Church architecture

Church architecture refers to the architecture of buildings of Christian churches. It has evolved over the two thousand years of the Christian religion, partly by innovation and partly by imitating other architectural styles as well as responding to changing beliefs, practices and local traditions. From the birth of Christianity to the present, the most significant objects of transformation for Christian architecture and design were the great churches of Byzantium, the Romanesque abbey churches, Gothic cathedrals and Renaissance basilicas with its emphasis on harmony. These large, often ornate and architecturally prestigious buildings were dominant features of the towns and countryside in which they stood. However, far more numerous were the parish churches in Christendom, the focus of Christian devotion in every town and village. While a few are counted as sublime works of architecture to equal the great cathedrals and churches, the majority developed along simpler lines, showing great regional diversity and often demonstrating local vernacular technology and decoration.

Buildings were at first from those originally intended for other purposes but, with the rise of distinctively ecclesiastical architecture, church buildings came to influence secular ones which have often imitated religious architecture. In the 20th century, the use of new materials, such as steel and concrete, has had an effect upon the design of churches. The history of church architecture divides itself into periods, and into countries or regions and by religious affiliation. The matter is complicated by the fact that buildings put up for one purpose may have been re-used for another, that new building techniques may permit changes in style and size, that changes in liturgical practice may result in the alteration of existing buildings and that a building built by one religious group may be used by a successor group with different purposes.

Origins and development of the church building

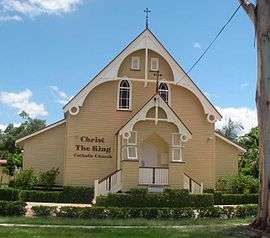

The simplest church building comprises a single meeting space, built of locally available material and using the same skills of construction as the local domestic buildings. Such churches are generally rectangular, but in African countries where circular dwellings are the norm, vernacular churches may be circular as well. A simple church may be built of mud brick, wattle and daub, split logs or rubble. It may be roofed with thatch, shingles, corrugated iron or banana leaves. However, church congregations, from the 4th century onwards, have sought to construct church buildings that were both permanent and aesthetically pleasing. This had led to a tradition in which congregations and local leaders have invested time, money and personal prestige into the building and decoration of churches.

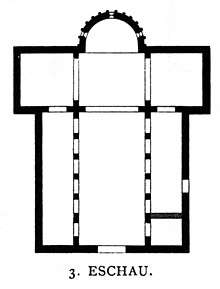

Within any parish, the local church is often the oldest building and is larger than any pre-19th-century structure except perhaps a barn. The church is often built of the most durable material available, often dressed stone or brick. The requirements of liturgy have generally demanded that the church should extend beyond a single meeting room to two main spaces, one for the congregation and one in which the priest performs the rituals of the Mass. To the two-room structure is often added aisles, a tower, chapels, and vestries and sometimes transepts and mortuary chapels. The additional chambers may be part of the original plan, but in the case of a great many old churches, the building has been extended piecemeal, its various parts testifying to its long architectural history.

Beginnings

In the first three centuries of the Early Livia Christian Church, the practice of Christianity was illegal and few churches were constructed. In the beginning, Christians worshipped along with Jews in synagogues and in private houses. After the separation of Jews and Christians, the latter continued to worship in people's houses, known as house churches. These were often the homes of the wealthier members of the faith. Saint Paul, in his first letter to the Corinthians writes: "The churches of Asia send greetings. Aquila and Prisca, together with the church in their house, greet you warmly in the Lord."[1]

Some domestic buildings were adapted to function as churches. One of the earliest of adapted residences is at Dura Europos church, built shortly after 200 AD, where two rooms were made into one, by removing a wall, and a dais was set up. To the right of the entrance a small room was made into a baptistry.

Some church buildings were specifically built as church assemblies, such as that opposite the emperor Diocletian's palace in Nicomedia. Its destruction was recorded thus:

When that day dawned, in the eighth consulship of Diocletian and seventh of Maximian, suddenly, while it was yet hardly light, the perfect, together with chief commanders, tribunes, and officers of the treasury, came to the church in Nicomedia, and the gates having been forced open, they searched everywhere for an idol of the Divinity. The books of the Holy Scriptures were found, and they were committed to the flames; the utensils and furniture of the church were abandoned to pillage: all was rapine, confusion, tumult. That church, situated on rising ground, was within view of the palace; and Diocletian and Galerius stood as if on a watchtower, disputing long whether it ought to be set on fire. The sentiment of Diocletian prevailed, who dreaded lest, so great a fire being once kindled, some part of the city might he burnt; for there were many and large buildings that surrounded the church. Then the Pretorian Guards came in battle array, with axes and other iron instruments, and having been let loose everywhere, they in a few hours leveled that very lofty edifice with the ground.[2]

From house church to church

From the first to the early fourth centuries most Christian communities worshipped in private homes, often secretly. Some Roman churches, such as the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome, are built directly over the houses where early Christians worshipped. Other early Roman churches are built on the sites of Christian martyrdom or at the entrance to catacombs where Christians were buried.

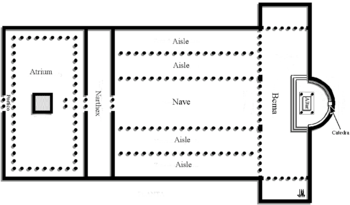

With the victory of the Roman emperor Constantine at the Battle of Milvian Bridge in 312 AD, Christianity became a lawful and then the privileged religion of the Roman Empire. The faith, already spread around the Mediterranean, now expressed itself in buildings. Christian architecture was made to correspond to civic and imperial forms, and so the Basilica, a large rectangular meeting hall became general in east and west, as the model for churches, with a nave and aisles and sometimes galleries and clerestories. While civic basilicas had apses at either end, the Christian basilica usually had a single apse where the bishop and presbyters sat in a dais behind the altar. While pagan basilicas had as their focus a statue of the emperor, Christian basilicas focused on the Eucharist as the symbol of the eternal, loving and forgiving God.

