Concrete art

Concrete art was an art movement with a strong emphasis on geometrical abstraction. The term was first formulated by Theo van Doesburg and was then used by him in 1930 to define the difference between his vision of art and that of other abstract artists of the time. After his death in 1931, the term was further defined and popularized by Max Bill, who organized the first international exhibition in 1944 and went on to help promote the style in Latin America. The term was taken up widely after World War 2 and promoted through a number of international exhibitions and art movements.

Origination

After the formal break up of De stijl, following the last issue of its magazine in 1928, van Doesburg began considering the creation of a new collective centered on a similar approach to abstraction. In 1929 he discussed his plans with Uruguayan painter Joaquín Torres-García, with candidates for membership of this group including Georges Vantongerloo, Constantin Brancusi, František Kupka, Piet Mondrian, Friedrich Vordemberge-Gildewart and Antoine Pevsner, among others. However, van Doesburg divided the candidates between artists whose work was still not completely abstract and those free of referentiality. As this classification entailed the possibility of a disqualification of the first group, the discussions between the two soon broke down, prompting Torres-García to team up instead with Belgian critic Michel Seuphor and form the group Cercle et Carré.[1]

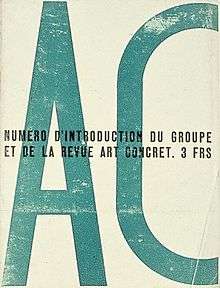

Following this, van Doesburg proceeded to propose a rival group, Art Concret, championing a geometrical abstract art closely related to the aesthetics of Neo-plasticism. In his opinion, the term 'abstract' as applied to art had negative connotations; in its place he preferred the more positive term ‘concrete’.[2] Van Doesburg was eventually joined by Otto G. Carlsund, Léon Arthur Tutundjian, Jean Hélion and his fellow lodger, the typographer Marcel Wantz (1911-79), who soon left to take up a political career.[3] In May 1930 they published a single issue of their own French-language magazine, Revue Art Concret, which featured a joint manifesto, positioning them as the more radical group of abstractionists.

"BASIS OF CONCRETE PAINTING

We say:

- Art is universal.

- A work of art must be entirely conceived and shaped by the mind before its execution. It shall not receive anything of nature’s or sensuality’s or sentimentality’s formal data. We want to exclude lyricism, drama, symbolism, and so on.

- The painting must be entirely built up with purely plastic elements, namely surfaces and colors. A pictorial element does not have any meaning beyond “itself”; as a consequence, a painting does not have any meaning other than “itself”.

- The construction of a painting, as well as that of its elements, must be simple and visually controllable.

- The painting technique must be mechanic, i.e., exact, anti-impressionistic.

- An effort toward absolute clarity is mandatory."[4]

The group was short lived and only exhibited together on three occasions in 1930 as part of larger group exhibitions, the first being at the Salon des Surindépendents in June, followed by Production Paris 1930 in Zürich, and in August the exhibition AC: Internationell utställning av postkubistisk konst (International exhibition of post-cubist art) in Stockholm, curated by Carlsund. In the catalog to the latter, Carlsund states that the group's "programme is clear: absolute Purism. Neo-Plasticism, Purism and Constructivism combined".[5] Shortly before van Doesburg's death in 1931, the members of the Art Concret group still active in Paris united with the larger association Abstraction-Création.

Theoretical background

In 1930, Michel Seuphor had defined the role of the abstract artist in the first issue of Cercle et Carré. It was “to establish, on the foundations of a structure that is simple, severe and unadorned in every part, and within a basis of unconcealed narrow unity with this structure, an architecture which, using the technical means available to its period, expresses in a clear language that which is truly immanent and immutable.”[6] The art historian Werner Haftmann traces the development of the pure abstraction proposed by Seuphor to the synthesis of Russian Constructivism and Dutch Neo-Plasticism in the Bauhaus, where painting abandoned the artificiality of representation for technological authenticity. “In close connection with architecture and engineering, art should endeavour to give form to life itself … [The former] provided new sources of inspiration as well as new materials – steel, aluminium, glass, synthetic materials.”[7]

As van Doesburg had pointed out in his manifesto, in order to be universal, art must abandon subjectivity and find impersonal inspiration purely in the elements of which it is constructed: line, plane and color. Some later artists associated with this tendency, such as Victor Vasarély, Jean Dewasne, Mario Negro and Richard Mortensen, only came to painting after first studying science.[8] Nevertheless, all theoretical advances seek justification in past practice, and in this case the mathematical proportions expressed in abstract form are to be identified in various art forms over millennia. Thus, argued Hartmann, “the elimination of representational images and the overt use of pure geometry do not imply a radical and definitive rejection of the great art of the past, but rather a reassertion of its eternal values stripped of their historical and social disguises.”[9]

Development

While Abstraction-Création was a grouping of all modernistic tendencies, there were those within it who carried the idea of mathematically inspired art and the term ‘concrete art’ to other countries when they moved elsewhere. A key figure among them was Joaquin Torres García, who returned to South America in 1934 and mentored artists there. Some of those went on to found the group Arte Concreto Invención in Buenos Aires in 1945.[11] Another was the designer Max Bill, who had studied at the Bauhaus in 1927-9. After returning to Switzerland, he helped organize the Allianz group to champion the ideals of Concrete Art. In 1944 he organized the first international exhibition in Basle and at the same time founded abstract-konkret, the monthly bulletin of the Gallerie des Eaux Vives in Zurich.[12] By 1960 Bill was organizing a large retrospective exhibition of Concrete Art in Zürich illustrating 50 years of its development.

