Climate change and indigenous peoples

Climate change disproportionately impacts indigenous people around the world, especially in terms of their health, environments, and communities. Indigenous people found in Africa, the Arctic, Asia, Australia, the Caribbean, Latin America, North America and the Pacific have strategies and traditional knowledge to adapt to climate change. These knowledge systems can be beneficial for their own adaptation to climate change as well as applicable to non-indigenous people.

The majority of the world’s biological, ecological, and cultural diversity is located within Indigenous territories. There are over 370 million indigenous peoples [1] found across 90+ countries.[2] Approximately 22% of the planet's land is comprised of indigenous territories, varying slightly depending on how indigeneity and land usage is determined.[3] Indigenous people have the important role of the main knowledge keepers within their communities, including knowledge relating to the maintenance of social-ecological systems.[4] The United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous People recognizes that Indigenous people have specific knowledge, traditional practices, and cultural customs that can contribute to the proper and sustainable management of ecological resources.[5]

Indigenous Peoples have a myriad of experiences with the effects of climate change because of the varying geographical areas they inhabit across the globe and because of the differences in cultures and livelihoods. Indigenous Peoples have a wide variety of experiences that Western science is beginning to include in its research of climate change and its potential solutions. The concepts of ancestral knowledge and traditional practices are increasingly respected and considered in Western scientific research.[6]

Disproportionate impact of climate change on Indigenous Peoples

Reports show that millions of people across the world will have to relocate due to rising seas, floods, droughts, and storms.[7] While this will affect people all over the world, the impact will disproportionately affect Indigenous people.[7]

Indigenous people will be more impacted by climate change for multiple reasons. Many Indigenous cultures and lifestyles are linked directly to the environment,[8] therefore the health of the environment in which they live is extremely important for their physical and spiritual wellbeing. Changing climates that alter the environment will have greater effects on people who depend on the environment directly, both spiritually and physically.[9] While beliefs that Indigenous people will suffer more because of their deep connection to the land are true in many cases,[10] the increased negative effects of climate change are also directly related to oppression and poverty caused by colonialism.[11]

Indigenous peoples and communities globally have experienced a series of traumatic invasions that have had long-lasting and disastrous outcomes. Massacres, genocidal policies, disease pandemics, forced removal and relocation, Indian boarding school assimilation policies, and prohibition of spiritual and cultural practices have produced a history of ethnic and cultural genocide.[12]

Indigenous communities across the globe generally have economic disadvantages that are not are prevalent in non-indigenous communities due to the long term oppression they have experienced. These disadvantages such as lower education levels, higher rates of poverty and unemployment add to their vulnerability to climate change.[9]

Many studies suggests that Indigenous peoples have strong ability to adapt when it comes to the environmental changes caused by climate change, and there are many instances in which Indigenous people are adapting.[9] Their adaptability lies in the traditional knowledge within their cultures, which through "traumatic invasions" have been lost.[9][12] The loss of traditional knowledge and oppression that Indigenous people face pose a greater threat than the changing of the environment itself.

Africa

Climate change in Africa will lead to food insecurity, displacement of Indigenous persons, as well as increased famine, drought, and floods.[13] In some regions of Africa, like Malawi, climate change can also lead to landslides, hailstorms, and mudslides.[14] Pressure from climate change on Africa is amplified because disaster management infrastructure is nonexistent or severely inadequate throughout the continent.[13] Furthermore, the impact of climate change in Africa falls disproportionately on Indigenous people because they have limitations on their migration and mobility, are more negatively affected by decreased biodiversity, and have their agricultural land disproportionately degraded by climate change.[13] In Malawi, there has been a decrease in yield per unit hectare due to prolonged droughts and inadequate rainfall.[14]

The northernmost and southernmost countries within the continent of Africa are considered subtropical. Drought is one of the most significant threats posed by climate change to subtropical regions.[15] Drought leads to subsequent issues regarding the agricultural sector which has significant effects on the livelihoods of populations within those areas.[15] Pastoralists throughout the continent have coped with the aridity of the land through the adoption of a nomadic lifestyle to find different sources of water for their livestock.[16]

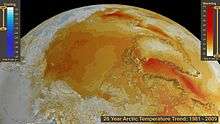

Arctic

Climate change is having the most dramatic impact on the Arctic with a temperature increase twice the magnitude of the increase in the rest of the world.[17] This is resulting in significant sinking of the ice in the Arctic Sea. Satellite images of the ice show that it currently has the smallest area in recorded history.[13] If left unchecked, climate change in the Arctic will lead to a faster rise in sea level, more frequent and increasingly intense storms and winds, further decreases in the extent of sea ice, and increased erosion due to higher waves.[18]

This consequence of climate change will have a number of effects on the Inuit people in a variety of ways. Eroding coasts and thinning ice have changed the migration patterns of the numerous animal species such as killer whales, marine polar bears, caribou, and seals.[19] Seals are one of the numerous animals hunted by the Inuit people upon which they depend. The seals are just one of the various species whose population is diminishing due to melting of ice sheets on which they are dependent for raising their young on. Additionally, the rapid melting of the sea ice creates a more hazardous and unpredictable terrain to hunt in, posing a new risk within their subsistence economy.[20]

Simultaneously, increased temperatures and melting permafrost will make it harder for Inuit people to freeze and store food in their traditional way. Furthermore, climate change will bring new bacteria and other micro-organisms to the region, which will bring yet unknown effects to the Peoples of the region.[13]

One example of the Indigenous groups acting in response to climate change in the Arctic was the Alaska Inter-Tribal Council taking action regarding the decline in the polar bear population that was directly linked to the decline in ice sheets for them to live on.[19] The Alaska Natives rely on polar bears and cohabit with them and through their Indigenous knowledge have contributed to the co-management with the U.S. federal government to increasing and improving conservation efforts regarding the popular megafauna.[21][22]

