Jerome, Arizona

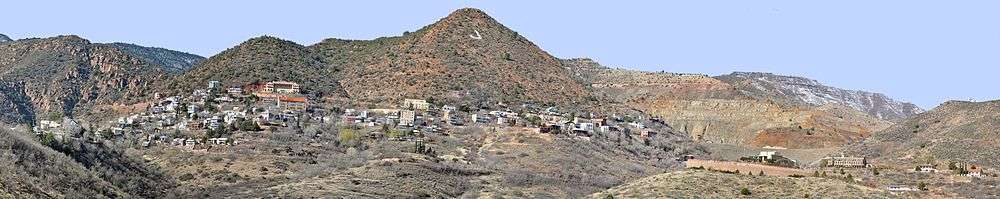

Jerome is a town in the Black Hills of Yavapai County in the U.S. state of Arizona. Founded in the late 19th century on Cleopatra Hill overlooking the Verde Valley, it is more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m) above sea level. It is about 100 miles (160 km) north of Phoenix along State Route 89A between Sedona and Prescott. Supported in its heyday by rich copper mines, it was home to more than 10,000 people in the 1920s. As of the 2010 census, its population was 444.

Jerome, Arizona | |

|---|---|

Town | |

.jpg) Civic Building in 2013 | |

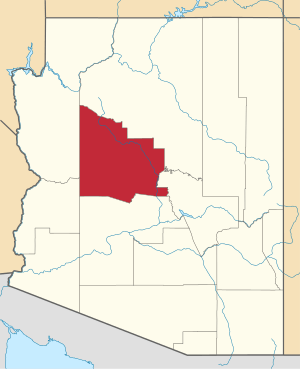

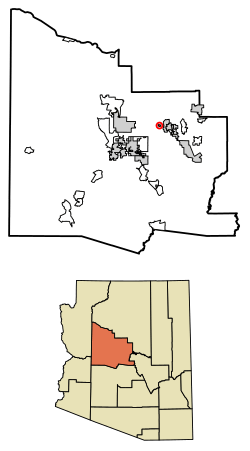

Location of Jerome in Yavapai County, Arizona | |

Jerome Location in Arizona  Jerome Jerome (the United States) | |

| Coordinates: 34°44′56″N 112°06′50″W[1] | |

| Country | |

| State | |

| County | Yavapai |

| Incorporated | 1899 |

| Government | |

| • Mayor | Christina "Alex" Barber |

| Area | |

| • Total | 0.86 sq mi (2.24 km2) |

| • Land | 0.86 sq mi (2.24 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 5,066 ft (1,544 m) |

| Population | |

| • Total | 444 |

| • Estimate (2019)[4] | 455 |

| • Density | 526.62/sq mi (203.36/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-7 (MST) |

| ZIP code[5] | 86331 |

| Area code(s) | 928 |

| FIPS code[6] | 04-36290 |

| GNIS feature ID | 30522 |

| Website | Town of Jerome |

| Population density has been calculated by dividing population by land area and rounding to the nearest hundred per square mile. | |

The town owes its existence mainly to two ore bodies that formed about 1.75 billion years ago along a ring fault in the caldera of an undersea volcano. Tectonic plate movements, plate collisions, uplift, deposition, erosion, and other geologic processes eventually exposed the tip of one of the ore bodies and pushed the other close to the surface, both near Jerome. In the late 19th century, the United Verde Mine, developed by William A. Clark, extracted ore bearing copper, gold, silver, and other metals from the larger of the two. The United Verde Extension UVX Mine, owned by James Douglas, Jr., depended on the other huge deposit. In total, the copper deposits discovered in the vicinity of Jerome were among the richest ever found.

Jerome made news in 1917, when strikes involving the Industrial Workers of the World (IWW) led to the expulsion at gunpoint of about 60 IWW members, who were loaded on a cattle car and shipped west. Production at the mines, always subject to fluctuations, boomed during World War I, fell thereafter, rose again, then fell again during and after the Great Depression. As the ore deposits ran out, the mines closed, and the population dwindled to fewer than 100 by the mid-1950s. Efforts to save the town from oblivion succeeded when residents turned to tourism and retail sales. Jerome became a National Historic Landmark in 1967. By the early 21st century, Jerome had art galleries, coffee houses, restaurants, a state park, and a local museum devoted to mining history.

