Clan Fraser of Lovat

Clan Fraser of Lovat (Scottish Gaelic: Friseal [ˈkʰl̪ˠãũn̪ˠ ˈfɾʲiʃəl̪ˠ]; French: Clan Fraiser) is a Highland Scottish clan. The Clan Fraser of Lovat has been strongly associated with Inverness and the surrounding area since the Clan's founder gained lands there in the 13th century, but Lovat is in fact a junior branch of the Clan Fraser who were based in the Aberdeenshire area. Both the Clan Fraser and the Clan Fraser of Lovat have their own separate clan chiefs who are recognized by the Lord Lyon King of Arms under Scottish law. The Clan Fraser of Lovat in Inverness-shire has historically dominated local politics and been active in every major military conflict involving Scotland. It has also played a considerable role in most major political turmoils. "Fraser" remains the most prominent family name within the Inverness area.

| Clan Fraser of Lovat | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Clann Friseal[1] | |||

Crest: A buck's head, erased, Or, armed, Argent | |||

| Motto | Je suis prest (I am ready)[1] | ||

| War cry | "A Mhor-fhaiche" or "Caisteal Dhuni" | ||

| Profile | |||

| Region | Highland | ||

| District | Inverness-shire | ||

| Plant badge | French fraise (Strawberry)[1] | ||

| Animal | Stag | ||

| Pipe music | Lovat's March[1] | ||

| Chief | |||

| |||

| The Rt. Hon. Simon Fraser | |||

| The 18th Lord Lovat[1] (Mac Shimidh or Mac Shimidh Mòr[2][3]) | |||

| Seat | Beaufort, near Inverness and Strichen House, Aberdeenshire. | ||

| Historic seat | Beaufort Castle (Castle Dounie)[4] | ||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

| |||

The Clan's current chief is Simon Fraser, the 16th Lord Lovat, and 26th Chief of Clan Fraser.

History

Origins of the surname

The exact origins of the surname "Fraser" can not be determined with any great certainty.[5] Traditionally it is thought to have originated in France, but the Oxford Dictionary of Family Names (2016) notes there is no place name in France corresponding with the earliest spellings of the name – "de Fresel", "de Friselle", and "de Freseliere" – and suggests the possibility it represents a Gaelic name "corrupted beyond recognition by Anglo-Norman scribes".[6]

The first definite record of the name in Scotland occurs in the mid-12th century as "de Fresel", "de Friselle", and "de Freseliere",[5] and appears to be an Angevin name. The French surname "Frézelière" or "de la Frézelière" or "Frézeau de la Frézelière", exists in France to this day,[7] and is still concentrated in the area of Anjou.[5] It also corresponds with the Scottish version in its spelling. Belief in the name's Angevin origin has also been firmly held by the Frasers themselves. Whilst in exile in France, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat "entered into a formal league of amity" and "declared an alliance" with the French Marquis de la Frézelière and claimed common origin from the "les seigneurs de la Frézelière".[8] The first annual gathering of the Clan Fraser in Canada in 1894 also recalls this connection.[9]

There is other evidence of an ancient connection with Anjou. An 18th century document La Dictionnaire de la Noblesse states that a Simon Frezel was born to the knightly Frezel family from Anjou and, sometime after the year 1030, established himself in Scotland. It also states that Simon Frezel's descendants multiplied and eventually became known as Frasers.[10] This would also explain the prevalence of the name Simon throughout clan history, as all Frasers (by descent) would have the knight Simon Frezel as a distant but common ancestor.

