Cyberpunk derivatives

A number of cyberpunk derivatives have become recognized as distinct subgenres in speculative fiction.[1] Although these derivatives do not share cyberpunk's digitally-focused setting, they may display other qualities drawn from or analogous to cyberpunk: a world built on one particular technology that is extrapolated to a highly sophisticated level (this may even be a fantastical or anachronistic technology, akin to retro-futurism), a gritty transreal urban style, or a particular approach to social themes.

One of the most well-known of these subgenres, steampunk, has been defined as a "kind of technological fantasy",[1] and others in this category sometimes also incorporate aspects of science fantasy and historical fantasy.[2] Scholars have written of these subgenres' stylistic place in postmodern literature, and also their ambiguous interaction with the historical perspective of postcolonialism.[3]

American author Bruce Bethke coined the term "cyberpunk" in his 1980 short story of the same name, proposing it as a label for a new generation of punk teenagers inspired by the perceptions inherent to the Information Age.[4] The term was quickly appropriated as a label to be applied to the works of William Gibson, Bruce Sterling, John Shirley, Rudy Rucker, Michael Swanwick, Pat Cadigan, Lewis Shiner, Richard Kadrey, and others. Science fiction author Lawrence Person, in defining postcyberpunk, summarized the characteristics of cyberpunk thus:

Classic cyberpunk characters were marginalized, alienated loners who lived on the edge of society in generally dystopic futures where daily life was impacted by rapid technological change, an ubiquitous datasphere of computerized information, and invasive modification of the human body.[5]

The relevance of cyberpunk as a genre to punk subculture is debatable and further hampered by the lack of a defined cyberpunk subculture; where the small cyber movement shares themes with cyberpunk fiction and draws inspiration from punk and goth alike, cyberculture is much more popular though much less defined, encompassing virtual communities and cyberspace in general and typically embracing optimistic anticipations about the future. Cyberpunk is nonetheless regarded as a successful genre, as it ensnared many new readers and provided the sort of movement that postmodern literary critics found alluring. Furthermore, author David Brin argues, cyberpunk made science fiction more attractive and profitable for mainstream media and the visual arts in general.[6]

Futuristic derivatives

Biopunk

Biopunk emerged during the 1990s and focuses on the near-future unintended consequences of the biotechnology revolution following the discovery of recombinant DNA. Biopunk fiction typically describes the struggles of individuals or groups, often the product of human experimentation, against a backdrop of totalitarian governments or megacorporations which misuse biotechnologies as means of social control or profiteering. Unlike cyberpunk, it builds not on information technology but on biorobotics and synthetic biology. As in postcyberpunk however, individuals are usually modified and enhanced not with cyberware, but by genetic manipulation of their chromosomes.

Nanopunk

Nanopunk refers to an emerging subgenre of speculative science fiction still very much in its infancy in comparison to other genres like that of cyberpunk.[7] The genre is similar to biopunk, but describes a world in which the use of biotechnology is limited or prohibited, and only nanites and nanotechnology is in wide use (while in biopunk bio- and nanotechnologies often coexist). Currently the genre is more concerned with the artistic and physiological impact of nanotechnology, than of aspects of the technology itself. Still, one of the most prominent examples of nanopunk is the Crysis video game series; less famous examples are Generator Rex and Transcendence.[8]

Postcyberpunk

As new writers and artists began to experiment with cyberpunk ideas, new varieties of fiction emerged, sometimes addressing the criticisms leveled at the original cyberpunk stories. Lawrence Person wrote in an essay he posted to the Internet forum Slashdot in 1998:

The best of cyberpunk conveyed huge cognitive loads about the future by depicting (in best "show, don't tell" fashion) the interaction of its characters with the quotidian minutia of their environment. In the way they interacted with their clothes, their furniture, their decks and spex, cyberpunk characters told you more about the society they lived in than "classic" SF stories did through their interaction with robots and rocketships. Postcyberpunk uses the same immersive world-building technique, but features different characters, settings, and, most importantly, makes fundamentally different assumptions about the future. Far from being alienated loners, postcyberpunk characters are frequently integral members of society (i.e., they have jobs). They live in futures that are not necessarily dystopic (indeed, they are often suffused with an optimism that ranges from cautious to exuberant), but their everyday lives are still impacted by rapid technological change and an omnipresent computerized infrastructure.[5]