The first very large Christian churches, notably Santa Maria Maggiore, San Giovanni in Laterano, and Santa Costanza, were built in Rome in the early 4th century.[3]

Characteristics of the early Christian church building

The church building as we know it grew out of a number of features of the Ancient Roman period:

Atrium

When Early Christian communities began to build churches they drew on one particular feature of the houses that preceded them, the atrium, or courtyard with a colonnade surrounding it. Most of these atriums have disappeared. A fine example remains at the Basilica of San Clemente in Rome and another was built in the Romanesque period at Sant'Ambrogio, Milan. The descendants of these atria may be seen in the large square cloisters that can be found beside many cathedrals, and in the huge colonnaded squares or piazza at the Basilicas of St Peter's in Rome and St Mark's in Venice and the Camposanto (Holy Field) at the Cathedral of Pisa.

Basilica

Early church architecture did not draw its form from Roman temples, as the latter did not have large internal spaces where worshipping congregations could meet. It was the Roman basilica, used for meetings, markets and courts of law that provided a model for the large Christian church and that gave its name to the Christian basilica.[4]

Both Roman basilicas and Roman bath houses had at their core a large vaulted building with a high roof, braced on either side by a series of lower chambers or a wide arcaded passage. An important feature of the Roman basilica was that at either end it had a projecting exedra, or apse, a semicircular space roofed with a half-dome. This was where the magistrates sat to hold court. It passed into the church architecture of the Roman world and was adapted in different ways as a feature of cathedral architecture.[3]

The earliest large churches, such as the Cathedral of San Giovanni in Laterano in Rome, consisted of a single-ended basilica with one apsidal end and a courtyard, or atrium, at the other end. As Christian liturgy developed, processions became part of the proceedings. The processional door was that which led from the furthest end of the building, while the door most used by the public might be that central to one side of the building, as in a basilica of law. This is the case in many cathedrals and churches.[5]

Bema

As numbers of clergy increased, the small apse which contained the altar, or table upon which the sacramental bread and wine were offered in the rite of Holy Communion, was not sufficient to accommodate them. A raised dais called a bema formed part of many large basilican churches. In the case of St. Peter's Basilica and San Paolo Fuori le Mura (St Paul's outside the Walls) in Rome, this bema extended laterally beyond the main meeting hall, forming two arms so that the building took on the shape of a T with a projecting apse. From this beginning, the plan of the church developed into the so-called Latin Cross which is the shape of most Western Cathedrals and large churches. The arms of the cross are called the transept.[6]

Mausoleum

One of the influences on church architecture was the mausoleum. The mausoleum of a noble Roman was a square or circular domed structure which housed a sarcophagus. The Emperor Constantine built for his daughter Costanza a mausoleum which has a circular central space surrounded by a lower ambulatory or passageway separated by a colonnade. Santa Costanza's burial place became a place of worship as well as a tomb. It is one of the earliest church buildings that was central, rather than longitudinally planned. Constantine was also responsible for the building of the circular, mausoleum-like Church of the Holy Sepulchre in Jerusalem, which in turn influenced the plan of a number of buildings, including that constructed in Rome to house the remains of the proto-martyr Stephen, San Stefano Rotondo and the Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna.

Ancient circular or polygonal churches are comparatively rare. A small number, such as the Temple Church, London were built during the Crusades in imitation of the Church of the Holy Sepulchre as isolated examples in England, France, and Spain. In Denmark such churches in the Romanesque style are much more numerous. In parts of Eastern Europe, there are also round tower-like churches of the Romanesque period but they are generally vernacular architecture and of small scale. Others, like St Martin's Rotunda at Visegrad, in the Czech Republic, are finely detailed.

The circular or polygonal form lent itself to those buildings within church complexes that perform a function in which it is desirable for people to stand, or sit around, with a centralized focus, rather than an axial one. In Italy, the circular or polygonal form was used throughout the medieval period for baptisteries, while in England it was adapted for chapter houses. In France, the aisled polygonal plan was adopted as the eastern terminal and in Spain, the same form is often used as a chapel.

Other than Santa Costanza and San Stefano, there was another significant place of worship in Rome that was also circular, the vast Ancient Roman Pantheon, with its numerous statue-filled niches. This too was to become a Christian church and lend its style to the development of Cathedral architecture.

Latin cross and Greek cross

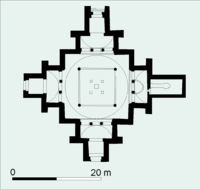

Most cathedrals and great churches have a cruciform groundplan. In churches of Western European tradition, the plan is usually longitudinal, in the form of the so-called Latin Cross, with a long nave crossed by a transept. The transept may be as strongly projecting as at York Minster or not project beyond the aisles as at Amiens Cathedral.

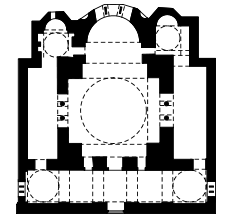

Many of the earliest churches of Byzantium have a longitudinal plan. At Hagia Sophia, Istanbul, there is a central dome, the frame on one axis by two high semi-domes and on the other by low rectangular transept arms, the overall plan being square. This large church was to influence the building of many later churches, even into the 21st century. A square plan in which the nave, chancel and transept arms are of equal length forming a Greek cross, the crossing generally surmounted by a dome became the common form in the Eastern Orthodox Church, with many churches throughout Eastern Europe and Russia being built in this way. Churches of the Greek Cross form often have a narthex or vestibule which stretches across the front of the church. This type of plan was also to later play a part in the development of church architecture in Western Europe, most notably in Bramante's plan for St. Peter's Basilica.[3][6]

Divergence of Eastern and Western church architecture

The division of the Roman Empire in the fourth century AD, resulted in Christian ritual evolving in distinctly different ways in the eastern and western parts of the empire. The final break was the Great Schism of 1054.