Geography

Jerome is about 100 miles (160 km) north of Phoenix and 45 miles (72 km) southwest of Flagstaff along Arizona State Route 89A between Sedona to the east and Prescott to the west.[7] The town is in Arizona's Black Hills, which trend north–south. The town lies within the Prescott National Forest[8] at an elevation of more than 5,000 feet (1,500 m).[1] Woodchute Wilderness is about 3 miles (5 km) west of Jerome,[8] and Mingus Mountain, at 7,726 feet (2,355 m) above sea level,[9] is about 4 miles (6 km) south of town.[8] Jerome State Historic Park is in the town itself. Bitter Creek, a tributary of the Verde River, flows intermittently through Jerome.[10] East of Jerome at the base of the hills are the Verde Valley and the communities of Clarkdale and Cottonwood,[8] site of the nearest airport.[11]

Geology

Most of Cleopatra Hill, the rock formation upon which Jerome was built, is 1.75 billion (1,750 million) years old.[12] Created by a massive caldera eruption in Precambrian[12]—elsewhere more narrowly identified as Proterozoic[13]—seas south of what later became northern Arizona, the Cleopatra tuff was then part of a small tectonic plate that was moving toward the proto-North American continent.[12] After the eruption, cold sea water entered Earth's crust through cracks caused by the eruption. Heated by rising magma to 660 °F (350 °C) or more, the water was forced upward again, chemically altering the rocks it encountered and becoming rich in dissolved minerals. When the hot solution emerged from a hydrothermal vent at the bottom of the ocean, its dissolved minerals solidified and fell to the sea floor. The accumulating sulfide deposits from two such vents formed the ore bodies, the United Verde and the UVX, most important to Jerome 1.75 billion years later.[12]

These ore bodies formed in different places along a ring fault in the caldera. About 50 million years after they were deposited, the tectonic plate of which they were a part collided with another small plate and then with the proto-North American continent. The collisions, which welded the plates to the continent, folded the Cleopatra tuff in such a way that the two ore bodies ended up on opposite sides of a fold called the Jerome anticline.[12]

No record exists for the next 1.2 billion years of Jerome's geologic history.[12] Evidence from the Grand Canyon, further north in Arizona, suggests that thick layers of sediment may have been laid down atop the ore bodies and later eroded away.[14] The gap in the rock record has been called the Great Unconformity.[15]

About 525 million years ago, when northern Arizona was at the bottom of a shallow sea, a thin layer of sediment called the Tapeats Sandstone was deposited over the Cleopatra tuff. Limestones and other sediments accumulated above the sandstone until about 70 million years ago when the Laramide Orogeny created new mountains and new faults in the region. One of these faults, the Verde Fault, runs directly under Jerome along the Jerome anticline. Crustal stretching beginning about 15 million years ago created Basin and Range topography in central and southern Arizona, caused volcanic activity near Jerome, and induced movement along the Verde Fault. This movement exposed the tip of the United Verde ore body at one place on Cleopatra Hill and moved the UVX ore body to 1,000 feet (300 m) below the surface. Basalt, laid down between 15 and 10 million years ago, covers the surface beneath the UVX headframes and Jerome State Historic Park. The basalt, the top layer of the Hickey Formation,[12] caps layers of sedimentary rock.[16]

The natural rock features in and around Jerome were greatly altered by mining. The town is underlain by 88 miles (142 km) of mine shafts. These may have contributed to the subsidence that destroyed some of Jerome's buildings, which slid slowly downhill during the first half of the 20th century. The United Verde open pit, about 300 feet (91 m) deep, is on the edge of town next to Cleopatra Hill. The side of the pit consists of Precambrian gabbro. Mine shafts beneath the pit extend to 4,200 feet (1,300 m) below the surface.[12]

History

Early

The Hohokam were the first people known to have lived and farmed near Jerome from 700 to 1125 BCE.[17] Later, long before the arrival of Europeans, it is likely that other native peoples mined the United Verde ore body for the colorful copper-bearing minerals malachite and azurite. The top of the ore body was accessible because it was visible on the surface.[12]

The first Europeans to arrive in the area were the Spanish conquistadors. At the time the area was part of "New Mexico", and the Spaniards often organized silver and gold prospecting expeditions in the area. In 1585, Spanish explorers made note of the ore[12] but did not mine it because their government had sent them to find gold and silver, not copper.[17]

19th century

The area became part of Mexico when Mexico gained its independence from Spain in 1821,[18] and part of the United States by terms of the 1848 Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo, which concluded the Mexican–American War. The war's major consequence was the Mexican Cession of the northern territories of Alta California and Santa Fe de Nuevo México to the United States.[19]

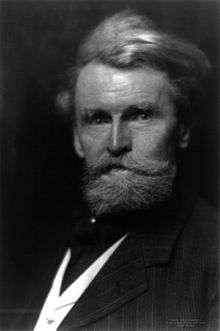

Angus McKinnon and Morris A. Ruffner filed the first copper mining claims at this location in 1876.[20] In 1880, Frederick A. Tritle, the governor of the Arizona Territory, and Frederick F. Thomas, a mining engineer from San Francisco, bought these claims from the original owners. In 1883, with the aid of eastern financiers including James A. MacDonald and Eugene Jerome of New York City, they created the United Verde Copper Company. The small adjacent mining camp on Cleopatra Hill was named Jerome in honor of Eugene Jerome, who became the company secretary.[lower-alpha 1] United Verde built a small smelter at Jerome and constructed wagon roads from it to Prescott, the Verde Valley, and the Atlantic and Pacific Railroad depot at Ash Fork. However, transport by wagon was expensive, and in late 1884 after the price of copper had fallen by 50 percent, the company ceased all operations at the site.[21]

