Circumcision

Circumcision is the removal of the foreskin from the human penis.[1][2] In the most common procedure, the foreskin is opened, adhesions are removed, and the foreskin is separated from the glans. After that, a circumcision device may be placed, and then the foreskin is cut off. Topical or locally injected anesthesia is used to reduce pain and physiologic stress.[3] The procedure is most often an elective surgery performed on babies and children for religious or cultural reasons.[4] Medically, circumcision is a treatment option for problematic cases of phimosis and balanoposthitis that do not resolve with other treatments, and for chronic urinary tract infections (UTIs).[5][6] It is contraindicated in cases of certain genital structure abnormalities or poor general health.[1][6]

| Circumcision | |

|---|---|

A circumcision performed in Central Asia, c. 1865–1872 | |

| ICD-10-PCS | 0VBT |

| ICD-9-CM | V50.2 |

| MeSH | D002944 |

| OPS-301 code | 5–640.2 |

| MedlinePlus | 002998 |

| eMedicine | 1015820 |

The positions of the world's major medical organizations range from a belief that elective circumcision of babies and children carries significant risks and offers no medical benefits to a belief that the procedure has a modest health benefit that outweighs small risks.[7] No major medical organization recommends circumcising all males, and no major medical organization recommends banning the procedure.[7] Ethical and legal questions regarding informed consent and human rights have been raised over the circumcision of babies and children for non-medical reasons; for these reasons, the procedure is controversial.[8][9]

Male circumcision reduces the risk of HIV infection among heterosexual men in sub-Saharan Africa.[10][11] Consequently, the World Health Organization (WHO) recommends consideration of circumcision as part of a comprehensive HIV prevention program in areas with high rates of HIV.[12] The effectiveness of using circumcision to prevent HIV in the developed world is unclear;[13] however, there is some evidence that circumcision reduces HIV infection risk for men who have sex with men.[14] Circumcision is also associated with reduced rates of cancer-causing forms of human papillomavirus (HPV),[15][16] and UTIs.[3] It also decreases the risk of cancer of the penis via effectively curing phimosis.[3] Prevention of these conditions is not seen as a justification for routine circumcision of infants in the Western world.[5] Studies of other sexually transmitted infections also suggest that circumcision is protective, including for men who have sex with men.[17] A 2010 review found circumcisions performed by medical providers to have a typical complication rate of 1.5% for babies and 6% for older children, with few cases of severe complications.[18] Bleeding, infection, and the removal of either too much or too little foreskin are the most common acute complications. Meatal stenosis is the most common long term complication.[19] Complication rates are higher when the procedure is performed by an inexperienced operator, in unsterile conditions, or in older children.[18] Circumcision does not appear to have a negative impact on sexual function.[20][21]

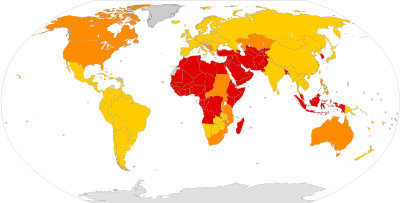

An estimated one-third of males worldwide are circumcised.[4][18][22] Circumcision is most common among Muslims and Jews (among whom it is near-universal for religious reasons), and in the United States, parts of Southeast Asia, and Africa.[4][23] It is relatively rare for non-religious reasons in Europe, Latin America, parts of Southern Africa, and most of Asia.[4] The origin of circumcision is not known with certainty; the oldest documented evidence for it comes from ancient Egypt.[4][24] Various theories have been proposed as to its origin including as a religious sacrifice and as a rite of passage marking a boy's entrance into adulthood.[25] It is part of religious law in Judaism[26] and is an established practice in Islam, Coptic Christianity, and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church.[4][27][28] The word circumcision is from Latin circumcidere, meaning "to cut around".[4]

Uses

Elective

Neonatal circumcision is usually elected by the parents for non-medical reasons, such as religious beliefs or personal preferences, possibly driven by societal norms.[6] Outside the parts of Africa with high prevalence of HIV/AIDS, the positions of the world's major medical organizations on non-therapeutic neonatal circumcision range from considering it as having a modest net health benefit that outweighs small risks, to viewing it as having no benefit with significant risks for harm.[7] No major medical organization recommends universal neonatal circumcision, and no major medical organization calls for banning it either.[7] The Royal Dutch Medical Association, which expresses some of the strongest opposition to routine neonatal circumcision, argues that while there are valid reasons for banning it, doing so could lead parents who insist on the procedure to turn to poorly trained practitioners instead of medical professionals.[7][29] This argument to keep the procedure within the purview of medical professionals is found across all major medical organizations.[7] In addition, the organizations advise medical professionals to yield to some degree to parental preferences, which are commonly based upon cultural or religious views, in their decision to agree to circumcise.[7] The Danish College of General Practitioners states that circumcision should "only [be done] when medically needed, otherwise it is a case of mutilation."[30]

Medical

Circumcision may be used to treat pathological phimosis, refractory balanoposthitis and chronic or recurrent urinary tract infections (UTIs).[5][6] The WHO promotes circumcision to prevent female-to-male HIV transmission in countries with high rates of HIV.[12] The International AIDS Society-USA also suggests circumcision be discussed with men who have insertive anal sex with men, especially in regions where HIV is common.[31]

The finding that circumcision significantly reduces female-to-male HIV transmission has prompted medical organizations serving communities affected by endemic HIV/AIDS to promote circumcision as an additional method of controlling the spread of HIV.[7] In 2007 the WHO and the Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS) recommended circumcision as part of a comprehensive program for prevention of HIV transmission in areas with high endemic rates of HIV, as long as the program includes "informed consent, confidentiality, and absence of coercion".[12]

Contraindications

Circumcision is contraindicated in infants with certain genital structure abnormalities, such as a misplaced urethral opening (as in hypospadias and epispadias), curvature of the head of the penis (chordee), or ambiguous genitalia, because the foreskin may be needed for reconstructive surgery. Circumcision is contraindicated in premature infants and those who are not clinically stable and in good health.[1][6][32] If an individual, child or adult, is known to have or has a family history of serious bleeding disorders (hemophilia), it is recommended that the blood be checked for normal coagulation properties before the procedure is attempted.[6][32]

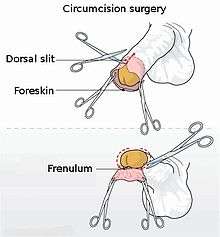

Technique

The foreskin extends out from the base of the glans and covers the glans when the penis is flaccid. Proposed theories for the purpose of the foreskin are that it serves to protect the penis as the fetus develops in the mother's womb, that it helps to preserve moisture in the glans, and that it improves sexual pleasure. The foreskin may also be a pathway of infection for certain diseases. Circumcision removes the foreskin at its attachment to the base of the glans.[4]

Removal of the foreskin

For infant circumcision, devices such as the Gomco clamp, Plastibell and Mogen clamp are commonly used in the USA.[3] These follow the same basic procedure. First, the amount of foreskin to be removed is estimated. The practitioner opens the foreskin via the preputial orifice to reveal the glans underneath and ensures it is normal before bluntly separating the inner lining of the foreskin (preputial epithelium) from its attachment to the glans. The practitioner then places the circumcision device (this sometimes requires a dorsal slit), which remains until blood flow has stopped. Finally, the foreskin is amputated.[3] For older babies and adults, circumcision is often performed surgically without specialized instruments,[32] and alternatives such as Unicirc, Prepex or the Shang ring are available.[33]

Pain management

The circumcision procedure causes pain, and for neonates this pain may interfere with mother-infant interaction or cause other behavioral changes,[34] so the use of analgesia is advocated.[3][35] Ordinary procedural pain may be managed in pharmacological and non-pharmacological ways. Pharmacological methods, such as localized or regional pain-blocking injections and topical analgesic creams, are safe and effective.[3][36][37] The ring block and dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB) are the most effective at reducing pain, and the ring block may be more effective than the DPNB. They are more effective than EMLA (eutectic mixture of local anesthetics) cream, which is more effective than a placebo.[36][37] Topical creams have been found to irritate the skin of low birth weight infants, so penile nerve block techniques are recommended in this group.[3]

For infants, non-pharmacological methods such as the use of a comfortable, padded chair and a sucrose or non-sucrose pacifier are more effective at reducing pain than a placebo,[37] but the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) states that such methods are insufficient alone and should be used to supplement more effective techniques.[3] A quicker procedure reduces duration of pain; use of the Mogen clamp was found to result in a shorter procedure time and less pain-induced stress than the use of the Gomco clamp or the Plastibell.[37] The available evidence does not indicate that post-procedure pain management is needed.[3] For adults, topical anesthesia, ring block, dorsal penile nerve block (DPNB) and general anesthesia are all options,[38] and the procedure requires four to six weeks of abstinence from masturbation or intercourse to allow the wound to heal.[32]

