of Bromley.

The park is Grade II* listed on the Register of Historic Parks and Gardens.[2]

History

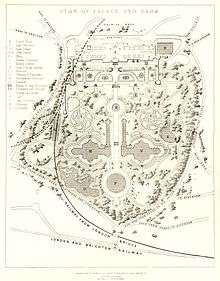

After the 1851 Great Exhibition in Hyde Park, Joseph Paxton appealed for the retention of The Crystal Palace in Hyde Park, but the government decreed that the Palace be removed. Paxton formed the Crystal Palace Company to purchase the Hyde Park Crystal Palace for £70,000, as well as a new site at the summit of Sydenham Hill in Kent for the construction of an enlarged Crystal Palace which cost a total of £1.3 million.[3] The 389-acre site consisted of woodland and the grounds of the mansion known as Penge Place owned by Paxton's friend and railway entrepreneur Leo Schuster.[4] This land as enclosed in the early 19th century previously made up the northern part of Penge Common, a large area of wood pasture which abutted the Great North Wood. Between 1852 and 1854, an enlarged and redesigned Crystal Palace was rebuilt at the new site, set in a park constructed by Sir Joseph Paxton's Crystal Palace Company.[5]

The development of ground and gardens of the park (which straddled the border between Surrey and Kent[6]) cost considerably more than the rebuilt Crystal Palace. Edward Milner designed the Italian Garden and fountains, the Great Maze, and the English Landscape Garden, and Raffaele Monti was hired to design and build much of the external statuary around the fountain basins, and the urns, tazzas and vases.[7] The series of fountains constructed required the building of two 284 ft (87 m) high water towers, designed by Isambard Kingdom Brunel, at either end of the palace.[8] The sculptor Benjamin Waterhouse Hawkins was commissioned to make 33 lifesized models, completed in 1854, of the (then) newly discovered dinosaurs and other extinct animals in the park.[9] The park was also given a gift of a megatherium skull by Charles Darwin. The rebuilt Crystal Palace was opened by Queen Victoria in June 1854.

Rail access to the park became possible when the Crystal Palace railway station opened in 1854. In 1864, Thomas Webster Rammell experimented with a 600-yard pneumatic railway in the tunnel between the Sydenham and Penge gates to the park.[10] In 1865, another station, the Crystal Palace (High Level) railway station opened, but this station closed in 1954.[11]

The park has been used for various sporting activities from its early days. The Crystal Palace Park Cricket Ground was created on the site in 1857. In 1894, the two largest fountains were grassed over and the south basin was converted to a football stadium in 1895.[7] The stadium was used to host FA Cup Finals for 20 years starting with the 1895 FA Cup Final until 1914. Crystal Palace F.C. also played their home games at the stadium from 1905 to 1915.

In 1911, the Festival of Empire was held at the park and the park was transformed with buildings designed to represent the British Empire. Many of these buildings remained at the site until the 1940s.[5]

In 1936, The Crystal Palace was destroyed by fire.[12] The south water tower was demolished soon afterwards due to fire damage. The north water tower was demolished in 1941, perhaps to eliminate landmarks that German bombers might use to orient themselves during air raids in the Second World War.[13]

A 400 ft-long Marine Aquarium was built in 1872 on a part of The Crystal Palace site left vacant after a fire in 1866, but it was not a financial success. A large section of it was destroyed during the demolition of the north water tower. The Crystal Palace transmitting station was built on part of the site of the aquarium in the 1950s.[14]

The park also housed one of the pioneer speedway tracks, which opened for business in 1928. The Crystal Palace Glaziers raced in the Southern and National Leagues up to 1933 when the promotion moved on to a track in New Cross. The extensive grounds were used in pre-war days for motorcycle racing and, after the 1950s, for motorcar racing; this was known as the Crystal Palace circuit. Large sections of the track layout still remain as access roads around the park. The circuit itself fell into disuse after the final race in 1972, although it has been digitally recreated in the Grand Prix Legends racing simulation and 2010 sees the 10 years of campaigning work to reopen the track culminating in Motorsport at the Palace.[15]

The National Sports Centre (NSC) was built in 1964 on the old football ground. In 2005 the Mayor of London and the London Development Agency (LDA) took control of the NSC as part of London's bid for the 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics, and it is now managed by Greenwich Leisure on their behalf. The park also once housed a ski slope.[16]

After the abolition of the Greater London Council, the ownership of the park was transferred to London Borough of Bromley in 1986, which oversaw a number of restoration works on the site. A third of the park was restored between 2001 and 2003, including the dinosaur figures.[17]

Sites of interest

The park contains a large bust of Sir Joseph Paxton, first unveiled in 1873. It was sculpted by William F. Woodington, and was originally located looking towards the Palace building over the central pool on the Grand Central Walk.