Four years later, William A. Clark, who had made a fortune in mining and commercial ventures in Montana, bought the United Verde properties and, among other improvements, enlarged the smelter.[21] He ordered construction of a narrow gauge railway, the United Verde & Pacific, to Jerome Junction, a railway transfer point 27 miles (43 km) to the west.[22] As mining of the ore expanded, Jerome's population grew from 250 in 1890 to more than 2,500 by 1900. By then the United Verde Mine had become the leading copper producer in the Arizona Territory, employing about 800 men,[21] and was one of the largest mines in the world.[23] Over its 77-year life (1876 to 1953), this mine produced nearly 33 million tons of copper, gold, silver, lead and zinc ore.[12] The metals produced by United Verde and UVX, the other big mine in Jerome, were said to be worth more than $1 billion.[24][lower-alpha 2] According to geologists Lon Abbott and Terri Cook, the combined copper deposits of Jerome were among the richest ever found.[26]

Jerome had a post office by 1883. It added a schoolhouse in 1884 and a public library in 1889. After four major fires between 1894 and 1898 destroyed much of the business district and half of the community's homes, Jerome was incorporated as a town in 1899.[27] Incorporation made it possible to collect taxes to build a formal fire-fighting system and to establish building codes that prohibited tents and other fire hazards within the town limits.[28] Local merchant and rancher William Munds was the first mayor.[29]

By 1900, Jerome had churches, fraternal organizations, and a downtown with brick buildings, telephone service, and electric lights.[21] Among the thriving businesses were those associated with alcohol, gambling, and prostitution serving a population that was 78 percent male.[30] In 1903, the New York Sun proclaimed Jerome to be "the wickedest town in the West".[31]

Early 20th century

Jerome, which was legally separate from United Verde and supported many independent businesses, did not meet the definition of a company town[32] even though it depended for decades largely on a single company. In 1914, a separate company, the United Verde Extension Mining Company (UVX), led by James S. Douglas, Jr. (nicknamed Rawhide Jimmy), discovered a second ore body near Jerome that produced a bonanza.[33] The UVX Mine, also known as the Little Daisy Mine,[34] became spectacularly profitable: during 1916 alone, it produced $10 million worth of copper, silver and gold, of which $7.4 million was profit.[35] This mine eventually produced more than $125 million worth of ore and paid more than $50 million in dividends.[33] Total production amounted to four million tons, much less than the United Verde total but from uncommonly rich ore averaging more than 10 percent copper and in places rising to 45 percent.[12]

.png)

Starting in 1914, World War I greatly increased the demand for copper, and by 1916 the number of companies involved in mining near Jerome reached 22.[36] These companies employed about 3,000 miners in the district.[36] Meanwhile, United Verde was building a large smelter complex and company town, Clarkdale, and a standard gauge railway, the Verde Tunnel and Smelter Railroad, to haul ore from its mine to the new smelter.[37] After the new railway opened in 1915, the company dismantled the Jerome smelter and converted the mine to an open-pit operation by 1919.[38][lower-alpha 3] The switch from underground to open-pit mining stemmed from a series of fires, some burning for decades, in the mine's high-sulfur ores. Removing the overburden and pouring a mixture of water, waste ore, and sand into rock fissures helped control the fires.[41] By 1918, UVX also had its own smelter in its own company town near Cottonwood; the company town was named Clemenceau in 1920.[38] In 1929, a company named Verde Central opened what at first appeared to be another "great mine"[42] about a mile southwest of Jerome.[43]

The labor situation in Jerome was complicated. Three separate labor unions—the International Union of Mine, Mill, and Smelter Workers (MMSW), the Industrial Workers of the World or IWW, and the Liga Protectora Latina, which represented about 500 Mexican miners—had members in Jerome. In 1917, two miners' strikes involving the IWW, which had been organizing strikes elsewhere in Arizona and other states, took place in Jerome. Seen as a threat by business interests as well as other labor unions, the Wobblies, as they were called, were subject nationally to sometimes violent harassment. The MMSW, which in May called a strike against United Verde, regarded the rival IWW with animosity and would not recognize it as legitimate. In response, the IWW members threatened to break the strike. Under pressure, the MMSW voted 467 to 431 to settle for less than they wanted.[44]