Person advocates using the term "postcyberpunk" for the strain of science fiction he describes. In this view, typical postcyberpunk stories explore themes related to a "world of accelerating technological innovation and ever-increasing complexity in ways relevant to our everyday lives" with a continued focus on social aspects within a post-third industrial-era society, such as of ubiquitous dataspheres and cybernetic augmentation of the human body. Unlike cyberpunk its works may portray a utopia or to blend elements of both extremes into a more mature (to cyberpunk) societal vision. Rafael Miranda Huereca states:

In this fictional world, the unison in the hive becomes a power mechanism which is executed in its capillary form, not from above the social body but from within. This mechanism as Foucault remarks is a form of power, which "reaches into the very grain of individuals, touches their bodies and inserts itself into their actions and attitudes, their discourses, learning processes and everyday lives". In postcyberpunk unitopia 'the capillary mechanism' that Foucault describes is literalized. Power touches the body through the genes, injects viruses to the veins, takes the forms of pills and constantly penetrates the body through its surveillance systems; collects samples of body substance, reads finger prints, even reads the 'prints' that are not visible, the ones which are coded in the genes. The body responds back to power, communicates with it; supplies the information that power requires and also receives its future conduct as a part of its daily routine. More importantly, power does not only control the body, but also designs, (re)produces, (re)creates it according to its own objectives. Thus, human body is re-formed as a result of the transformations of the relations between communication and power.[9]

The Daemon novels by Daniel Suarez could be considered postcyberpunk in that sense. In addition to themes of its ancestral genre postcyberpunk might also combine elements of nanopunk and biopunk.[10] Often named examples of postcyberpunk novels are Neal Stephenson's The Diamond Age and Bruce Sterling's Holy Fire. In television, Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex has been called "the most interesting, sustained postcyberpunk media work in existence".[11] In 2007, SF writers James Patrick Kelly and John Kessel published Rewired: The Post-Cyberpunk Anthology. Like all categories discerned within science fiction, the boundaries of postcyberpunk are likely to be fluid or ill defined.[12]

Cyber noir

Retrofuturistic derivatives

As a wider variety of writers began to work with cyberpunk concepts, new subgenres of science fiction emerged, playing off the cyberpunk label, and focusing on technology and its social effects in different ways. Many derivatives of cyberpunk are retro-futuristic, based either on the futuristic visions of past eras, especially from the first and second industrial revolution technological-eras, or more recent extrapolations or exaggerations of the actual technology of those eras.

Steampunk

The word "steampunk" was invented in 1987 as a jocular reference to some of the novels of Tim Powers, James P. Blaylock, and K. W. Jeter. When Gibson and Sterling entered the subgenre with their 1990 collaborative novel The Difference Engine the term was being used earnestly as well.[13] Alan Moore's and Kevin O'Neill's 1999 The League of Extraordinary Gentlemen historical fantasy comic book series (and the subsequent 2003 film adaptation) popularized the steampunk genre and helped propel it into mainstream fiction.[14]

The most immediate form of steampunk subculture is the community of fans surrounding the genre. Others move beyond this, attempting to adopt a "steampunk" aesthetic through fashion, home decor and even music. This movement may also be (perhaps more accurately) described as "Neo-Victorianism", which is the amalgamation of Victorian aesthetic principles with modern sensibilities and technologies. This characteristic is particularly evident in steampunk fashion which tends to synthesize punk, goth and rivet styles as filtered through the Victorian era. As an object style, however, steampunk adopts more distinct characteristics with various craftspersons modding modern-day devices into a pseudo-Victorian mechanical "steampunk" style.[15] The goal of such redesigns is to employ appropriate materials (such as polished brass, iron, and wood) with design elements and craftsmanship consistent with the Victorian era.[16]