Eastern Orthodoxy and Byzantine architecture

Eastern Christianity and Western Christianity began to diverge from each other from an early date. Whereas the basilica was the most common form in the west, a more compact centralized style became predominant in the east. These churches were in origin martyria, constructed as mausoleums housing the tombs of the saints who had died during the persecutions which only fully ended with the conversion of Emperor Constantine. An important surviving example is the Mausoleum of Galla Placidia in Ravenna, which has retained its mosaic decorations. Dating from the 5th century, it may have been briefly used as an oratory before it became a mausoleum.

These buildings copied pagan tombs and were square, cruciform with shallow projecting arms or polygonal. They were roofed by domes which came to symbolize heaven. The projecting arms were sometimes roofed with domes or semi-domes that were lower and abutted the central block of the building. Byzantine churches, although centrally planned around a domed space, generally maintained a definite axis towards the apsidal chancel which generally extended further than the other apses. This projection allowed for the erection of an iconostasis, a screen on which icons are hung and which conceals the altar from the worshippers except at those points in the liturgy when its doors are opened.

The architecture of Constantinople (Istanbul) in the 6th century produced churches that effectively combined centralized and basilica plans, having semi-domes forming the axis, and arcaded galleries on either side. The church of Hagia Sophia (now a museum) was the most significant example and had an enormous influence on both later Christian and Islamic architecture, such as the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem and the Umayyad Great Mosque in Damascus. Many later Eastern Orthodox churches, particularly large ones, combine a centrally planned, domed eastern end with an aisled nave at the west.

A variant form of the centralized church was developed in Russia and came to prominence in the sixteenth century. Here the dome was replaced by a much thinner and taller hipped or conical roof which perhaps originated from the need to prevent snow from remaining on roofs. One of the finest examples of these tented churches is St. Basil's in Red Square in Moscow.

Medieval West

Participation in worship, which gave rise to the porch church, began to decline as the church became increasingly clericalized; with the rise of the monasteries church buildings changed as well. The 'two-room' church' became, in Europe, the norm. The first 'room', the nave, was used by the congregation; the second 'room', the sanctuary, was the preserve of the clergy and was where the Mass was celebrated. This could then only be seen from a distance by the congregation through the arch between the rooms (from late mediaeval times closed by a wooden partition, the Rood screen), and the elevation of the host, the bread of the communion, became the focus of the celebration: it was not at that time generally partaken of by the congregation. Given that the liturgy was said in Latin, the people contented themselves with their own private devotions until this point. Because of the difficulty of sight lines, some churches had holes, 'squints', cut strategically in walls and screens, through which the elevation could be seen from the nave. Again, from the twin principles that every priest must say his mass every day and that an altar could only be used once, in religious communities a number of altars were required for which space had to be found, at least within monastic churches.

Apart from changes in the liturgy, the other major influence on church architecture was in the use of new materials and the development of new techniques. In northern Europe, early churches were often built of wood, for which reason almost none survive. With the wider use of stone by the Benedictine monks, in the tenth and eleventh centuries, larger structures were erected.

The two-room church, particularly if it were an abbey or a cathedral, might acquire transepts. These were effectively arms of the cross which now made up the ground plan of the building. The buildings became more clearly symbolic of what they were intended for. Sometimes this crossing, now the central focus of the church, would be surmounted by its own tower, in addition to the west end towers, or instead of them. (Such precarious structures were known to collapse – as at Ely – and had to be rebuilt.) Sanctuaries, now providing for the singing of the offices by monks or canons, grew longer and became chancels, separated from the nave by a screen. Practical function and symbolism were both at work in the process of development.

Factors affecting the architecture of churches

Across Europe, the process by which church architecture developed and individual churches were designed and built was different in different regions, and sometimes differed from church to church in the same region and within the same historic period.

Among the factors that determined how a church was designed and built are the nature of the local community, the location in city, town or village, whether the church was an abbey church, whether the church was a collegiate church, whether the church had the patronage of a bishop, whether the church had the ongoing patronage of a wealthy family and whether the church contained relics of a saint or other holy objects that were likely to draw pilgrimage.

Collegiate churches and abbey churches, even those serving small religious communities, generally demonstrate a greater complexity of form than parochial churches in the same area and of a similar date.

Churches that have been built under the patronage of a bishop have generally employed a competent church architect and demonstrate in the design refinement of style unlike that of the parochial builder.

Many parochial churches have had the patronage of wealthy local families. The degree to which this has an effect on the architecture can differ greatly. It may entail the design and construction of the entire building having been financed and influenced by a particular patron. On the other hand, the evidence of patronage may be apparent only in accretion of chantry chapels, tombs, memorials, fittings, stained glass, and other decorations.

Churches that contain famous relics or objects of veneration and have thus become pilgrimage churches are often very large and have been elevated to the status of basilica. However, many other churches enshrine the bodies or are associated with the lives of particular saints without having attracted continuing pilgrimage and the financial benefit that it brought.

The popularity of saints, the veneration of their relics, and the size and importance of the church built to honor them are without consistency and can be dependent upon entirely different factors. Two virtually unknown warrior saints, San Giovanni and San Paolo, are honoured by one of the largest churches in Venice, built by the Dominican Friars in competition to the Franciscans who were building the Frari Church at the same time. The much smaller church that contained the body of Saint Lucy, a martyr venerated by Catholics and Protestants across the world and the titular saint of numerous locations, was demolished in the late 19th century to make way for Venice's railway station.

The first truly baroque façade was built in Rome between 1568 and 1584 for the Church of the Gesù, the mother church of the Society of Jesus (Jesuits). It introduced the baroque style into architecture. Corresponding with the Society's theological task as the spearhead of the Counter-Reformation, the new style soon became a triumphant feature in Catholic church architecture.

After the second world war, modern materials and techniques such as concrete and metal panels were introduced in Norwegian church construction. Bodø Cathedral for instance was built in reinforced concrete allowing a wide basilica to be built. During the 1960s there was a more pronounced break from tradition as in the Arctic Cathedral built in lightweight concrete and covered in aluminum sidings.

