History of circumcision

Circumcision has ancient roots among several ethnic groups in sub-equatorial Africa, and is still performed on adolescent boys to symbolize their transition to warrior status or adulthood.[1] Circumcision and/or subincision, often as part of an intricate coming of age ritual, was a common practice among Australian Aborigines and Pacific islanders at first contact with Western travellers. It is still practiced in the traditional way by a proportion of the population.[2][3]

In Judaism, circumcision has traditionally been practised among males on the eighth day after birth. The Book of Genesis records circumcision as part of the Abrahamic covenant with Yahweh (God). Circumcision was common, although not universal, among ancient Semitic people. Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, lists the Colchians, Ethiopians, Phoenicians, and Syrians as circumcising cultures. In the aftermath of the conquests of Alexander the Great, however, Greek dislike of circumcision (they regarded a man as truly "naked" only if his prepuce was retracted) led to a decline in its incidence among many peoples that had previously practiced it. The writer of 1 Maccabees wrote that under the Seleucids, many Jewish men attempted to hide or reverse their circumcision so they could exercise in Greek gymnasia, where nudity was the norm. First Maccabees also relates that the Seleucids forbade the practice of brit milah (Jewish circumcision), and punished those who performed it, as well as the infants who underwent it, with death.

According to “National Hospital Discharge Survey” in United States, as of 2008, the rate of circumcision of infant boys in hospitals in United States was 55.9%.[4]

Origins

The origin of circumcision is not known with certainty. It has been variously proposed that it began

- as a religious sacrifice;

- as a rite of passage marking a boy's entrance into adulthood;

- as a form of sympathetic magic to ensure virility or fertility;

- as a means of reducing sexual pleasure;

- as an aid to hygiene where regular bathing was impractical;

- as a means of marking those of higher social status;

- as a means of humiliating enemies and slaves by symbolic castration;

- as a means of differentiating a circumcising group from their non-circumcising neighbors;

- as a means of discouraging masturbation or other socially proscribed sexual behaviors;

- as a means of increasing a man's attractiveness to women;

- as a demonstration of one's ability to endure pain;

- as a male counterpart to menstruation or the breaking of the hymen;

- to copy the rare natural occurrence of a missing foreskin of an important leader;[5][6]

- as a way to repel demonesses;[7] and/or

- as a display of disgust of the smegma produced by the foreskin.

Removing the foreskin can prevent or treat a medical condition known as phimosis. It has been suggested that the custom of circumcision gave advantages to tribes that practiced it and thus led to its spread.[8][9][10]

Darby describes these theories as "conflicting", and states that "the only point of agreement among proponents of the various theories is that promoting good health had nothing to do with it."[9][11] Immerman et al. suggest that circumcision causes lowered sexual arousal of pubescent males, and hypothesize that this was a competitive advantage to tribes practising circumcision, leading to its spread.[12] Wilson suggests that circumcision reduces insemination efficiency, reducing a man's capacity for extra-pair fertilizations by impairing sperm competition. Thus, men who display this signal of sexual obedience may gain social benefits if married men are selected to offer social trust and investment preferentially to peers who are less threatening to their paternity.[13] Freud believed that circumcision allows senior men to constrain the incestuous desires of their juniors, and mediates the tension inherent in the father-son relationship and generational succession. Youth are symbolically castrated, or feminized, but also blessed with masculine fruitfulness.[14] It is possible that circumcision arose independently in different cultures for different reasons.

Africa

"The distribution of circumcision and initiation rites throughout Africa, and the frequent resemblance between details of ceremonial procedure in areas thousands of miles apart, indicate that the circumcision ritual has an old tradition behind it and in its present form is the result of a long process of development."[15]

African cultural history is conveniently spoken of in terms of language group. The Niger–Congo speakers of today extend from Senegal to Kenya to South Africa and all points between. In the historic period, the Niger–Congo speaking peoples predominantly have and have had circumcision that occurred in young warrior initiation schools, the schools of Senegal and Gambia being not so very different from those of the Kenyan Gikuyu and South African Zulu. Their common ancestor was a horticultural group five, perhaps seven, thousand years ago from an area of the Cross River in modern Nigeria. From that area a horticultural frontier moved outward into West Africa and the Congo Basin. Certainly the warrior schools with circumcision were a part of the ancestral society's cultural repertoire.[16]

Circumcision in East Africa is a rite of passage from childhood to adulthood, but is only practiced in some nations (tribes). Some peoples in East Africa do not practice circumcision (for example the Luo of western Kenya).[16]

Amongst the Gikuyu (Kikuyu) people of Kenya and the Maasai people of Kenya and Tanzania, circumcision has historically been the graduation element of an educational program that taught tribal beliefs, practices, culture, religion and history to youth who were on the verge of becoming full-fledged members of society. The circumcision ceremony was very public, and required a display of courage under the knife in order to maintain the honor and prestige of the young man and his family. The only form of anesthesia was a bath in the cold morning waters of a river, which tended to numb the senses to a minor degree. The youths being circumcised were required to maintain a stoic expression and not to flinch from the pain.[16]

After circumcision, young men became members of the warrior class, and were free to date and marry. The graduants became a fraternity that served together, and continued to have mutual obligation to each other for life.

In the modern context in East Africa, the physical element of circumcision remains (in the societies that have historically practiced it) but without most of the other accompanying rites, context and programs. For many, the operation is now performed in private on one individual, in a hospital or doctor's office. Anesthesia is often used in such settings. There are tribes however, that do not accept this modernized practice. They insist on circumcision in a group ceremony, and a test of courage at the banks of a river. This more traditional approach is common amongst the Meru and the Kisii tribes of Kenya.[16]

Despite the loss of the rites and ceremonies that accompanied circumcision in the past, the physical operation remains crucial to personal identity and pride, and acceptance in society. Uncircumcised men in these communities risk being "outed", and subjected to ridicule as "boys". There have been many cases of forced circumcision of men from such communities who are discovered to have escaped the ritual.