Asia

Indigenous people in Asia are plagued with a wide variety of problems due to climate change, including but not limited to, lengthy droughts, floods, irregular seasonal cycles, typhoons and cyclones with unprecedented strength, and highly unpredictable weather.[13] This has led to worsening food and water security, which in turn factor into an increase in water-borne diseases, heat strokes, and malnutrition.[13] Indigenous lifestyles in Asia have been completely uprooted and disrupted due to the above factors, but also due to the increased expansion of mono-culture plantations, hydroelectric dams, and the extraction of uranium on their lands and territories prior to their free and informed consent.[13]

Australia

Indigenous People of Australia and Climate Change Background

Aboriginal Australians and Traditional Knowledge

.jpg)

Indigenous people have always responded and adapted to climate change, including these indigenous people of Australia.[23] Aboriginal Australian people have existed in Australia for thousands of years. Due to this continual habitation, Aboriginal Australians have observed and adapted to climatic and environmental changes for millennium which uniquely positions them to be able to respond to current climate changes.[23][24] Though these communities have shifted and changed their practices overtime, traditional ecological knowledge exists that can benefit local and indigenous communities today.[24] This knowledge is part of traditional cultural and spiritual practices within these indigenous communities. The practices are directly tied to the unique relationship between Aboriginal Australians and their ecological landscapes. This relationship results in a socio-ecological system of balance between humans and nature [25] Indigenous communities in Australia have specific generational traditional knowledge about weather patterns, environmental changes and climatic changes.[26][27][28] These communities have adapted to climate change in the past and have knowledge that Western, non-Indigenous people may be able to utilize to adapt to climate change currently and in the future.[29]

Despite having little input in terms of the creation current international and local policies to adapting to climate change, Indigenous people have pushed back on this reality, by trying to be active members in the conversation surrounding climate change including at international meetings.[30] Specifically, Indigenous people of Australia have traditional knowledge to adapt to increased pressures of global environmental change.[26]

Though some of this traditional knowledge was not utilized and conceivable lost with the introduction of white settlers in the 18th century but recently communities have begun to revitalize these traditional practices.[31] This traditional knowledge includes language, cultural, spiritual practices, land management.[27][24]

Indigenous People of Australia Community Responses to Climate Change

Indigenous knowledge has been passed down through the generations with the practice of oral tradition.[32] Given the historical relationship between the land and the people and the larger ecosystem Aboriginal Australians choose to stay and adapt in similar ways to their ancestors before them.[26] Aboriginal Australians have observed short and long term environmental changes are keenly aware of weather and climate changes.[27] Recently, elders have begun to be utilized by indigenous and non-indigenous communities to understand traditional knowledge related to land management.[33] This includes seasonal knowledge means indigenous knowledge pertaining to weather, seasonal cycles of plants and animals, and land and landscape management.[24][25] The seasonal knowledge allows indigenous communities to combat environmental changes and may result in healthier social-ecological systems.[25] Much of traditional landscape and land management includes keeping the diversity of floral and fauna as traditional foodways.[24] Ecological calendars is one traditional framework used by Aboriginal Australian communities. These ecological calendars are way for indigenous communities to organize and communicate traditional ecological knowledge.[24] The ecological calendars includes seasonal weather cycles related to biological, cultural, and spiritual ways of life.[24]

Some of these changes include a rise in sea levels, getting hotter and for a longer period of time, and more severe cyclones during the cyclone season.[34] Climate issues include wild fires, heatwaves, floods, cyclones, rising sea-levels, rising temperatures, and erosion.[35][23][32] The communities most effected by climate changes are those in the North where Aboriginal Australian people make up 30% of the population.[34] Aboriginal Australian communities located in the coastal north are the most disadvantaged due to social and economic issues and their reliance on traditional land for food, culture, and health. This has begged the question for many community members in these regions, should they move away from this area or remain present.[34]

Many Aboriginal Australians live in rural and remote agricultural areas across Australia, especially in the Northern and Southern areas of the continent.[32][35] There are a variety of different climate impacts on different Aboriginal communities which includes cyclones in the Northern region and flooding in Central Australia which negatively impacts cultural sites and therefore the relationship between indigenous people and the places that hold their traditional knowledge.[23]

Climate Change Threats and Adaptation

Vulnerability

This vulnerability comes from remote location where indigenous groups live, lower socio-economic status, and reliance of natural systems for economic needs.[35]

.jpg)

Many of the economic, political, and social-ecological issues present in indigenous communities are long term effects from colonialism and the continued marginalization of these communities. These issues are aggravated by climate change and environmental changes in their respective regions.[32][33] Indigenous people are seen as particularly vulnerable to climate change because they already live in poverty, poor housing, poor educational and health services, and other socio-political factors place them at risk for climate change impacts.[23] Indigenous people have been portrayed as victims and as vulnerable populations for many years by the media.[32][33] Aboriginal Australians believe that they have always been able to adapt to climate changes in their geographic areas.[23]

Many communities have argued for more community input into strategies and ways to adapt to climate issues instead of top down approaches to combating issues surrounding environmental change.[26][34] This includes self-determination and agency when deciding how to respond to climate change including proactive actions.[34] Indigenous people have also commented on the need to maintain their physical and mental well being in order to adapt to climate change which can be helped through the kinship relationships between community members and the land they occupy.[26]

In Australia, Aboriginal people have argued that in order for the government to combat climate change, their voices must be included in policy making and governance over traditional land.[33][32] Much of the government and institutional policies related to climate change and environmental issues in Australia has been done so through a top down approach.[25] Indigenous communities have stated that this limits and ignored Aboriginal Australian voices and approaches.[33][25] Due to traditional knowledge held by these communities and elders within those communities, traditional ecological knowledge and frameworks are necessary to combat these and a variety of different environmental issues.[32][33]

Heat and Drought

Fires and droughts in Australia, including the Northern regions, occur mostly in savannas because of current environmental changes in the region. The majority of the fire prone areas in the savanna region are owned by Aboriginal Australian communities, the traditional stewards of the land.[31] Aboriginal Australians have traditional landscape management methods including burning and clearing the savanna areas which are the most susceptible to fires.[31] Traditional landscape management declined in the 19th century as western landscape management took over.[31] Today, traditional landscape management has been revitalized by Aboriginal Australians, including elders. This traditional landscape practices include the use of clearing and burning to get rid of old growth. Though the way in which indigenous communities in this region manage the landscape has been banned, Aboriginal Australian communities who use these traditional methods actual help in reducing greenhouse gas emissions.[31]