Wooden churches

In Norway, church architecture has been affected by wood as the preferred material, particularly in sparsely populated areas. Churches built until the second world war are about 90% wooden except medieval constructions.[7] During the Middle Ages all wooden churches in Norway (about 1000 in total) were constructed in the stave church technique, but only 271 masonry constructions.[8] After the Protestant reformation when the construction of new (or replacement of old) churches was resumed, wood was still the dominant material but the log technique became dominant.[9] The log construction gave a lower more sturdy style of building compared to the light and often tall stave churches. Log construction became structurally unstable for long and tall walls, particularly if cut through by tall windows. Adding transepts improved the stability of the log technique and is one reason why the cruciform floor plan was widely used during 1600 and 1700s. For instance the Old Olden Church (1759) replaced a building damaged by hurricane, the 1759 church was then constructed in cruciform shape to make it withstand the strongest winds.[10] The length of trees (logs) also determined the length of walls according to Sæther.[11] In Samnanger church for instance, outside corners have been cut to avoid splicing logs, the result is an octagonal floor plan rather than rectangular.[12] The cruciform constructions provided a more rigid structure and larger churches, but view to the pulpit and altar was obstructed by interior corners for seats in the transept. The octagonal floor plan offers good visibility as well as a rigid structure allowing a relatively wide nave to be constructed - Håkon Christie believes that this is a reason why the octagonal church design became popular during the 1700s.[9] Vreim believes that the introduction of log technique after the reformation resulted in a multitude of church designs in Norway.[13]

In Ukraine, wood church constructions originate from the introduction of Christianity and continued to be widespread, particularly in rural areas, when masonry churches dominated in cities and in Western Europe.

Regional church architecture

Church architecture varies depending on both the sect of the faith, as well as the geographical location and the influences acting upon it. Variances from the typical church architecture as well as unique characteristics can be seen in many areas around the globe.

American church architecture

The split between Eastern and Western Church Architecture extended its influence into the churches we see in America today as well. America's churches are an amalgamation of the many styles and cultures that collided here, examples being St. Constantine, a Ukrainian Greek Catholic Church in Minneapolis, Polish Cathedral style churches, and Russian Orthodox churches, found all across the country.[14] There are remnants of the Byzantine inspired architecture in many of the churches, such as the large domed ceilings, extensive stonework, and a maximizing of space to be used for religious iconography on walls and such.[14] Churches classified as Ukrainian or Catholic also seem to follow the trend of being overall much more elaborately decorated and accentuated than their Protestant counterparts, in which decoration is simple.[14]

Specifically in Texas, there are remnants of the Anglo-American colonization that are visible in the architecture itself.[15] Texas in itself was a religious hotbed, and so ecclesiastical architecture developed at a faster pace than in other areas. Looking at the Antebellum period, (1835–1861) Church architecture shows the values and personal beliefs of the architects who created them, while also showcasing Texan cultural history.[15] Both the Catholic and Protestant buildings showed things such as the architectural traditions, economic circumstances, religious ordinances, and aesthetic tastes[15] of those involved. The movement to keep ethnicities segregated during this time was also present in the very foundations of this architecture. Their physical appearances vary wildly from area to area though, as each served its own local purpose, and as mentioned before, due to the multitude of religious groups, each held a different set of beliefs.[15]

English church architecture

The history of England's churches is extensive, their style has gone through many changes and has had numerous influences such as 'geographical, geological, climatic, religious, social and historical, shape it.[16] One of the earliest style changes is shown in the Abbey Church of Westminster, which was built in a foreign style and was a cause for concern for many as it heralded change.[16] A second example is St Paul's Cathedral, which was one of the earliest Protestant Cathedrals in England. There are many other notable churches that have each had their own influence on the ever-changing style in England, such as Truro, Westminster Cathedral, Liverpool and Guildford.[16] Between the thirteenth and fourteenth centuries, the style of church architecture could be called 'Early English' and 'Decorated'. This time is considered to be when England was in its prime in the category of a church building. It was after the Black Death that the style went through another change, the 'perpendicular style', where ornamentation became more extravagant.[16]

An architectural element that appeared soon after the Black Death style change and is observed extensively in Medieval English styles is fan vaulting, seen in the Chapel of Henry VII and the King's College Chapel in Cambridge.[16] After this, the prevalent style was Gothic for around 300 years but the style was clearly present for many years before that as well. In these late Gothic times, there was a specific way in which the foundations for the churches were built. First, a stone skeleton would be built, then the spaces between the vertical supports filled with large glass windows, then those windows supported by their own transoms and mullions.[16] On the topic of church windows, the windows are somewhat controversial as some argue that the church should be flooded with light and some argue that they should be dim for an ideal praying environment.[16] Most church plans in England have their roots in one of two styles, Basilican and Celtic and then we see the later emergence of a 'two-cell' plan, consisting of nave and sanctuary.[16]

In the time before the last war, there was a movement towards a new style of architecture, one that was more functional than embellished.[16] There was an increased use of steel and concrete and a rebellion against the romantic nature of the traditional style. This resulted in a 'battle of the styles'[16] in which one side was leaning towards the modernist, functional way of design, and the other was following traditional Romanesque, Gothic, and Renaissance styles,[16] as reflected in the architecture of all buildings, not just churches.