In July, the IWW called for a strike against all the mines in the district. In this case, the MMSW voted 470 to 194 against striking. Three days later, about 250 armed vigilantes rounded up at least 60 suspected IWW members, loaded them onto a railroad cattle car, and shipped them out of town in what has been called the Jerome Deportation. Nine IWW members, thought by the Prescott sheriff's department to be leaders, were arrested and jailed temporarily in Prescott though never charged with a crime; others were taken to Needles, California, then to Kingman, Arizona, where they were released after promising to desist from "further agitation".[44]

After 1920

Following a brief post-war downturn, boom times returned to Jerome in the 1920s. Copper prices rose to 24 cents a pound in 1929,[45] and United Verde and UVX operated at near capacity.[46] Wages rose, consumers spent, and the town's businesses—including five automobile dealerships—prospered.[47] United Verde, seeking stable labor relations, added disability and life insurance benefits for its workers and built a baseball field, tennis courts, swimming pools, and a public park in Jerome. Both companies donated to the Jerome Public Library and helped finance projects for the town's schools, churches, and hospitals.[48]

In 1930, after the start of the Great Depression, the price of copper fell to 14 cents a pound.[49] In response, United Verde began reducing its work force; UVX operated at a loss, and the third big mine, Verde Central, closed completely.[50] The price of copper fell further in 1932 to 5 cents a pound, leading to layoffs, temporary shut-downs, and wage reductions in the Verde District.[51] In 1935, the Clark family sold United Verde to Phelps Dodge,[52] and in 1938 UVX went out of business.[53]

Meanwhile, a subsidence problem that had irreparably damaged at least 10 downtown buildings by 1928 worsened through the 1930s. Dozens of buildings, including the post office and jail, were lost as the earth beneath them sank away.[lower-alpha 4] Contributing causes were geologic faulting in the area, blast vibrations from the mines, and erosion that may have been exacerbated by vegetation-killing smelter smoke.[55][lower-alpha 5]

Mining continued at a reduced level in the Verde District until 1953, when Phelps Dodge shut down the United Verde Mine and related operations. Jerome's population subsequently fell below 100.[20] To prevent the town from disappearing completely, its remaining residents turned to tourism and retail sales. They organized the Jerome Historical Society in 1953 and opened a museum and gift shop.[58]

To encourage tourism, the town's leaders sought National Historic Landmark status for Jerome; it was granted by the federal government in 1967.[59] In 1962, the heirs of James Douglas donated the Douglas mansion, above the UVX mine site, to the State of Arizona, which used it to create Jerome State Historic Park.[34] By sponsoring music festivals, historic-homes tours, celebrations, and races, the community succeeded in attracting visitors and new businesses, which in the 21st century include art galleries, craft stores, wineries, coffee houses, and restaurants.[58]

Climate

July is typically the warmest month in Jerome, when highs average 90 °F (32 °C) and lows average 67 °F (19 °C). January is coldest, when the high temperatures average 50 °F (10 °C) and the lows average 33 °F (1 °C). The highest recorded temperature through 2005 was 108 °F (42 °C) in 2003, and the lowest was 5 °F (−15 °C) in 1963. August, averaging about 3 inches (76 mm) of rain, is the wettest month, while the spring months of April to June generally do not have significant rainfall.[60]

Although most precipitation arrives in the town as rain, snow and fog sometimes occur.[61] On average, about 5 inches (13 cm) of snow falls in January and lesser amounts in February, March, April, November, and December.[60] Even so, the average depth of snow on the ground between 1897 and 2005 was so close to zero that it is reported as zero.[60] Jerome is often windy, especially in spring and fall.[61] Summer thunderstorms can be violent.[61]

According to the Köppen climate classification, Jerome has a Mediterranean climate (Csa).

| Climate data for Jerome, Arizona (1897–2005) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °F (°C) | 75 (24) |