Impact of Climate Change on Health

Increased temperatures, wildfires, and drought are major issues in regard to the health of Aboriginal Australian communities. Heat poses a major risk to elderly members of communities in the North.[28] This includes issues such as heat stroke and heat exhaustion.[28] Many of the rural indigenous communities have faced thermal stress and increased issues surrounding access to water resources and ecological landscapes. This impacts the relationship between Aboriginal Australians and biodiversity, as well as impacts social and cultural aspects of society.[28]

Aboriginal Australians who live in isolated and remote traditional territories are more sensitive than non-indigenous Australians to changes that effect the ecosystems they are a part of. This is in large part due to the connection that exists between their health (including physical and mental), the health of their land, and the continued practice of traditional cultural customs.[35] Aboriginal Australians have a unique and important relationship with the traditional land of their ancestors. Because of this connection, the dangerous consequences of climate change in Australia has resulted in a decline in health including mental health among an already vulnerable population.[28][36] In order to combat health disparities among these populations, community based projects and culturally relevant mental and physical health programs are necessary and should include community members when running these programs.[36]

Caribbean

Impacts of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples

The impacts of climate change are taking a disproportionate toll on Indigenous peoples,[37] when Indigenous peoples contribute least to climate change. The main effect of climate change in the Caribbean region is the increased occurrence of extreme weather events. There have been an influx of flash floods, tsunamis, earthquakes, extreme winds, and landslides in the region.[13] These events have led to wide-ranging infrastructural damage to both public and private property for all. For example, Hurricane Ivan inflicted damage totalling 135% of Grenada's GDP to Grenada, setting the country back an estimated ten years in development.[13] The effects of these events are most strongly felt, however, by Indigenous persons, who have been forced to move to the most extreme areas of the country due to the lasting effects that colonialism had on the region.[13] In these extreme regions, extreme weather events are even more pronounced, leading to crop and livestock devastation.[13] Also, in the Caribbean, people have reported erosion of beaches, a reduction in vegetation, a noticeable rise in sea-level, and rivers that are drying up.[38]

Adaptation Strategies

Among changing agricultural practices, it is imperative for Indigenous peoples and inhabitants of these regions to integrate disaster plans, national sustainable development goals and environmental conservation into daily lives.[39]

As indigenous lands are constantly under attack, from governments to industries, it is imperative for Indigenous peoples to partner with groups such as the Rainforest Alliance to fight and protest for Indigenous rights.[40]

Latin America

.jpg)

Indigenous Peoples Background

Although some cultures thrive in urban settings like Mexico City or Quito, Indigenous peoples in Latin America populate most of the rural poor areas in countries such as Ecuador, Brazil, Peru and Paraguay.[41] Indigenous people consist of 40 million of the Latin American-Caribbean populations.[42] This makes these populations extremely susceptible to threats of climate change due to socioeconomic, geographic, and political factors. Formal education is limited in these areas which caps contributions of skills to the market economy. Mostly living in the Amazon Rainforest, there are more than 600 ethnographic-linguistic identities living in the Latin American region.[42] This distinction of cultures provides different languages, world-views, and practices that contribute to Indigenous livelihoods.

Impacts of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples

Humans have impacted climate change through land use, extractive practices, and resource use. Not only have humans exacerbated climate change, our actions are threatening the livelihoods of Indigenous peoples in targeted and susceptible areas. Specifically, extractive industries in the Amazon and the Amazonian Basin are threatening the livelihood of Indigenous persons by land use and exacerbating climate change. These extractive policies were originally implemented without the consent of indigenous people are now being implemented without respect to the rights of indigenous people, specifically in the case of REDD. Not only do deforestation and fragmentation of forests negatively affect the areas and livelihoods of inhabitants, but contributes to the release of more carbon into the atmosphere, as the trees provided as carbon sinks, which exacerbates climate change even more.[43] Thus, deforestation has and will continue to have disproportionate effects on Indigenous people in Latin American tropical forests, including the displacement of these communities from their native lands.[44] Also, in the Amazon Basin where fish are a main resource, precipitation and flooding greatly impact fish reproduction drastically. Likewise, this inconsistency in precipitation and flooding has affected, and decreased the reproduction of fish and turtles in the Amazon River.[42] Furthermore, climate change has altered the patterns of migratory birds and changed the start and end times of wet and dry seasons, further increasing the disorientation of the daily lives of Indigenous people in Latin America.

As most of the contributions and the roles of combating climate change, the rights and resources of Indigenous peoples often go unrecognized, these communities face disproportionate and the most negative repercussions of climate change and from conservation programs.[39] Due to the close relationship with nature and Indigenous peoples, they are among the first to face the repercussions of climate change and at a large devastating degree.[39]

Gender Inequality

Indigenous peoples suffer disproportionately from the impacts of climate change, women even more so. Discrimination and some customary laws hinder political involvement, making numbers for Indigenous women extremely low.[41] Although Indigenous women's involvement still lag behind, countries such as Bolivia, Ecuador, Guatemala, Mexico, Nicaragua, and Peru have improved their political participation of Indigenous peoples.[41] Furthermore, women often face strenuous physical labor. To reduce harm, improve health of humans and the environment, a nongovernmental organization in Brazil introduced an eco-stove that eliminates the need for heavy fuelwood for energy and to cook. This has empowered Indigenous women in Brazil and surrounding areas as around 53,000 people have the opportunity to live healthier and easier lives.[45]

Adaptation Strategies

Due to Indigenous peoples' extensive knowledge and ability to predict and interpret weather patterns and conditions, these populations are vital to adaptation and survival of posed climate threats. From hundreds of years experimenting with nature and developing inherently sustainable cultural strategies has allowed Indigenous peoples to pass on their knowledge to future generations. This has made Indigenous peoples crucial to understanding the relationship between nature, people, and conserving the environment.[42] In Latin America and the Caribbean, Indigenous peoples are restructuring and changing agricultural practices in adaptation to climate changes. They are also moving and relocating agriculture activities from drought inflicted areas to areas with more suitable, wetter areas.[43] It is imperative for the Americas and the Caribbean to continue pursuing conservation of the environment as 65% of indigenous land has not been developed intensely.[44]