Wallachian church architecture

In the early Romanian territory of Wallachia, there were three major influences that can be seen. The first are the western influences of Gothic and Romanesque styles,[17] before later falling to the greater influence of the Byzantine styles. The early western influences can be seen in two places, the first is a church in Câmpulung, that showcases distinctly Romanesque styles, and the second are the remnants of a church in Drobeta-Turnu Severin, which has features of the Gothic style.[17] There are not many remaining examples of those two styles, but the Byzantine influence is much more prominent. A few prime examples of the direct Byzantine influence are the St. Nicoara and Domneasca in Curtea de Arges, and church at Nicopolis in Bulgaria. These all show the characteristic features such as sanctuaries, rectangular naves, circular interiors with non-circular exteriors, and small chapels.[17] The Nicopolis church and the Domneasca both have Greek-inspired plans, but the Domneasca is far more developed than the Nicopolis church. Alongside these are also traces of Serbian, Georgian, and Armenian influences that found their way to Wallachia through Serbia.[17]

Taiwanese church architecture

In East Asia, Taiwan is one of several countries famous for its church architecture. The Spanish Fort San Domingo in the 17th century had an adjacent church. The Dutch Fort Zeelandia in Tainan also included a chapel. In modern architecture several churches have been inspired to use traditional designs. These include the Church of the Good Shepherd in Shihlin (Taipei), which was designed by Su Hsi Tsung and built in the traditional siheyuan style. The chapel of Taiwan Theological College and Seminary includes a pagoda shape and traditional tile-style roof. Zhongshan and Jinan Presbyterian churches were built during the Japanese era (1895-1945) and reflect a Japanese aesthetic.[18] Tunghai University's Luce Memorial Chapel, designed by IM Pei's firm, is often held up as an example of a modern, contextualized style.

Gothic era church architecture

Gothic-era architecture, originating in 12th-century France, is a style where curves, arches, and complex geometry are highly emphasized. These intricate structures, often of immense size, required great amounts of planning, effort and resources; involved large numbers of engineers and laborers; and often took hundreds of years to complete—all of which was considered a tribute to God.

Characteristics

The characteristics of a Gothic-style church are largely in congruence with the ideology that the more breathtaking a church is, the better it reflects the majesty of God. This was accomplished through clever math and engineering in a time period where complex shapes, especially in huge cathedrals, were not typically found in structures. Through this newly implemented skill of being able to design complex shapes churches consisted of namely pointed arches, curved lights and windows, and rib vaults.[19][20] Since these newly popular designs were implemented with respect to the width of the church rather than height, width was much more desired rather than height.[21]

Art

Gothic architecture in churches had a heavy emphasis on art. Just like the structure of the building, there was an emphasis on complex geometric shapes. An example of this is stained glass windows, which can still be found in modern churches. Stained glass windows were both artistic and functional in the way that they allowed colored light to enter the church and create a heavenly atmosphere.[22] Other popular art styles in the Gothic era were sculptures. Creating lifelike depictions of figures, again with the use of complex curves and shapes. Artists would include a high level of detail to best preserve and represent their subject.[23]

Time periods and styles

The Gothic era, first referred to by historiographer Giorgio Vasari,[19] began in northeastern France and slowly spread throughout Europe. It was perhaps most characteristically expressed in the Rayonnant style, originating in the 13th century, known for its exaggerated geometrical features that made everything as astounding and eye-catching as possible. Gothic churches were often highly decorated, with geometrical features applied to already complex structural forms.[21] By the time the Gothic period neared its close, its influence had spread to residences, guild halls, and public and government buildings.

Notable examples

- Chartres Cathedral

- Santa Maria del Fiore

- Cologne Cathedral

- Notre Dame de Paris

- Monastery of Batalha

Ethiopian-Eritrean church architecture

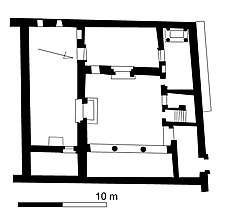

Although having its roots in the traditions of Eastern Christianity – especially the Syrian church – as well as later being exposed to European influences – the traditional architectural style of Orthodox Tewahedo (Ethiopian Orthodox-Eritrean Orthodox) churches has followed a path all its own. The earliest known churches show the familiar basilican layout. For example, the church of Debre Damo is organized around a nave of four bays separated by re-used monolithic columns; at the western end is a low-roofed narthex, while on the eastern is the maqdas, or Holy of Holies, separated by the only arch in the building.[24]

The next period, beginning in the second half of the first millennium AD and lasting into the 16th century, includes both structures built of conventional materials, and those hewn from rock. Although most surviving examples of the first are now found in caves, Thomas Pakenham discovered an example in Wollo, protected inside the circular walls of later construction.[25] An example of these built-up churches would be the church of Yemrehana Krestos, which has many resemblances to the church of Debre Damo both in plan and construction.[26]

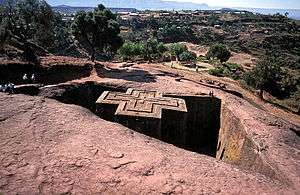

The other style of this period, perhaps the most famous architectural tradition of Ethiopia, are the numerous monolithic churches. This includes houses of worship carved out of the side of mountains, such as Abreha we Atsbeha, which although approximately square the nave and transepts combine to form a cruciform outline – leading experts to categorize Abreha we Atsbeha as an example of cross-in-square churches. Then there are the churches of Lalibela, which were created by excavating into "a hillside of soft, reddish tuff, variable in hardness and composition". Some of the churches, such as Bete Ammanuel and the cross-shaped Bete Giyorgis, are entirely free-standing with the volcanic tuff removed from all sides, while other churches, such as Bete Gabriel-Rufael and Bete Abba Libanos, are only detached from the living rock on one or two sides. All of the churches are accessed through a labyrinth of tunnels.[27]

The final period of Ethiopian church architecture, which extends to the present day, is characterized by round churches with conical roofs – quite similar to the ordinary houses the inhabitants of the Ethiopian highlands live in. Despite this resemblance, the interiors are quite different in how their rooms are laid out, based on a three-part division of:

The Reformation and its influence on church architecture

In the early 16th century, the Reformation brought a period of radical change to church design. On Christmas Day 1521, Andreas Karlstadt performed the first reformed communion service. In early January 1522, the Wittenberg city council authorized the removal of imagery from churches and affirmed the changes introduced by Karlstadt on Christmas. According to the ideals of the Protestant Reformation, the spoken word, the sermon, should be central act in the church service. This implied that the pulpit became the focal point of the church interior and that churches should be designed to allow all to hear and see the minister.[29] Pulpits had always been a feature of Western churches. The birth of Protestantism led to extensive changes in the way that Christianity was practiced (and hence the design of churches).