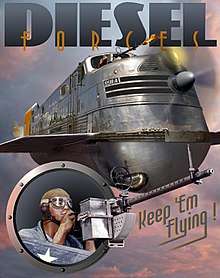

Dieselpunk

Dieselpunk is a genre and art style based on the aesthetics popular between World War I and the end of World War II. The style combines the artistic and genre influences of the period (including pulp magazines, serial films, film noir, art deco, and wartime pin-ups) with retro-futuristic technology[17][18] and postmodern sensibilities.[19] First coined in 2001 as a marketing term by game designer Lewis Pollak to describe his role-playing game Children of the Sun,[18][20] dieselpunk has grown to describe a distinct style of visual art, music, motion pictures, fiction, and engineering. Examples include the movies Iron Sky, Captain America: The First Avenger, The Rocketeer, K-20: Legend of the Mask, Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow and Dark City, and video games such as Crimson Skies, Greed Corp, Gatling Gears, BioShock and its sequel BioShock 2, The Legend of Korra, Skullgirls,[21] Wolfenstein, Iron Harvest, and Final Fantasy VII.[22][23][24]

Clockpunk

Clockpunk often portrays Renaissance-era science and technology based on pre-modern designs, in the vein of Mainspring by Jay Lake,[25] and Whitechapel Gods by S. M. Peters.[26] Examples of clockpunk include The Blazing World by Margaret Cavendish,[27] Astro-Knights Island in the nonlinear game Poptropica, the Clockwork Mansion level of Dishonored 2, the 2011 film version of The Three Musketeers, the TV series Da Vinci's Demons, as well as the videogames Thief: The Dark Project, Syberia and Assassins Creed 2. The book The Mechanical by Ian Tregillis is self-proclaimed clockpunk literature.[28]

For some, clockpunk is steampunk without steam. Atompunk, stonepunk, teslapunk, decopunk, nowpunk, are derivatives of clockpunk.[29]

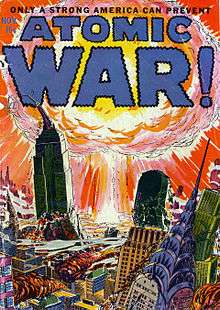

Atompunk

Atompunk relates to the pre-Third Industrial Revolution short twentieth century, specifically the period of 1945–1975, including mid-century modernism, the Atomic Age, Jet Age and Space Age, anti-communist and Red Scare paranoia in the United States, along with Neo-Soviet styling, underground cinema, Googie architecture, Sputnik and the Space Race, early Cold War espionage, superhero fiction and comic books and the rise of the U.S. military–industrial complex.[31][32] Its aesthetic tends toward Populuxe and Raygun Gothic, which describe a retro-futuristic vision of the world.[31] While most science fiction of the period carried an atompunk aesthetic, notable examples of atompunk in popular media include the Sean Connery-era of James Bond, television shows like The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, The Avengers, Doctor Who, The Green Hornet, The Man from U.N.C.L.E. and Archer, cartoons like Johnny Quest, Speed Racer, Dexter's Laboratory, The Powerpuff Girls and Venture Bros, comic-books like Justice League of America, Fantastic Four, The Incredible Hulk and Spider-Man, films like The Incredibles, Dr. Strangelove and X-Men: First Class, and video games like Destroy All Humans! and the Fallout series which received widespread distribution and critical acclaim.

Steelpunk

Steelpunk focuses on the technologies that had their heyday in the late 20th century. In a post describing Steelpunk on the SFFWorld website it is characterised as being "about hardware, not software, the real world not the virtual world, megatechnology not nanotechnology. The artefacts of Steelpunk aren't grown, printed or programmed, they're built. With rivets."[33] Examples given in the post include Mad Max, Terminator, Barb Wire, Iron Man and Snowpiercer. Other writers suggest Harry Harrison's Stainless Steel Rat series, the Heinlein juveniles and the film Sky Captain and the World of Tomorrow.