Policy and Global Action

After the Zapatista movement in Mexico in the Mid-1990s, Indigenous issues were recognized internationally and the start of progress for Indigenous political involvement and recognition. Bearing the best political representation, Bolivia, Ecuador, and Venezuela have the largest political representation, Mexico being recognized as having the largest gap in proportion to representation and population.[46] International treaties and goals like the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, the Paris Agreement, and the Addis Ababa Action Agenda have recognized the rights of Indigenous peoples.[47]

Women play a crucial role in combating climate change especially in Indigenous culture, and it is imperative to recognize strong leadership and their successes. Despite the threats of climate change, Indigenous women have risen up and pushed for sustainable solutions at local and global scales.[47]

North America

Environmental changes due to climate change that have and will continue to have effects on Indigenous Peoples in North America include temperature increases, precipitation changes, decreased glacier and snow cover, rising sea level, increased floods, droughts and extreme weather.[13] Food and water insecurity,[9] limited access to traditional foods and locations, and increased exposure to infectious diseases are all human dimension impacts that will most likely follow the environmental changes stated above.[48]

One in four Native Americans face food insecurity. North American tribes, such as the Inuit, rely on subsistence activities like hunting, fishing, and gathering. 15-22% of the diet in some tribal communities is from a variety of traditional foods. These activities are important to the survival of tribal culture, and to the collective self-determination of a tribe. Indigenous North American diets consist of staple foods like wild rice, shellfish, beans, moose, deer, berries, caribou, walrus, corn, squash, fish, and seal[49]. The effects of climate change—including changes in the quality and availability of freshwater, the changing migratory patterns of staple species, and the increased rarity of native plant species—have made it increasingly difficult for tribes to subsist on their traditional diets and participate in their culturally important activities. The traditional diets of indigenous North Americans also provide essential nutrients[50]. In the absence of these essential staples—and often because the populations reside in “food deserts” and are subject to poverty[51]—Native Americans living on reservations are subject to higher levels of detrimental diet-related diseases such as diabetes, obesity, and heart disease. In some Native American counties in the U.S., 20% of children aged 2-5 are obese[52].

The Indigenous populations in the United States and Canada are communities that are disproportionately vulnerable to the effects of climate change due to socioeconomic disadvantages.[53][54] These environmental changes will have implications on the lifestyle of Indigenous groups which include, but are not limited to, Alaska Natives, Inuit, Dene, and Gwich'in people.[9] There are higher rates of poverty, lower levels of access to education, to housing, and to employment opportunities in indigenous communities than there are in non-indigenous communities within North America.[53] These conditions increase indigenous communities' vulnerability and sensitivity to climate change.[48] These socioeconomic disadvantages not only increase their vulnerability and in some cases exposure, they also limit indigenous groups' capacity to cope with and recover from the harmful effects climate change brings. Some of the solutions proposed for combating climate change in North America like coal pollution mitigation, and GMO foods actually violate the rights of Indigenous Peoples and ignore what is in their best interest in favor of sustaining economic prosperity in the region.[13] Additionally, many tribal communities have already faced the need to relocate or protect against climate change (such as sea level rise), but there is a general lack of funds and dedicated government-supported programs to assist tribal communities in protecting themselves from climate change and resettlement, which can result in the further erosion of indigenous cultures and communities.[55] Furthermore, the loss of biodiversity in the region has severely limited the ability of Native people to adapt to changes in their environment. Such uncertainties and changes in livelihood and even culture, alongside the destruction of culturally significant ecosystems and species, can negatively affect people’s mental health and “sense of place.”[56][57] Additionally, increases in temperature threatens cultural practices. Many indigenous ceremonies involve going for days without food or water, which can become health and even life threatening in increasingly hot temperatures.[58]

An important topic to consider when looking at the intersection of climate change and Indigenous populations is having an indigenous framework and understanding indigenous knowledge. Because of the direct effect climate change has on the livelihoods of many indigenous peoples and their connection to the land and nature, these communities have developed various indigenous knowledge systems. Indigenous knowledge refers to the collective knowledge that has been accumulated and evolved across multiple generations concerning people's relationship to the environment[59]. These knowledge systems are becoming increasingly important within the conversations surrounding climate change because of the long timeline of ecological observations and regional ecological understanding. However, there are dangers which come with sharing them. Traditional knowledge is often a part of an indigenous population's spiritual identity, and misuse of it can lead to disrespect and exploitation of their culture, thus some may be hesitant to share their knowledge[60]. However, an example of the ways indigenous knowledge has been used effectively to understand climate change is the monitoring of the Arctic by Alaska Natives. Their knowledge has been used to monitor changes in animal behavior and weather patterns, as well to develop ways of adapting in a shifting environment.[61]

In reaction to the environmental changes within North American tribal communities, movements of Indigenous activism have organized and risen to protest against the injustices enforced upon them. A notable and recent example of Indigenous activism revolves around the #NoDAPL movement. “On April 1st, tribal citizens of the Standing Rock Lakota Nation, and other Lakota, Nakota, and Dakota citizens founded a spirit camp along the proposed route of the Dakota Access Pipeline”[62] to object against the installment of an oil pipeline through indigenous land. Another example would be in Northwestern Ontario, where indigenous peoples of Grassy Narrows First Nation have protested against the clear-cut logging in their territory.[63] Fishing tribes in Washington State have protested against overfishing and habitat destruction.[64] Indigenous environmental activism against effects of climate change and forces that facilitate ongoing damaging effects to tribal land, aims to correct their vulnerability and disadvantaged status, while also contributing to the broader discussion of tribal sovereignty. In efforts to promote acknowledgement of Indigenous tribes in accordance with Indigenous environmental activism, Indigenous scientists and organizations, such as the American Indian Science and Engineering Society, have called out the importance of incorporating indigenous sciences into efforts toward sustainability[65], as indigenous sciences offers understanding of the natural world and human’s relation to it unlike Western sciences.