In some South African ethnic groups, circumcision has roots in several belief systems, and is performed most of the time on teenage boys:

The young men in the eastern Cape belong to the Xhosa ethnic group for whom circumcision is considered part of the passage into manhood. ... A law was recently introduced requiring initiation schools to be licensed and only allowing circumcisions to be performed on youths aged 18 and older. But Eastern Cape provincial Health Department spokesman Sizwe Kupelo told Reuters news agency that boys as young as 11 had died. Each year thousands of young men go into the bush alone, without water, to attend initiation schools. Many do not survive the ordeal.[17]

Ancient world

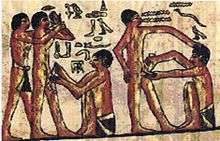

Sixth Dynasty (2345–2181 BCE) tomb artwork in Egypt has been thought to be the oldest documentary evidence of circumcision, the most ancient depiction being a bas-relief from the necropolis at Saqqara (c. 2400 BCE) with the inscriptions reading: "The ointment is to make it acceptable." and "Hold him so that he does not fall". In the oldest written account, by an Egyptian named Uha, in the 23rd century BCE, he describes a mass circumcision and boasts of his ability to stoically endure the pain: "When I was circumcised, together with one hundred and twenty men ... there was none thereof who hit out, there was none thereof who was hit, and there was none thereof who scratched and there was none thereof who was scratched."[18]

Herodotus, writing in the 5th century BCE, wrote that the Egyptians "practise circumcision for the sake of cleanliness, considering it better to be cleanly than comely."[19] David Gollaher[20] considered circumcision in ancient Egypt to be a mark of passage from childhood to adulthood. He mentions that the alteration of the body and ritual of circumcision were supposed to give access to ancient mysteries reserved solely for the initiated. (See also Clement of Alexandria, Stromateis 1.15) The content of those mysteries are unclear but are likely to be myths, prayers, and incantations central to Egyptian religion. The Egyptian Book of the Dead, for example, tells of the sun god Ra cutting himself, the blood creating two minor guardian deities. The Egyptologist Emmanuel vicomte de Rougé interpreted this as an act of circumcision.[21] Circumcisions were performed by priests in a public ceremony, using a stone blade. It is thought to have been more popular among the upper echelons of the society, although it was not universal and those lower down the social order are known to have had the procedure done.[22] The Egyptian hieroglyph for "penis" depicts either a circumcised or an erect organ.

Circumcision was also adopted by some Semitic peoples living in or around Egypt. Herodotus reported that circumcision is only practiced by the Egyptians, Colchians, Ethiopians, Phoenicians, the 'Syrians of Palestine', and "the Syrians who dwell about the rivers Thermodon and Parthenius, as well as their neighbours the Macronians and Macrones". He also reports, however, that "the Phoenicians, when they come to have commerce with the Greeks, cease to follow the Egyptians in this custom, and allow their children to remain uncircumcised."[19]

According to Genesis, God told Abraham to circumcise himself, his household and his slaves as an everlasting covenant in their flesh, see also Abrahamic Covenant. Those who were not circumcised were to be "cut off" from their people. [Genesis 17:10–14] Covenants in biblical times were often sealed by severing an animal, with the implication that the party who breaks the covenant will suffer a similar fate. In Hebrew, kārat berît meaning to seal a covenant translates literally as "cut a covenant".[23][24] It is presumed by Jewish scholars that the removal of the foreskin symbolically represents such a sealing of the covenant.[25] Moses might not have been circumcised; one of his sons was not, nor were some of his followers while traveling through the desert.[Joshua 5:4–7]. Moses's wife Zipporah circumcised their son when God threatened to kill Moses.[Exodus 4:24–26]

Hellenistic and Judaic culture

According to Hodges, ancient Greek aesthetics of the human form considered circumcision a mutilation of a previously perfectly shaped organ. Greek artwork of the period portrayed penises as covered by the foreskin (sometimes in exquisite detail), except in the portrayal of satyrs, lechers, and barbarians.[26] This dislike of the appearance of the circumcised penis led to a decline in the incidence of circumcision among many peoples that had previously practiced it throughout Hellenistic times.

In Egypt, only the priestly caste retained circumcision, and by the 2nd century, the only circumcising groups in the Roman Empire were Jews, Jewish Christians, Egyptian priests, and the Nabatean Arabs. Circumcision was sufficiently rare among non-Jews that being circumcised was considered conclusive evidence of Judaism (or Early Christianity and others derogatorily called Judaizers) in Roman courts—Suetonius in Domitian 12.2 described a court proceeding in which a ninety-year-old man was stripped naked before the court to determine whether he was evading the head tax placed on Jews and Judaizers.[27]

Cultural pressures to circumcise operated throughout the Hellenistic world: when the Judean king John Hyrcanus conquered the Idumeans, he forced them to become circumcised and convert to Judaism, but their ancestors the Edomites had practiced circumcision in pre-Hellenistic times.