There are other suggested links with France, but these are more in the realm of myth than history:

- The surname "Frysel"[11] (vowels were at the time often interchanged) is recorded on the Battle Abbey Roll – supposedly a list of William the Conqueror's companions, preserved at Battle Abbey, on the site of his great victory over Harold.[12] However, the authenticity of the manuscript is seriously doubted.[13]

- Another story claims the name derives from a Frenchman called "Pierre Fraser, Seigneur de Troile", who came to Scotland in the reign of Charlemagne to form an alliance with the mythical King Achaius.[14] Pierre's son then became thane of the Isle of Man in 814.[14]

- One tradition suggests that the surname is derived from the French words fraise, meaning strawberry (the fruit), and fraisiers, strawberry plants.[15] There is a fabled account of the Fraser coat of arms which asserts that during the reign of Charles the Simple of France, a nobleman from Bourbon named Julius de Berry entertained the King with a dish of fine strawberries.[14] De Berry was then later knighted, with the knight taking strawberry flowers as his Arms and changing his name from "de Berry" to "Fraiseux" or "Frezeliere".[14] His direct descendants were to become the lords of Neidpath Castle, then known as Oliver.[16] This origin has been disputed,[17] and seen as a classic example of canting heraldry, where heraldic symbols are derived from a pun on similar-sounding surname: (strawberry flowers – fraises).[18][19]

Early Frasers

Around the reign of William the Lion (r.1165–1214), there was a mass of "Norman" immigration into Scotland. Thomas Grey, a 14th-century English knight, listed several "Norman" families which took up land during William's reign.[20] Among those listed, the families of Moubray, Ramsay, Laundells, Valognes, Boys and Fraser are certainly or probably introduced under King William.[20]

The earliest written record of Frasers in Scotland is in 1160, when a Simon Fraser held lands in East Lothian at Keith. In that year, he made the gift of a church to the Tironensian monks at Kelso Abbey.[15] The Frasers moved into Tweeddale in the 12th and 13th centuries and from there into the counties of Stirling, Angus, Inverness and Aberdeen.[16]

Wars of Scottish Independence

During the Scottish Wars of Independence, Sir Simon Fraser, known as "the Patriot", fought first with the Red Comyn, and later with Sir William Wallace and Robert the Bruce.[16] Sir Simon is celebrated for having defeated the English at the Battle of Roslin in 1303, with just 8,000 men under his command.[16] At the Battle of Methven in 1306, Sir Simon Fraser led troops along with Bruce, and saved the King's life in three separate instances. Simon was allegedly awarded the 3 Crowns which now appear in the Lovat Arms for these three acts of bravery. He was however captured by the English and executed with great cruelty by Edward I of England in 1306, in the same barbaric fashion as Wallace.[16] At the Battle of Bannockburn in 1314, Sir Simon's cousin, Sir Alexander Fraser of Touchfraser and Cowie, was much more fortunate. He fought at Bannockburn, married Bruce's sister, and became Chamberlain of Scotland. The Frasers of Philorth who are chiefs of the senior Clan Fraser trace their lineage from this Alexander.[16] Alexander's younger brother, another Sir Simon Fraser, was the ancestor of the chiefs of the Clan Fraser of Lovat.[21] This Simon Fraser was killed at the Battle of Halidon Hill in 1333, along with his younger brothers Andrew and James.[16]

15th and 16th century clan conflicts

As most all Highlanders, the Frasers have been involved in countless instances of Clan warfare, particularly against the Macdonalds.[15] Two Gaelic war cries of the Frasers have been generally recognized. The first, "Caisteal Dhuni" (Castle Dounie/Downie) refers to the ancestral Castle and Clan seat, which once existed near the present Beaufort Castle. The second is "A Mhòr-fhaiche" (The Great Field).[15]

In 1429, the Clan Fraser of Lovat defeated the Clan Donald at the Battle of Mamsha.[22][23]

According to some accounts the Frasers under Lord Lovat supported the Munros at the Battle of Bealach nam Broig in 1452 which was fought against the Clan Mackenzie.[24][25][26][27] There are also accounts of Fraser Lord Lovat supporting the Munros at the Battle of Clachnaharry fought two years later in 1454.[28][29][30]