Rococopunk

Rococopunk is a whimsical punk derivative that thrusts punk attitude into the Rococo period, also known as late baroque. Although it is a fairly recent derivative,[34] it is a style that is visually similar to the New Romantic movement of the 1980s (particularly such groups as Adam and the Ants).[35] As one steampunk scholar[36] put it, "Imagine a world where the Rococo period never ended, and it had a lovechild with Sid Vicious.[37] Rococopunk has most recently been featured on The X Factor through the artist known as Prince Poppycock.[35] Fashion designer Vivienne Westwood, often known as "the Queen of Punk Fashion", also mixes Rococo with punk stylings.[38]

Decopunk

Decopunk is a recent subset of Dieselpunk, centered around the art deco and Streamline Moderne art styles, and based around the period between the 1920s and 1950s New York, Chicago, or Boston. In an interview[39] at CoyoteCon, steampunk author Sara M. Harvey made the distinctions "shinier than dieselpunk, more like decopunk", and "Dieselpunk is a gritty version of steampunk set in the 1920s–1950s. The big war eras, specifically. Decopunk is the sleek, shiny very art deco version; same time period, but everything is chrome!" Possibly the most notable examples of this are the first two BioShock games and Skullgirls, films like Dick Tracy, The Rocketeer, The Shadow, and Dark City, comic books like The Goon, and the cartoon Batman: The Animated Series which included neo-noir elements along with modern elements such as the use of VHS cassettes.

Stonepunk

Stonepunk refers to works set roughly during the Stone Age in which the characters utilize Neolithic Revolution–era technology constructed from materials more or less consistent with the time period, but possessing anachronistic complexity and function. The Flintstones franchise and its various spin offs, Roland Emmerich's 10,000 BC, the flashback scenes in Cro, and Dr. Stone fall under this category. Literary examples include Edgar Rice Burroughs' Back to the Stone Age and The Land that Time Forgot, and Jean M. Auel's "Earth’s Children" series, starting with The Clan of the Cave Bear.[40]

Other proposed science fiction derivatives

There have been a handful of divergent terms based on the general concepts of steampunk. These are typically considered unofficial and are often invented by readers, or by authors referring to their own works, often humorously.

A large number of terms have been used by the GURPS roleplaying game Steampunk to describe anachronistic technologies and settings, including stonepunk (Stone Age tech), bronzepunk (Bronze Age tech), ironpunk (Iron Age tech), candlepunk (Medieval and Renaissance tech), and transistorpunk (Atomic Age tech). These terms have seen very little use outside GURPS.[30]

Raypunk

Raypunk (or more commonly "Raygun gothic") is a distinctive (sub)genre which deals with scenarios, technologies, beings or environments, very different from everything that we know or what is possible here on Earth or by science. Covers space surrealism, parallel worlds, alien art, technological psychedelia, non-standard "science", alternative or distorted/twisted reality and so on.[41] Predecessor to atompunk with similar "cosmic" themes but mostly without explicit nuclear power or exactly described technology and with more archaic/schematic/artistic style, dark, obscure, cheesy, weird, mysterious, dreamy, hazy or etheric atmosphere (origins before 1880-1950), parallel to steampunk, dieselpunk and teslapunk.[42][43] While not originally designed as such, the original Star Trek series has an aesthetic very reminiscent of raypunk. The comic book series The Manhattan Projects, and the pre-WWII Buck Rogers and Flash Gordon comics and serials would be examples of raypunk.