Some Jews tried to hide their circumcision status, as told in 1 Maccabees. This was mainly for social and economic benefits and also so that they could exercise in gymnasiums and compete in sporting events. Techniques for restoring the appearance of an uncircumcised penis were known by the 2nd century BCE. In one such technique, a copper weight (called the Judeum pondum) was hung from the remnants of the circumcised foreskin until, in time, they became sufficiently stretched to cover the glans. The 1st-century writer Celsus described two surgical techniques for foreskin restoration in his medical treatise De Medicina.[28] In one of these, the skin of the penile shaft was loosened by cutting in around the base of the glans. The skin was then stretched over the glans and allowed to heal, giving the appearance of an uncircumcised penis. This was possible because the Abrahamic covenant of circumcision defined in the Bible was a relatively minor circumcision; named milah, this involved cutting off the foreskin that extended beyond the glans. Jewish religious writers denounced such practices as abrogating the covenant of Abraham in 1 Maccabees and the Talmud.[29]

Later during the Talmudic period (500–625 CE) a third step, known as Metzitzah, began to be practiced. In this step the mohel would suck the blood from the circumcision wound with his mouth to remove what was believed to be bad excess blood. As it actually increases the likelihood of infections such as tuberculosis and venereal diseases, modern day mohels use a glass tube placed over the infant's penis for suction of the blood. In many Jewish ritual circumcisions this step of Metzitzah has been eliminated.[30]

First Maccabees tells us that the Seleucids forbade the practice of brit milah, and punished those who performed it – as well as the infants who underwent it – with death.

The 1st-century Jewish author Philo Judaeus (20 BCE - 50 CE)[31] defended Jewish circumcision on several grounds, including health, cleanliness and fertility.[32] He also thought that circumcision should be done as early as possible as it would not be as likely to be done by someone's own free will. He claimed that the foreskin prevented semen from reaching the vagina and so should be done as a way to increase the nation's population. He also noted that circumcision should be performed as an effective means to reduce sexual pleasure: "The legislators thought good to dock the organ which ministers to such intercourse thus making circumcision the symbol of excision of excessive and superfluous pleasure."[33] There was also division in Pharisaic Judaism between Hillel the Elder and Shammai on the issue of circumcision of proselytes.

The Jewish philosopher Maimonides (1135–1204) insisted that faith should be the only reason for circumcision. He recognised that it was "a very hard thing" to have done to oneself but that it was done to "quell all the impulses of matter" and "perfect what is defective morally." Sages at the time had recognised that the foreskin heightened sexual pleasure. Maimonides reasoned that the bleeding and loss of protective covering rendered the penis weakened and in so doing had the effect of reducing a man's lustful thoughts and making sex less pleasurable. He also warned that it is "hard for a woman with whom an uncircumcised man has had sexual intercourse to separate from him."[34][35][36][37]

A 13th-century French disciple of Maimonides, Isaac ben Yediah claimed that circumcision was an effective way of reducing a woman's sexual desire. With a non-circumcised man, he said, she always orgasms first and so her sexual appetite is never fulfilled, but with a circumcised man she receives no pleasure and hardly ever orgasms "because of the great heat and fire burning in her."[38][39]

Flavius Josephus in Jewish Antiquities book 20, chapter 2 records the story of King Izates who having been persuaded by a Jewish merchant named Ananias to embrace the Jewish religion, decided to get circumcised so as to follow Jewish law. Despite being reticent for fear of reprisals from his non-Jewish subjects he was eventually persuaded to do it by a Galileean Jew named Eleazar on the grounds that it was one thing to read the Law and another thing to practice it. Despite his mother Helen and Ananias's fear of the consequences, Josephus said that God looked after Izates and his reign was peaceful and blessed.[40]

Decline in Christianity

The Council of Jerusalem in Acts of the Apostles 15 addressed the issue of whether circumcision was required of new converts to Christianity. Both Simon Peter and James the Just spoke against requiring circumcision in Gentile converts and the Council ruled that circumcision was not necessary. However, Acts 16 and many references in the Letters of Paul show that the practice was not immediately eliminated. Paul of Tarsus, who was said to be directly responsible for one man's circumcision in Acts 16:1–3 and who appeared to praise Jewish circumcision in Romans 3:2, said that circumcision didn't matter in 1 Corinthians 7:19 and then increasingly turned against the practice, accusing those who promoted circumcision of wanting to make a good showing in the flesh and boasting or glorying in the flesh in Galatians 6:11–13. In a later letter, Philippians 3:2, he is reported as warning Christians to beware the "mutilation" (Strong's G2699). Circumcision was so closely associated with Jewish men that Jewish Christians were referred to as "those of the circumcision" (e.g. Colossians 3:20) [41] or conversely Christians who were circumcised were referred to as Jewish Christians or Judaizers. These terms (circumcised/uncircumcised) are generally interpreted to mean Jews and Greeks, who were predominant; however, it is an oversimplification as 1st-century Iudaea Province also had some Jews who no longer circumcised, and some Greeks (called Proselytes or Judaizers) and others such as Egyptians, Ethiopians, and Arabs who did. According to the Gospel of Thomas saying 53, Jesus says:

- "His disciples said to him, "is circumcision useful or not?" He said to them, "If it were useful, their father would produce children already circumcised from their mother. Rather, the true circumcision in spirit has become profitable in every respect."" SV [42]

Parallels to Thomas 53 are found in Paul's Romans 2:29, Philippians 3:3, 1 Corinthians 7:19, Galatians 6:15, Colossians 2:11–12.

In John's Gospel 7:23 Jesus is reported as giving this response to those who criticized him for healing on the Sabbath:

- Now if a man can be circumcised on the sabbath so that the Law of Moses is not broken, why are you angry with me for making a man whole and complete on a sabbath? ( Jerusalem Bible)

This passage has been seen as a comment on the Rabbinic belief that circumcision heals the penis (Jerusalem Bible, note to John 7:23) or as a criticism of circumcision.[41]

Europeans, with the exception of the Jews, did not practice circumcision. A rare exception occurred in Visigothic Spain, where during the armed campaign king Wamba ordered circumcision of everyone who committed atrocities against the civilian population.[43]

As part of an attempted reconciliation of Coptic and Catholic practices, the Catholic Church condemned the observance of circumcision as a moral sin and ordered against its practice in the Council of Basel-Florence in 1442.[44] According to UNAIDS, the papal bull of Union with The Copts issued during that council stated that circumcision was merely unnecessary for Christians;[45] El-Hout and Khauli, however, regard it as condemnation of the procedure.[46]

In the 18th century, Edward Gibbon referred to circumcision as a "singular mutilation" practised only by Jews and Turks and as "a painful and often dangerous rite" ... (R. Darby)[47]

In 1753 in London there was a proposal for Jewish emancipation. It was furiously opposed by the pamphleteers of the time, who spread the fear that Jewish emancipation meant universal circumcision. Men were urged to protect:

- "the best of Your property" and guard their threatened foreskins(!). It was an extraordinary outpouring of popular beliefs about sex, fears about masculinity and misconceptions about Jews, but also a striking indication of how central to their sexual identity men considered their foreskins at that time. (R.Darby)[47]

These negative attitudes remained well into the 19th century. English explorer Sir Richard Burton observed that "Christendom practically holds circumcision in horror".