82 (28) |

85 (29) |

92 (33) |

99 (37) |

104 (40) |

108 (42) |

105 (41) |

102 (39) |

94 (34) |

85 (29) |

75 (24) |

108 (42) |

| Average high °F (°C) | 51 (11) |

54 (12) |

60 (16) |

68 (20) |

77 (25) |

87 (31) |

90 (32) |

87 (31) |

83 (28) |

72 (22) |

60 (16) |

52 (11) |

70 (21) |

| Average low °F (°C) | 33 (1) |

35 (2) |

39 (4) |

45 (7) |

54 (12) |

63 (17) |

67 (19) |

65 (18) |

61 (16) |

51 (11) |

41 (5) |

34 (1) |

49 (9) |

| Record low °F (°C) | 5 (−15) |

8 (−13) |

17 (−8) |

23 (−5) |

26 (−3) |

39 (4) |

44 (7) |

31 (−1) |

40 (4) |

21 (−6) |

16 (−9) |

5 (−15) |

5 (−15) |

| Average precipitation inches (mm) | 1.74 (44) |

1.88 (48) |

1.77 (45) |

1.06 (27) |

0.57 (14) |

0.40 (10) |

2.56 (65) |

3.12 (79) |

1.46 (37) |

1.26 (32) |

1.25 (32) |

1.49 (38) |

18.56 (471) |

| Source: Western Regional Climate Center[60] | |||||||||||||

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1890 | 250 | — | |

| 1900 | 2,861 | 1,044.4% | |

| 1910 | 2,393 | −16.4% | |

| 1920 | 4,030 | 68.4% | |

| 1930 | 4,932 | 22.4% | |

| 1940 | 2,295 | −53.5% | |

| 1950 | 1,233 | −46.3% | |

| 1960 | 243 | −80.3% | |

| 1970 | 290 | 19.3% | |

| 1980 | 420 | 44.8% | |

| 1990 | 403 | −4.0% | |

| 2000 | 329 | −18.4% | |

| 2010 | 444 | 35.0% | |

| Est. 2019 | 455 | [4] | 2.5% |

| Census sources 1890–1990,[62] 2000 and 2010[3] | |||

The makeup of early Jerome differed greatly from the 21st-century version of the town. The original mining claims were filed by North American ranchers and prospectors, but as the mines were developed, workers of varied ethnic groups and nationalities arrived. Among these were people of Irish, Chinese, Italian, and Slavic origin who came to Jerome in the late 19th century. By the time of World War I, Mexican nationals were arriving in large numbers, and census figures suggest that in 1930 about 60 percent of the town's residents were Latino.[63] This statistic is supported by mining company records showing that about 57 percent of the UVX workers were Mexican nationals in 1931 and that foreign-born and Spanish-surnamed workers accounted for about 77 percent of the UVX work force.[64]

The ratio of females to males also varied greatly over time in Jerome. Census data from 1900 through 1950 show a gradual rise in the percentage of female residents, who accounted for only 22 percent of the population at the turn of the century but about 50 percent by mid-century.[65]

As of the census of 2010, Jerome was home to 444 people comprising 253 households, 93 of which were families made up of a householder and one or more people related to the householder by birth, marriage, or adoption. The other 160 were non-family. The residents had a racial makeup that was nearly 94 percent white, and the remainder were listed in the census as black or African American, Native American, Asian, other, or combinations thereof. About 6 percent of the population were Hispanic or Latino of any race. The population, nearly evenly split along gender lines, consisted of 226 women with a median age of 54 and 218 men with a median age of 55. The estimated population in 2015 was 456.[3]

As of 2014, the median income for a household in the town was about $32,000.[3] About 10 percent of families in Jerome had incomes below the poverty line in 2014.[3]

Government

Jerome has a mayor–council government. The five seats on the council are filled by public election once every two years, and the council member receiving the most votes in that election becomes the mayor.[67] Frank Vander Horst, elected in 2016, is the mayor through 2018.[68]

Yavapai County typically elects Republicans to state and federal offices.[69] About 64 percent of its participating voters chose Republican Mitt Romney for president in 2012,[69] and about 63 percent chose Republican Donald Trump in 2016.[70] At the state level, Walter Blackman and Bob Thorpe, both Republicans, represent Jerome as part of the Sixth Legislative District of the Arizona Legislature. Republican Sylvia Allen represents the Sixth District in the Arizona Senate.[71][72] At the federal level, Republican Paul Gosar represents Jerome and the rest of Arizona's Fourth Congressional District in the United States House of Representatives. Republican Martha McSally and Kyrsten Sinema, a Democrat, represent Arizona in the United States Senate.[73]

The town is patrolled by its own police department[74] and is also served by the Eastern Area Command of the Yavapai County Sheriff's Office.[75] About two dozen men and women comprise Jerome's volunteer fire department, which serves an area of more than 500 square miles (1,300 km2) including nearby rural and mountainous terrain as well as the town itself. Firefighting, emergency medical service, and wilderness rescues are its specialties.[76] Jerome is in the Verde Valley Precinct of the Yavapai County Justice Court system.[77]

In 2013, Jerome was the third municipality in Arizona to recognize civil unions between same-sex partners, after Bisbee and Tucson.[78]

Economy and culture

Jerome's economy is centered mainly on recreation and tourism. Figures published in 2015 showed that more than 50 percent of the labor force worked in arts, entertainment, retail, food and recreation services, while manufacturing and construction employed just over 10 percent.[79] Between 1990 and 2006 the value of taxable sales increased from $4.8 million to $15.5 million,[80] and between 1990 and 2014 the unemployment rate fell from 4.2 percent to 1.4 percent.[79] Formerly vacant buildings house boutiques, gift shops, antique and craft shops;[80] the town also has five art galleries, a library, three parks and two museums, including the Mine Museum run by the Jerome Historical Society,[79] and a former church building that houses the society's offices and archives.[81] Annual events include a home tour ("Paso de Casas") in May, a reunion for former mining families in October, and a Festival of Lights in December.[80] Gulch Radio KZRJ broadcasts from Jerome at 100.5 FM and streams online.[82] The Town of Jerome publishes a bi-monthly newsletter, Point of View.[83]