Pacific

The region is characterized by low elevation and insular coastlines, making it severely susceptible to the increased sea-level and erosion effects of climate change.[66] Entire islands have sunk in the Pacific region due to climate change, dislocating and killing Indigenous persons.[13] Furthermore, the region suffers from continually increasing frequency and severity of cyclones, inundation and intensified tides, and decreased biodiversity due to the destruction of coral reefs and sea ecosystems.[13] This decrease in biodiversity is coupled with a decreased populations of the fish and other sea life the Indigenous people of the region rely upon for food.[13] Indigenous people of the region are also losing many of its food sources, such as sugarcane, yams, taro, and bananas, to climate change as well as seeing a decrease in the amount of drinkable water made available from rainfall.[13]

Many Pacific Island nations have a heavy economic reliance upon the tourism industry. Indigenous people are not outside of the economic conditions of a nation, therefore they are impacted by the fluctuations of tourism and how that has been impacted by climate change. Pacific coral reefs are a large tourist attraction and with the acidification and warming of the ocean due to climate change, the coral reefs that many tourists want to see are being bleached leading to a decline in the industry's prosperity.[66]

According to Rebecca Tsosie, a professor known for her work in indigenous peoples’ human rights, the effects of the global climate change are especially visible in Pacific region of the world. She cites the Indigenous peoples’ strong and deeply interconnected relationship with their environment. This close relationship brings about a greater need for the Indigenous populations to adapt quickly to the effects of climate change because of how reliant they are upon the environment around them.[19]

Climate Action of Indigenous Peoples

Indigenous Peoples are working to prevent and combat the effects of climate change in a variety of ways, including through climate activism. Some examples of Indigenous climate activists include Autumn Peltier, from Wiikwemkoong First Nation on Manitoulin Island in northern Ontario and Nina Gualinga from the Kichwa community of Sarayaku in the Ecuadorian Amazon.[67][68]

Autumn Peltier, from Wiikwemkoong First Nation on Manitoulin Island in northern Ontario, has been a driving force in the fight to protect water in Canada’s Indigenous communities. Peltier is the chief water commissioner for Anishinabek Nation, which advocates for 40 member First Nations in Ontario. At just 15 years old, Peltier is rallying for action to protect Indigenous waters and has become a part of the climate action movement.[67]

Nina Gualinga has spent most of her life working to protect the nature and communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon. At 18, she represented Indigenous youth before the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, helping to win a landmark case against the Ecuadorian government for allowing oil drilling on Indigenous lands. She now advocates on the international stage for Indigenous rights and a fossil-fuel-free economy. Gualinga recently received the WWF International President’s Youth Award, which acknowledges outstanding achievements by conservationists under the age of 30.[68]

Indigenous communities are also working to combat the impacts of climate change on their communities through community initiatives.[69] For example, Inuit community members of Rigolet, Nunastavit in Labrador are working to combat feelings of cultural disconnect through organizing the teaching of traditional skills in community classes, allowing people to feel more connected with their culture and each other. Additionally, Rigolet community members worked with researchers from Guelph University, to develop an app that allows community members to share their findings regarding the safety of local sea ice, as a way to reduce the anxiety surrounding the uncertainty of environmental conditions. Community members have identified these resources as valuable tools in coping with the ecological grief they feel as a result of climate change.

Additionally, Indigenous communities and groups are working with governmental programs to adapt to the impacts climate change is having on their communities.[70] An example of such a governmental program is the Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program (CCHAP) within the First Nations Inuit Health Branch of Indigenous Services Canada. The Selkirk First Nation worked with the CCHAP to undertake a project that focused on the relationship between the land, water and the people who rely on the fish camps for food security and to continue cultural practices that support the mental, physical, emotional and spiritual well-being of their people. The Confederacy of Mainland Mi’kmaq’s Mi’kmaw Conservation Group in Nova Scotia also worked with the CCHAP on a project involving conducting climate-related research, engaging community members, developing needs assessments and reporting on the state of climate change-related emergency plans. The Indigenous Climate Action (ICA) is also an organization that is the only Indigenous climate justice organization in Canada.[71] They implement "tools, education, and capacity needed to ensure Indigenous knowledge is a driving force in climate solutions." Specifically, they held many demonstrations helping Teck withdraw from the Frontier tar sands project.[71]

The benefits of Indigenous participation in climate change research and governance

Historically, Indigenous persons have not been included in conversations about climate change and frameworks for them to participate in research have not existed. For example, Indigenous people in the Ecuadorian rainforest who had suffered a sharp decrease in biodiversity and an increase of greenhouse gas emissions due to the deforestation of the Amazon were not included in the 2005 Reducing emissions from deforestation and forest degradation (REDD+) project.[72] This is especially difficult for Indigenous people because many can perceive changes in their local climate, but struggle with giving reasons for their observed change.[14]

Indigenous Knowledge

Critics of the program insist that their participation is necessary not only because they believe that it is necessary for social justice reasons but also because Indigenous groups are better at protecting their forests than national parks.[72] This place-based knowledge rooted in local cultures, Indigenous knowledge (IK), is useful in determining impacts of climate change, especially at the local level where scientific models often fail.[73] Furthermore, IK plays a crucial part in the rolling-out of new environmental programs because these programs have a higher participation rate and are more effective when Indigenous Peoples have a say in how the programs themselves are shaped.[73] Within IK there is a subset of knowledge referred to as Traditional Ecological Knowledge (TEK). TEK is the knowledge that Indigenous Peoples have accumulated through the passing of lessons and experiences from generation to generation.[74] TEK is specifically knowledge about the group's relationship with and their classifications of other living beings and the environment around them.