Nowpunk

Nowpunk is a term invented by Bruce Sterling, which he applied to contemporary fiction set in the time period (particularly in the post-Cold War 1990s to the present) in which the fiction is being published, i.e. all contemporary fiction. Sterling used the term to describe his book The Zenith Angle, which follows the story of a hacker whose life is changed by the September 11, 2001 attacks.[44]

Cyberprep

Cyberprep is a term with a very similar meaning to postcyberpunk. The word is an amalgam of the prefix "cyber-", referring to cybernetics, and "preppy", reflecting its divergence from the punk elements of cyberpunk. A cyberprep world assumes that all the technological advancements of cyberpunk speculation have taken place but life is utopian rather than gritty and dangerous.[45] Since society is largely leisure-driven, advanced body modifications are used for sports, pleasure and self-improvement. An example would be Scott Westerfeld's Uglies series.

Solarpunk

Solarpunk is an movement, an subgenre, and an alternative to cyberpunk fiction that encourages optimistic envisioning of the future in light of present environmental concerns, such as climate change and pollution,[46] as well as social inequality.[47] Solarpunk fiction, which includes novels, short stories, and poetry, imagines futures that addresses environmental concerns with varying degrees of optimism. One example is News from Gardenia by actor-writer Robert Llewellyn.[48]

Other proposed fantastic fiction derivatives

Elfpunk

Elfpunk is subgenre of urban fantasy in which traditional mythological creatures such as faeries and elves are transplanted from rural folklore into modern urban settings and has been seen in books since the 1980s including works such as War of the Oaks by Emma Bull, Gossamer Axe by Gael Baudino, Artemis Fowl by Eoin Colfer, and The Iron Dragons' Daughter by Michael Swanwick. During the awards ceremony for the 2007 National Book Awards, judge Elizabeth Partridge expounded on the distinction between elfpunk and urban fantasy, citing fellow judge Scott Westerfeld's thoughts on the works of Holly Black who is considered "classic elfpunk—there's enough creatures already, and she's using them. Urban fantasy, though, can have some totally made-up f*cked-up [sic] creatures".[49] The 2020 Pixar animated film Onward is an example of an elfpunk film, set in a "suburban fantasy world" that combines modern and mythic elements.[50]

Mythpunk

Catherynne M. Valente uses the term "mythpunk" to describe a subgenre of mythic fiction which starts in folklore and myth and adds elements of postmodern literary techniques. As the -punk appendage implies,[51] mythpunk is subversive. In particular, it uses aspects of folklore to subvert or question dominant societal norms, often bringing in a feminist and/or multicultural approach. It confronts, instead of conforms to, societal norms.[52] Valente describes mythpunk as breaking "mythologies that defined a universe where women, queer folk, people of color, people who deviate from the norm were invisible or never existed" and then "piecing it back together to make something strange and different and wild".[51]

Typically, mythpunk narratives focus on transforming folkloric source material rather than retelling it, often through postmodern literary techniques such as non-linear storytelling, worldbuilding, confessional poetry, as well as modern linguistic and literary devices. The use of folklore is especially important because folklore is "often a battleground between subversive and conservative forces" and a medium for constructing new societal norms. Through postmodern literary techniques, mythpunk authors change the structures and traditions of folklore, "negotiating—and validating—different norms".[52]

Most works of mythpunk have been published by small presses, such as Strange Horizons,[53] because "anything playing out on the edge is going to have truck with the small presses at some point, because small presses take big risks".[51] Writers whose works would fall under the mythpunk label include Ekaterina Sedia, Theodora Goss, Neil Gaiman, Sonya Taaffe, Adam Christopher, and the anonymous author behind the pen name "B.L.A. and G.B. Gabbler". Valente's novel Deathless is a good example of mythpunk, drawing from classic Russian folklore to tell the tale of Koshchei the Deathless from a female perspective.[54]

References

- Bould, Mark (2005). "Cyberpunk". In Seed, David (ed.). A Companion to Science Fiction. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 217.

- Stableford, Brian (2005). "Alternative History". The A to Z of Fantasy Literature. Scarecrow Press. pp. 7–8.