Infrastructure

School buildings

.jpg)

Children from Jerome in kindergarten through eighth grade attend the Clarkdale–Jerome School in Clarkdale.[84] Older students from Jerome are enrolled at Mingus Union High School in Cottonwood.[85] Each of these communities had its own schools during the first half of the 20th century,[85] but declining populations and shrinking tax revenues led to consolidation.[86] The former Jerome High School complex is home in the 21st century to many artists' galleries.[87]

Sliding jail

In March 2017, the Jerome Historical Society acquired the former jail, now known as the Sliding Jail, from the Town of Jerome. Rendered unusable but not completely destroyed by earth movements since the 1930s, the jail is about 200 feet (60 m) downhill from where it was originally built. The society plans to rehabilitate the jail, which has become a popular tourist attraction. The project, including improvements to a sliding parking area nearby, is expected to be completed later in 2017.[88]

Utilities

Jerome manages its own water system,[89] sourced by ten mountain springs.[90] The town's annual water report for 2016 assured residents that Jerome's water met all state and federal requirements and was safe to drink.[90] Jerome administers its own sewer system, trash collection, and recycling services.[91] Its public works department maintains the equipment and infrastructure associated with these systems as well the water system, streets, parks, and other city property.[91]

Arizona Public Service provides electricity to Jerome, and UniSource Energy Services is the supplier of natural gas.[92] Century Link (DSL), HughesNet (satellite), Speed Connect (fixed wireless), and mobile Web providers offer Internet access.[93] Satellite television is available via DirecTV and the Dish Network.[93] Mobile phone companies and Century Link offer telephone services.[92]

Notable people

- Maynard James Keenan, singer for Tool (progressive-metal band), A Perfect Circle and Puscifer. Founder of Caduceus Cellars wine.[94]

- Katie Lee, folk singer[95]

- Fred Rico, major league baseball player[96]

In popular culture

- The novel Muckers (2013) by Sandra Neil Wallace, a former sportscaster for ESPN, is a historical novel for young adults that is based on the Jerome High School football team of 1950. The team went undefeated that year, shortly before the copper mine closed and Jerome's population dwindled.[97][98][99]

- The Barenaked Ladies song "Jerome" focuses on the town's reputation for being haunted, and also references the Sliding Jail and other points of interest in local geography, culture, and history.[100]

Notes and references

Notes

- Jerome was a cousin of Winston Churchill's mother, Jennie Jerome.[20]

- Historian Eric Clements suggests that the billion-dollar claim stemmed partly from boosterism and that "actual production never justified such a boast."[25] Geologists Lon Abbott and Terri Cook reckon the value of the metals from United Verde and UVX would have risen to $4 billion in "today's market" (2007), $3 billion from copper alone and $1 billion total from the other four metals.[26]

- The decision to turn the United Verde Mine into an open-pit operation led to abandonment of the narrow-gauge United Verde & Pacific Railway between Jerome and Jerome Junction.[37] Instead, the 11-mile (18 km) Verde Tunnel & Smelter Railroad (VT&S) and a companion electric line, the Hopewell Haulage Railroad, transported ore to Clark's new smelter from two different levels of the mine. The electric train, the lower of the two, ran through the 7,200-foot (2,200 m) Hopewell Tunnel to a station called Hopewell, where ore was transferred to the VT&S.[39] In 1922, UVX owner Douglas built his own shortline railroad, the 8-mile (13 km) Arizona-Extension Railway. It began at the east entrance to the 2.5-mile (4.0 km) Josephine Tunnel, through which electric trains transported ore from the UVX Mine for transfer to the shortline and thence to the UVX smelter at Clemenceau.[40]

- Jerome's housing stock and other buildings met a wide variety of fates over the years. Some burned or collapsed. Some were moved intact or in pieces to places as far away as Flagstaff. After 1953, through the efforts of the Jerome Historical Society and others, some like the Boyd Hotel, the Powder Box Church, and the Fourth Hospital (now the Grand Hotel and Asylum Restaurant) were restored. Not every standing building has been completely restored, and ruins are still visible in "Mexican Town", downhill from the main business district.[54]

- Pine, oak, and manzanita trees covered Jerome until the late 19th century but were cut down for mine timbers and other lumber.[56] In 1964, Cleopatra Hill was seeded with ailanthus trees to limit severe erosion from the denuded slopes.[57]

References

- "Jerome". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. February 8, 1980. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- "2019 U.S. Gazetteer Files". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved June 30, 2020.

- "U.S. Census website". United States Census Bureau. Retrieved April 19, 2017.

- "Population and Housing Unit Estimates". United States Census Bureau. May 24, 2020. Retrieved May 27, 2020.