Effects

Sexually transmitted diseases

Human immunodeficiency virus

There is strong evidence that circumcision reduces the risk of men acquiring HIV infection in areas of the world with high rates of HIV.[10][11] Evidence among heterosexual men in sub-Saharan Africa shows an absolute decrease in risk of 1.8% which is a relative decrease of between 38% and 66% over two years,[11] and in this population studies rate it cost effective.[39] Whether it is of benefit in developed countries is undetermined.[13]

There are plausible explanations based on human biology for how circumcision can decrease the likelihood of female-to-male HIV transmission. The superficial skin layers of the penis contain Langerhans cells, which are targeted by HIV; removing the foreskin reduces the number of these cells. When an uncircumcised penis is erect during intercourse, any small tears on the inner surface of the foreskin come into direct contact with the vaginal walls, providing a pathway for transmission. When an uncircumcised penis is flaccid, the pocket between the inside of the foreskin and the head of the penis provides an environment conducive to pathogen survival; circumcision eliminates this pocket. Some experimental evidence has been provided to support these theories.[40]

The WHO and the UNAIDS state that male circumcision is an efficacious intervention for HIV prevention, but should be carried out by well-trained medical professionals and under conditions of informed consent (parents' consent for their infant boys).[4][12][41] The WHO has judged circumcision to be a cost-effective public health intervention against the spread of HIV in Africa, although not necessarily more cost-effective than condoms.[4] The joint WHO/UNAIDS recommendation also notes that circumcision only provides partial protection from HIV and should not replace known methods of HIV prevention.[12]

Male circumcision provides only indirect HIV protection for heterosexual women.[3][42][43] It is unknown whether or not circumcision reduces transmission when men engage in anal sex with a female partner.[41][44] Some evidence supports its effectiveness at reducing HIV risk in men who have sex with men.[14]

Human papillomavirus

Human papillomavirus (HPV) is the most commonly transmitted sexually transmitted infection, affecting both men and women. While most infections are asymptomatic and are cleared by the immune system, some types of the virus cause genital warts, and other types, if untreated, cause various forms of cancer, including cervical cancer, and penile cancer. Genital warts and cervical cancer are the two most common problems resulting from HPV.[45]

Circumcision is associated with a reduced prevalence of oncogenic types of HPV infection, meaning that a randomly selected circumcised man is less likely to be found infected with cancer-causing types of HPV than an uncircumcised man.[46][47] It also decreases the likelihood of multiple infections.[16] As of 2012 there was no strong evidence that it reduces the rate of new HPV infection,[15][16][48] but the procedure is associated with increased clearance of the virus by the body,[15][16] which can account for the finding of reduced prevalence.[16]

Although genital warts are caused by a type of HPV, there is no statistically significant relationship between being circumcised and the presence of genital warts.[15][47][48]

Other infections

Studies evaluating the effect of circumcision on the rates of other sexually transmitted infections have generally, found it to be protective. A 2006 meta-analysis found that circumcision was associated with lower rates of syphilis, chancroid and possibly genital herpes.[49] A 2010 review found that circumcision reduced the incidence of HSV-2 (herpes simplex virus, type 2) infections by 28%.[50] The researchers found mixed results for protection against trichomonas vaginalis and chlamydia trachomatis, and no evidence of protection against gonorrhea or syphilis.[50] It may also possibly protect against syphilis in men who have sex with men.[51]

Phimosis, balanitis and balanoposthitis

Phimosis is the inability to retract the foreskin over the glans penis.[52] At birth, the foreskin cannot be retracted due to adhesions between the foreskin and glans, and this is considered normal (physiological phimosis).[52] Over time the foreskin naturally separates from the glans, and a majority of boys are able to retract the foreskin by age three.[52] Less than one percent are still having problems at age 18.[52] If the inability to do so becomes problematic (pathological phimosis) circumcision is a treatment option.[5][53] This pathological phimosis may be due to scarring from the skin disease balanitis xerotica obliterans (BXO), repeated episodes of balanoposthitis or forced retraction of the foreskin.[54] Steroid creams are also a reasonable option and may prevent the need for surgery including in those with mild BXO.[54][55] The procedure may also be used to prevent the development of phimosis.[6] Phimosis is also a complication that can result from circumcision.[56]

An inflammation of the glans penis and foreskin is called balanoposthitis, and the condition affecting the glans alone is called balanitis.[57][58] Most cases of these conditions occur in uncircumcised males,[59] affecting 4–11% of that group.[60] The moist, warm space underneath the foreskin is thought to facilitate the growth of pathogens, particularly when hygiene is poor. Yeasts, especially Candida albicans, are the most common penile infection and are rarely identified in samples taken from circumcised males.[59] Both conditions are usually treated with topical antibiotics (metronidazole cream) and antifungals (clotrimazole cream) or low-potency steroid creams.[57][58] Circumcision is a treatment option for refractory or recurrent balanoposthitis, but in the twenty-first century the availability of the other treatments has made it less necessary.[57][58]

Urinary tract infections

A UTI affects parts of the urinary system including the urethra, bladder, and kidneys. There is about a one percent risk of UTIs in boys under two years of age, and the majority of incidents occur in the first year of life. There is good but not ideal evidence that circumcision of babies reduces the incidence of UTIs in boys under two years of age, and there is fair evidence that the reduction in incidence is by a factor of 3–10 times (100 circumcisions prevents one UTI).[3][61][62] Circumcision is most likely to benefit boys who have a high risk of UTIs due to anatomical defects,[3] and may be used to treat recurrent UTIs.[5]

There is a plausible biological explanation for the reduction in UTI risk after circumcision. The orifice through which urine passes at the tip of the penis (the urinary meatus) hosts more urinary system disease-causing bacteria in uncircumcised boys than in circumcised boys, especially in those under six months of age. As these bacteria are a risk factor for UTIs, circumcision may reduce the risk of UTIs through a decrease in the bacterial population.[3][62]

Cancers

Circumcision has a protective effect against the risks of penile cancer in men, and cervical cancer in the female sexual partners of heterosexual men. Penile cancer is rare, with about 1 new case per 100,000 people per year in developed countries, and higher incidence rates per 100,000 in sub-Saharan Africa (for example: 1.6 in Zimbabwe, 2.7 in Uganda and 3.2 in Eswatini).[63] The number of new cases is also high in some South American countries including Paraguay and Uruguay, at about 4.3 per 100,000.[64] It is least common in Israeli Jews—0.1 per 100,000—related in part to the very high rate of circumcision of babies.[65]

Penile cancer development can be detected in the carcinoma in situ (CIS) cancerous precursor stage and at the more advanced invasive squamous cell carcinoma stage.[3] Childhood or adolescent circumcision is associated with a reduced risk of invasive squamous cell carcinoma in particular.[3][63] There is an association between adult circumcision and an increased risk of invasive penile cancer; this is believed to be from men being circumcised as a treatment for penile cancer or a condition that is a precursor to cancer rather than a consequence of circumcision itself.[63] Penile cancer has been observed to be nearly eliminated in populations of males circumcised neonatally.[60]

Important risk factors for penile cancer include phimosis and HPV infection, both of which are mitigated by circumcision.[63] The mitigating effect circumcision has on the risk factor introduced by the possibility of phimosis is secondary, in that the removal of the foreskin eliminates the possibility of phimosis. This can be inferred from study results that show uncircumcised men with no history of phimosis are equally likely to have penile cancer as circumcised men.[3][63] Circumcision is also associated with a reduced prevalence of cancer-causing types of HPV in men[16] and a reduced risk of cervical cancer (which is caused by a type of HPV) in female partners of men.[6] As penile cancer is rare (and may become increasingly rare as HPV vaccination rates rise), and circumcision has risks, the practice is not considered to be valuable solely as a prophylactic measure against penile cancer in the United States.[3][60][66]

There is some evidence that circumcision is associated with lower risk of prostate cancer. A 2015 meta-analysis found a reduced risk of prostate cancer associated with circumcision in black men.[67] A 2016 meta-analysis found that men with prostate cancer were less likely to be circumcised.[68]

Women's health

A 2017 systematic review found consistent evidence that male circumcision prior to heterosexual contact was associated with a decreased risk of cervical cancer, cervical dysplasia, HSV-2, chlamydia, and syphilis among women. The evidence was less consistent in regards to the potential association of circumcision with women's risk of HPV and HIV.[69]