Abstraction, which had been quietly gathering momentum in Italy between the world wars, emerged officially in the Movimento d'arte concreta (MAC) in 1948, whose foremost exponent, Alberto Magnelli, was another past member of Abstraction-Création and had been living in France for many years. However, some seventy native painters were represented in the Arte astratta e concreta in Italia exhibition held three years later at the National Gallery in Rome.[13] In Paris recognition of this approach resulted in several exhibitions of which the first was titled Art Concret and held at the Gallerie René Drouin during the summer of 1945. Described as "the first major post-World War 2 exhibition of abstract art”,[14] the artists exhibited there included the older generation of abstractionists: Jean Arp, Sophie Taeuber-Arp, Sonia Delaunay, César Domela, Otto Freundlich, Jean Gorin, Auguste Herbin, Wassily Kandinsky, Alberto Magnelli, Piet Mondrian, Antoine Pevsner and van Doesburg. In the following year a series of annual exhibitions began in the Salon des Réalités Nouvelles, which included some of these artists and were devoted, according to its articles of association, to “works of art commonly called: concrete art, non-figurative or abstract art".[15]

In 1951 Groupe Espace was founded in France to harmonize painting, sculpture and architecture as a single discipline. This grouped sculptors and architects with old established artists such as Sonia Delaunay and Jean Gorin and the newly emergent Jean Dewasne and Victor Vasarély. Its manifesto was published in L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui that year and placarded on the streets of Paris, championing the fundamental presence of the plastic arts in all aspects of life for the harmonious development of all human activities. It extended beside into practical politics, having elected as its honorary president the Minister for Reconstruction and Urban Development, Eugène Claudius-Petit.[16]

As time progressed, a distinction began to be made between 'cold abstraction', which was identified with geometric Concrete Art, and 'warm abstraction', which, as it moved towards the various kinds of Lyrical abstraction, reintroduced personality into art.[17] The former eventually fed into international movements building on technological aspects championed by the pioneers of Concrete Art, emerging as optical art, kinetic art and programmatic art.[18] The term Concrete also began to be extended to other disciplines than painting, including sculpture, photography and poetry. Justification for this was theorized in South America in the 1959 Neo-Concrete Manifesto, written by a group of artists in Rio de Janeiro who included Lygia Clark, Hélio Oiticica and Lygia Pape.[19]

International dimension

| City | Group | Year | Artists |

|---|---|---|---|

| Buenos Aires | Asociación Arte Concreto Invención | 1945 | |

| Buenos Aires | Movimento Madi | 1946 | Carmelo Arden Quin, Gyula Kosice, Rhod Rothfuss, Martín Blaszko, Diyi Laañ, Elizabeth Steiner, Juan Bay |

| Copenhagen | Linien II | 1947 | Ib Geertsen, Bamse Kragh-Jacobsen, Niels Macholm, Albert Mertz, Richard Winther, Helge Jacobsen |

| Milan | Movimento Arte Concreta (MAC) | 1948 | Atanasio Soldati, Gillo Dorfles, Bruno Munari, Gianni Monnet, Augusto Garau |

| Zagreb | Group Exat 51 | 1951 | Ivan Picelj, Vjenceslav Richter, Vlado Kristl, Aleksandar Srnec, Bernardo Bernardi |

| Paris | Group Espace | 1951 | |

| Montevideo | Grupo de Arte No Figurativo | 1952 | José Pedro Costigliolo, María Freire, Antonio Llorens |

| Rio de Janeiro | Grupo Frente | 1952 | Aluísio Carvão, Carlos Val, Décio Vieira, Ivan Serpa, João José da Silva Costa, Lygia Clark, Lygia Pape, Vicent Ibberson |

| São Paulo | Grupo Ruptura | 1952 | Waldemar Cordeiro, Geraldo de Barros, Luis Sacilotto, Lothar Charroux, Kazmer Fejer, Anatol Wladslaw, Leopoldo Haar |

| Ulm | Hochschule für Gestaltung | 1953 | |

| Cordoba | Equipo 57 | 1957 | |

| Havana | Los Diez Pintores Concretos | 1957-1961 | Pedro de Oraá, Loló Soldevilla, Sandú Darié, Pedro Carmelo Álvarez López, Wifredo Arrcay Ochandarena, Salvador Zacarías Corratgé Ferrera, Luis Darío Martínez Pedro, José María Mijares Fernández, Rafael Soriano López, and José Ángel Rosabal Fajardo |

| Padua | Gruppo N | 1959 | Alberto Biasi, Ennio Chiggio, Toni Costa, Edoardo Landi, Manfredo Massironi. |