- "Jerome, AZ". Look Up a Zipcode. United States Post Office. 2017. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- "Geographies: Jerome Town, Arizona". United States Census Bureau. 2016. Archived from the original on August 22, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- The 2013 Road Atlas (Map). Chicago: Rand McNally & Company. § 8–9. ISBN 978-0-528-00622-7.

- Arizona Atlas & Gazetteer (Map). Yarmouth, ME: DeLorme. 2008. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-89933-325-0.

- "Mingus Mountain". Geographic Names Information System. United States Geological Survey. February 8, 1980. Retrieved October 23, 2012.

- United States Geological Survey. "United States Topographic Map". TopoQuest. Retrieved October 7, 2012.

- "Jerome". Arizona Department of Commerce. 2007. Archived from the original on May 16, 2018. Retrieved June 4, 2017.

- Abbott & Cook 2007, pp. 233–47.

- "Hofstra University Field Trip Guidebook: Geology 143A – Field Geology of Northern Arizona" (PDF). Duke Geological Laboratory. 2010. p. 6. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 3, 2017. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- Berthault, G. (2004). "Sedimentological Interpretation of the Tonto Group Stratigraphy (Grand Canyon Colorado River" (PDF). Lithology and Mineral Resources. 39 (5): 481–82. doi:10.1023/B:LIMI.0000040737.85572.4c. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 12, 2017. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- "Tapeats Sandstone". United State Geological Survey. May 3, 2017. Archived from the original on February 12, 2018. Retrieved May 16, 2017.

- Brand, P.K.; Stump, E. (2005). "Hickey Formation". Arizona Geological Survey. Archived from the original on April 20, 2017. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- "Town History". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on April 10, 2018. Retrieved May 4, 2017.

- "Diez y Seis Salutes Mexican Heritage". The Seguin Gazette-Enterprise. September 8, 1994. Retrieved May 15, 2018 – via Newspapers.com.

- "Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo; February 2, 1848". The Avalon Project. Lillian Goldman Law Library, Yale University. 2008. Archived from the original on November 20, 2017. Retrieved May 15, 2018.

- Steuber 2008, p. 10.

- Clements 2003, pp. 45–47.

- Steuber 2008, p. 48.

- Alenius, E.M.J. (1968). "A Brief History of the United Verde Open Pit: Bulletin 178" (PDF). The Arizona Bureau of Mines. p. iii. Archived (PDF) from the original on February 9, 2017. Retrieved April 21, 2017.

- Steuber 2008, p. 7.

- Clements 2003, p. 2.

- Abbott & Cook 2007, p. 235.

- Steuber 2008, p. 82.

- Steuber 2008, p. 101.

- Steuber 2008, p. 17.

- Steuber 2008, p. 63.

- Price, Michael (January 17, 2007). "Jerome: A Ghost Town That Never Gave Up the Ghost". Geotimes. American Geological Institute. Archived from the original on April 12, 2013. Retrieved October 8, 2012.

- Clements 2003, p. 294.

- Clements 2003, pp. 47–49.

- Steuber 2008, p. 123.

- Arizona Bureau of Mines; U.S. Geological Survey (1969). Mineral and Water Resources of Arizona: Bulletin 180, Part 2: Mineral Fuels and Associated Resources (PDF). Arizona Geological Survey. pp. 127–28. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 10, 2018.

- Clements 2003, p. 48.

- Wahmann 1999, p. 15.

- Clements 2003, p. 49.

- Wahmann 1999, pp. 27, 29, 41.

- Wahmann 1999, p. 61.

- Corporation, Bonnier (January 1931). "Work Mine in Spite of Old Fire". Popular Science. 118 (1): 26, 142. ISSN 0161-7370. Retrieved October 17, 2012 – via Google Books.

- Clements 2003, p. 44.

- "Verde Central Mine". United States Geological Survey. Retrieved May 29, 2017.

- Lindquist, John H. (Autumn 1969). "The Jerome Deportation of 1917". Arizona and the West. Journal of the Southwest. 11 (3): 233–46. ISSN 0004-1408. JSTOR 40167537.

- Clements 2003, p. 51.

- Clements 2003, p. 53.

- Clements 2003, p. 45.

- Clements 2003, pp. 54–55.

- Clements 2003, p. 84.

- Clements 2003, p. 85.

- Clements 2003, p. 88.

- Clements 2003, p. 90.

- Clements 2003, p. 92.

- Steuber 2008, pp. 103–22.

- Clements 2003, p. 197.

- Steuber 2008, p. 81.

- Steuber 2008, p. 115.

- Clements 2003, p. 251.

- Steuber 2008, p. 8.

- "Jerome, Arizona (024453)". Western Regional Climate Center. Retrieved April 20, 2017. Maximum highs and lows are included in the table labeled "Temperature" under the heading "General Climate Summary Tables" in the left-hand column.