During the Reformation period, there was an emphasis on "full and active participation". The focus of Protestant churches was on the preaching of the Word, rather than a sacerdotal emphasis. Holy Communion tables became wood to emphasise that Christ's sacrifice was made once for all and were made more immediate to the congregation to emphasise man's direct access to God through Christ. Therefore, catholic churches were redecorated when they became reformed: Paintings and statues of saints were removed and sometimes the altar table was placed in front of the pulpit, as in Strasbourg Cathedral in 1524. The pews were turned towards the pulpit. Wooden galleries were built to allow more worshippers to follow the sermon.

The first newly built Protestant church was the court chapel of Neuburg Castle in 1543, followed by the court chapel of Hartenfels Castle in Torgau, consecrated by Martin Luther on 5 October 1544.

Images and statues were sometimes removed in disorderly attacks and unofficial mob actions (in the Netherlands called the Beeldenstorm). Medieval churches were stripped of their decorations, such as the Grossmünster in Zürich in 1524, a stance enhanced by the Calvinist reformation, beginning with its main church, St. Pierre Cathedral in Geneva, in 1535. At the Peace of Augsburg of 1555, which ended a period of armed conflict between Roman Catholic and Protestant forces within the Holy Roman Empire, the rulers of the German-speaking states and Charles V, the Habsburg Emperor, agreed to accept the principle Cuius regio, eius religio, meaning that the religion of the ruler was to dictate the religion of those ruled.

In the Netherlands the Reformed church in Willemstad, North Brabant was built in 1607 as the first Protestant church building in the Netherlands, a domed church with an octagonal shape, according to Calvinism's focus on the sermon.[30] The Westerkerk of Amsterdam was built between 1620 and 1631 in Renaissance style and remains the largest church in the Netherlands that was built for Protestants.

By the beginning of the 17th century, in spite of the cuius regio principle, the majority of the peoples in the Habsburg Monarchy had become Protestant, sparking the Counter-Reformation by the Habsburg emperors which resulted in the Thirty Years' War in 1618. In the Peace of Westphalia treaties of 1648 which ended the war, the Habsburgs were obliged to tolerate three Protestant churches in their province of Silesia, where the counter-reformation had not been completely successful, as in Austria, Bohemia and Hungary, and about half of the population still remained Protestant. However, the government ordered these three churches to be located outside the towns, not to be recognisable as churches, they had to be wooden structures, to look like barns or residential houses, and they were not allowed to have towers or bells. The construction had to be accomplished within a year. Accordingly, the Protestants built their three Churches of Peace, huge enough to give space for more than 5,000 people each. When Protestant troops under Swedish leadership again threatened to invade the Habsburg territories during the Great Northern War, the Habsburgs were forced to allow more Protestant churches within their empire with the Treaty of Altranstädt (1707), however limiting these with similar requirements, the so-called Gnadenkirchen (Churches of Grace). They were mostly smaller wooden structures.

In Britain during the seventeenth and eighteenth centuries, it became usual for Anglican churches to display the Royal Arms inside, either as a painting or as a relief, to symbolise the monarch's role as head of the church.[31]

During the 17th and 18th centuries Protestant churches were built in the baroque style that originated in Italy, however consciously more simply decorated. Some could still become fairly grand, for instance the Katarina Church, Stockholm, St. Michael's Church, Hamburg or the Dresden Frauenkirche, built between 1726 and 1743 as a sign of the will of the citizen to remain Protestant after their ruler had converted to Catholicism.

Some churches were built with a new and genuinely Protestant alignment: the transept became the main church while the nave was omitted, for instance at the Ludwigskirche in Saarbrücken; this building scheme was also quite popular in Switzerland, with the largest being the churches of Wädenswil (1767) and Horgen (1782). A new Protestant interior design scheme was established in many German Lutheran churches during the 18th century, following the example of the court chapel of Wilhelmsburg Castle of 1590: The connection of altar with baptismal font, pulpit and organ in a vertical axis. The central painting above the altar was replaced with the pulpit.

Neo-Lutheranism in the early 19th century criticized this scheme as being too profane. The German Evangelical Church Conference therefore recommended the Gothic language of forms for church building in 1861. Gothic Revival architecture began its triumphal march. With regard to Protestant churches it was not only an expression of historism, but also of a new theological programme which put the Lord's supper above the sermon again. Two decades later liberal Lutherans and Calvinists expressed their wish for a new genuinely Protestant church architecture, conceived on the basis of liturgical requirements. The spaces for altar and worshippers should no longer be separated from each other. Accordingly, churches should not only give space for service, but also for social activities of the parish. Churches were to be seen as meeting houses for the celebrating faithful. The Ringkirche in Wiesbaden was the first church realised according to this ideology in 1892–94. The unity of the parish was expressed by an architecture that united the pulpit and the altar in its circle, following early Calvinist tradition.

Modernism

The idea that worship was a corporate activity and that the congregation should be in no way excluded from sight or participation derives from the Liturgical Movement. Simple one-room plans are almost of the essence of modernity in architecture. In France and Germany between the first and second World Wars, some of the major developments took place. The church at Le Raincy near Paris by Auguste Perret is cited as the starting point of process, not only for its plan but also for the materials used, reinforced concrete. More central to the development of the process was Schloss Rothenfels-am-Main in Germany which was remodelled in 1928. Rudolf Schwartz, its architect, was hugely influential on later church building, not only on the continent of Europe but also in the United States of America. Schloss Rothenfels was a large rectangular space, with solid white walls, deep windows and a stone pavement. It had no decoration. The only furniture consisted of a hundred little black cuboid moveable stools. For worship, an altar was set up and the faithful surrounded it on three sides.

