Comet Lulin

Comet Lulin (official designation C/2007 N3 (Lulin), Traditional Chinese:鹿林彗星) is a non-periodic comet. It was discovered by Ye Quanzhi and Lin Chi-Sheng from Lulin Observatory.[1][2][7] It peaked in brightness and arrived at perigee for observers on Earth on February 24, 2009,[8] at magnitude +5,[2][9][10][11] and at 0.411 AU (61,500,000 km; 38,200,000 mi) from Earth.[8] The comet was near conjunction with Saturn on February 23, and outward first headed towards its aphelion, against the present position of background stars, in the direction of Regulus in the constellation of Leo, as noted on February 26 and 27, 2009.[2][7] It was expected to pass near Comet Cardinal on May 12, 2009.[12] The comet became visible to the naked eye from dark-sky sites around February 7.[13] It figured near the double star Zubenelgenubi on February 6, near Spica on February 15 and 16, near Gamma Virginis on February 19 and near the star cluster M44 on March 5 and 6. It also figured near the planetary nebula NGC 2392 on March 14, and near the double star Wasat around March 17.[14][15] According to NASA, Comet Lulin's green color comes from a combination of gases that make up its local atmosphere, primarily diatomic carbon, which appears as a green glow when illuminated by sunlight in the vacuum of space. When SWIFT observed comet Lulin on 28 January 2009, the comet was shedding nearly 800 US gallons (3,000 l) of water each second.[16] Comet Lulin was methanol-rich.

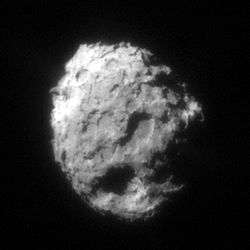

Comet Lulin as seen on January 31st (top) and February 4th of 2009. | |

| Discovery | |

|---|---|

| Discovered by | Ye Quanzhi, Lin Chi-Sheng[1][2] 0.41-m Ritchey–Chrétien (D35)[3] |

| Discovery date | July 11, 2007[1][2][3] |

| Alternative designations | Comet Lulin |

| Orbital characteristics A | |

| Epoch | December 6, 2008 (2454806.5)[4] |

| Aphelion | 2400 AU[5] |

| Perihelion | 1.2122 AU[4] |

| Semi-major axis | 1200 AU[5] |

| Eccentricity | 0.99998 (near parabolic)[4][6] |

| Orbital period | 42,000 yr[5] |

| Inclination | 178.37°[4] |

| Last perihelion | January 10, 2009[6] |

| Next perihelion | Unknown |

Discovery

The comet was first photographed by astronomer Lin Chi-Sheng (林啟生) with a 0.41-metre (16 in) telescope at the Lulin Observatory in Nantou, Taiwan on July 11, 2007. However, it was the 19-year-old Ye Quanzhi (葉泉志) from Sun Yat-sen University in China who identified the new object from three of the photographs taken by Lin.[17]

Initially, the object was thought to be a magnitude 18.9 asteroid, but images taken a week after the discovery with a larger 0.61-metre (24 in) telescope revealed the presence of a faint coma.[1][3][17]

The discovery occurred as part of the Lulin Sky Survey project to identify small objects in the Solar System, particularly Near-Earth Objects. The comet was named "Comet Lulin" after the observatory, and its official designation is Comet C/2007 N3.[18]

Orbit

Astronomer Brian Marsden of the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory calculated that Comet Lulin reached its perihelion on January 10, 2009, at a distance of 113 million miles (182 million kilometers) from the Sun.

The orbit of Comet Lulin is very nearly a parabola (parabolic trajectory), according to Marsden.[18] The comet had an epoch 2009 eccentricity of 0.999986,[6] and has an epoch 2010 eccentricity of 0.999998.[6] It is moving in a retrograde orbit at a very low inclination of just 1.6° from the ecliptic.[18]

Given the extreme orbital eccentricity of this object, different epochs can generate quite different heliocentric unperturbed two-body best-fit solutions to the aphelion distance (maximum distance) of this object. For objects at such high eccentricity, the sun's barycentric coordinates are more stable than heliocentric coordinates. Using JPL Horizons, the barycentric orbital elements for epoch 2014-Jan-01 generate a semi-major axis of about 1200 AU and a period of about 42,000 years.[5]

Disconnected tail

On February 4, 2009, a team of Italian astronomers witnessed "an intriguing phenomenon in Comet Lulin's tail". Team leader Ernesto Guido explains: "We photographed the comet using a remotely controlled telescope in New Mexico, and our images clearly showed a disconnection event. While we were looking, part of the comet's plasma tail was torn away."[19]