Climate Change and Governance

By extension, governance, especially climate governance, would benefit from an institutional linking to IK because it would hypothetically lead to increased food security.[73] Such a linkage would also foster a shared sense of responsibility for the usage of the environment's natural resources in a way that is in line with sustainable development as a whole, but especially with the UN's Sustainable Development Goals.[73] In addition, taking governance issues to Indigenous people, those who are most exposed and disproportionately vulnerable to climate issues, would build community resilience and increase local sustainability, which would in turn lead to positive ramifications at higher levels.[73] It is theorized that harnessing the knowledge of Indigenous persons on the local level is the most effective way of moving towards global sustainability.[73] Indigenous communities in Northern Australia have specific generational traditional knowledge about weather patterns and climatic changes. These communities have adapted to climate change in the past and have knowledge that Western, non-Indigenous people can utilize to adapt to climate change in the future.[4] More recently, an increasing number of climate scientists and Indigenous activists advocate for the inclusion of TEK into research regarding climate change policy and adaptation efforts for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities.[75][76]

The Intergovernmental Panel for Climate Change (IPCC) emphasized their support for the inclusion of IK in their Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5 °C saying:

There is medium evidence and high agreement that indigenous knowledge is critical for adaptation, underpinning adaptive capacity through the diversity of indigenous agro-ecological and forest management systems, collective social memory, repository of accumulated experience and social networks...Many scholars argue that recognition of indigenous rights, governance systems and laws is central to adaptation, mitigation and sustainable development.[77]

References

- Etchart, Linda (2017-08-22). "The role of indigenous peoples in combating climate change". Palgrave Communications. 3 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.85. ISSN 2055-1045.

- "Indigenous Peoples". World Bank. Retrieved 2020-02-23.

- Sobrevila, Claudia (2008). The role of indigenous peoples in biodiversity conservation: the natural but often forgotten partners. Washington, DC: World Bank. p. 5.

- Green, D.; Raygorodetsky, G. (2010-05-01). "Indigenous knowledge of a changing climate". Climatic Change. 100 (2): 239–242. Bibcode:2010ClCh..100..239G. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9804-y. ISSN 1573-1480.

- Nations, United. "United Nations Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples" (PDF).

- Mazzocchi, Fulvio (May 2006). "Western science and traditional knowledge: Despite their variations, different forms of knowledge can learn from each other". EMBO Reports. 7 (5): 463–466. doi:10.1038/sj.embor.7400693. ISSN 1469-221X. PMC 1479546. PMID 16670675.

- Kapua'ala Sproat, D. "An Indigenous People’s Right to Environmental Self-Determination: Native Hawaiians and the Struggle Against Climate Change Devastation." Stanford Environmental Law Journal 35, no. 2.

- Green, Donna; King, Ursula; Morrison, Joe (January 2009). "Disproportionate burdens: the multidimensional impacts of climate change on the health of Indigenous Australians". Medical Journal of Australia. 190 (1): 4–5. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2009.tb02250.x. ISSN 0025-729X.

- Ford, James D. (2012-05-17). "Indigenous Health and Climate Change". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (7): 1260–1266. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3477984. PMID 22594718.

- Levy, Barry S.; Patz, Jonathan A. (2015-11-27). "Climate Change, Human Rights, and Social Justice". Annals of Global Health. 81 (3): 310–322. doi:10.1016/j.aogh.2015.08.008. ISSN 2214-9996. PMID 26615065.

- Whyte, Kyle (2017-03-01). "Indigenous Climate Change Studies: Indigenizing Futures, Decolonizing the Anthropocene". English Language Notes. 55 (1–2): 153–162. doi:10.1215/00138282-55.1-2.153. ISSN 0013-8282.

- Coté, Charlotte (2016-07-15). ""Indigenizing" Food Sovereignty. Revitalizing Indigenous Food Practices and Ecological Knowledges in Canada and the United States". Humanities. 5 (3): 57. doi:10.3390/h5030057. ISSN 2076-0787.

- "Report of the Indigenous Peoples' Global Summit on Climate Change." Proceedings of Indigenous People's Global Summit on Climate Change, Alaska, Anchorage.

- Nkomwa, Emmanuel Charles, Miriam Kalanda Joshua, Cosmo Ngongondo, Maurice Monjerezi, and Felistus Chipungu. "Assessing Indigenous Knowledge Systems and Climate Change Adaptation Strategies in Agriculture: A Case Study of Chagaka Village, Chikhwawa, Southern Malawi." Physics and Chemistry of the Earth, Parts A/B/C 67-69 (2014): 164-72. doi:10.1016/j.pce.2013.10.002.

- Ishaya, S.; Abahe, I. B. (November 2008). "Indigenous people's perception on climate change and adaptation strategies in Jema'a local government area of Kaduna State, Nigeria". Journal of Geography and Regional Planning. 1: 138–143.

- Hansungule, Michelo; Jegede, Ademola Oluborode (2014). "The Impact of Climate Change on Indigenous Peoples' Land Tenure and Use: The Case for a Regional Policy in Africa". International Journal on Minority and Group Rights. 21: 256–292. doi:10.1163/15718115-02102004.

- McClintok, James; Ducklow, Hugh; Fraser, William (August 2008). "Ecological Responses to Climate Change on the Antarctic Peninsula: The Peninsula is an icy world that's warming faster than anywhere else on Earth, threatening a rich but delicate biological community". American Scientist. 96 (4): 302–310. doi:10.1511/2008.73.3844. JSTOR 27859177.

- Overeem, Irina; Anderson, Robert S.; Wobus, Cameron W.; Clow, Gary D.; Urban, Frank E.; Matell, Nora (2011). "Sea ice loss enhances wave action at the Arctic coast". Geophysical Research Letters. 38 (17): n/a. Bibcode:2011GeoRL..3817503O. doi:10.1029/2011GL048681. ISSN 1944-8007.

- Tsosie, Rebecca (2007). "Indigenous People and Environmental Justice: The Impact of Climate Change". University of Colorado Law Review. 78: 1625–1678.

- Forbes, Donald (2011), "State of the Arctic coast 2010: scientific review and outlook" (PDF), AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, Institute of Coastal Research, 2010: GC54A–07, Bibcode:2010AGUFMGC54A..07R

- Kanayurak, Nicole (2016). "A Case Study of Polar Bear Co-Management in Alaska" (PDF).