In 1544, the Frasers fought a great clan battle, the Battle of the Shirts (Blar-na-Léine in Gaelic) against the Clan Macdonald of Clanranald, over the disputed chiefship of Clan Ranald.[21] The Frasers, as part of a large coalition, backed a son of the 5th Chief, Ranald Gallda (the Stranger), which the MacDonalds found unacceptable.[21] The Earl of Argyll intervened, refusing to let the two forces engage. But on their march home, the 300 Frasers were ambushed by 500 MacDonalds. Only five Frasers and eight MacDonalds are said to have survived the battle. Both the clan chief, Hugh Fraser, 3rd Lord Lovat, and his son were amongst the dead and were buried at Beauly Priory.[15][21]

At the Siege of Inverness in 1562 the Clan Fraser of Lovat supported Mary, Queen of Scots: Scottish historian George Buchanan, a contemporary, wrote that when the unfortunate princess went to Inverness in 1562: "as soon as they heard of their sovereign's danger, a great number of the most eminent Scots poured in around her, especially the Frasers and Munros, who were esteemed the most 'valiant of the clans inhabiting those countries in the north.' " These two clans took Inverness Castle for the Queen. The Queen later hanged the governor, a Gordon who had refused her admission.[31]

In the 16th century a battle took place between the Clan Fraser (with help from the Clan MacRae) and the Clan Logan at Kessock, where Gilligorm, the Chief of the Clan Logan, was killed.[32]

17th century and civil war

In 1645, at the Battle of Auldearn, in Nairnshire, the Clan opposed the Royalist leader James Graham, 1st Marquess of Montrose, and fought under a Fraser of Struy (from a small village at the mouth of Glen Strathfarrar). The battle left eighty-seven Fraser widows.[33] A poem about the battle reads:[15]

"Here Fraser Fraser kills, a Browndoth kills a Browndoth.

A Bold a Bold, and Lieth's by Lieth overthrown.

A Forbes against a Forbes and her doeth stand,

And Drummonds fight with Drummonds hand to hand.

There dith Magill cause a Magill to die,

And Gordon doth the strength of Gordon try.

Oh! Scotland, were though Mad? Off thine own native gore.

So Much till now thou never shedst before."

In 1649 the Clan Fraser of Lovat, under Colonel Hugh Fraser, assaulted Inverness Castle for a second time, this time during a royalist rising, along with John Munro of Lemlair, Thomas Urquhart and Thomas Mackenzie of Pluscardine. They were all opposed to the authority of the current parliament, assaulted the town and took the castle in what is now known as the Siege of Inverness (1649). They then expelled the garrison and raised the fortifications. However, on the approach of the parliamentary forces led by General Leslie, the clans retreated back into Ross-shire. Over the next year, several skirmishes took place between these parties.[34] During the Siege of Inverness (1650) the Covenanter Frasers of Lovat under Sir James Fraser of Brea successfully defended Inverness Castle against the royalists.[35] In 1650, at the Battle of Dunbar, the Clan Fraser fought against the forces of Oliver Cromwell. However, the Covenanters were defeated.[36] In 1651, the Clan Fraser joined the army of Charles II at Stirling. They fought at the Battle of Worcester where the King's army was defeated by Oliver Cromwell's New Model Army.[37]

In 1689, the Glorious Revolution deposed the Roman Catholic King James VII as monarch of England, replacing the King with his Protestant daughter Mary and her husband and cousin William of Orange. Swiftly following in March, a Convention of the Estates was convened in Edinburgh, which supported William & Mary as joint monarchs of Scotland. However, to much of Scotland, particularly in the Highlands, James was still considered the rightful, legitimate King.

On 16 April 1689 John Graham of Claverhouse, Viscount of Dundee, later known as Bonnie Dundee, raised the royal standard of the recently deposed King James VII on the hilltop of Dundee Law. Many of the Highland clans rallied swiftly to his side. The chief of the Clan Fraser, Hugh Fraser, tried to keep the members of his clan from joining the uprising, to no avail: The Clan marched without him, and fought at the Battle of Killiecrankie.[38]