Guido and colleagues believe the event was caused by a magnetic disturbance in the solar wind hitting the comet. Magnetic mini-storms in comet tails have been observed before—most famously in 2007 when NASA's STEREO spacecraft watched a coronal mass ejection crash into Comet Encke. Encke lost its tail in dramatic fashion, much as Comet Lulin did on February 4.[19]

References

- Kronk, Gary W. "C/2007 N3 (Lulin)". cometography.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-06. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- Yoshida, Seiichi (December 31, 2008). "C/2007 N3 ( Lulin )". aerith.net. Retrieved 2009-01-02.

- "MPEC 2007-O05 : COMET C/2007 N3 (LULIN)". IAU Minor Planet Center. 2007-07-18. Retrieved 2011-07-05.

- "JPL Small-Body Database Browser: C/2007 N3 (Lulin)" (2010-03-11 last obs). Jet Propulsion Laboratory. Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- Horizons output. "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements for Comet Lulin (C/2007 N3)". Retrieved 2011-01-30. (Solution using the Solar System Barycenter. Select Ephemeris Type:Elements and Center:@0)

- "C/2007 N3 (Lulin) Orbital Elements". IAU Minor Planet Center. Archived from the original on 2016-01-26. Retrieved 2011-05-26.

- Dyer, Alan (2009). "Venus Kicks Off the Year of Astronomy (pg. 24-27)". In Dickinson, Terence (ed.). SkyNews: The Canadian Magazine of Astronomy & Stargazing. XIV, Issue 5 (January/February 2009 ed.). Yarker, Ontario: SkyNews Inc. p. 38.

- "JPL Close-Approach Data: C/2007 N3 (Lulin)" (2010-03-11 last obs). Retrieved 2010-03-23.

- Reinder J. Bouma and Edwin van Dijk. "C/2007 N3 (Lulin) magnitude estimates". Astrosite Groningen. Retrieved 2009-03-17.

- "Recent Comet Brightness Estimates". ICQ/CBAT/MPC. International Comet Quarterly. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- McRobert, Alan; Bryant, Greg (February 23, 2009). "Observing Highlights - Catch Comet Lulin at Its Best!". Sky & Telescope. SkyandTelescope.com. Archived from the original on January 10, 2009. Retrieved 2009-02-24.

- Dyer, Alan (2009). "The Top 10 Celestial Sights of 2009 (pg. 14)". In Dickinson, Terence (ed.). SkyNews: The Canadian Magazine of Astronomy & Stargazing. XIV, Issue 5 (January/February 2009 ed.). Yarker, Ontario: SkyNews Inc. p. 38.

- "Naked-Eye Comet". spaceweather.com. Retrieved 2009-02-07.

- "Path of Comet C/2007 N3 (Lulin), Mar. 1 - 20, 2009" (PDF). Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2009-03-24. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- McRobert, Alan M. "This Week's Sky at a Glance". Sky and Telescope. Archived from the original on 2009-03-18. Retrieved 2009-03-16.

- "NASA's Swift Spies Comet Lulin". NASA. 2009-02-20. Retrieved 2013-08-03.

- "IAUC 8857: C/2007 N3; S/2007 S 4". IAU Central Bureau for Astronomical Telegrams. 2007-07-18. Archived from the original on 2012-03-27. Retrieved 2011-06-03.

- "Newfound Comet Lulin to Grace Night Skies". space.com. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

- "DISCONNECTED TAIL". spaceweather.com. Retrieved 2009-02-09.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Comet Lulin. |

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Lulin and Saturn (February 27, 2009)

- NASA Astronomy Picture of the Day: Two Tails of Comet Lulin (February 25, 2009)

- 8 hour time sequence, from the live web cast

- Green Comet Approaches Earth, February 4, 2009

- C/2007 N3 (Lulin) Orbital elements

- Comet Lulin full-page finder charts

- Comet Lulin photo gallery

- Comet Lulin Comes Calling

- Sky Show Tonight: Green "Two-Tailed" Comet Arrives

- Time-Lapse Movie of Comet Lulin moving in the night sky, with stars steady

- Time-Lapse Movie of Comet Lulin moving in the night sky, with comet steady

- Drawing of Lulin's antitail structure

- Peat, Chris. "Comet C/2007 N3 Lulin". Heavens-Above GmbH. Heavens-Above.com. Retrieved 2009-04-26.

- Orbital simulation from JPL (Java) / Horizons Ephemeris