Adverse effects

Neonatal circumcision is generally safe when done by an experienced practitioner.[70][71] The most common acute complications are bleeding, infection and the removal of either too much or too little foreskin.[3][72] These complications occur in approximately 0.13% of procedures, with bleeding being the most common acute complication in the United States.[72] Minor complications are reported to occur in three percent of procedures.[70] Severe complications are rare.[73] A specific complication rate is difficult to determine due to scant data on complications and inconsistencies in their classification.[3] Complication rates are greater when the procedure is performed by an inexperienced operator, in unsterile conditions, or when the child is at an older age.[18] Significant acute complications happen rarely,[3][18] occurring in about 1 in 500 newborn procedures in the United States.[3] Severe to catastrophic complications, including death, are so rare that they are reported only as individual case reports.[3][71] Where a Plastibell device is used, the most common complication is the retention of the device occurring in around 3.5% of procedures.[19] Other possible complications include buried penis, chordee, phimosis, skin bridges, urethral fistulas, and meatal stenosis.[71][74] These complications may be partly avoided with proper technique, and are often treatable without requiring surgical revision.[71] The most common long-term complication is meatal stenosis, this is almost exclusively seen in circumcised children, it is thought to be caused by ammonia producing bacteria coming into contact with the meatus in circumcised infants.[19] It can be treated by meatotomy.[19]

Pain

Effective pain management should be used.[3] Inadequate pain relief may carry the risks of heightened pain response for newborns.[34] Newborns that experience pain due to being circumcised have different responses to vaccines given afterwards, with higher pain scores observed.[75] For adult men who have been circumcised, there is a risk that the circumcision scar may be tender.[76]

Sexual effects

The question of how circumcision affects penile sensitivity and sexual satisfaction is controversial; some research has found a loss of sensation while other research has found enhanced sensation.[77] The highest quality evidence indicates that circumcision does not decrease the sensitivity of the penis, harm sexual function or reduce sexual satisfaction.[20][78][79] A 2013 systematic review found that circumcision did not appear to adversely affect sexual desire, pain with intercourse, premature ejaculation, time until ejaculation, erectile dysfunction or difficulties with orgasm.[80] However, the study found that the existing evidence is not very good.[80] A 2017 review found that circumcision did not affect premature ejaculation.[81] When it comes to sexual partners' experiences, circumcision has an unclear effect as it has not been well studied.[82]

Reduced sexual sensation is a possible complication of male circumcision.[76]

Psychological effects

In general, there is controversy over whether non-therapeutic circumcision can confer psychological benefits, or whether it causes psychological harms.[83]

Overall, as of 2019 it is unclear what the psychological outcomes of circumcision are, with some studies showing negative effects, and others showing that the effects are negligible.[84] There is no good evidence that circumcision adversely affects cognitive abilities or that it induces post-traumatic stress disorder.[84] There is debate in the literature over whether the pain of circumcision has lasting psychological impact, with only weak underlying data available.[84]

Prevalence

Circumcision is one of the world's most widely performed medical procedures.[24] Approximately 37% to 39% of males worldwide are circumcised, about half for religious or cultural reasons.[85] It is most often practiced between infancy and the early twenties.[4] The WHO estimated in 2007 that 664,500,000 males aged 15 and over were circumcised (30–33% global prevalence), almost 70% of whom were Muslim.[4] Circumcision is most common in the Muslim world, Israel, South Korea, the United States and parts of Southeast Asia and Africa. It is relatively rare in Europe, Latin America, parts of Southern Africa and Oceania and most of non-Muslim Asia. Prevalence is near-universal in the Middle East and Central Asia.[4][86] Non-religious circumcision in Asia, outside of the Republic of Korea and the Philippines, is fairly rare,[4] and prevalence is generally low (less than 20%) across Europe.[4][87] Estimates for individual countries include Taiwan at 9%[88] and Australia 58.7%.[89] Prevalence in the United States and Canada is estimated at 75% and 30% respectively.[4] Prevalence in Africa varies from less than 20% in some southern African countries to near universal in North and West Africa.[86]

The rates of routine neonatal circumcision over time have varied significantly by country. In the United States, hospital discharge surveys estimated rates at 64.7% in the year 1980, 59.0% in the year 1990, 62.4% in the year 2000, and 58.3% in the year 2010.[90] These estimates are lower than the overall circumcision rates, as they do not account for non-hospital circumcisions,[90] or for procedures performed for medical or cosmetic reasons later in life;[4][90] community surveys have reported higher neonatal circumcision.[4] Canada has seen a slow decline since the early 1970s, possibly influenced by statements from the AAP and the Canadian Pediatric Society issued in the 1970s saying that the procedure was not medically indicated.[4] In Australia, the rate declined in the 1970s and 80s, but has been increasing slowly as of 2004.[4] In the United Kingdom, rates are likely to have been 20–30% in the 1940s but declined at the end of that decade. One possible reason may have been a 1949 British Medical Journal article which stated that there was no medical reason for the general circumcision of babies.[4] The overall prevalence of circumcision in South Korea has increased markedly in the second half of the 20th century, rising from near zero around 1950 to about 60% in 2000, with the most significant jumps in the last two decades of that time period.[4] This is probably due to the influence of the United States, which established a trusteeship for the country following World War II.[4]

Medical organizations can affect the neonatal circumcision rate of a country by influencing whether the costs of the procedure are borne by the parents or are covered by insurance or a national health care system.[7] Policies that require the costs to be paid by the parents yield lower neonatal circumcision rates.[7] The decline in the rates in the UK is one example; another is that in the United States, the individual states where insurance or Medicaid covers the costs have higher rates.[7] Changes to policy are driven by the results of new research, and moderated by the politics, demographics, and culture of the communities.[7]

History

Circumcision is the world's oldest planned surgical procedure, suggested by anatomist and hyperdiffusionist historian Grafton Elliot Smith to be over 15,000 years old, pre-dating recorded history. There is no firm consensus as to how it came to be practiced worldwide. One theory is that it began in one geographic area and spread from there; another is that several different cultural groups began its practice independently. In his 1891 work History of Circumcision, physician Peter Charles Remondino suggested that it began as a less severe form of emasculating a captured enemy: penectomy or castration would likely have been fatal, while some form of circumcision would permanently mark the defeated yet leave him alive to serve as a slave.[25][91]

The history of the migration and evolution of the practice of circumcision is followed mainly through the cultures and peoples in two separate regions. In the lands south and east of the Mediterranean, starting with Sudan and Ethiopia, the procedure was practiced by the ancient Egyptians and the Semites, and then by the Jews and Muslims, with whom the practice travelled to and was adopted by the Bantu Africans. In Oceania, circumcision is practiced by the Australian Aboriginals and Polynesians.[91] There is also evidence that circumcision was practiced among the Aztec and Mayan civilizations in the Americas,[4] but little detail is available about its history.[24][25]

Middle East, Africa and Europe

Evidence suggests that circumcision was practiced in the Middle East by the 4th millennium BCE, when the Sumerians and the Semites moved into the area that is modern-day Iraq from the North and West.[24] The earliest historical record of circumcision comes from Egypt, in the form of an image of the circumcision of an adult carved into the tomb of Ankh-Mahor at Saqqara, dating to about 2400–2300 BCE. Circumcision was done by the Egyptians possibly for hygienic reasons, but also was part of their obsession with purity and was associated with spiritual and intellectual development. No well-accepted theory explains the significance of circumcision to the Egyptians, but it appears to have been endowed with great honor and importance as a rite of passage into adulthood, performed in a public ceremony emphasizing the continuation of family generations and fertility. It may have been a mark of distinction for the elite: the Egyptian Book of the Dead describes the sun god Ra as having circumcised himself.[25][91]

Though secular scholars consider the story to be literary and not historical,[92] circumcision features prominently in the Hebrew Bible. The narrative in Genesis chapter 17 describes the circumcision of Abraham and his relatives and slaves. In the same chapter, Abraham's descendants are commanded to circumcise their sons on the eighth day of life as part of a covenant with God.

In addition to proposing that circumcision was taken up by the Israelites purely as a religious mandate, scholars have suggested that Judaism's patriarchs and their followers adopted circumcision to make penile hygiene easier in hot, sandy climates; as a rite of passage into adulthood; or as a form of blood sacrifice.[24][91][93]

Alexander the Great conquered the Middle East in the 4th century BCE, and in the following centuries ancient Greek cultures and values came to the Middle East. The Greeks abhorred circumcision, making life for circumcised Jews living among the Greeks (and later the Romans) very difficult. Antiochus Epiphanes outlawed circumcision, as did Hadrian, which helped cause the Bar Kokhba revolt. During this period in history, Jewish circumcision called for the removal of only a part of the prepuce, and some Hellenized Jews attempted to look uncircumcised by stretching the extant parts of their foreskins. This was considered by the Jewish leaders to be a serious problem, and during the 2nd century CE they changed the requirements of Jewish circumcision to call for the complete removal of the foreskin,[94] emphasizing the Jewish view of circumcision as intended to be not just the fulfillment of a Biblical commandment but also an essential and permanent mark of membership in a people.[91][93]

A narrative in the Christian Gospel of Luke makes a brief mention of the circumcision of Jesus, but the subject of physical circumcision itself is not part of the received teachings of Jesus. Paul the Apostle reinterpreted circumcision as a spiritual concept, arguing the physical one to be unnecessary for Gentile converts to Christianity. The teaching that physical circumcision was unnecessary for membership in a divine covenant was instrumental in the separation of Christianity from Judaism. Although it is not explicitly mentioned in the Quran (early 7th century CE), circumcision is considered essential to Islam, and it is nearly universally performed among Muslims. The practice of circumcision spread across the Middle East, North Africa, and Southern Europe with Islam.[95]

Genghis Khan and the following Yuan Emperors in China forbade Islamic practices such as halal butchering and circumcision.[96][97] This led Chinese Muslims to eventually take an active part in rebelling against the Mongols and installing the Ming Dynasty.