18th century and Jacobite risings

Jacobite rising of 1715

During the Jacobite rising of 1715, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat "the Fox", Chief at the time, supported the British Government and surrounded the Jacobite garrison in Inverness.[39] The Clan MacDonald of Keppoch attempted to relieve the garrison, but when their path was blocked by the Frasers, Keppoch retreated.[39][40] The Inverness garrison surrendered to Fraser on the same day that the Battle of Sheriffmuir was fought, and another Jacobite force was defeated at the Battle of Preston. In 1719 during the Jacobite rising of that year the British General, Joseph Wightman, passed through Fraser country en route to the Battle of Glen Shiel and gathered with him Fraser of Lovat's men as he went.[41] General Wade's report on the Highlands in 1724, estimated the clan strength at 800 men.[42]

Jacobite rising of 1745

In 1725 the British Field Marshall George Wade gave instructions that had come to him from George I of Great Britain to re-establish the Independent Highland Companies of soldiers to support the British Government.[43] Chief Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat was appointed as Captain of one of these Independent Highland Companies.[43] However, Wade complained to George II of Great Britain that the Independent Highland Companies had been infiltrated by Jacobitism and demanded that the king take action.[44] Wade put up Lord Lovat's captaincy as the first to go.[44] In 1740 George II demanded action and Wade stepped in and stripped Lovat of his company of Frasers, putting them under command elsewhere.[45] Wade also advised the government to remove Lord Lovat from his office as High Sheriff of Inverness-shire.[45] As a result, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat later gave his support to the Jacobite leader Charles Edward Stuart (Bonnie Prince Charlie), and when asked why he had engaged with the Prince after receiving so many favours from the government, he replied that "he did it more in revenge to the ministry for having taken away his Independent Company, than anything else".[46] Frasers were on the front lines of the Jacobite army at the Battle of Falkirk, and the Battle of Culloden in 1746.[47]

.jpg)

At Culloden, Charles Fraser of Inverallochy who led the clan at the battle, was mortally wounded and found by General Hawley on the field, who ordered one of his aides, a young James Wolfe to finish him off with a pistol. Wolfe refused, so Hawley got a common soldier to do it.[47] David Fraser of Glen Urquhart, who was deaf and mute, had, it was said, charged and killed seven redcoats, but was captured and died in prison.[47] John Fraser, also called 'MacIver' was shot in the knee, taken prisoner and put before a firing squad, but was then rescued by a British officer, Lord Boyd, who was sick of the slaughter. Another John Fraser, who was Provost of Inverness, tried to get fair treatment for the prisoners.[47] As the first of the Jacobites fleeing from Culloden approached Inverness they were met by a battalion of Frasers led by the 11th Lord Lovat's son, Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat.[48] Tradition states that the Master of Lovat immediately about-turned his men and marched down the road back towards Inverness, with pipes playing and colours flying.[48] There are however varying traditions as to what happened at the bridge which spans the River Ness.[48] One tradition is that Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat intended to hold the bridge until he was persuaded against it.[48] Another is that the bridge was seized by a party of the Campbell of Argyll Militia who were involved in a skirmish when blocking the crossing of retreating Jacobites.[48] While it is almost certain there was a skirmish upon the bridge, it has been proposed that Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat shrewdly switched sides and turned upon the fleeing Jacobites.[48] Such an act would explain his remarkable rise in fortune in the years that followed.[48] Imprisoned for a year, he was pardoned in 1750 and later raised a Fraser regiment for the British Army which fought in Canada in the 1750s, including Quebec.[47]

After the battle, the same year, Castle Dounie was burnt to the ground, while the Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat "the Fox" was on the run. He was captured, tried for treason, and executed in London on 9 April 1747, and his estates and titles were forfeited to the Crown.[47]

Aftermath of Culloden

Castle Dounie was replaced by a small square building costing £300 in which the Royal Commissioner resided until 1774, when some of the forfeited Lovat estates were granted by an Act of Parliament to his son, Simon Fraser, Master of Lovat (1726–1782), by then a major general, in recognition of his military service to the Crown and the payment of some £20,000.[47] Later, two modest wings were added. On the death of General Fraser's younger half-brother, Colonel Archibald Campbell Fraser of Lovat (1736–1815), without legitimate surviving male issue, the Lovat estates were transferred, by entail, to Thomas Alexander Fraser of Strichen (1802–1875), a distant cousin who was descended from Thomas Fraser of Knockie & Strichen (1548–1612), second son of Alexander Fraser, 4th Lord Lovat (1527–1557). Knockie was sold about 1727 to Hugh Fraser of Balnain (1702–1735).[47]