Corpus Christi in Aachen was Schwartz's first parish church and adheres to the same principles, very much reminiscent of the Bauhaus movement of art. Externally it is a plan cube; the interior has white walls and colourless windows, a langbau i.e. a narrow rectangle at the end of which is the altar. It was to be, said Schwartz not 'christocentric' but 'theocentric'. In front of the altar were simple benches. Behind the altar was a great white void of a back wall, signifying the region of the invisible Father. The influence of this simplicity spread to Switzerland with such architects as Fritz Metzger and Dominikus Böhm.

After the Second World War, Metzger continued to develop his ideas, notably with the church of St. Franscus at Basel-Richen. Another notable building is Notre Dame du Haut at Ronchamp by Le Corbusier (1954). Similar principles of simplicity and continuity of style throughout can be found in the United States, in particular at the Roman Catholic Abbey church of St. Procopius, in Lisle, near Chicago (1971).

A theological principle which resulted in change was the decree Sacrosanctum Concilium of the Second Vatican Council issued in December 1963. This encouraged 'active participation' (in Latin: participatio actuosa) by the faithful in the celebration of the liturgy by the people and required that new churches should be built with this in mind (para 124) Subsequently, rubrics and instructions encouraged the use of a freestanding altar allowing the priest to face the people. The effect of these changes can be seen in such churches as the Roman Catholic Metropolitan Cathedrals of Liverpool and the Brasília, both circular buildings with a free-standing altar.

Different principles and practical pressures produced other changes. Parish churches were inevitably built more modestly. Often shortage of finances, as well as a 'market place' theology suggested the building of multi-purpose churches, in which secular and sacred events might take place in the same space at different times. Again, the emphasis on the unity of the liturgical action, was countered by a return to the idea of movement. Three spaces, one for the baptism, one for the liturgy of the word and one for the celebration of the Eucharist with a congregation standing around an altar, were promoted by Richard Giles in England and the United States. The congregation were to process from one place to another. Such arrangements were less appropriate for large congregations than for small; for the former, proscenium arch arrangements with huge amphitheatres such as at Willow Creek Community Church in Chicago in the United States have been one answer.

Postmodernism

As with other Postmodern movements, the Postmodern movement in architecture formed in reaction to the ideals of modernism as a response to the perceived blandness, hostility, and utopianism of the Modern movement. While rare in designs of church architecture, there are nonetheless some notable for recover and renew historical styles and "cultural memory" of Christian architecture. Notable practitioners include Dr. Steven Schloeder, Duncan Stroik, and Thomas Gordon Smith.

The functional and formalized shapes and spaces of the modernist movement are replaced by unapologetically diverse aesthetics: styles collide, form is adopted for its own sake, and new ways of viewing familiar styles and space abound. Perhaps most obviously, architects rediscovered the expressive and symbolic value of architectural elements and forms that had evolved through centuries of building—often maintaining meaning in literature, poetry and art—but which had been abandoned by the modern movement. Church buildings in Nigeria evolved from its foreign monument look of old to the contemporary design which makes it look like a factory.[32]

Images of church architecture from different centuries

Santa María, Cambre, Galicia, Spain

Santa María, Cambre, Galicia, Spain San Pedro de Dozón, Spain

San Pedro de Dozón, Spain- Original building of Roswell Presbyterian Church, Roswell, Georgia, USA

- Margarita, Cuneo, Italy

St Gregory the Great, Kirknewton, Scotland

St Gregory the Great, Kirknewton, Scotland Etchmiadzin Cathedral (483AD), Armenia

Etchmiadzin Cathedral (483AD), Armenia

Front facade of Basilica of Saint Sofia, Sofia

Front facade of Basilica of Saint Sofia, Sofia- Wooroolin Church, Queensland, Australia

Collegiate Church of St Vitus

Collegiate Church of St Vitus Interior view of the Boyana Church, Sofia

Interior view of the Boyana Church, Sofia San Bartolo, San Gimignano

San Bartolo, San Gimignano Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Sofia, Bulgaria

Alexander Nevsky Cathedral, Sofia, Bulgaria

Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano, Tuscany

Sant'Agostino, San Gimignano, Tuscany

Resiutta, Italy

Resiutta, Italy Queensland Carpenter Gothic

Queensland Carpenter Gothic Road church in Baden-Baden, Germany

Road church in Baden-Baden, Germany St Martin's in the Fields, London

St Martin's in the Fields, London- Presbyterian church, Washington, Georgia, 1826

- Katowice, Poland

Alexander Nevsky church in Potsdam, the oldest example of Russian Revival architecture

Alexander Nevsky church in Potsdam, the oldest example of Russian Revival architecture

Rococo choir of Church of Saint-Sulpice, Fougères, Brittany, 16th – 18th century

Rococo choir of Church of Saint-Sulpice, Fougères, Brittany, 16th – 18th century-Nef.jpg) Saint John the Baptist of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, France

Saint John the Baptist of Saint-Jean-de-Luz, France Romanesque interior, Schöngrabern, Austria

Romanesque interior, Schöngrabern, Austria St Bartholomew-the-Great, London

St Bartholomew-the-Great, London Katowice, Poland

Katowice, Poland.jpg) Interior of a Medieval Welsh church c.1910

Interior of a Medieval Welsh church c.1910 St. Andrew Memorial Church in South Bound Brook, New Jersey

St. Andrew Memorial Church in South Bound Brook, New Jersey.jpg) High Altar, Gothic Revival Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania) (1894)

High Altar, Gothic Revival Church of the Good Shepherd (Rosemont, Pennsylvania) (1894)

See also

- Akron plan

- Bell-gable

- Cathedral architecture

- Gothic cathedrals and churches

- Marian and Holy Trinity columns

- Mathematics and architecture

- Monastery

- Oldest churches in the world

- Polish Cathedral style churches in North America

- Religious architecture

- Protestantism in Germany

- Tin tabernacle

- Category:Church architecture

References

Notes

- 1 Corinthians 16:19

- Lactantius. . In Roberts, Alexander; Donaldson, James (eds.). . Ante-Nicene Fathers. 7. Translated by William Fletcher – via Wikisource.