Revival in the English-speaking world

Although negative attitudes prevailed for much of the 19th century, this began to change in the latter part of the century, especially in the English-speaking world. This shift can be seen in the account on circumcision in the Encyclopædia Britannica. The ninth edition, published in 1876, discusses the practice as a religious rite among Jews, Muslims, the ancient Egyptians and tribal peoples in various parts of the world. The author of the entry rejected sanitary explanations of the procedure in favour of a religious one: "like other body mutilations ... [it is] of the nature of a representative sacrifice". (R. Darby)[47]

However, by 1910 the entry [in the Encyclopædia Britannica] had been turned on its head:

"This surgical operation, which is commonly prescribed for purely medical reasons, is also an initiation or religious ceremony among Jews and Muslims".

Now it was primarily a medical procedure and only after that a religious ritual. The entry explained that "in recent years the medical profession has been responsible for its considerable extension among other than Jewish children ... for reasons of health" (11th edition, Vol. 6).

By 1929 the entry is much reduced in size and consists merely of a brief description of the operation, which is "done as a preventive measure in the infant" and "performed chiefly for purposes of cleanliness". Ironically, readers are then referred to the entries for "Mutilation" and "Deformation" for a discussion of circumcision in its religious context (14th edition, 1929, Vol. 5). (R. Darby)[47]

There were two related concerns that led to the widespread adoption of this surgical procedure at this time. The first was a growing belief within the medical community regarding the efficacy of circumcision in reducing the risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, such as syphilis. The second was the notion that circumcision would lessen the urge towards masturbation, or "self abuse" as it was often called.

The tradition of circumcision is said to have been practiced within the British Royal Family, with varying accounts regarding which monarch started it: either Queen Victoria on account of her rumored adherence to British Israelism and the notion she was a descendant of King David (or on the advice of her personal physician), or her grandfather King George.[48] The German-born King George was also the Prince-Elector of Hanover, and rumors existed that the Prince electors were circumcised.[48] This is highly dubious since there is no evidence that Victoria was a supporter of the British Israeli movement, and the links between the royal family and the ancient House of David were only first proposed by its followers in the 1870s, long after she bore her sons (there is also evidence lacking that her sons, particularly Edward, had circumcisions); there is also no indication that the prince electors (or George himself) were circumcised and that the king introduced it upon his arrival to Britain and his ascension to the throne in 1714.[48] If members of the royal family were circumcised, the reason was due to their embrace of a custom popular amongst the upper-classes in the late 19th and 20th centuries.[48] Prince Charles and his brothers are believed to have been circumcised (the former by a reputable rabbi and mohel), but the supposed tradition ended before the births of William and his brother Harry due to their mother Diana's objections.[48] Speculations arose in the media that William's son George may have been circumcised following his birth in 2013, but this is also highly unlikely.[48]

Medical concerns

The first medical doctor to advocate for the adoption of circumcision was the eminent English physician, Jonathan Hutchinson.[49] In 1855, he published a study in which he compared the rate of contraction of venereal disease amongst the gentile and Jewish population of London. Although his manipulation and usage of the data has since been shown to have been flawed (the protection that Jews appear to have are more likely due to cultural factors[50]), his study appeared to demonstrate that circumcised men were significantly less vulnerable to such disease.[51] (A 2006 systematic review concluded that the evidence "strongly indicates that circumcised men are at lower risk of chancroid and syphilis."[52])

Hutchinson was a notable leader in the campaign for medical circumcision for the next fifty years, publishing A plea for circumcison in the British Medical Journal (1890), where he contended that the foreskin "... constitutes a harbour for filth, and is a constant source of irritation. It conduces to masturbation, and adds to the difficulties of sexual continence. It increases the risk of syphilis in early life, and of cancer in the aged."[53] As can be seen, he was also a convert to the idea that circumcision would prevent masturbation, a great Victorian concern. In an 1893 article, On circumcision as a preventive of masturbation he wrote: "I am inclined to believe that [circumcision] may often accomplish much, both in breaking the habit [of masturbation] as an immediate result, and in diminishing the temptation to it subsequently."[54]

Nathaniel Heckford, a paediatrician at the East London Hospital for Children, wrote Circumcision as a Remedial Measure in Certain Cases of Epilepsy, Chorea, etc. (1865), in which he argued that circumcision acted as an effective remedial measure in the prevention of certain cases of epilepsy and chorea.

These increasingly common medical beliefs were even applied to females. The controversial obstetrical surgeon Isaac Baker Brown founded the London Surgical Home for Women in 1858, where he worked on advancing surgical procedures. In 1866, Baker Brown described the use of clitoridectomy, the removal of the clitoris, as a cure for several conditions, including epilepsy, catalepsy and mania, which he attributed to masturbation.[55][56] In On the Curability of Certain Forms of Insanity, Epilepsy, Catalepsy, and Hysteria in Females, he gave a 70 per cent success rate using this treatment.[56]

However, during 1866, Baker Brown began to receive negative feedback from within the medical profession from doctors who opposed the use of clitoridectomies and questioned the validity of Baker Brown's claims of success. An article appeared in The Times in December, which was favourable towards Baker Brown's work but suggested that Baker Brown had treated women of unsound mind.[56] He was also accused of performing clitoridectomies without the consent or knowledge of his patients or their families.[56] In 1867 he was expelled from the Obstetrical Society of London for carrying out the operations without consent.[57] Baker Brown's ideas were more accepted in the United States, where, from the 1860s, the operation was being used to cure hysteria, nymphomania, and in young girls what was called "rebellion" or "unfeminine aggression".