The practice of circumcision is thought to have been brought to the Bantu-speaking tribes of Africa by either the Jews after one of their many expulsions from European countries, or by Muslim Moors escaping after the 1492 reconquest of Spain. In the second half of the 1st millennium CE, inhabitants from the North East of Africa moved south and encountered groups from Arabia, the Middle East, and West Africa. These people moved south and formed what is known today as the Bantu. Bantu tribes were observed to be upholding what was described as Jewish law, including circumcision, in the 16th century. Circumcision and elements of Jewish dietary restrictions are still found among Bantu tribes.[24]

Indigenous peoples

Circumcision is practiced by some groups amongst Australian Aboriginal peoples, Polynesians, and Native Americans. Little information is available about the origins and history of circumcision among these peoples, compared to circumcision in the Middle East.

For Aboriginal Australians and Polynesians, circumcision likely started as a blood sacrifice and a test of bravery and became an initiation rite with attendant instruction in manhood in more recent centuries. Often seashells were used to remove the foreskin, and the bleeding was stopped with eucalyptus smoke.[24][98]

Christopher Columbus reported circumcision being practiced by Native Americans.[25] It was also practiced by the Incas, Aztecs, and Mayans. It probably started among South American tribes as a blood sacrifice or ritual mutilation to test bravery and endurance, and its use later evolved into a rite of initiation.[24]

Modern times

Circumcision did not become a common medical procedure in the Anglophone world until the late 19th century.[99] At that time, British and American doctors began recommending it primarily as a deterrent to masturbation.[99][100] Prior to the 20th century, masturbation was believed to be the cause of a wide range of physical and mental illnesses including epilepsy, paralysis, impotence, gonorrhea, tuberculosis, feeblemindedness, and insanity.[101][102] In 1855, motivated in part by an interest in promoting circumcision to reduce masturbation, English physician Jonathan Hutchinson published his findings that Jews had a lower prevalence of certain venereal diseases.[103] While pursuing a successful career as a general practitioner, Hutchinson went on to advocate circumcision for health reasons for the next fifty years,[103] and eventually earned a knighthood for his overall contributions to medicine.[104] In America, one of the first modern physicians to advocate the procedure was Lewis Sayre, a founder of the American Medical Association. In 1870, Sayre began using circumcision as a purported cure for several cases of young boys diagnosed with paralysis or significant motor problems. He thought the procedure ameliorated such problems based on a "reflex neurosis" theory of disease, which held that excessive stimulation of the genitals was a disturbance to the equilibrium of the nervous system and a cause of systemic problems.[99] The use of circumcision to promote good health also fit in with the germ theory of disease during that time, which saw the foreskin as being filled with infection-causing smegma (a mixture of shed skin cells and oils). Sayre published works on the subject and promoted it energetically in speeches. Contemporary physicians picked up on Sayre's new treatment, which they believed could prevent or cure a wide-ranging array of medical problems and social ills. Its popularity spread with publications such as Peter Charles Remondino's History of Circumcision. By the turn of the century infant circumcision was near universally recommended in America and Great Britain.[25][100] David Gollaher proposes that "Americans found circumcision appealing not merely on medical grounds, but also for its connotations of science, health, and cleanliness—newly important class distinctions" in a country where 17 million immigrants arrived between 1890 and 1914.[105]

After the end of World War II, Britain implemented a National Health Service, and so looked to ensure that each medical procedure covered by the new system was cost-effective and the procedure for non-medical reasons was not covered by the national healthcare system. Douglas Gairdner's 1949 article "The Fate of the Foreskin" argued that the evidence available at that time showed that the risks outweighed the known benefits.[106] Circumcision rates dropped in Britain and in the rest of Europe. In the 1970s, national medical associations in Australia and Canada issued recommendations against routine infant circumcision, leading to drops in the rates of both of those countries. The United States made similar statements in the 1970s, but stopped short of recommending against it, simply stating that it has no medical benefit. Since then they have amended their policy statements several times, with the current recommendation being that the benefits outweigh the risks, but they do not recommend it routinely.[25][100]

An association between circumcision and reduced heterosexual HIV infection rates was suggested in 1986.[25] Experimental evidence was needed to establish a causal relationship, so three randomized controlled trials were commissioned as a means to reduce the effect of any confounding factors.[11] Trials took place in South Africa, Kenya and Uganda.[11] All three trials were stopped early by their monitoring boards because those in the circumcised group had a lower rate of HIV contraction than the control group.[11] Subsequently, the World Health Organization promoted circumcision in high-risk populations as part of an overall program to reduce the spread of HIV,[12] although some have challenged the validity of the African randomized controlled trials, prompting a number of researchers to question the effectiveness of circumcision as an HIV prevention strategy.[107][108][109][110] The Male Circumcision Clearinghouse website was formed in 2009 by WHO, UNAIDS, FHI and AVAC to provide current evidence-based guidance, information, and resources to support the delivery of safe male circumcision services in countries that choose to scale up the procedure as one component of comprehensive HIV prevention services.[111][112]

Society and culture

Cultures and religions

In some cultures, males are generally required to be circumcised shortly after birth, during childhood or around puberty as part of a rite of passage. Circumcision is commonly practiced in the Jewish and Islamic faiths and in Coptic Christianity and the Ethiopian Orthodox Church and the Eritrean Orthodox Tewahedo Church.[7][26][27][28][113][114][115]

Judaism

Circumcision is very important to most branches of Judaism, with over 90% of male adherents having the procedure performed as a religious obligation. The basis for its observance is found in the Torah of the Hebrew Bible, in Genesis chapter 17, in which a covenant of circumcision is made with Abraham and his descendants. Jewish circumcision is part of the brit milah ritual, to be performed by a specialist ritual circumciser, a mohel, on the eighth day of a newborn son's life, with certain exceptions for poor health. Jewish law requires that the circumcision leaves the glans bare when the penis is flaccid. Converts to Conservative and Orthodox Judaism must also be circumcised; those who are already circumcised undergo a symbolic circumcision ritual. Circumcision is not required by Judaism for one to be considered Jewish, but some adherents foresee serious negative spiritual consequences if it is neglected.[26][116]

According to traditional Jewish law, in the absence of an adult free Jewish male expert, a woman, a slave, or a child who has the required skills is also authorized to perform the circumcision, provided that they are Jewish.[117] However, most streams of non-Orthodox Judaism allow female mohels, called mohalot (Hebrew: מוֹהֲלוֹת, the plural of מוֹהֶלֶת mohelet, feminine of mohel), without restriction. In 1984 Deborah Cohen became the first certified Reform mohelet; she was certified by the Berit Mila program of Reform Judaism.[118] Some contemporary Jews in the United States choose not to circumcise their sons.[119] They are assisted by a small number of Reform and Reconstructionist rabbis, and have developed a welcoming ceremony that they call the brit shalom ("Covenant [of] Peace") for such children, also accepted by Humanistic Judaism.[120][121]

This ceremony of brit shalom is not officially approved of by the Reform or Reconstructionist rabbinical organizations, who make the recommendation that male infants should be circumcised, though the issue of converts remains controversial[122][123] and circumcision of converts is not mandatory in either movement.[124]

Islam

Although there is some debate within Islam over whether it is a religious requirement, circumcision (called khitan) is practiced nearly universally by Muslim males. Islam bases its practice of circumcision on the Genesis 17 narrative, the same Biblical chapter referred to by Jews. The procedure is not explicitly mentioned in the Quran, however, it is a tradition established by Islam's prophet Muhammad directly (following Abraham), and so its practice is considered a sunnah (prophet's tradition) and is very important in Islam. For Muslims, circumcision is also a matter of cleanliness, purification and control over one's baser self (nafs). There is no agreement across the many Islamic communities about the age at which circumcision should be performed. It may be done from soon after birth up to about age 15; most often it is performed at around six to seven years of age. The timing can correspond with the boy's completion of his recitation of the whole Quran, with a coming-of-age event such as taking on the responsibility of daily prayer or betrothal. Circumcision may be celebrated with an associated family or community event. Circumcision is recommended for, but is not required of, converts to Islam.[28][113][125]