Frasers in the New World

Seven Years' War

Under the chief, Simon (who had led the Frasers in the '45 as the Master of Lovat) a regiment of Frasers, the 78th Fraser Highlanders, numbering fourteen hundred were raised and fought the French and Indians in the colonies and in Canada, from 1757 to 1759. The 78th fought under General Wolfe, who had previously fought at the Battle of Culloden, against Simon and perhaps some of the 78th. It was one of the 78th, possibly Simon, possibly one of his men, whose familiarity with the French language saved the first wave of British troops at the Battle of the Plains of Abraham, which led to the capture of Quebec.[47]

American rebellion

In the fight against American independence Simon, who was by this time a General, raised 2,300 men; the 71st Fraser Highlanders. He recruited two battalions at Inverness, Stirling and Glasgow. Most of the men were not Frasers for the number of Frasers had been substantially reduced after the battle of Culloden and the end of the clan system.[47]

Diaspora

Many Frasers settled in Canada and the United States after the war against the French in Quebec. Many others later emigrated to those countries and to Australia and New Zealand (which have both had a Fraser prime minister). Frasers in the US have continued their proud military tradition, fighting on both sides of the American Civil War. Frasers from both sides of the Atlantic fought in the First World War, and the Second World War.[49]

Fraser tartans

Lovat Tartan

Lovat Tartan Green Fraser Gathering Tartan

Green Fraser Gathering Tartan

Two chiefs

On 1 May 1984, by decree of the Court of the Lord Lyon, the 21st Lady Saltoun, a member of the Royal Family, was made "Chief of the name and arms of the whole Clan Fraser". Lord Lovat, Simon Christopher Joseph Fraser, was reported to have not given any heed to the decision, dismissing the matter as being beneath him.[50] Since this decree, there has been much confusion as to who is the Chief of the Clan Fraser.

Many believe that this decree made the Lady Saltoun the chief of the Clan. However, the Lord Lyon did not grant the chiefship of the Clan Fraser, just a description of "Chief of the name and arms." The Lord Lyon does not have power over the Chief of a Highland Clan.[51] What the decree did was reinforce the Lady Saltoun's claim to being the head of the senior branch of the wider Fraser family, and granted her the use of the plain and undifferenced Fraser arms (three strawberry flowers on a field of blue).[49]

The Arms of Lady Saltoun as Head of the Name & Arms of Fraser. – Azure three fraises Argent.

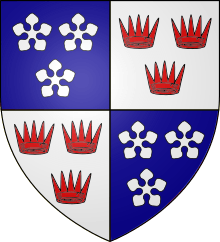

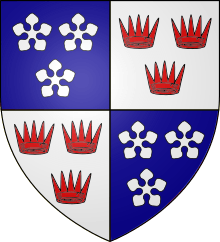

The Arms of Lady Saltoun as Head of the Name & Arms of Fraser. – Azure three fraises Argent. The Arms of Fraser of Lovat – Quarterly 1st & 4th Azure three fraises Argent 2nd & 3rd Argent three antique crowns Gules.

The Arms of Fraser of Lovat – Quarterly 1st & 4th Azure three fraises Argent 2nd & 3rd Argent three antique crowns Gules.