- Smith, Eric D. (2012). "Third-World Punks, Or, Watch Out for the Worlds Behind You". Globalization, Utopia and Postcolonial Science Fiction: New Maps of Hope. Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bethke, Bruce (2000) [1997]. "The Etymology of "Cyberpunk"". Archived from the original on 2008-01-08. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Person, Lawrence (1998). "Notes Toward a Postcyberpunk Manifesto". Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Brin, David (2003). "The Matrix: Tomorrow May Be Different". Archived from the original on 2008-03-22. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- "Nanopunk definition". Azonano.com. 2007-06-12. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- Hawkes-Reed, J. (2009). "The Guerilla Infrastructure HOWTO". In Colin Harvey (ed.). Future Bristol. Swimming Kangaroo. ISBN 1-934041-93-9. Archived from the original on 2010-12-27. Retrieved 2010-12-17.

- Altintaş, Aciye Gülengül (February 2006). Postcyberpunk Unitopia: A Comparative Study of Cyberpunk and Postcyberpunk (PDF) (MA thesis). Istanbul Bilgi University Institute of Social Sciences. Retrieved 13 January 2017.

- Huereca, Rafael Miranda. "The evolution of cyberpunk into postcyberpunk: The role of cognitive cyberspaces, wetware networks and nanotechnology in science fiction" (PDF): 324. Retrieved 19 May 2015. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Person, Lawrence (2006-01-15). "Ghost in the Shell: Stand Alone Complex". Locus Online. Retrieved 2008-02-07.

- Person, Lawrence (1998). "Notes Towards a Postcyberpunk Manifesto". The Cyberpunk Project. Archived from the original on 2009-08-23. Retrieved 2007-06-18.

- Berry, Michael (1987-06-25). "Wacko Victorian Fantasy Follows 'Cyberpunk' Mold". The San Francisco Chronicle. Wordspy. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Damon Poeter (2008-07-06). "Steampunk's subculture revealed". The San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved 2008-07-15.

- Braiker, Brian (2007-10-31). "Steampunking Technology; A subculture hand-tools today's gadgets with Victorian style". Newsweek. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Bebergal, Peter (2007-08-26). "The age of steampunk". The Boston Globe. Retrieved 2008-04-02.

- Aja Romano (2013-10-08). "Dieselpunk for beginners: Welcome to a world where the '40s never ended". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- 'Piecraft'; Ottens, Nick (July 2008), "Discovering Dieselpunk" (PDF), The Gatehouse Gazette (Issue 1): 3, retrieved 2010-05-23

- Larry Amyett (October 24, 2013). "What's in a Name?". The Gatehouse. Archived from the original on June 26, 2015. Retrieved June 25, 2015.

- Pollak Jr., Lewis B. (2001). "Misguided Games, Inc. is pleased to announce that Children of the Sun has shipped from the printer". Archived from the original on January 19, 2007.

- Krzysztof, Janicz (2008). ""Chronologia dieselpunku" (in Polish)".

- sinisterporpoise (March 30, 2010). Hartman, Michael (ed.). "Top 10 Steampunk and Dieselpunk Games for the PC". Bright Hub. Archived from the original on June 5, 2010. Retrieved 2010-05-25.

- Romano, Aja (8 October 2013). "Dieselpunk for beginners: Welcome to a world where the '40s never ended". The Daily Dot. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Boyes, Philip (8 February 2020). "Hot Air and High Winds: A Love Letter to the Fantasy Airship". Eurogamer. Retrieved 18 April 2020.

- Sawicki, Steve (2007-06-12). "Mainspring by Jay Lake". Sfrevu.com. Retrieved 2008-08-01.

- Johnson, Andrea (2008-02-05). "Whitechapel Gods by S.M. Peters". Sfrevu.com. Retrieved 2011-03-07.

- Centuries Before 'Arrival': The Original Science Fiction - The Atlantic

- Lauren Sarner (4 January 2016). "Ian Tregillis Is Creating His Own 'Clockpunk' Genre". Inverse.com. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- "Clockpunk and the Perils of Reimagining the Past". Ingmaralbizu.com. 30 April 2018. Retrieved 18 November 2019.