- Forbes, Donald (2011), "State of the Arctic coast 2010: scientific review and outlook" (PDF), AGU Fall Meeting Abstracts, Institute of Coastal Research, 2010: GC54A–07, Bibcode:2010AGUFMGC54A..07R

- Nursey-Bray, Melissa; Palmer, R.; Smith, T. F.; Rist, P. (2019-05-04). "Old ways for new days: Australian Indigenous peoples and climate change". Local Environment. 24 (5): 473–486. doi:10.1080/13549839.2019.1590325. ISSN 1354-9839.

- Prober, Suzanne; O'Connor, Michael; Walsh, Fiona (2011-05-17). "Australian Aboriginal Peoples' Seasonal Knowledge: a Potential Basis for Shared Understanding in Environmental Management". Ecology and Society. 16 (2). doi:10.5751/ES-04023-160212. ISSN 1708-3087.

- Leonard, Sonia; Parsons, Meg; Olawsky, Knut; Kofod, Frances (2013-06-01). "The role of culture and traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation: Insights from East Kimberley, Australia". Global Environmental Change. 23 (3): 623–632. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2013.02.012. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Petheram, L.; Zander, K. K.; Campbell, B. M.; High, C.; Stacey, N. (2010-10-01). "'Strange changes': Indigenous perspectives of climate change and adaptation in NE Arnhem Land (Australia)". Global Environmental Change. 20th Anniversary Special Issue. 20 (4): 681–692. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2010.05.002. ISSN 0959-3780.

- Green, Donna; Billy, Jack; Tapim, Alo (2010-05-01). "Indigenous Australians' knowledge of weather and climate". Climatic Change. 100 (2): 337–354. Bibcode:2010ClCh..100..337G. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9803-z. ISSN 1573-1480.

- Horton, Graeme; Hanna, Liz; Kelly, Brian (2010). "Drought, drying and climate change: Emerging health issues for ageing Australians in rural areas". Australasian Journal on Ageing. 29 (1): 2–7. doi:10.1111/j.1741-6612.2010.00424.x. ISSN 1741-6612. PMID 20398079.

- Green, D.; Raygorodetsky, G. (2010-05-01). "Indigenous knowledge of a changing climate". Climatic Change. 100 (2): 239–242. Bibcode:2010ClCh..100..239G. doi:10.1007/s10584-010-9804-y. ISSN 1573-1480.

- Etchart, Linda (2017-08-22). "The role of indigenous peoples in combating climate change". Palgrave Communications. 3 (1). doi:10.1057/palcomms.2017.85. ISSN 2055-1045.

- Russell-Smith, Jeremy; Cook, Garry D.; Cooke, Peter M.; Edwards, Andrew C.; Lendrum, Mitchell; Meyer, CP (Mick); Whitehead, Peter J. (2013). "Managing fire regimes in north Australian savannas: applying Aboriginal approaches to contemporary global problems". Frontiers in Ecology and the Environment. 11 (s1): e55–e63. doi:10.1890/120251. ISSN 1540-9309.

- Ford, James D. (July 2012). "Indigenous Health and Climate Change". American Journal of Public Health. 102 (7): 1260–1266. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3477984. PMID 22594718.

- Belfer, Ella; Ford, James D.; Maillet, Michelle (2017). "Representation of Indigenous peoples in climate change reporting". Climatic Change. 145 (1): 57–70. Bibcode:2017ClCh..145...57B. doi:10.1007/s10584-017-2076-z. ISSN 0165-0009. PMC 6560471. PMID 31258222.

- Zander, Kerstin K.; Petheram, Lisa; Garnett, Stephen T. (2013-06-01). "Stay or leave? Potential climate change adaptation strategies among Aboriginal people in coastal communities in northern Australia". Natural Hazards. 67 (2): 591–609. doi:10.1007/s11069-013-0591-4. ISSN 1573-0840.

- Green, Donna (November 2006). "Climate Change and Health: Impacts on Remote Indigenous Communities in Northern Australia". S2CID 131620899. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Berry, Helen L.; Butler, James R. A.; Burgess, C. Paul; King, Ursula G.; Tsey, Komla; Cadet-James, Yvonne L.; Rigby, C. Wayne; Raphael, Beverley (2010-08-06). "Mind, body, spirit: co-benefits for mental health from climate change adaptation and caring for country in remote Aboriginal Australian communities". New South Wales Public Health Bulletin. 21 (6): 139–145. doi:10.1071/NB10030. ISSN 1834-8610. PMID 20637171.

- "Commonality among unique indigenous communities: an introduction to climate change and its impacts on indigenous peoples" (PDF).

- Macpherson, Cheryl; Akpinar-Elci, Muge (January 2013). "Impacts of Climate Change on Caribbean Life". American Journal of Public Health. 103 (1): e6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.301095. ISSN 0090-0036. PMC 3518358. PMID 23153166.

- "Conservation and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples".

- "The World's Best Forest Guardians: Indigenous Peoples". Rainforest Alliance. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Indigenous peoples". UNDP in Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- Kronik, Jakob; Verner, Dorte (2010). "Indigenous Peoples and Climate Change in Latin America and the Caribbean". Directions in Development - Environment and Sustainable Development. doi:10.1596/978-0-8213-8237-0. hdl:10986/2472. ISBN 978-0-8213-8237-0.

- "Climate Change and Indigenous peoples" (PDF).

- "EGM: Conservation and the Rights of Indigenous Peoples 23–25 January 2019 Nairobi, Kenya | United Nations For Indigenous Peoples". www.un.org. Retrieved 2020-02-24.

- "Brazil eco-stoves empower indigenous women". UNDP in Latin America and the Caribbean. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- Hoffay, Mercedes; August 31, Sofía Rivas /; English, 2016Click to read this article in SpanishClick to read this article in (2016-08-31). "The indigenous in Latin America: 45 million with little voice". Global Americans. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- August 09; Herrera, 2017 Carolina. "Indigenous Women: Defending the Environment in Latin America". NRDC. Retrieved 2020-03-23.