The arms of Clan Fraser of Lovat are Quarterly 1st & 4th Azure three fraises Argent 2nd & 3rd Argent three antique crowns Gules., or in layman's terms, the traditional three cinquefoils, or fraises (strawberry flowers), as they have come to be known, in the first and fourth positions and three crowns in the second and third positions. Only the Lord Lovat is allowed use of these arms plain and undifferenced.[15]

Castles

Castles that have been owned by the Clan Fraser of Lovat have included amongst others:

- Castle Dounie was the name of the original seat of the chief of Clan Fraser of Lovat, located two and a half miles south-west of Beauly, Inverness-shire.[4] The original castle came to the Frasers of Lovat in the thirteenth century and was besieged by the English in 1303.[4] In 1650 Castle Dounie was captured and damaged by Oliver Cromwell.[4] The clan chief, Simon Fraser, 11th Lord Lovat was executed in 1747 for supporting the Jacobite cause and Castle Dounie was subsequently destroyed.[4] However his son, also called Simon, recovered the property in 1771.[4] The Fraser of Lovat titles were all restored by 1857 and the castle was re-built as Beaufort Castle in 1882.[4] The family had to sell the new castle in the 1990s because of debt, but they still live near Beauly.[4]

- Castle Heather, near Inverness, is the site of a castle held by the Frasers,[4] most notably as the seat of James Fraser of Castle Leathers.

- Cherry Island (Loch Ness), near Fort Augustus is the site of a castle once held by the Frasers and that is said to have had a brownie.[4]

- Dalcross Castle, at Dalcross, Inverness-shire was held by the Frasers of Lovat who built the castle in 1620, but it passed to the Mackintoshes in the early eighteenth century.[4]

- Erchless Castle, near Beauly, Inverness-shire, was held by the Frasers but passed by marriage to the Clan Chisholm in fifteenth century.[4]

- Moniack Castle, near Beauly, Inverness-shire, was held by the Frasers of Lovat.[4]

- Reelig House, near Beauly, Inverness-shire, has been held by the Frasers since the seventeenth century and the Frasers of Reelig still live there.[4]

Military regiments

Frasers have always been known for their fighting spirit and their skill in the art of war. Frasers have fought in many wars, from defending Scottish lands against invading Danes and Norse, to the Scottish Wars of Independence, to the Jacobite risings, both World Wars, and they continue to serve today. Among the organized regiments were an Independent Highland Company in 1745 that fought at the Battle of Culloden,[47] and The 2nd Highland Battalion, formed in January 1757.[47] The 62nd Regiment of Foot, formed 1757,[47] was soon redesignated as the 78th Fraser Highlanders in 1758, and retired as a fighting unit in 1763, but the unit is still active as a fund raising organization under the authority of the Lord Lovat.[47] The 71st Fraser Highlanders formed in October 1775, and consisted of two battalions raised at Inverness, Stirling and Glasgow for service in North America. They were disbanded in 1786.[47] The Fraser Fencibles Regiment was raised by Col. the Hon. Archibald Campbell Fraser of Lovat, as a home guard in the event of an invasion by Napoleon Bonaparte. The Fraser Fencibles served in the Irish Rebellion of 1798.[47] The Lovat Scouts, formed in January 1900 by Simon Joseph Fraser, for service in the Second Boer War, saw extensive action during the Great War and the Second World War, and now consist of a platoon, Company C, of the 51st Highland Volunteers.[47]

The modern Clan

Today the Clan Fraser is composed of many thousands all over the world. Large Fraser populations exist in Canada and the United States, and smaller populations are in Australia, New Zealand (both of which have had Fraser prime ministers), Turkey, South Africa, Argentina, Chile and Brazil (where the descendants of William Fraser 11th of Culbokie and Guisachan now live), not to mention those who never left Scotland. In 1951, the Lord Lovat Simon Christopher Joseph Fraser was able to muster some 7,000 Frasers to the family seat at Beaufort Castle,[52] and in 1997, some 30–40,000 Frasers from 21 different countries came to Castle Fraser over a period of four days for a worldwide Clan gathering.[53]

Clan Fraser in popular media

- The historical novel Outlander by author Diana Gabaldon features the fictional male protagonist Jamie Fraser of Clan Fraser of Lovat.

References

- Clan Fraser of Lovat Profile scotclans.com. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). "Prologue". The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. xxii. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Mac an Tàilleir, Iain. "Ainmean Pearsanta" (docx). Sabhal Mòr Ostaig. Retrieved 15 October 2009.