- Stoddard, William H., GURPS Steampunk (2000)

- Sterling, Bruce (2008-12-03). "Here Comes 'Atompunk.' And It's Dutch. So there". Wired. Archived from the original on 2013-12-03. Retrieved 2010-07-04.

- Doctorow, Cory (December 3, 2008). "Atompunk: fetishizing the atomic age". Boing Boing. Retrieved 2015-06-25.

- "Is Steelpunk the new Steampunk? Does Steelpunk even exist?". SFFWorld. 2017-10-29. Retrieved 2018-08-04.

- "Rococopunk is not only sillier than Steampunk, it's also more punk". io9. Gizmodo. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Rococo Punk "Less Steampunk, more cake"". Welcome to Steampunk. welcometosteampunk.com. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- ""AnachroCon: A Behind-the-Scenes Look"–A Con Report by Austin Sirkin". Beyond Victoriana. beyondvictoriana.com. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

Austin Sirkin is a graduate student at Georgia State University studying 19th Century Science Fiction. He uses his critical background to also study steampunk and speaks about it at conventions and conferences around the country.

- "The Alternate History of Steampunk: Rococopunk". WONDER HOW TO: STEAMPUNK R&D. wonderhowto.com. Retrieved June 9, 2018.

- "Vivienne Westwood: Rococo Eccentricity & Modern Marie Antoinettes". Jezebel: FASHION. jezebel.com. Retrieved June 10, 2018.

- "Rayguns! Steampunk Fiction". Interview transcript. 17 May 2010. Archived from the original on 21 May 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2015.

- "All Sorts of Punk". Die Wachen. Archived from the original on 2012-02-08. Retrieved 13 June 2012.

- Thomson, Gemma. "Cyberpunk and Raypunk". RaygunGoth. WordPress. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- "Raypunk - definition". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 2018-10-19.

- Konstantinou, Lee. "Hopepunk can't fix our broken science fiction". Slate.com. Slate. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- Laura Lambert; Hilary W. Poole; Chris Woodford; Christos J. P. Moschovitis (2005). The Internet: A Historical Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. p. 224. ISBN 1-85109-659-0.

- Blankenship, Loyd. (1995) GURPS Cyberpunk: High-Tech Low-Life Rolepaying Sourcebook. Steve Jackson Games. ISBN 1-55634-168-7

- Boffa, Adam. "At the Very Least We Know the End of the World Will Have a Bright Side". Longreads. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- Jacobs, Suzanne. "This sci-fi enthusiast wants to make "solarpunk" happen". Grist. Retrieved 7 May 2019.

- https://www.amazon.co.uk/News-Gardenia-Robert-Llewellyn/dp/1908717122/ref=tmm_hrd_title_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

- Hogan, Ron (2007-10-15). "2007 National Book Awards". Archived from the original on 2008-10-07. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- "Onward". Pixar Animation Studios. Disney/Pixar. Retrieved 21 March 2020.

- "Mythpunk: An Interview with Catherynne M. Valente". 2011-01-24. Archived from the original on 2015-02-19. Retrieved 2015-02-19.

- Valente, Catherynne M. (January 24, 2011). "Mythpunk: An Interview with Catherynne M. Valente, by JoSelle Vanderhooft". jenngrunigen.com. Strange Horizons. Archived from the original on September 10, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- Harrison, Niall (January 31, 2011). "amimythpunkornot.com". Strange Horizons. Strange Horizons. Archived from the original on September 15, 2015. Retrieved October 21, 2015.

- McAra, Catriona (January 2012). "Valente's Mythpunk" (PDF). Scotland Russia Forum Review. Archived from the original (PDF) on December 8, 2015. Retrieved November 22, 2015.

External links

- "Make Way for Plaguepunk, Bronzepunk, and Stonepunk", Annallee Newitz, Wired, March 15, 2007.

- "Punk Punk" index of Cyberpunk derivatives on TV Tropes