The Italian Terraces with their sculptures survive from the destroyed Crystal Palace.[8] The upper and lower terraces are linked by flights of steps with sphinxes flanking each flight.[18]

The Crystal Palace Dinosaurs, a group of sculptures of dinosaurs and extinct mammals complete with a 'geological' landscape, are in and around the 'tidal lake' at the southeast side of the park.

A statue of Guy the Gorilla by the sculptor David Wynne was erected in Crystal Palace Park in 1961.[19]

The park contains a free maze. The maze is 160 ft in diameter and occupies a total area of nearly 2000 square yards. The maze was first created around 1870, and it was one of the largest mazes in the country. It later fell into disrepair but was replanted in 1987 by the London Borough of Bromley. In 2009, an artwork was set within the maze, which was restored to celebrate the centenary of the Girl Guide movement. A notice by the entrance to the maze informs of the park's link to the founding of the Girl Guides:[20][21]

In 1909 during a Boy Scout rally held in the park a group of girls approached Lord Robert Baden Powell to demand the formation of a similar movement for girls. Baden Powell responded positively to the request and shortly afterwards published his Scheme for Girl Guides. Six thousand girls joined when the organisation was founded in 1910.

— Inscription in the park by the entrance to the maze

In northern corner of the park is the Crystal Palace Bowl, a natural amphitheatre where largescale open-air summer concerts have been held since the 1960s. These have ranged from classical and orchestral music, to rock, pop, blues and reggae. The likes of Pink Floyd, Bob Marley, Elton John, Eric Clapton and the Beach Boys all played the Bowl during its heyday. The stage was rebuilt in 1997 with an award-winning permanent structure designed by Ian Ritchie.,[22] which was nominated for the prestigious RIBA Stirling Prize.

The Bowl has been inactive as a music venue for several years and the stage has fallen into a state of disrepair, but as of March 2020 London Borough of Bromley Council are working with a local action group to find “creative and community-minded business proposals to reactivate the cherished concert platform”.[23]

A World War I memorial bell is placed in the park. Crystal Palace was once used as a training ground for the Royal Navy, and was referred to as H.M.S. Victory VI. The bell was originally unveiled in 1931 on the terrace in the park (the location was called the "quarterdeck"), but moved to the present location in the 1970s.[24]

The Crystal Palace Museum is housed in the only surviving building constructed by the Crystal Palace Company built circa 1880 as a classroom for the Crystal Palace Company's School of Practical Engineering.[25]

The park is one of the starting points for the Green Chain Walk, linking to places such as Chislehurst, Erith, the Thames Barrier and Thamesmead. Section 3 of the Capital Ring walk round London goes through the park.[26]

Proposed developments

A number of proposals to redevelop the Crystal Palace Park have been put forward since the 1980s. The park was handed to the London Borough of Bromley after the abolition of the Greater London Council in 1986, and a long-fought-over local issue is whether to build on the open space which was the location of the original Crystal Palace building or to leave it as parkland as the Greater London Council had done. In 1989 Bromley proposed the development of the site for hotel and leisure purposes, it culminated in the passing by the House of Commons of the Bromley London Borough Council (Crystal Palace) Act 1990, which limits development on the site.[27][28]

In 1997, a planning proposal was submitted which involved 53,000 square metres of leisure floor space, including a 20-screen multiplex. The proposal was opposed by a local campaign group, the Crystal Palace Campaign, set up a month later.[29]

In 2003, plan for a modern building in glass was submitted to the Bromley council.[30]

In 2007, a £67 million master plan was drawn up by London Development Agency which includes the building of a new sports centre, the creation of a tree canopy to mimic the outline of the palace, the restoration of the Paxton Axis walkway through the park, but it also included a controversial proposal for housing on two parts of the park.[31] It won government backing in 2010, and the plans were upheld by the High Court in 2012 after a challenge by a local group, the Crystal Palace Community Association.[32][33]