Christianity

The New Testament chapter Acts 15 records that Christianity did not require circumcision. In 1442 the Catholic Church banned the practice of religious circumcision in the 11th Council of Florence [126] and currently maintains a neutral position on the practice of non-religious circumcision.[127] Coptic Christians practice circumcision as a rite of passage.[4][27][115][128] The Ethiopian Orthodox Church calls for circumcision, with near-universal prevalence among Orthodox men in Ethiopia.[4] Some Christian churches in South Africa disapprove of the practice, while others require it of their members.[4]

African cultures

Certain African cultural groups, such as the Yoruba and the Igbo of Nigeria, customarily circumcise their infant sons. The procedure is also practiced by some cultural groups or individual family lines in Sudan, Democratic Republic of the Congo, Uganda and in southern Africa. For some of these groups, circumcision appears to be purely cultural, done with no particular religious significance or intention to distinguish members of a group. For others, circumcision might be done for purification, or it may be interpreted as a mark of subjugation. Among these groups, even when circumcision is done for reasons of tradition, it is often done in hospitals.[114] The Maasai people, who live predominantly in Kenya and Tanzania, use circumcision as a rite of passage. It is also used for distinguished age groups. This is usually done after every fifteen years where a new "age set" are formed. The new members are to undergo initiation at the same time. Whenever new age groups are initiated, they will become novice warriors and replace the previous group. The new initiates will be given a unique name that will be an important marker of the history of the Maasai. No anesthesia is used, and initiates have to endure the pain or be called flinchers.[129] The Xhosa community practice circumcision as a sacrifice. In doing so, young boys will announce to their family members when they are ready for circumcision by singing. The sacrifice is the blood spilt during the initiation procedure. Young boys will be considered an "outsiders" unless they undergo circumcision.[130] It is not clear how many deaths and injuries result from non-clinical circumcisions.[131]

Australian cultures

Some Australian Aborigines use circumcision as a test of bravery and self-control as a part of a rite of passage into manhood, which results in full societal and ceremonial membership. It may be accompanied by body scarification and the removal of teeth, and may be followed later by penile subincision. Circumcision is one of many trials and ceremonies required before a youth is considered to have become knowledgeable enough to maintain and pass on the cultural traditions. During these trials, the maturing youth bonds in solidarity with the men. Circumcision is also strongly associated with a man's family, and it is part of the process required to prepare a man to take a wife and produce his own family.[114]

Filipino culture

In the Philippines, circumcision known as "tuli" is sometimes viewed as a rite of passage.[132] About 93% of Filipino men are circumcised.[132] Often this occurs, in April and May, when Filipino boys are taken by their parents. The practice dates back to the arrival of Islam in 1450. Pressure to be circumcised is even in the language: one Tagalog word for 'uncircumcised' is supot, meaning 'coward' literally. A circumcised eight or ten year-old is no longer considered a boy and is given more adult roles in the family and society.[133]

Ethical and legal issues

There is a long-running and vigorous debate over ethical concerns regarding circumcision, particularly neonatal circumcision for reasons other than intended direct medical benefit. There are three parties involved in the decision to circumcise a minor: the minor as the patient, the parents (or other guardians) and the physician. The physician is bound under the ethical principles of beneficence (promoting well-being) and non-maleficence ("first, do no harm"), and so is charged with the responsibility to promote the best interests of the patient while minimizing unnecessary harms. Those involved must weigh the factors of what is in the best interest of the minor against the potential harms of the procedure.[9]

With a newborn involved, the decision is made more complex due to the principles of respect for autonomy and consent, as a newborn cannot understand or engage in a logical discussion of his own values and best interests.[8][9] A mentally more mature child can understand the issues involved to some degree, and the physician and parents may elicit input from the child and weigh it appropriately in the decision-making process, although the law may not treat such input as legally informative. Ethicists and legal theorists also state that it is questionable for parents to make a decision for the child that precludes the child from making a different decision for himself later. Such a question can be raised for the decision by the parents either to circumcise or not to circumcise the child.[9]

Generally, circumcision on a minor is not ethically controversial or legally questionable when there is a clear and pressing medical indication for which it is the accepted best practice to resolve. Where circumcision is the chosen intervention, the physician has an ethical responsibility to ensure the procedure is performed competently and safely to minimize potential harms.[8][9] Worldwide, most legal jurisdictions do not have specific laws concerning the circumcision of males,[4] but infant circumcision is not illegal in many countries.[134] A few countries have passed legislation on the procedure: Germany allows non-therapeutic circumcision,[135] while non-religious routine circumcision is illegal in South Africa and Sweden.[4][134]

Throughout society, circumcision is often considered for reasons other than medical need. Public health advocates of circumcision consider it to have a net benefit, and therefore feel that increasing the circumcision rate is an ethical imperative. They recommend performing the procedure during the neonatal period when it is less expensive and has a lower risk of complications.[8] While studies show there is a modest epidemiological benefit to circumcision, critics argue that the number of circumcisions that would have to be performed would yield an overall negative public health outcome due to the resulting number of complications or other negative effects (such as pain). Pinto (2012) writes "sober proponents and detractors of circumcision agree that there is no overwhelming medical evidence to support either side."[8] This type of cost-benefit analysis is highly dependent on the kinds and frequencies of health problems in the population under discussion and how circumcision affects those health problems.[9]

Parents are assumed to have the child's best interests in mind. Ethically, it is imperative that the medical practitioner inform the parents about the benefits and risks of the procedure and obtain informed consent before performing it. Practically, however, many parents come to a decision about circumcising the child before he is born, and a discussion of the benefits and risks of the procedure with a physician has not been shown to have a significant effect on the decision. Some parents request to have their newborn or older child circumcised for non-therapeutic reasons, such as the parents' desires to adhere to family tradition, cultural norms or religious beliefs. In considering such a request, the physician may consider (in addition to any potential medical benefits and harms) such non-medical factors in determining the child's best interests and may ethically perform the procedure. Equally, without a clear medical benefit relative to the potential harms, a physician may take the ethical position that non-medical factors do not contribute enough as benefits to outweigh the potential harms and refuse to perform the procedure. Medical organization such as the British Medical Association state that their member physicians are not obliged to perform the procedure in such situations.[8][9]

In 2012 the International NGO Council on Violence against Children identified non-therapeutic circumcision of infants and boys as being among harmful practices that constitute violence against children and violate their rights.[136] The German Academy for Pediatric and Adolescent Medicine (Deutsche Akademie für Kinder- und Jugendmedizin e.V., DAKJ) recommend against routine non-medical infant circumcision.[137] The Royal Dutch Medical Association questions why the ethics regarding male genital alterations should be viewed any differently from female genital alterations.[29]

Economic considerations

The cost-effectiveness of circumcision has been studied to determine whether a policy of circumcising all newborns or a policy of promoting and providing inexpensive or free access to circumcision for all adult men who choose it would result in lower overall societal healthcare costs. As HIV/AIDS is an incurable disease that is expensive to manage, significant effort has been spent studying the cost-effectiveness of circumcision to reduce its spread in parts of Africa that have a relatively high infection rate and low circumcision prevalence.[138] Several analyses have concluded that circumcision programs for adult men in Africa are cost-effective and in some cases are cost-saving.[39][139] In Rwanda, circumcision has been found to be cost-effective across a wide range of age groups from newborn to adult,[48][140] with the greatest savings achieved when the procedure is performed in the newborn period due to the lower cost per procedure and greater timeframe for HIV infection protection.[13][140] Circumcision for the prevention of HIV transmission in adults has also been found to be cost-effective in South Africa, Kenya, and Uganda, with cost savings estimated in the billions of US dollars over 20 years.[138] Hankins et al. (2011) estimated that a $1.5 billion investment in circumcision for adults in 13 high-priority African countries would yield $16.5 billion in savings.[141]

The overall cost-effectiveness of neonatal circumcision has also been studied in the United States, which has a different cost setting from Africa in areas such as public health infrastructure, availability of medications, and medical technology and the willingness to use it.[142] A study by the CDC suggests that newborn circumcision would be societally cost-effective in the United States based on circumcision's efficacy against the transmission of HIV alone during penis in vagina intercourse, without considering any other cost benefits.[3] The American Academy of Pediatrics (2012) recommends that neonatal circumcision in the United States be covered by third-party payers such as Medicaid and insurance.[3] A 2014 review that considered reported benefits of circumcision such as reduced risks from HIV, HPV, and HSV-2 stated that circumcision is cost-effective in both the United States and Africa and may result in health care savings.[143] However, a 2014 literature review found that there are significant gaps in the current literature on male and female sexual health that need to be addressed for the literature to be applicable to North American populations.[82]

References

- Rudolph C, Rudolph A, Lister G, First L, Gershon A (18 March 2011). Rudolph's Pediatrics, 22nd Edition. McGraw-Hill Companies, Incorporated. p. 188. ISBN 978-0-07-149723-7. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- Sawyer S (November 2011). Pediatric Physical Examination & Health Assessment. Jones & Bartlett Publishers. pp. 555–556. ISBN 978-1-4496-7600-1. Archived from the original on 2016-01-18.