Lewis Sayre, New York orthopedic surgeon, became a prominent advocate for circumcision in America. In 1870, he examined a five-year-old boy who was unable to straighten his legs, and whose condition had so far defied treatment. Upon noting that the boy's genitals were inflamed, Sayre hypothesized that chronic irritation of the boy's foreskin had paralyzed his knees via reflex neurosis. Sayre circumcised the boy, and within a few weeks, he recovered from his paralysis. After several additional incidents in which circumcision also appeared effective in treating paralyzed joints, Sayre began to promote circumcision as a powerful orthopedic remedy. Sayre's prominence within the medical profession allowed him to reach a wide audience.

As more practitioners tried circumcision as a treatment for otherwise intractable medical conditions, sometimes achieving positive results, the list of ailments reputed to be treatable through circumcision grew. By the 1890s, hernia, bladder infections, kidney stones, insomnia, chronic indigestion, rheumatism, epilepsy, asthma, bedwetting, Bright's disease, erectile dysfunction, syphilis, insanity, and skin cancer had all been linked to the foreskin, and many physicians advocated universal circumcision as a preventive health measure.

Specific medical arguments aside, several hypotheses have been raised in explaining the public's acceptance of infant circumcision as preventive medicine. The success of the germ theory of disease had not only enabled physicians to combat many of the postoperative complications of surgery, but had made the wider public deeply suspicious of dirt and bodily secretions. Accordingly, the smegma that collects under the foreskin was viewed as unhealthy, and circumcision readily accepted as good penile hygiene.[58] Secondly, moral sentiment of the day regarded masturbation as not only sinful, but also physically and mentally unhealthy, stimulating the foreskin to produce the host of maladies of which it was suspected. In this climate, circumcision could be employed as a means of discouraging masturbation.[59] All About the Baby, a popular parenting book of the 1890s, recommended infant circumcision for precisely this purpose. (However, a survey of 1410 men in the United States in 1992, Laumann found that circumcised men were more likely to report masturbating at least once a month.) As hospitals proliferated in urban areas, childbirth, at least among the upper and middle classes, was increasingly under the care of physicians in hospitals rather than with midwives in the home. It has been suggested that once a critical mass of infants were being circumcised in the hospital, circumcision became a class marker of those wealthy enough to afford a hospital birth.[60]

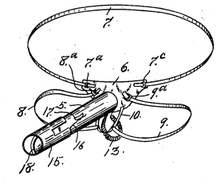

During the same time period, circumcision was becoming easier to perform. William Stewart Halsted's 1885 discovery of hypodermic cocaine as a local anaesthetic made it easier for doctors without expertise in the use of chloroform and other general anaesthetics to perform minor surgeries. Also, several mechanically aided circumcision techniques, forerunners of modern clamp-based circumcision methods, were first published in the medical literature of the 1890s, allowing surgeons to perform circumcisions more safely and successfully.

By the 1920s, advances in the understanding of disease had undermined much of the original medical basis for preventive circumcision. Doctors continued to promote it, however, as good penile hygiene and as a preventive for a handful of conditions local to the penis: balanitis, phimosis, and penile cancer.

Masturbation concerns

Circumcision in English-speaking countries arose in a climate of negative attitudes towards sex, especially concerning masturbation. In her 1978 article The Ritual of Circumcision,[59] Karen Erickson Paige writes: "The current medical rationale for circumcision developed after the operation was in wide practice. The original reason for the surgical removal of the foreskin, or prepuce, was to control 'masturbatory insanity' – the range of mental disorders that people believed were caused by the 'polluting' practice of 'self-abuse.'"

"Self-abuse" was a term commonly used to describe masturbation in the 19th century. According to Paige, "treatments ranged from diet, moral exhortations, hydrotherapy, and marriage, to such drastic measures as surgery, physical restraints, frights, and punishment. Some doctors recommended covering the penis with plaster of Paris, leather, or rubber; cauterization; making boys wear chastity belts or spiked rings; and in extreme cases, castration." Paige details how circumcision became popular as a masturbation remedy:

In the 1890s, it became a popular technique to prevent, or cure, masturbatory insanity. In 1891 the president of the Royal College of Surgeons of England published On Circumcision as Preventive of Masturbation, and two years later another British doctor wrote Circumcision: Its Advantages and How to Perform It, which listed the reasons for removing the "vestigial" prepuce. Evidently the foreskin could cause "nocturnal incontinence," hysteria, epilepsy, and irritation that might "give rise to erotic stimulation and, consequently, masturbation." Another physician, P.C. Remondino, added that "circumcision is like a substantial and well-secured life annuity ... it insures better health, greater capacity for labor, longer life, less nervousness, sickness, loss of time, and less doctor bills." No wonder it became a popular remedy.[59]

At the same time circumcisions were advocated on men, clitoridectomies (removal of the clitoris) were also performed for the same reason (to treat female masturbators). The US "Orificial Surgery Society" for female "circumcision" operated until 1925, and clitoridectomies and infibulations would continue to be advocated by some through the 1930s. As late as 1936, L. E. Holt, an author of pediatric textbooks, advocated both circumcision and female genital mutilation as a treatment for masturbation.[59]

One of the leading advocates of circumcision was John Harvey Kellogg. He advocated the consumption of Kellogg's corn flakes to prevent masturbation, and he believed that circumcision would be an effective way to eliminate masturbation in males.