In January 2011 the owners of Crystal Palace F.C. announced plans to relocate the club back to the site of the NSC from their current Selhurst Park home, redeveloping it into a 25,000-seater, purpose-built football stadium.[34] However Tottenham Hotspur F.C. also released plans to redevelop the NSC into a 25,000-seater stadium, maintaining it as an athletics stadium, as part of their plans to redevelop the Olympic Stadium after the 2012 Summer Olympics and Paralympics.[35]

In 2013, a plan to build a replica of the destroyed Crystal Palace was proposed by a Chinese developer.[36][37][38] Bromley Council however cancelled the exclusivity agreement with the developer in 2015.[39]

References

- "Map of Crystal Palace Park". Crystal Palace Park, Penge, South London. Cadillac Owners Club of Great Britain. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Historic England, "Crystal Palace Park (1000373)", National Heritage List for England, retrieved 19 November 2017

- "History of The Crystal Palace (Part 1)". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- "Leaving Hyde Park, 1851". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- "About Crystal Palace Park: History of the park". Bromley Council. Archived from the original on 27 September 2013. Retrieved 28 July 2013.

- Camberwell: Divisions of the New Borough (Map) Ordnance Survey, 1885

- "The Rebuilding at Sydenham, 1852-1854". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- "History of The Crystal Palace (Part 2)". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- "Dinosaur Audio Tour".

- "Making History - The Crystal Palace atmospheric railway". Archived from the original on 12 February 2010.

- "Crystal Palace High Level and Upper Norwood". Disused Stations.

- "Disaster strikes, 1936". The Crystal Palace Foundation.

- Vanessa Thorpe (29 April 2007), "Brunel to tower again over Crystal Palace", The Observer

- "Crystal Palace Aquarium Co Ltd". Crystal Palace Foundation.

- Williams, David (17 May 2013). "Motor to the Palace for action-packed vintage racing". London Evening Standard. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- "Skiers - Edinburgh And Crystal Palace 1967".

- "History". Crystal Palace Park.

- "The Italian Terraces at Crystal Palace". The Victorian Web.

- "Animal statues in London". Time Out. 10 July 2007. Archived from the original on 22 February 2014. Retrieved 17 February 2014.

- "Girlguiding Centenary Maze". Archived from the original on 24 February 2011.

- "Music, Saurians and Colored Fire at the Crystal Palace".

- "Crystal Palace Concert Platform". Ian Ritchie Architects.

- https://www.bromley.gov.uk/press/article/1572/creative_proposals_wanted_for_the_future_of_the_concert_platform

- "RNVR Great War Memorial Bell - Crystal Palace Park, London, UK - Bells on Waymarking.com". Waymarking.com.

- "Information about the Museum". The Crystal Palace Museum. Archived from the original on 17 August 2013. Retrieved 29 July 2013.

- Walk London, Capital Ring, Section 3, Grove Park to Crystal Palace Archived 27 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- "Crystal Palace Park". House of Commons Hansard. Archived from the original on 9 May 2016. Retrieved 23 April 2016.

- "Bromley London Borough Council (Crystal Palace) Bill (By Order)". They Work For You.

- "Background to the Development at Crystal Palace - Campaign History". Crystal Palace Campaign.

- Alison Freeman (7 November 2003). "Glass icon for Crystal Palace". BBC News.

- Cara Lee and Gemma Wheatley (22 October 2007). "£67m Crystal Palace Park masterplan unveiled". Croydon Guardian.

- "Masterplan, environmental statement non-technical summary" (PDF). London Development Agency.

- "High Court upholds £68m Crystal Palace Park redevelopment plans". BBC News. 13 June 2012.

- "Crystal Palace unveil plans for National Sports Centre". BBC Sport - Football. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 29 May 2013.

- Bisby, Sam (28 January 2011). "Tottenham release images of proposed Crystal Palace Athletics Stadium". Goal.com.

- "Plans for Crystal Palace replica". BBC News. 27 July 2013.

- "Crystal Palace Park - what next?". London Borough of Bromley Website. London Borough of Bromley. Archived from the original on 11 October 2013. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- "The Crystal Palace - About the development". The London Crystal Palace Website. ZhongRong Group. Retrieved 15 October 2013.

- Mann, Will. "Shattered:£500M Crystal Palace rebuild plan". New Civil Engineer.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Crystal Palace Park. |

- Crystal Palace Park – map of the park as was until recently

- The Crystal Palace, sources from www.victorianlondon.org