- American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision (2012). "Technical Report". Pediatrics. 130 (3): e756–e785. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-1990. ISSN 0031-4005. PMID 22926175. Archived from the original on 2012-09-20.

- "Male circumcision: Global trends and determinants of prevalence, safety and acceptability" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2015-12-22.

- Lissauer T, Clayden G (October 2011). Illustrated Textbook of Paediatrics, Fourth edition. Elsevier. pp. 352–353. ISBN 978-0-7234-3565-5.

Although routine neonatal circumcision is still common in some Western countries such as the USA, the arguments generally used to justify on medical grounds have been discredited and no national or international medical association currently advocates routine neonatal circumcision.

- Hay W, Levin M (25 June 2012). Current Diagnosis and Treatment Pediatrics 21/E. McGraw Hill Professional. pp. 18–19. ISBN 978-0-07-177971-5. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- Jacobs, Micah; Grady, Richard; Bolnick, David A. (2012). "Current Circumcision Trends and Guidelines". In Bolnick, David A.; Koyle, Martin; Yosha, Assaf (eds.). Surgical Guide to Circumcision. London: Springer. pp. 3–8. doi:10.1007/978-1-4471-2858-8_1. ISBN 978-1-4471-2857-1.

Outside of strategic regions in sub-Saharan Africa, no call for routine circumcision has been made by any established medical organizations or governmental bodies. Positions on circumcision include "some medical benefit/parental choice" in the United States, "no medical benefit/parental choice" in Great Britain, and "no medical benefit/physical and psychological trauma/parental choice" in the Netherlands.

- Pinto K (August 2012). "Circumcision controversies". Pediatric Clinics of North America. 59 (4): 977–986. doi:10.1016/j.pcl.2012.05.015. PMID 22857844.

- Caga-anan EC, Thomas AJ, Diekema DS, Mercurio MR, Adam MR (8 September 2011). Clinical Ethics in Pediatrics: A Case-Based Textbook. Cambridge University Press. p. 43. ISBN 978-0-521-17361-2. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- Krieger JN (May 2011). "Male circumcision and HIV infection risk". World Journal of Urology. 30 (1): 3–13. doi:10.1007/s00345-011-0696-x. PMID 21590467.

- Siegfried, N; Muller, M; Deeks, JJ; Volmink, J (2009). Siegfried, Nandi (ed.). "Male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews (2): CD003362. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD003362.pub2. PMID 19370585.

- "WHO and UNAIDS announce recommendations from expert consultation on male circumcision for HIV prevention". World Health Organization. March 2007. Archived from the original on 2013-03-12.

- Kim, Howard H; Li, Philip S; Goldstein, Marc (November 2010). "Male circumcision: Africa and beyond?". Current Opinion in Urology. 20 (6): 515–9. doi:10.1097/MOU.0b013e32833f1b21. PMID 20844437. S2CID 2158164.

- Sharma, SC; Raison, N; Khan, S; Shabbir, M; Dasgupta, P; Ahmed, K (12 December 2017). "Male Circumcision for the Prevention of HIV Acquisition: A Meta-Analysis". BJU International. 121 (4): 515–526. doi:10.1111/bju.14102. PMID 29232046.

- Larke N, Thomas SL, Dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA (November 2011). "Male circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis". J. Infect. Dis. 204 (9): 1375–90. doi:10.1093/infdis/jir523. PMID 21965090.

- Rehmeyer C, CJ (2011). "Male Circumcision and Human Papillomavirus Studies Reviewed by Infection Stage and Virus Type". J Am Osteopath Assoc. 111 (3 suppl 2): S11–S18. PMID 21415373.

- Yuan, Tanwei; Fitzpatrick, Thomas; Ko, Nai-Ying; Cai, Yong; Chen, Yingqing; Zhao, Jin; Li, Linghua; Xu, Junjie; Gu, Jing (April 2019). "Circumcision to prevent HIV and other sexually transmitted infections in men who have sex with men: a systematic review and meta-analysis of global data". The Lancet Global Health. 7 (4): e436–e447. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30567-9. ISSN 2214-109X. PMID 30879508.

- Weiss, HA; Larke, N; Halperin, D; Schenker, I (2010). "Complications of circumcision in male neonates, infants and children: a systematic review". BMC Urol. 10: 2. doi:10.1186/1471-2490-10-2. PMC 2835667. PMID 20158883.

- Selekman, Rachel; Copp, Hillary (2020). "Urologic Evaluation of the Child". In Partin, Alan (ed.). Campbell Walsh Wein Urology (12th ed.). Elsevier. pp. 388–402. ISBN 9780323672276.

- The American Academy of Pediatrics Task Force on Circumcision "Technical Report" (2012) addresses sexual function, sensitivity and satisfaction without qualification by age of circumcision. Sadeghi-Nejad et al. "Sexually transmitted diseases and sexual function" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function. Doyle et al. "The Impact of Male Circumcision on HIV Transmission" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function. Perera et al. "Safety and efficacy of nontherapeutic male circumcision: a systematic review" (2010) addresses adult circumcision and sexual function and satisfaction.

- Morris, BJ; Krieger, JN (November 2013). "Does male circumcision affect sexual function, sensitivity, or satisfaction?--a systematic review". The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 10 (11): 2644–57. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.693.6628. doi:10.1111/jsm.12293. PMID 23937309.

- "Neonatal and child male circumcision: a global review" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2010. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2016-01-18. Retrieved 12 April 2015.

- Owings, Maria. "Products - Health E Stats - Trends in Circumcision Among Male Newborns Born in U.S. Hospitals: 1979–2010". www.cdc.gov. The Centers for Disease Control. Retrieved 1 May 2019.

- Doyle D (October 2005). "Ritual male circumcision: a brief history". The Journal of the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. 35 (3): 279–285. PMID 16402509.

- Alanis MC, Lucidi RS (May 2004). "Neonatal circumcision: a review of the world's oldest and most controversial operation". Obstet Gynecol Surv. 59 (5): 379–95. doi:10.1097/00006254-200405000-00026. PMID 15097799.

- Glass JM (January 1999). "Religious circumcision: a Jewish view". BJUI. 83 Suppl 1: 17–21. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1017.x. PMID 10349410.

- "Circumcision". Columbia Encyclopedia. Columbia University Press. 2011. Archived from the original on 2015-09-24.

- Clark M (10 March 2011). Islam For Dummies. John Wiley & Sons. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-118-05396-6. Archived from the original on 18 January 2016.

- "Non-therapeutic circumcision of male minors - KNMG Viewpoint". Retrieved 7 March 2018.

- "Referat bestyrelsesmøde den 16. december 2013". Retrieved 4 September 2016.

- Marrazzo, JM; del Rio, C; Holtgrave, DR; Cohen, MS; Kalichman, SC; Mayer, KH; Montaner, JS; Wheeler, DP; Grant, RM; Grinsztejn, B; Kumarasamy, N; Shoptaw, S; Walensky, RP; Dabis, F; Sugarman, J; Benson, CA; International Antiviral Society-USA, Panel (Jul 23–30, 2014). "HIV prevention in clinical care settings: 2014 recommendations of the International Antiviral Society-USA Panel". JAMA: The Journal of the American Medical Association. 312 (4): 390–409. doi:10.1001/jama.2014.7999. PMC 6309682. PMID 25038358.

- "Manual for male circumcision under local anaesthesia". Geneva: World Health Organization. December 2009. Archived from the original on 2012-12-27.

- "Use of devices for adult male circumcision in public health HIV prevention programmes: Conclusions of the Technical Advisory Group on Innovations in Male Circumcision" (PDF). World Health Organization. 2012. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2013-03-12. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Perera, CL; Bridgewater, FH; Thavaneswaran, P; Maddern, GJ (2010). "Safety and efficacy of nontherapeutic male circumcision: a systematic review". Annals of Family Medicine. 8 (1): 64–72. doi:10.1370/afm.1073. PMC 2807391. PMID 20065281.

- "Professional Standards and Guidelines – Circumcision (Infant Male)". College of Physicians and Surgeons of British Columbia. September 2009. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Lonnqvist P (Sep 2010). "Regional anaesthesia and analgesia in the neonate". Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 24 (3): 309–21. doi:10.1016/j.bpa.2010.02.012. PMID 21033009.

- Shockley RA, Rickett K; Rickett (April 2011). "Clinical inquiries. What's the best way to control circumcision pain in newborns?". J Fam Pract. 60 (4): 233a–b. PMID 21472156.

- Wolter C, Dmochowski R (2008). "Circumcision". Handbook of Office Urological Procedures. Springer. pp. 88–. ISBN 978-1-84628-523-3. Archived from the original on 2016-01-18.