Covering the organs with a cage has been practiced with entire success. A remedy which is almost always successful in small boys is circumcision, especially when there is any degree of phimosis. The operation should be performed by a surgeon without administering an anesthetic, as the brief pain attending the operation will have a salutary effect upon the mind, especially if it be connected with the idea of punishment, as it may well be in some cases. The soreness which continues for several weeks interrupts the practice, and if it had not previously become too firmly fixed, it may be forgotten and not resumed. If any attempt is made to watch the child, he should be so carefully surrounded by vigilance that he cannot possibly transgress without detection. If he is only partially watched, he soon learns to elude observation, and thus the effect is only to make him cunning in his vice.

Robert Darby (2003), writing in the Medical Journal of Australia, noted that some 19th-century circumcision advocates—and their opponents—believed that the foreskin was sexually sensitive:

In the 19th century the role of the foreskin in erotic sensation was well understood by physicians who wanted to cut it off precisely because they considered it the major factor leading boys to masturbation. The Victorian physician and venereologist William Acton (1814–1875) damned it as "a source of serious mischief", and most of his contemporaries concurred. Both opponents and supporters of circumcision agreed that the significant role the foreskin played in sexual response was the main reason why it should be either left in place or removed. William Hammond, a Professor of Mind in New York in the late 19th century, commented that "circumcision, when performed in early life, generally lessens the voluptuous sensations of sexual intercourse", and both he and Acton considered the foreskin necessary for optimal sexual function, especially in old age. Jonathan Hutchinson, English surgeon and pathologist (1828–1913), and many others, thought this was the main reason why it should be excised.[9]

Born in the United Kingdom during the late-nineteenth century, John Maynard Keynes and his brother Geoffrey, were both circumcised in boyhood due to parents' concern about their masturbatory habits.[61] Mainstream pediatric manuals continued to recommend circumcision as a deterrent against masturbation until the 1950s.[9]

Spread and decline

Infant circumcision was taken up in the United Kingdom, the United States, Australia, New Zealand, and the English-speaking parts of Canada. Although it is difficult to determine historical circumcision rates, one estimate[62] of infant circumcision rates in the United States holds that 30% of newborn American boys were being circumcised in 1900, 55% in 1925, and 72% in 1950.

In South Korea, circumcision was largely unknown before the establishment of the United States trusteeship in 1945 and the spread of American influence.[63] More than 90% of South Korean high school boys are now circumcised at an average age of 12 years, which makes South Korea a unique case.[64] However circumcision rates are now declining in South Korea.[65]

Decline in circumcision in the English-speaking world began in the postwar period. The British paediatrician Douglas Gairdner published a famous study in 1949, The fate of the foreskin,[66][67] described as "a model of perceptive and pungent writing."[68] It revealed that for the years 1942–1947, about 16 children per year in England and Wales had died because of circumcision, a rate of about 1 per 6000 circumcisions.[66] The article had an influential impact on medical practice and public opinion.[69]

In 1949, a lack of consensus in the medical community as to whether circumcision carried with it any notable health benefit motivated the United Kingdom's newly formed National Health Service to remove infant circumcision from its list of covered services. Since then, circumcision has been an out-of-pocket cost to parents, and the proportion of circumcised men is around 9%.[70]

Similar trends have operated in Canada, (where public medical insurance is universal, and where private insurance does not replicate services already paid from the public purse) individual provincial health insurance plans began delisting non-therapeutic circumcision in the 1980s. Manitoba was the final province to delist non-therapeutic circumcision, which occurred in 2005.[71] The practice has also declined to about nine percent of newborn boys in Australia and is almost unknown in New Zealand.[72]

See also

- Bioethics of neonatal circumcision

- Children's rights

- Circumcision controversies

- Ethics of circumcision

- Prevalence of circumcision

References

- Marck, J (1997). "Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history". Health Transit Review. 7 (supplement): 337–360. PMID 10173099.

- Morrison J (1967). "The origins of the practices of circumcision and subincision among the Australian aborigines". The Medical Journal of Australia. 1 (3): 125–7. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.1967.tb21064.x. PMID 6018441.

- http://pacifichealthdialog.org.fj/Volume209/No20120_20Emergency20Health20In20The20Pacific/Original20Papers/Attitudes20of20Pacific20Island20parents20to20circumcision20of20boys.pdf

- "Estimated number of male newborn infants, and percent circumcised§ during birth hospitalization, by geographic region: United States, 1979-2008" (PDF). United States Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC).

- "SHEM". The Jewish Encyclopedia. Retrieved 17 December 2013.

- Amin Ud, Din M (2012). "Aposthia-A Motive of Circumcision Origin". Iranian Journal of Public Health. 41 (9): 84. PMC 3494220. PMID 23193511.

- Alphabet of Ben Sirah, Question #5 (23a–b)

- Ronald Immerman and Wade Mackey (1997). "A Biocultural Analysis of Circumcision". Social Biology. 44 (3): 265–275. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.1976.tb00285.x. PMID 9446966.

- Robert Darby (2003). "Medical history and medical practice: persistent myths about the foreskin". Medical Journal of Australia. 178 (4): 178–9. doi:10.5694/j.1326-5377.2003.tb05137.x. PMID 12580747.

- "Policy Statement On Circumcision" (PDF). Royal Australasian College of Physicians. September 2004.

- Robert Darby (2005). "The riddle of the sands: circumcision, history, and myth" (PDF). New Zealand Medical Journal. 118 (1218): 76–80. PMID 16027753.

- Immerman, R. S.; W. C. Mackey (Fall–Winter 1997). "A biocultural analysis of circumcision". Social Biology. 44 (3–4): 265–275. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9744.1976.tb00285.x. PMID 9446966.