- Coventry, Martin. (2008). Castles of the Clans: The Strongholds and Seats of 750 Scottish Families and Clans. pp. 210–213. ISBN 978-1-899874-36-1.

- Fraser Name Meaning ancestry.com. Retrieved on 14 June 2015.

- Patrick Hanks, Richard Coates, Peter McClure (2016). The Oxford History of Family Names in Britain and Ireland. Volume 2. Oxford University Press. p. 970.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 26 June 2004. Retrieved 31 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Frank Adam, Thomas Innes. The Clans, Septs and Regiments of the Scottish Highlands. Retrieved on 26 December 2008 "The deed was executed on the one part by the Marquis de la Frezeliere, the Duc de Luxembourg, the Duc de Châtillon and the Prince of Tingrie; while on the other side the subscribers were Lord Lovat, his brother John Fraser with George Henry Fraser, Major of the Irish Regiment of Bourke in the French service."

- Retrieved on 26 December 2008 "Lord Lovat was a fugitive in France at the time, and he was befriendtid by the Marquis. He wrote his life in French, afterwards translated into English and published in 1796. In it he makes the following statement : – "The house of Frezel, or Frezeau de la Frezeliere, is one of the most ancient houses in France. It ascends by uninterrupted filiation, and without any unequal alliance, to the year 1030. It is able to establish by a regular proof sixty-four quarterings in its armorial bearings, and all noble. It has titles of seven hundred years standing in the abbey of Notre Dame de Novers in Touraine. And it is certain.""

- Bois, François-Alexandre Aubert de La Chesnaye Des (9 April 1773). "Dictionnaire de la noblesse, contenant les généalogies, l'histoire et la chronologie des familles nobles de France ..." Vve Duchesne (et M. Badier). Retrieved 9 April 2018 – via Google Books.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 31 March 2010. Retrieved 31 March 2010.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved on 26 December 2008

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 1 October 2011. Retrieved 31 August 2013.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) Retrieved on 26 December 2008

- Note: The name "Ricardus Fresle" appears in the original Latin version of the Domesday Book as a tenant-in-chief in Nottingham. Also the commune of Fresles (mentioned as Freeles around 1240) exists to this very day in Haute-Normandie.

- Anderson, William. The Scottish Nation. (Vol.2), p.258.

- Grant, Neil. (1987). Scottish Clans and Tartans. Crescent Books, New York, ISBN 0-517-49901-0.

- Fraser, Archibald Campbell. Annals... of the Frasers of Loveth. Clan Fraser Association for California, 2003. Ed. Diolain Fraser.

- Note that the French word fraisier "strawberry plant" is not recorded in French before the first part of the 14th century : and the word fraise first meant "all sort of fruit", "something not important" and the Old French word for strawberry was fraie, not fraise :

- Black, George Fraser. The Surnames of Scotland.

- Moncreiffe of that Ilk, Sir Ian. The Highland Clans, p.80-83.

- Barrow, G W S. The Kingdom of the Scots, p.331.

- Way, George and Squire, Romily. (1994). Collins Scottish Clan & Family Encyclopedia. (Foreword by The Rt Hon. The Earl of Elgin KT, Convenor, The Standing Council of Scottish Chiefs). pp. 144 – 145.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1896). History of the Frasers of Lovat, with genealogies of the principal families of the name: to which is added those of Dunballoch and Phopachy. Inverness: A. & W. Mackenzie. p. 58.

- Anderson, John (1825). Historical Account of the Family of Frisel Or Fraser, Particularly Fraser of Lovat. W. Blackwood. p. 65.

George Buchanan, Book XII. p. 69 and MS of Frasers in the Advocates Library

- Fraser, James (1905) [Edited from original manuscript (c.1674) with notes and introduction, by William Mackay]. Chronicles of the Frasers: the Wardlaw manuscript entitled 'Polichronicon seu policratica temporum, or, The true genealogy of the Frasers', 916–1674. Inverness: Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. pp. 82–83.