- Grabar, Andre. The Beginnings of Christian Art.

- Ward-Perkins, J.B. (1994). Studies in Roman and Early Christian Architecture. London: The Pindar Press. pp. 455–456.

- Beny; Gunn. Churches of Rome.

- Fletcher, Banister. A History of Architecture

- Muri, Sigurd (1975). Gamle kyrkjer i ny tid (in Norwegian). Oslo: Samlaget.

- Dietrichson, Lorentz (1892). De norske stavkirker. Studier over deres system, oprindelse og historiske udvikling (in Norwegian). Kristiania: Cammermeyer. p. 35.

- Christie, Håkon (1991). "Kirkebygging i Norge i 1600- og 1700-årene". Årbok for Fortidsminneforeningen (in Norwegian). 145: 177–194.

- "County archives about Olden Church". 2000. Archived from the original on 2 October 2013. Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Sæther, Arne E. (1990). Kirken som bygg og bilde. Rom og liturgi mot et tusenårsskifte (in Norwegian). Kirkerådet og Kirkekonsulenten.

- Lidén, Hans-Emil. "Samnanger kirke". Norges Kirker (Churches in Norway) (in Norwegian). Retrieved 14 September 2013.

- Vreim, Halvor (1947). Norsk trearkitektur (in Norwegian). Oslo: Gyldendal.

- Wolniewicz, Richard (1997). "Comparative Ethnic Church Architecture". Polish American Studies. 54 (1): 53–73. JSTOR 20148505.

- Robinson, Willard B. (1990). "Early Anglo-American Church Architecture in Texas". The Southwestern Historical Quarterly. 94 (2): 261–298. JSTOR 30241362.

- Knapp-Fisher, A. B. (1955). "English Church Architecture". Journal of the Royal Society of Arts. 103 (4960): 747–762. JSTOR 41364749.

- Munzer, Zdenka (1944). "Medieval Church Architecture in Walachia". Journal of the American Society of Architectural Historians. 4 (3/4): 24–35. doi:10.2307/901174. JSTOR 901174.

- "Religious Centers," Taipei City Government, https://english.gov.taipei/News_Content.aspx?n=7873143196DAD423&sms=EEF89509F382601F&s=101333D848BD0EBC accessed 2/10/2020

- "Gothic Art – Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- A companion to medieval art: Romanesque and Gothic in Northern Europe. Rudolph, Conrad, 1951-. Malden, MA: Blackwell. 2006. ISBN 978-1405102865. OCLC 62322358.CS1 maint: others (link)

- "Gothic art". Encyclopedia Britannica. Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- "Gothic Art - Medieval Studies - Oxford Bibliographies - obo". Retrieved 26 July 2018.

- Sawon, Hong; Moore, Richard (2016). Guidebook Select French Gothic Cathedrals and Churches. Bloomington, IN: Authorhouse. ISBN 978-1524644314. OCLC 980684353.

- Buxton, David (1970). The Abyssinians. New York: Praeger. pp. 97–99.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pakenham, Thomas (1959). The Mountains of Rasselas. London: Reynal and Co. pp. 124–137.

- Phillipson, David W. (2009). Ancient Churches of Ethiopia. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 75ff.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Phillipson 2009, pp. 123–181

- Buxton 1970, pp. 116–118

- Hosar, Kåre (1988). Sør-Fron kirke. Lokal bakgrunn og impulser utenfra (Dissertation, Art History) (in Norwegian). University of Oslo.

- Kleinbauer, W. Eugene (1988). Modern perspectives in Western art history. An anthology of twentieth-century writings on the visual arts. Toronto: University of Toronto Press & Medieval Academy of America. p. 318.

- "Royal Arms can be seen in churches throughout England but why are they there?". Intriguing History. 30 May 2013. Retrieved 19 November 2015.

- "Architecture". Litcaf. 10 February 2016. Retrieved 4 June 2017.

Bibliography

- Bühren, Ralf van (2008). Kunst und Kirche im 20. Jahrhundert. Die Rezeption des Zweiten Vatikanischen Konzils (in German). Paderborn: Ferdinand Schöningh. ISBN 978-3-506-76388-4.

- Bony, J. (1979). The English Decorated Style. Oxford: Phaidon.

- Davies, J.G. (1971). Dictionary of Liturgy and Worship. London: SCM.

- Giles, Richard (1996). Repitching the Tent. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

- Giles, Richard (2004). Uncommon Worship. Norwich: Canterbury Press.

- Graham-Dixon, Andrew (1996). "Chapter 1". A History of British Art. London: BBC Books.

- Harvey, John (1972). The Mediaeval Architect. London: Wayland.

- Howard, F.E. (1937). The mediaeval styles of the English Parish Church. London: Batsford.

- Menachery, George (ed.) The St. Thomas Christian Encyclopaedia of India, 3 volumes: Trichur 1973, Trichur 1982, Ollur 2009; hundreds of photographs on Indian church architecture.

- Menachery, George, ed. (1998). The Nazranies. Indian Church History Classics. 1. SARAS, Ollur. 500 Photos.

- Pevsner, Nikolaus (1951–1974). The Buildings of England (series), Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Sovik, Edward A. (1973). Architecture for Worship. Minneapolis, Minnesota: Augsburg Publishing House. ISBN 978-0-8066-1320-8. Focusing on modern church architecture, mid-20th-century.

- Schloeder, Steven J. (1998). Architecture in Communion. San Francisco: Ignatius Press.

- "Ecclesiastical Architecture". Catholic Encyclopedia. Retrieved 18 February 2007.

External links

- Oldest Christian chapel in the Holy Land found

- EnVisionChurch.org, Commentaries and case studies on modern church building and architecture

- Photographs of European cathedrals, monasteries and cloisters

- Digital collection with floor plans, details, sections, and elevations of three Buffalo churches from the University at Buffalo Libraries