- Ford, James D. (2012). "Indigenous health and climate change". Am J Public Health. 102 (7): 1260–6. doi:10.2105/AJPH.2012.300752. PMC 3477984. PMID 22594718.

- Kathryn, Norton-Smith. "Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Synthesis of Current Impacts and Experiences" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture. USDA. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- "One in 4 Native Americans is Food Insecure". Move for Hunger. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Jernigan, Valarie (25 October 2016). "Food Insecurity among American Indians and Alaska Natives: A National Profile using the Current Population Survey–Food Security Supplement". Journal of Hunger & Environmental Nutrition. 12 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1080/19320248.2016.1227750. PMC 5422031. PMID 28491205.

- "Combating Food Insecurity on Native American Reservations" (PDF). Native Partnership. Northern Plains Reservation Aid. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Norton-Smith, Kathryn (October 2016). "Climate Change and Indigenous Peoples: A Synthesis of Current Impacts and Experiences" (PDF). U.S. Forest Service.

- Turner, Nancy J.; Clifton, Helen (2009). "It's so different today: Climate change and indigenous lifeways in British Columbia, Canada". Global Environmental Change. 19 (2): 180–190. doi:10.1016/j.gloenvcha.2009.01.005.

- Maldonado, Julie (9 April 2013). "The impact of climate change on tribal communities in the US: displacement, relocation, and human rights". Climate Change. 120 (3): 601–614. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0799-z. PMC 3831579. PMID 24265512.

- Voggesser, Garrit (29 March 2013). "Cultural impacts to tribes from climate change influences on forests". Climate Change. 120 (3): 615–626. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0733-4.

- Ellis, Neville (February 2017). "Climate change threats to family farmers' sense of place and mental wellbeing: A case study from the Western Australian Wheatbelt". Social Science & Medicine. 175: 161–168. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.01.009. PMID 28092757.

- Doyle, John (22 June 2013). "Exploring effects of climate change on Northern Plains American Indian health". Climate Change. 120 (3): 643–655. doi:10.1007/s10584-013-0799-z. PMC 3831579. PMID 24265512.

- Nakashima, Douglas (2018). Indigenous Knowledge for Climate Change Assessment and Adaptation. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 9781316481066.

- Williams, Terry; Hardison, Preston (2014). Culture, law, risk and governance: contexts of traditional knowledge in climate change adaptation (First ed.). Springer International Publishing. pp. 23–36. ISBN 978-3-319-05266-3.

- Swanson, Greta. "Traditional Ecological Knowledge in the United States: Contributions to Climate Adaptation and Natural Resource Management (Part I)". Environmental Law Institute. Retrieved 8 May 2020.

- Streeby, Shelley (2018). Imagining the Future of Climate Change : World-Making Through Science Fiction and Activism. University of California Press. pp. 34–68. ISBN 9780520294455.

- Willow, Anna J. (2009). "Clear-Cutting and Colonialism: The Ethnopolitical Dynamics of Indigenous Environmental Activism in Northwestern Ontario". Ethnohistory. Duke University Press. 56 (1): 35–67. doi:10.1215/00141801-2008-035.

- Cantzler, Julia; Huynh, Megan (2015). "Native American Environmental Justice as Decolonization". American Behavioral Science. Sage Journals. 60 (2): 203–223. doi:10.1177/0002764215607578.

- Streeby, Shelley (2018). magining the Future of Climate Change : World-Making Through Science Fiction and Activism. University of California Press. pp. 34–68. ISBN 9780520294455.

- UNEP 2014. Emerging issues for Small Island Developing States. Results of the UNEP Foresight Process. United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP), Nairobi, Kenya.

- "'It's time for action': Indigenous water activist Autumn Peltier to speak at UN forum | National Post". 26 September 2019.

- "Activist Nina Gualinga on protecting the Amazon". World Wildlife Fund.

- Fabian, Sabrina (May 27, 2017). "Trapped 'like a caged animal': Climate change taking toll on mental health of Inuit". CBC- Radio Canada.

- Richards, Gabrielle; Frehs, Jim; Myers, Erin; Bibber, Marilyn Van (2019). "CommentaryThe Climate Change and Health Adaptation Program:Indigenous climate leaders' championing adaptation efforts". Health Promotion and Chronic Disease Prevention in Canada : Research, Policy and Practice. 39 (4): 127–130. doi:10.24095/hpcdp.39.4.03. ISSN 2368-738X. PMC 6553577. PMID 31021063.

- "Home | Indigenous Climate Action". indigenousaction.

- Krause, Torsten, Wain Collen, and Kimberly A. Nicholas. "Evaluating Safeguards in a Conservation Incentive Program: Participation, Consent, and Benefit Sharing in Indigenous Communities of the Ecuadorian Amazon." Ecology and Society 18, no. 4 (2013). doi:10.5751/es-05733-180401.

- Chanza, Nelson, and Anton De Wit. "Enhancing Climate Governance through Indigenous Knowledge: Case in Sustainability Science." South African Journal of Science 112, no. 3 (March/April 2016).

- Alexander, Clarence; Bynum, Nora; Johnson, Elizabeth; King, Ursula; Mustonen, Tero; Neofotis, Peter; Oettlé, Noel; Rosenzweig, Cynthia; Sakakibara, Chie; Shadrin, Vyacheslav; Vicarelli, Marta (2011-06-01). "Linking Indigenous and Scientific Knowledge of Climate Change". BioScience. 61 (6): 477–484. doi:10.1525/bio.2011.61.6.10. ISSN 0006-3568.

- Vinyeta, Kirsten; Lynn, Kathy (2013). "Exploring the role of traditional ecological knowledge in climate change initiatives" (PDF). General Technical Report. United States Department of Agriculture.

- IPCC (2018). "Summary for Policymakers". Global Warming of 1.5°C. An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.

- IPCC (2018). "Chapter 4: Strengthening and implementing the global response" (PDF). An IPCC Special Report on the Impacts of Global Warming of 1.5°C Above Pre-industrial Levels and Related Global Greenhouse Gas Emission Pathways, in the Context of Strengthening the Global Response to the Threat of Climate Change, Sustainable Development, and Efforts to Eradicate Poverty.