Cabarzia

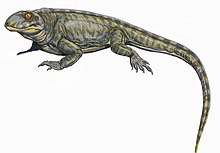

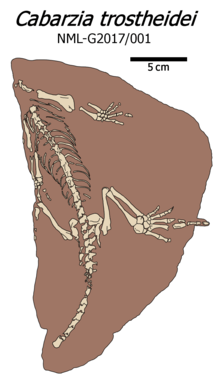

Cabarzia is an extinct genus of varanopid from the Early Permian of Germany. It contains only a single species, Cabarzia trostheidei, which is based on a well-preserved skeleton found in red beds of the Goldlauter Formation. Cabarzia shared many similarities with Mesenosaurus romeri (a varanopid from Russia), although it did retain some differences, such as more curved claws, a wide ulnare, and muscle scars on its sacral ribs. With long, slender hindlimbs, a narrow body, an elongated tail, and short, thick forelimbs, Cabarzia was likely capable of running bipedally to escape from predators, a behavior shared by some modern lizards. It is the oldest animal known to have adaptations for bipedal locomotion, predating Eudibamus, a bipedal bolosaurid parareptile from the slightly younger Tambach Formation.[1]

| Cabarzia | |

|---|---|

| |

| Illustration of the holotype fossil | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Family: | †Varanopidae |

| Subfamily: | †Mycterosaurinae |

| Genus: | †Cabarzia Spindler, Werneberg, & Schneider, 2019 |

| Type species | |

| † Cabarzia trostheidei Spindler, Werneberg, & Schneider, 2019 | |

Discovery

Cabarzia is known from a single articulated skeleton, missing only the head, neck, and portions of the shoulder, tail, and left limbs. This holotype specimen, NML-G2017/001, was discovered in 1989 by Frank Trostheide, a fossil collector prospecting at the Cabarz Quarry in the Thuringian Forest of Germany. This quarry preserves a large portion of the Goldlauter Formation, which is a sequence of Early Permian red beds, lake sediments, and volcanic layers slightly older than the nearby Artinskian or Kungurian-age red beds of the Tambach Formation.[1]

Preliminary study of the specimen tentatively considered it an araeoscelidian diapsid reptile, but a 2019 study by Frederik Spindler, Ralf Werneburg, and Jörg W. Schneider reasoned against that assignment after comparing the postcranial anatomy of small Permian amniotes such as basal synapsids, parareptiles, and eureptiles. They argued that it was likely a varanopid closely related to Mesenosaurus, part of the subfamily Mesenosaurinae which they had named the previous year. The specimen was assigned the name Cabarzia trostheidei in honor of both the locale of its collection and its collector.[1]

Description

The dorsal vertebrae have long centra and widely spaced zygapophyses, giving them an hourglass shape when seen from above. Their neural spines are low, rectangular and blade-like. Cabarzia's vertebrae were relatively simple by varanopid standards, with no distinct lateral excavations or mammillary processes. Mesenosaurus also lacks these characteristics. The seemingly holocephalous (single-headed) ribs, which were already short to begin with, diminished further towards the hip. There were likely only two sacral vertebrae, based on the number of sacral ribs. All of the sacral ribs apparently flared out to the same extent as they contacted the pelvis, like Mesenosaurus, although Cabarzia additionally possessed knob-like scars on the upper surface of its sacral ribs. The caudal (tail) vertebrae were fairly elongated, with thick, hook-shaped caudal ribs proportionally similar to those of Apsisaurus. Preserved portions of the shoulder girdle indicate that Cabarzia had a thin scapula with a convex front edge. The pelvis included an ilium with a long and low dorsal blade and a pubis with a small tubercule.[1]

The forelimb is short and robust relative to the long and slender hindlimb. The humerus in particular is thick, with a large entepicondyle. Cabarzia's entepicondylar foramen was located near the elbow, a far position only otherwise seen in Mesenosaurus among basal synapsids. The radius was relatively short (only slightly longer than the humerus) and was straight, unlike the twisted radius of Mesenosaurus. Most of Cabarzia's carpals (wrist bones) were proportionally similar to those of Mesenosaurus, with a broad intermedium and fairly large proximal carpals and centrale/centralia. However, it also differs due to its characteristically wide ulnare and the retention of two centralia. A tiny pisiform bone is also preserved, much smaller than that of varanodontines. On the other hand, the relative metacarpal proportions of Cabarzia are close to varanodontines.[1]

The femur is neither particularly robust nor slender, but it does have a thin and angular internal trochanter. Like other varanopids (and diapsids), the tibia and fibula were each relatively long, more than 80% the length of the femur. The ratio of the tibia to the longest toe in the foot (the fourth toe) is 3:4, like Mesenosaurus. The astragalus was large and simple, and the calcaneum abutted it along a slightly concave edge surrounding a narrow hole. The fourth distal tarsal is large and unfused to the fifth distal tarsal. As in Mesenosaurus, the elongated fourth metatarsal had a proximal projection which contacted the short fifth metatarsal. The position of the fossil suggests Cabarzia had a fifth toe which was angled relative to the rest of the foot. One of the most clear differences between Cabarzia and Mesenosaurus was the fact that Mesenosaurus had long but rather straight unguals while those of Cabarzia were shorter, deeper, and sharply curved, a characteristic also known in the hands of Tambacarnifex.[1]

Paleobiology

Fused neural spines and well-ossified joints indicate that the holotype specimen of Cabarzia was an adult animal. The curved claws of Cabarzia and Tambacarnifex were likely adapted for predation, in contrast to the more straight claws of Mesenosaurus and Varanops which may have been more useful for digging. The broad ulnare is an adaptation also seen in aquatic animals, although there is no other evidence for aquatic habits in Cabarzia.[1]

Cabarzia's proportions (short forelimbs, thin body, long hindlimbs and tail) are similar to those of modern lizards capable of bipedalism. They also match the Tambach bolosaurid Eudibamus, although the 'sprawling" ankle and foot of Cabarzia are not as specialized for bipedal habits. This may indicate that Cabarzia did not engage in active bipedalism (slow, methodical walking on the hindlimbs) but rather passive bipedalism (a shift into a bipedal posture when running at high speeds, due to the center of weight being behind the hindlimbs). The advantage of passive bipedalism is not fully understood, even in living reptiles, though it may be involved with increased coordination or assistance in the capture of flying insects. Other "mesenosaurines" (such as Mesenosaurus) shared Cabarzia's adaptations for bipedalism, and may have had increased hip musculature to habituate to the lifestyle further. Information on "mesenosaurine" foot proportions afforded by the description of Cabarzia indicates that they are good candidates for the trackmakers of Dromopus, a common Permian reptile footprint ichnogenus which has traditionally been assumed to have been created by araeoscelidian diapsids. Although no known Dromopus fossils seem to correspond to bipedal animals, this is likely due to bipedalism in "mesenosaurines" being restricted to rare circumstances where they are forced to escape predators. As Cabarzia is the oldest known "mesenosaurine" and predates the previously oldest known bipedal animal (Eudibamus) in Thuringian stratigraphy, Cabarzia can be considered the oldest animal known to have practiced bipedalism.[1]

References

- Spindler, Frederik; Werneburg, Ralf; Schneider, Jörg W. (2019-06-01). "A new mesenosaurine from the lower Permian of Germany and the postcrania of Mesenosaurus: implications for early amniote comparative osteology". PalZ. 93 (2): 303–344. doi:10.1007/s12542-018-0439-z. ISSN 1867-6812.