- Uthman, OA; Popoola, TA; Uthman, MM; Aremu, O (2010). Van Baal, Pieter H. M (ed.). "Economic evaluations of adult male circumcision for prevention of heterosexual acquisition of HIV in men in sub-Saharan Africa: a systematic review". PLOS ONE. 5 (3): e9628. Bibcode:2010PLoSO...5.9628U. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0009628. PMC 2835757. PMID 20224784.

- Weiss, HA; Dickson, KE; Agot, K; Hankins, CA (2010). "Male circumcision for HIV prevention: current research and programmatic issues". AIDS. 24 Suppl 4: S61–9. doi:10.1097/01.aids.0000390708.66136.f4. PMC 4233247. PMID 21042054.

- "New Data on Male Circumcision and HIV Prevention: Policy and Programme Implications" (PDF). World Health Organization. March 28, 2007. Archived (PDF) from the original on August 8, 2007.

- Dinh MH; Fahrbach KM; Hope TJ (March 2011). "The role of the foreskin in male circumcision: an evidence-based review". Am J Reprod Immunol. 65 (3): 279–83. doi:10.1111/j.1600-0897.2010.00934.x. PMC 3091617. PMID 21114567.

- Lei, JH; Liu, LR; Wei, Q; Yan, SB; Yang, L; Song, TR; Yuan, HC; Lv, X; Han, P (5 May 2015). "Circumcision Status and Risk of HIV Acquisition during Heterosexual Intercourse for Both Males and Females: A Meta-Analysis". PLOS ONE. 10 (5): e0125436. Bibcode:2015PLoSO..1025436L. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0125436. PMC 4420461. PMID 25942703.

- "Male Circumcision and Risk for HIV Transmission and Other Health Conditions: Implications for the United States". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 7 February 2008. Archived from the original on 20 February 2017. Retrieved 11 March 2017.

- "STD facts – Human papillomavirus (HPV)". CDC. Archived from the original on September 11, 2012. Retrieved September 12, 2012.

- See: Larke et al. "Male circumcision and human papillomavirus infection in men: a systematic review and meta-analysis" (2011), Albero et al. "Male Circumcision and Genital Human Papillomavirus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis" (2012), Rehmeyer "Male Circumcision and Human Papillomavirus Studies Reviewed by Infection Stage and Virus Type" (2011).

- Zhu, YP; Jia, ZW; Dai, B; Ye, DW; Kong, YY; Chang, K; Wang, Y (8 March 2016). "Relationship between circumcision and human papillomavirus infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Asian Journal of Andrology. 19 (1): 125–131. doi:10.4103/1008-682X.175092. PMC 5227661. PMID 26975489.

- Albero G, Castellsagué X, Giuliano AR, Bosch FX (February 2012). "Male Circumcision and Genital Human Papillomavirus: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Sex Transm Dis. 39 (2): 104–113. doi:10.1097/OLQ.0b013e3182387abd. PMID 22249298. S2CID 26859788.

- Weiss, HA; Thomas, SL; Munabi, SK; Hayes, RJ (April 2006). "Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta‐analysis". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (2): 101–9, discussion 110. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.017442. PMC 2653870. PMID 16581731.

- Wetmore, CM; Manhart, LE; Wasserheit, JN (April 2010). "Randomized controlled trials of interventions to prevent sexually transmitted infections: learning from the past to plan for the future". Epidemiol Rev. 32 (1): 121–36. doi:10.1093/epirev/mxq010. PMC 2912604. PMID 20519264.

- Templeton, DJ; Millett, GA; Grulich, AE (February 2010). "Male circumcision to reduce the risk of HIV and sexually transmitted infections among men who have sex with men". Current Opinion in Infectious Diseases. 23 (1): 45–52. doi:10.1097/QCO.0b013e328334e54d. PMID 19935420.

- Hayashi, Y; Kojima, Y; Mizuno, K; Kohri, K (3 February 2011). "Prepuce: phimosis, paraphimosis, and circumcision". TheScientificWorldJournal. 11: 289–301. doi:10.1100/tsw.2011.31. PMC 5719994. PMID 21298220.

- Becker K (January 2011). "Lichen sclerosus in boys". Deutsches Ärzteblatt International. 108 (4): 53–8. doi:10.3238/arztebl.2011.0053. PMC 3036008. PMID 21307992.

- Moreno, G; Corbalán, J; Peñaloza, B; Pantoja, T (2 September 2014). "Topical corticosteroids for treating phimosis in boys". The Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 9 (9): CD008973. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD008973.pub2. PMID 25180668.

- Celis, S; Reed, F; Murphy, F; Adams, S; Gillick, J; Abdelhafeez, AH; Lopez, PJ (February 2014). "Balanitis xerotica obliterans in children and adolescents: a literature review and clinical series". Journal of Pediatric Urology. 10 (1): 34–9. doi:10.1016/j.jpurol.2013.09.027. PMID 24295833.

- Krill, Aaron; Palmer, Lane; Palmer, Jeffrey (2011). "Complications of Circumcision". ScientificWorldJournal. 11: 2458–68. doi:10.1100/2011/373829. PMC 3253617. PMID 22235177.

- Leber M, Tirumani A (June 8, 2006). "Balanitis". EMedicine. Archived from the original on October 7, 2008. Retrieved 2008-10-14.

- Osipov V, Acker S (November 2006). "Balanoposthitis". Reactive and Inflammatory Dermatoses. EMedicine. Archived from the original on 2006-12-11. Retrieved 2006-11-20.

- Aridogan IA, Izol V, Ilkit M (August 2011). "Superficial fungal infections of the male genitalia: a review". Crit. Rev. Microbiol. 37 (3): 237–44. doi:10.3109/1040841X.2011.572862. PMID 21668404.

- Hayashi Y, Kojima Y, Mizuno K, Kohri K (2011). "Prepuce: phimosis, paraphimosis, and circumcision". ScientificWorldJournal. 11: 289–301. doi:10.1100/tsw.2011.31. PMC 5719994. PMID 21298220.

- Morris, Brian J.; Wiswell, Thomas E. (2013). "Circumcision and Lifetime Risk of Urinary Tract Infection: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". The Journal of Urology. 189 (6): 2118–2124. doi:10.1016/j.juro.2012.11.114. ISSN 0022-5347. PMID 23201382.

- Jagannath, VA; Fedorowicz, Z; Sud, V; Verma, AK; Hajebrahimi, S (2012). Fedorowicz, Zbys (ed.). "Routine neonatal circumcision for the prevention of urinary tract infections in infancy". Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews. 11 (5): CD009129.pub2. doi:10.1002/14651858.CD009129.pub2. PMID 23152269.

- Larke NL, Thomas SL, Dos Santos Silva I, Weiss HA (August 2011). "Male circumcision and penile cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Cancer Causes Control. 22 (8): 1097–110. doi:10.1007/s10552-011-9785-9. PMC 3139859. PMID 21695385.

- Bleeker, M. C. G.; Heideman, D. A. M.; Snijders, P. J. F.; Horenblas, S.; Dillner, J.; Meijer, C. J. L. M. (2008). "Penile cancer: Epidemiology, pathogenesis and prevention". World Journal of Urology. 27 (2): 141–150. doi:10.1007/s00345-008-0302-z. PMID 18607597.

- Pow-Sang, M. R.; Ferreira, U.; Pow-Sang, J. M.; Nardi, A. C.; Destefano, V. (2010). "Epidemiology and Natural History of Penile Cancer". Urology. 76 (2): S2–S6. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2010.03.003. PMID 20691882.

- "Can penile cancer be prevented?". Learn About Cancer: Penile Cancer: Detailed Guide. American Cancer Society. Archived from the original on 2017-03-12. Retrieved 2017-03-11.

- Pabalan, N; Singian, E; Jarjanazi, H; Paganini-Hill, A (December 2015). "Association of male circumcision with risk of prostate cancer: a meta-analysis". Prostate Cancer and Prostatic Diseases. 18 (4): 352–7. doi:10.1038/pcan.2015.34. PMID 26215783.

- Li, YD; Teng, Y; Dai, Y; Ding, H (2016). "The Association of Circumcision and Prostate Cancer: A Meta-Analysis". Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 17 (8): 3823–7. PMID 27644623. Archived from the original on 2017-02-23.

- Grund, Jonathan M.; Bryant, Tyler S.; Jackson, Inimfon; Curran, Kelly; Bock, Naomi; Toledo, Carlos; Taliano, Joanna; Zhou, Sheng; Del Campo, Jorge Martin (November 2017). "Association between male circumcision and women's biomedical health outcomes: a systematic review". The Lancet. Global Health. 5 (11): e1113–e1122. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(17)30369-8. ISSN 2214-109X. PMC 5728090. PMID 29025633.

- American Urological Association. "Circumcision". Archived from the original on 2013-08-25. Retrieved 2008-11-02.