- Wilson, Christopher G. (2008). "Male genital mutilation: an adaptation to sexual conflict" (PDF). Evolution and Human Behavior. 29 (3): 149–164. doi:10.1016/j.evolhumbehav.2007.11.008. Archived from the original (PDF) on 8 January 2016. Retrieved 31 January 2011.

- Mark, Elizabeth Wyner (2003). The Covenant of Circumcision: New Perspectives on an Ancient Jewish Rite (illustrated ed.). University Press of New England. p. 44. ISBN 1584653078. Archived from the original on 2019.

- Wagner, G. (1949). The Bantu of North Kavirondo. London: International African Institute.

- Marck, Jeff (1997). "Aspects of male circumcision in sub-equatorial African culture history" (PDF). Health Transition Review (7 Supplement): 337–359. Archived from the original (PDF) on 6 September 2008. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- "South Africa circumcision deaths". BBC News. 15 July 2003. Retrieved 7 April 2009.

- Gollaher 2000, p. 2

- Herodotus (29 November 2005). The History of Herodotus. ISBN 1-4165-1697-2.

- Gollaher (2000)

- "Circumcision". Encyclopædia Britannica (10th ed.). 1902.

- Gollaher 2000, p. 3

- "7. Cutting Covenants | Religious Studies Center". rsc.byu.edu. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- "Cutting a Covenant". Bible Study Magazine. Retrieved 11 August 2019.

- Mark Popovsky (2010). "Circumcision". In David A. Leeming; Kathryn Madden; Stanton Marlan (eds.). Encyclopedia of Psychology and Religion. New York: Springer. pp. 153–154.

- Hodges, F. M. (Fall 2001). "The ideal prepuce in ancient Greece and Rome: male genital aesthetics and their relation to lipodermos, circumcision, foreskin restoration, and the kynodesme". The Bulletin of the History of Medicine. 75 (3): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485.

- Suetonius (translated and annotated by J. C. Rolfe) (c. 110). "De Vita Caesarum-Domitianus". Ancient History Sourcebook at fordham.edu. Retrieved 9 April 2008. The Romans applied the term curtus (lit., "cut short") to circumcised men at least in poetic contexts, e.g. at Horace, Sermones i.9.70.

- Rubin, J. P. (July 1980). "Celsus' decircumcision operation: medical and historical implications". Urology. 16 (1): 121–4. doi:10.1016/0090-4295(80)90354-4. PMID 6994325.

- Hall, R. G. (August 1992). "Epispasm: circumcision in reverse". Bible Review: 52–7.

- Peron, James E. (Spring 2000). "Circumcision: Then and Now". Many Blessings (volume III). pp. 41–42.

- Hillar, Marian. "Philo of Alexandria (20 B.C.E.-50 C.E.)". The Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- Philo Judaeus. "A Treatise on Circumcision". thriceholy.net. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- Gollaher 2000, p. 13

- Gollaher 2000, p. 21

- The Guide of the Perplexed. Translated and with an Introduction and Notes by Shlomo Pines. Chicago: Univ. of Chicago Press, 1963, Part III, ch. 49, p. 609.Moses Maimonides (translated by Shlomo Pines) (1963). "Guide to the Perplexed by". University of Chicago. Retrieved 25 September 2008.

- Maimonides, Moses (translated by Michael Friedländer) (1885). The Guide of the Perplexed. London: Trübner and co. pp. 267–9. ISBN 0-524-08303-7.

- Lisa Braver Moss. "Circumcision: A Jewish Inquiry". Beliefnet. Retrieved 9 April 2008.

- Davis, Dena S. (Summer 2001). "Male and female genital alteration: a collision course with the law". Journal of Law-medicine. 11: 487–570.

- Gollaher 2000, p. 22

- Josephus. "How Helene the Queen of Adiabene and her son Izates, embraced the Jewish religion; and how Helene supplied the poor with corn, when there was a great famine at Jerusalem". Antiquities of the Jews – Book XX, Chapter 2, verse 4. Christian Classics Ethereal Library. Retrieved 29 September 2008.

- Michael Glass (October 2001). "The New Testament and Circumcision". Circumcision Information and Resource Pages.

- "Archived copy". Archived from the original on 13 August 2007. Retrieved 2016-02-08.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- Julian of Toledo (1862). Historia rebellionis Paulli adversus Wambam Gothorum Regem (in Latin). apud Garnier fratres et J.-P. Migne successores. p. 10. reprinted in Jacques Paul Migne, ed. (1862). Patrologiæ cursus completus, seu bibliotheca universalis, integra, uniformis, commoda, oeconomica, Omnium SS. Patrium, Doctorum scriptoriumque, eccliasticorum. pp. 771–774.

- "Eccumenical Council of Florence and Council of Basel". EWTN Global Catholic Television Network Library. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- "Male Circumcision: context, criteria and culture". UNAIDS. 26 February 2007. Retrieved 8 April 2016.

- El-Hout Y, Khauli RB (September 2007). "The case for routine circumcision". Journal of Men's Health. 4 (3): 300–305. doi:10.1016/j.jmhg.2007.05.007. Archived from the original on 2 January 2013.

- Robert Darby. "A short history of the world's most controversial surgery". Circumcision Information Australia. Archived from the original on 19 July 2008. Retrieved 7 October 2008., a review of Gollaher, David L. (2000). Circumcision: A history of the world's most controversial surgery. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04397-6.

- Cozijin, John; Darby, Roger (16 October 2013). "The British Royal Family's Circumcision Tradition Genesis and Evolution of a Contemporary Legend". SAGE Open. 3. doi:10.1177/2158244013508960.

- "The crotchets of Sir Jonathan Hutchinson". History of Circumcision. Archived from the original on 2 June 2018. Retrieved 21 July 2014.

- Epstein E (1874). "Have the Jews any Immunity from Certain Diseases?". Medical and Surgical Reporter. Philadelphia. XXX: 40–41.