- Anderson, John (1825). Historical Account of the Family of Frisel Or Fraser, Particularly Fraser of Lovat. W. Blackwood. pp. 53-54.

Dingwalls.

Quoting from the MSS of Frasers, MSS of Mackenzies and MSS of Foulis family – in the Advocate's Library. - Mackenzie, Alexander (1894). History of the Mackenzies with Genealogies of the Principal Families of the Name. Inverness: A. and W. Mackenzie. pp. 76-79.

- Mackenzie, Alexander (1898). History of the Munros of Fowlis with Genealogies of the Principal Families of the Name. Inverness: A. and W. Mackenzie. pp. 17-21.

- Gordon, Robert (1813) [Printed from original manuscript 1580–1656]. A Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland. Edinburgh: Printed by George Ramsay and Co. for Archibald Constable and Company Edinburgh; and White, Cochrance and Co. London. pp. 46–47.

- Fraser, James (1905) [Edited from original manuscript (c.1674) with notes and introduction, by William Mackay]. Chronicles of the Frasers: the Wardlaw manuscript entitled 'Polichronicon seu policratica temporum, or, The true genealogy of the Frasers', 916–1674. Inverness: Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. pp. 84–87.

- Anderson, John (1825). Historical Account of the family of Frisel or Fraser, particularly Fraser of Lovat. Edinburgh: Printed at the University Press by T. and A. Constable for the Scottish History Society. pp. 54–55.

Quoting: Gordon, Sir Robert (1580–1656). A Genealogical History of the Earldom of Sutherland . p. 47

- Buchanan, George (1506 -1582). History of Scotland. Completed in 1579, first published in 1582 in Latin. Republished in 1827 in English by James Aikman. p. 461.

- Clan Logan. Electric Scotland. Retrieved 12 March 2007.

- Clan Fraser Society of Scotland and the UK Retrieved on 7 March 2007

- Suter, James. "Memorabilia of Inverness". (1822) Archived 15 July 2002 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 26 April 2006.

- Mackenzie, Alexander. (1896). History of the Frasers of Lovat, with genealogies of the principal families of the name: to which is added those of Dunballoch and Phopachy. pp. 179 – 181.

- Battles and Generals of the Civil Wars, H.C.B. Rogers, Seeley Service & Co.,London, 1968

- BBC. Battle of Worcester Retrieved 26 April 2006.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. 24. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. pp. 151–156. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Mackenzie, Alan (2006). "10". History of the Clan Mackenzie (PDF). Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. 202. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Johnston, Thomas Brumby; Robertson, James Alexander; Dickson, William Kirk (1899). "General Wade's Report". Historical Geography of the Clans of Scotland. Edinburgh and London: W. & A.K. Johnston. p. 26. Retrieved 16 February 2020.

- Simpson, Peter. (1996). The Independent Highland Companies, 1603–1760. p. 113. ISBN 0-85976-432-X.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. 245. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. 258. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Fraser, Sarah (2012). The Last Highlander: Scotland's Most Notorious Clan Chief, Rebel & Double Agent. p. 333. ISBN 978-0-00-722950-5.

- Harper, J.R. (1979) The Fraser Highlanders. The Society of The Montreal Military & Maritime Museum, Montreal.

- Reid, Stuart (2002). Culloden Moor 1746: The Death of the Jacobite Cause. Campaign series. 106. Osprey Publishing. ISBN 1-84176-412-4. pp. 88–90.

- Saltoun, Lady Flora Fraser. Two Chiefs. FraserChief, the website of the Lady Saltoun. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- "The Frasers of Philorth, Now Saltoun". Clan Fraser Association for California. Retrieved 11 February 2007.

- Maclean of Ardgour v. Maclean 1941 S.C. 613 from Documents of the Lord Lyon, from Heraldica.org

- Scottish Themes.com Archived 30 September 2007 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved on 11 February 2007.

- Clan Fraser Society of Canada Archived 3 September 2013 at the Wayback Machine Retrieved 11 February 2007.

External links

Fraser Societies