| Milan | Gruppo T | 1959 | Giovanni Anceschi (1939), Davide Boriani (1936), Gabriele De Vecchi (1938), Gianni Colombo (1937-1993) e Grazia Varisco (1937) |

| Paris | Motus/GRAV | 1960 | Horacio Garcia Rossi, Julio Le Parc, Francois Morellet, Francisco Sobrino, Yvaral (Jean Pierre Vasarely), Joël Stein, and at the beginning also Hugo Demarco, Francisco García Miranda, Vera Molnàr, François Molnàr, Sergio Moyano Servanes, [20] |

| Cleveland | Anonima Group | 1960 | |

| Rome | Gruppo Uno | 1962 | Gastone Biggi, Nicola Carrino, Nato Frascà, Achille Pace, Pasquale Santoro, Giuseppe Uncini. Palma Bucarelli |

Museums

- Haus Konstruktiv museum of constructive and concrete art in Zurich, Switzerland

- Museum für Konkrete Kunst, Ingolstadt, Germany

- The Mondriaan House - Museum For Constructive And Concrete Art, Amersfoort, Netherlands

Bibliography

- Concrete Cuba: Cuban Geometric Abstraction from the 1950s, 2016, David Zwirner Books, ISBN 9781941701331 [21]

- Dempsey, Amy. Art in the Modern Era: A Guide to Styles, Schools & Movements , NY: Harry N. Abrams Inc., 2002

- Fabre, Gladys & Doris Wintgens Hötte : Van Doesburg & the international avant-garde. Constructing a new world, London, Tate Publishing, 2010.

- Fogelström, Lollo (ed.): Otto G. Carlsund: konstnär, kritiker och utställningsarrangör, Liljevalchs konsthall, 2007.

- Gottschaller, Pia; Le Blanc, Aleca (2017). Gottschaller, Pia; Le Blanc, Aleca; Gilbert, Zanna; Learner, Tom; Perchuk, Andrew (eds.). Making Art Concrete: Works from Argentina and Brazil in the Colección Patricia Phelps de Cisneros (Exhibition catalog). Los Angeles: Getty Conservation Institute and Getty Research Institute / Getty Publications. ISBN 978-1-606-06529-7. OCLC 982373712.

- Hartmann, Werner. Painting in the Twentieth Century , vol.1, second edition, London 1965

- Museum am Kulturspeicher (ed.): Concrete Art in Europe after 1945 - The Peter C. Ruppert Collection. Ostfildern-Ruit: Hatje Cantz, 2002. ISBN 3-7757-1191-0

- Pérez-Barreiro, Gabriel; Borja-Villel, Manuel (2013). Concrete Invention: Colección Patricia Phelps De Cisneros: Reflections on Geometric Abstraction from Latin America and Its Legacy (Exhibition catalog)

|format=requires|url=(help). Madrid: Museo Nacional Centro de Arte Reina Sofía/Turner. ISBN 978-8-415-42797-1. OCLC 828897697.

- Stiles, Kristine, “Geometric Abstraction” in Theories and Documents of Contemporary Art, Univ California 2012, pp.77-80

References

- Wintgens Hötte, Doris (2009) "Van Doesburg tackles the continent: passion, drive & calculation", in: Gladys Fabre & Doris Wintgens Hötte (red.): Van Doesburg & the International Avant-Garde: Constructing a New World, London, Tate Publishing, 2010, pp. 10-19.

- Jean Luc Daval, "Avant Garde Art 1914-1939", Skira, Geneva 1980, p.171

- Jean Hélion, "Art Concret 1930: Four Painters and a Magazine”, in Double Rhythm: Writings About Painting, Skyhorse Publishing 2014

- [fabstract Springer p.413-4]

- AC: Internationell utställning av postkubistisk konst, Stockholm, 1930, p.3

- Jean Luc Daval, "Avant Garde Art 1914-1939, Skira, Geneva 1980", p.171

- Hartmann p.285

- Hartmann p.340

- Hartmann p.341

- Monolith on the Water—Max Bill’s "Continuity" in a New Location; Deutsche Bank Art works

- Stiles

- Stiles

- Hartmann, p.340

- Ann Lee Morgan, Historical Dictionary of Contemporary Art, Rowman & Littlefield 2016

- Georges Folmer, "Le Salon des Réalités Nouvelles : pour et contre l’art concret", p.2

- Eve Roy, “La présence fondamentale de la plastique, L’exposition du Groupe Espace à Biot en 1954: un essai de synthèse des arts”, 2013

- Anna Moszynska, Abstract Art, Thames & Hudson, London 1990, p.120

- Alessandro Del Puppo, L'arte contemporanea: Il secondo novecento, Einaudi, 2013, table 3 page 238.

- Stiles

- Béatrice Gross, Stephen Hoban: François Morellet, Yale University Press, 2019, p. 59.

- "ERNESTO MENÉNDEZ-CONDE reviews "CONCRETE CUBA"". 2017-04-11.

External links

- Washington State University/Dr. Michael Delahoyde; commentary on Concrete art

- Monolith on the Water—Max Bill’s "Continuity" in a New Location; Deutsche Bank Art works

- Term defined by tate.org

- Kendall Art Center