- Krill, Aaron J.; Palmer, Lane S.; Palmer, Jeffrey S. (2011). "Complications of Circumcision". The Scientific World Journal. 11: 2458–2468. doi:10.1100/2011/373829. ISSN 1537-744X. PMC 3253617. PMID 22235177.

- "Neonatal Circumcision". American Academy of Family Physicians. 2013. Archived from the original on 2015-07-21. Retrieved 2015-08-03.

- Krill, AJ; Palmer, LS; Palmer, JS (2011). "Complications of circumcision". TheScientificWorldJournal. 11: 2458–68. doi:10.1100/2011/373829. PMC 3253617. PMID 22235177.

- Morris, Brian J.; Krieger, John N. (2017-08-04). "Does Circumcision Increase Meatal Stenosis Risk? – a Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis". Urology. 110: 16–26. doi:10.1016/j.urology.2017.07.027. ISSN 1527-9995. PMID 28826876.

Weak evidence suggests that MS risk might be higher in circumcised boys and young adult males.

- Canadian Paediatric Society (Sep 8, 2015). "Newborn male circumcision Position statements and practice points". Paediatr Child Health. 20 (6): 311–15. doi:10.1093/pch/20.6.311. PMC 4578472. PMID 26435672. Archived from the original on 2016-01-18.

- "Circumcision in men". National Health Service. 22 February 2016.

- Dave S, Afshar K, Braga LH, Anderson P (February 2018). "Canadian Urological Association guideline on the care of the normal foreskin and neonatal circumcision in Canadian infants (full version)". Can Urol Assoc J. 12 (2): E76–E99. doi:10.5489/cuaj.5033. PMC 5937400. PMID 29381458.

- Shabanzadeh DM, Düring S, Frimodt-Møller C (July 2016). "Male circumcision does not result in inferior perceived male sexual function - a systematic review". Dan Med J (Systematic review). 63 (7). PMID 27399981.

- Friedman, B; Khoury, J; Petersiel, N; Yahalomi, T; Paul, M; Neuberger, A (4 August 2016). "Pros and cons of circumcision: an evidence-based overview". Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 22 (9): 768–774. doi:10.1016/j.cmi.2016.07.030. PMID 27497811.

- Tian Y, Liu W, Wang JZ, Wazir R, Yue X, Wang KJ (2013). "Effects of circumcision on male sexual functions: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Asian J. Androl. (Systematic review). 15 (5): 662–6. doi:10.1038/aja.2013.47. PMC 3881635. PMID 23749001.

- Yang, Y; Wang, X; Bai, Y; Han, P (27 June 2017). "Circumcision does not have effect on premature ejaculation: A systematic review and meta-analysis". Andrologia. 50 (2): e12851. doi:10.1111/and.12851. PMID 28653427.

- Bossio JA, Pukall CF, Steele S (2014). "A review of the current state of the male circumcision literature". J. Sex. Med. 11 (12): 2847–64. doi:10.1111/jsm.12703. PMID 25284631.

- "Non-therapeutic male circumcision (NTMC) of children – practical guidance for doctors" (pdf). British Medical Association. 2019.

- Morris BJ, Moreton S, Krieger JN (November 2019). "Critical evaluation of arguments opposing male circumcision: A systematic review". J Evid Based Med (Systematic review). 12 (4): 263–290. doi:10.1111/jebm.12361. PMC 6899915. PMID 31496128.

- Morris, Brian J; Wamai, Richard G; Henebeng, Esther B; Tobian, Aaron AR; Klausner, Jeffrey D; Banerjee, Joya; Hankins, Catherine A (1 March 2016). "Estimation of country-specific and global prevalence of male circumcision". Population Health Metrics. 14 (1): 4. doi:10.1186/s12963-016-0073-5. PMC 4772313. PMID 26933388.

- Drain PK, Halperin DT, Hughes JP, Klausner JD, Bailey RC (2006). "Male circumcision, religion, and infectious diseases: an ecologic analysis of 118 developing countries". BMC Infectious Diseases. 6: 172. doi:10.1186/1471-2334-6-172. PMC 1764746. PMID 17137513.

- Klavs I, Hamers FF (February 2008). "Male circumcision in Slovenia: results from a national probability sample survey". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 84 (1): 49–50. doi:10.1136/sti.2007.027524. PMID 17881413.

- Ko MC, Liu CK, Lee WK, Jeng HS, Chiang HS, Li CY (April 2007). "Age-specific prevalence rates of phimosis and circumcision in Taiwanese boys". Journal of the Formosan Medical Association=Taiwan Yi Zhi. 106 (4): 302–7. doi:10.1016/S0929-6646(09)60256-4. PMID 17475607.

- Richters, J; Smith, AM; De Visser, RO; Grulich, AE; Rissel, CE (August 2006). "Circumcision in Australia: prevalence and effects on sexual health". Int J STD AIDS. 17 (8): 547–54. doi:10.1258/095646206778145730. PMID 16925903.

- Owings M, et al. (August 22, 2013). "Trends in Circumcision for Male Newborns in U.S. Hospitals: 1979–2010". Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Archived from the original on 23 January 2014. Retrieved 22 January 2014.

- Gollaher (2001), ch. 1, The Jewish Tradition, pp. 1–30

- McNutt, Paula M. (1999). Reconstructing the Society of Ancient Israel. Westminster John Knox Press. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-664-22265-9.

Abraham patriarchal known history.

CS1 maint: ref=harv (link) - "Circumcision". Encyclopaedia Judaica (2 ed.). USA: Macmillan Reference. 2006. ISBN 978-0-02-865928-2.

- Hirsch, Emil G; Kohler, Kaufmann; Jacobs, Joseph; Friedenwald, Aaron; Broydé, Isaac (1906). "Circumcision". Jewish Encyclopedia.

In order to prevent the obliteration of the 'seal of the covenant' on the flesh, as circumcision was henceforth called, the Rabbis, probably after the war of Bar Kokba (see Yeb. l.c.; Gen. R. xlvi.), instituted the 'peri'ah' (the laying bare of the glans), without which circumcision was declared to be of no value (Shab. xxx. 6).

- Gollaher (2001), ch. 2, Christians and Muslims, pp. 31–52

- Donald Daniel Leslie (1998). "The Integration of Religious Minorities in China: The Case of Chinese Muslims" (PDF). The Fifty-ninth George Ernest Morrison Lecture in Ethnology. p. 12. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2010. Retrieved 30 November 2010.

- Johan Elverskog (2010). Buddhism and Islam on the Silk Road (illustrated ed.). University of Pennsylvania Press. pp. 228. ISBN 978-0-8122-4237-9. Retrieved 2010-06-28.

halal chinggis khan you are our slaves .

- Gollaher (2001), ch. 3, Symbolic Wounds, pp. 53–72

- Darby, Robert (Spring 2003). "The Masturbation Taboo and the Rise of Routine Male Circumcision: A Review of the Historiography". Journal of Social History. 36 (3): 737–757. doi:10.1353/jsh.2003.0047.

- Gollaher (2001), ch. 4, From Ritual to Science, pp. 73–108

- Bullough, Vern L.; Bonnie Bullough (1994). Human Sexuality: An Encyclopedia. New York: Garland. p. 425. ISBN 978-0824079727.

- Conrad, Peter; Joseph W. Schneider (1992). Deviance and Medicalization: From Badness to Sickness. Philadelphia: Temple University Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0877229995.

- Darby, Robert (2005). A surgical temptation : the demonization of the foreskin and the rise of circumcision in Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. pp. 262–. ISBN 978-0-226-13645-5.

- Matthew, H. C. G. (2004). Oxford dictionary of national biography : in association with the British Academy : from the earliest times to the year 2000. Oxford New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-861411-1.

- Gollaher 2001, p. 106

- Gairdner D (1949). "The fate of the foreskin: a study of circumcision". Br Med J. 2 (4642): 1433–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1433. PMC 2051968. PMID 15408299.

- Boyle GJ, Hill G (2011). "Sub-Saharan African randomised clinical trials into male circumcision and HIV transmission: methodological, ethical and legal concerns". J Law Med. 19 (2): 316–34. PMID 22320006.

- Dowsett GW, Couch M (May 2007). "Male circumcision and HIV prevention: is there really enough of the right kind of evidence?". Reproductive Health Matters. 15 (29): 33–44. doi:10.1016/S0968-8080(07)29302-4. PMID 17512372.

- Darby R, Van Howe R (2011). "Not a surgical vaccine: there is no case for boosting infant male circumcision to combat heterosexual transmission of HIV in Australia". Australian and New Zealand Journal of Public Health. 35 (5): 459–465. doi:10.1111/j.1753-6405.2011.00761.x. PMID 21973253.

- Frisch M; et al. (2013). "Cultural Bias in the AAP's 2012 Technical Report and Policy Statement on Male Circumcision". Pediatrics. 131 (4): 796–800. doi:10.1542/peds.2012-2896. PMID 23509170.