- "Jerome State Historic Park: Weather". Arizona State Parks. Archived from the original on March 19, 2015. Retrieved January 15, 2013.

- Moffat 1996, p. 12.

- Clements 2003, pp. 59–60.

- Clements 2003, p. 149.

- Clements 2003, p. 153.

- Steuber 2008, p. 95.

- Tracey, Tom (September 1, 2016). "Will Jerome See 'Out with the Old, in with the Old?'". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Tracey, Tom (November 13, 2016). "Changing of the Guard in Jerome". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. Archived from the original on November 14, 2016. Retrieved April 18, 2017.

- Joffe-Block, Jude (September 13, 2016). "Is Arizona a Swing State This Year". National Public Radio. Archived from the original on December 24, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- "Election Results: Yavapai County". The Daily Courier. The Daily Courier and Western News&Info. November 9, 2016. Archived from the original on November 10, 2016. Retrieved May 27, 2017.

- "District Locator". Arizona Independent Redistricting Commission. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- "Member Roster". Arizona State Legislature. Retrieved May 9, 2017.

- "Arizona's 4th Congressional District". GovTrack. Civic Impulse. Retrieved January 4, 2019.

- "Police Department". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Yavapai County Sheriff's Office: Area Command Map". Yavapai County. 2017. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- "Fire Department". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Yavapai County Justice Court Precincts". Yavapai County Government. Archived from the original on March 22, 2015. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- Lineberger, Mark (September 16, 2013). "Jerome OKs Civil Unions". journalaz.com. Retrieved July 27, 2018.

- "Community Profile for Jerome". Arizona Commerce Authority. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Jerome". Arizona Department of Commerce. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Offices and Archives". Jerome Historical Society. 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Gulch Radio: Jerome, Arizona". Gulch Radio Playlist. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Town Newsletter". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on November 29, 2016. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Clarkdale Jerome School Page". Clarkdale–Jerome School. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- Wright, Philip (June 24, 2011). "Historical Societies Receive High School Annuals". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017. Retrieved October 25, 2012.

- Clements 2003, p. 220.

- "Sedona Verde Valley: Old Jerome High School". National Geographic Travel Guide. Old Town Creative and Interactive. Retrieved May 6, 2017.

- Starinskas, Vito (March 4, 2017). "Jerome's Sliding Jail: Town Turns Landmark Over to Jerome Historical Society". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. Retrieved June 6, 2017.

- "Utilities". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Home Page". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on 2016-11-18. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Public Works". Town of Jerome. 2017. Archived from the original on November 18, 2016. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Welcome to Sedona and Verde Valley: Cottonwood/Clarkdale/Jerome/Cornville Utilities". Verde Valley Newspapers and Western News&Info. 2017. Archived from the original on 2016-03-23. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "Internet Providers in 86331 (Jerome, AZ) & Cable/TV Companies". DecisionData. Retrieved May 8, 2017.

- "How Maynard James Keenan Is Building a Community Through Art and Work". Revolver. September 21, 2017. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- Wright, Philip (September 20, 2011). "An Arizona Legend: Jerome's Katie Lee to Be Inducted into Arizona Music Hall of Fame". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. Archived from the original on May 5, 2017. Retrieved October 22, 2012.

- Reichler, Joseph L., ed. (1979) [1969]. The Baseball Encyclopedia (4th ed.). New York: Macmillan Publishing. p. 1325. ISBN 978-0-02-578970-8.

- "Muckers". Goodreads. Archived from the original on April 23, 2015. Retrieved July 14, 2014.

- "Muckers Tells Jerome-Inspired Story of Arizona Football Triumph". Verde Independent. Western News&Info. October 7, 2013. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- Dare, Kim (December 4, 2013). "Pick of the Day: Muckers". School Library Journal. Retrieved May 28, 2017.

- Kevin Hearn, Barenaked Ladies, "Jerome," All in Good Time (Barenaked Ladies album), Raisin' Records, 2010

Sources

- Abbott, Lon; Cook, Terri (2007). Geology Underfoot in Northern Arizona. Missoula, MT: Mountain Press Publishing. ISBN 978-0-87842-528-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Clements, Eric L. (2003). After the Boom in Tombstone and Jerome, Arizona: Decline in Western Resource Towns. Reno, NV: University of Nevada Press. ISBN 978-0-87417-571-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Moffat, Riley Moore (1996). Population History of Western U.S. Cities and Towns, 1850–1990. Lanham, MD: Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-3033-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Steuber, Midge (2008). Images of America: Jerome. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7385-5882-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wahmann, Russell (1999). Verde Valley Railroads: Trestles, Tunnels & Tracks. Jerome, AZ: Jerome Historical Society. ISBN 978-0-9621000-4-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Jerome, Arizona. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Jerome (Arizona). |

_pano.jpg)