- Hutchinson J (1855). "On the influence of circumcision in preventing syphilis". Medical Times and Gazette. NS. II: 542–3.

- Weiss, HA; Thomas, SL; Munabi SK; Hayes RJ (April 2006). "Male circumcision and risk of syphilis, chancroid, and genital herpes: a systematic review and meta-analysis". Sexually Transmitted Infections. 82 (2): 101–9. doi:10.1136/sti.2005.017442. PMC 2653870. PMID 16581731.

- "A plea for circumcison", Archives of Surgery, Vol. II, 1890, p. 15; reprinted in British Medical Journal, 27 September 1890, p. 769.

- "On circumcision as a preventive of masturbation", Archives of surgery, Vol. II, 1890, p. 267-9

- Kent, Susan Kingsley (1999). Gender and power in Britain, 1640–1990. Routledge. p. 189. ISBN 0-415-14742-5.

- Fennell, Phil (1999). Treatment without consent: law, psychiatry and the treatment of mentally disordered people since 1845. Routledge. pp. 66–69. ISBN 0-415-07787-7.

- Vergnani, Linda (9 May 2003). "'Uterine fury' - now sold in chemists". Times Higher Education. Retrieved 7 October 2009.

-

- Gollaher DL (1994). "From ritual to science: the medical transformation of circumcision in America". Journal of Social History. 28 (1): 5–36. doi:10.1353/jsh/28.1.5.

- Paige KE (May 1978). "The Ritual of Circumcision". Human Nature: 40–8.

- Waldeck, S. E. (2003). "Using Male Circumcision to Understand Social Norms as Multipliers". University of Cincinnati Law Review. 72 (2): 455–526.

- R. Darby, A Surgical Temptation (2010) p. 298

- Hugh O'Donnell (April 2001). "The United States' Circumcision Century". Circumcision Statistics of the 20th Century.

- "Extraordinarily high rates of male circumcision in South Korea: history and underlying causes", BJU International, Volume 89: Pages 48-54, January 2002, archived at the Circumcision Reference Library

- Pang, MG; Kim DS (2002). "Extraordinarily high rates of male circumcision in South Korea: history and underlying causes". BJU Int. 89 (1): 48–54. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410X.2002.02545.x. PMID 11849160.

- DaiSik Kim; Sung-Ae Koo; Myung-Geol Pang (2012). "Decline in male circumcision in South Korea" (PDF). BMC Public Health. 12: 1067–73. doi:10.1186/1471-2458-12-1067. PMC 3526493. PMID 23227923.

- Gairdner, Douglas (December 1949). "The Fate of the Foreskin". British Medical Journal. 2 (4642): 1433–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.4642.1433. PMC 2051968. PMID 15408299.

- Gairdner, Douglas (February 1950). "The Fate of the Foreskin (letter of response)". British Medical Journal. 1 (4650): 439–440. doi:10.1136/bmj.1.383.439. PMC 2036928.

- The James Spence Medal. Archives of Disease in Childhood. 1977;52:85–86. doi:10.1136/adc.52.2.85.

- Wallerstein E. Circumcision: the uniquely American medical enigma. Urol Clinic North Am. 1985;12(1):123–32. PMID 3883617.

- "Circumcision, the ultimate parenting dilemma". BBC News. 12 August 2012. Retrieved 13 March 2016.

- Treasury Board of Canada secretariat. "Public Service Health Care Plan Bulletin Number 17". Archived from the original on 3 November 2007. Retrieved 4 September 2007.

- Incidence and prevalence of circumcision in Australia, Circumcision Information Australia, January 1913, retrieved 24 January 2015

Bibliography

- Gollaher, David L. (2000). Circumcision: A history of the world's most controversial surgery. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 0-465-04397-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Paul M. Fleiss, M.D. and Frederick Hodges, D. Phil. What Your Doctor May Not Tell You About Circumcision. New York: Warner Books, 2002: pp. 118–146, paperback (ISBN 0-446-67880-5)

- Leonard B. Glick. Marked in Your Flesh: Circumcision from Ancient Judea to Modern America. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. (ISBN 0-19-517674-X)

- Robert J. L. Darby. A Surgical Temptation: The Demonization of the Foreskin and the Rise of Circumcision in Britain. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2005. (ISBN 0-226-13645-0)

External links

- Jewish Encyclopedia: Circumcision

- VIDEO – Male Circumcision: History, Ethics and Surgical Considerations Dr. Benjamin Mandel speaks at the University of Wisconsin School of Medicine and Public Health, December 2007.

- Peter Charles Remondino. History of Circumcision from the Earliest Times to the Present. Philadelphia and London; F. A. Davis; 1891.

- Doyle, D (2005). "Ritual Male Circumcision: A Brief History" (PDF). Journal of the Royal College of Physicians. 35: 279–285.

- Hodges FM. (Fall 2001). "The Ideal Prepuce in Ancient Greece and Rome: Male Genital Aesthetics and Their Relation to Lipodermos, Circumcision, Foreskin Restoration, and the Kynodesme". Bull. Hist. Med. 75 (3): 375–405. doi:10.1353/bhm.2001.0119. PMID 11568485.

- John M. Ephron (2001). "In Praise of German Ritual: Modern Medicine and the Defense of Ancient Traditions". Medicine and the German Jews. New Haven: Yale University Press. pp. 222–233. ISBN 0-300-08377-7.

- Dunsmuir WD, Gordon EM (1999). "The history of circumcision". BJU Int. 83 (Suppl 1): 1–12. doi:10.1046/j.1464-410x.1999.0830s1001.x. PMID 10349408.

- Gollaher DL (1994). "From ritual to science: the medical transformation of circumcision in America". Journal of Social History. 28 (1): 5–36. doi:10.1353/jsh/28.1.5.

- The History of Circumcision website