Bar Kokhba revolt

The Bar Kokhba revolt (Hebrew: מֶרֶד בַּר כּוֹכְבָא; Mered Bar Kokhba) was a rebellion of the Jews of the Roman province of Judea, led by Simon bar Kokhba, against the Roman Empire. Fought circa 132–136 CE,[4] it was the last of three major Jewish–Roman wars, so it is also known as The Third Jewish–Roman War or The Third Jewish Revolt. Some historians also refer to it as the Second Revolt[5] of Judea, not counting the Kitos War (115–117 CE), which had only marginally been fought in Judea.

| Bar Kokhba revolt | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Jewish–Roman wars | |||||||||

Simon bar Kokhba (detail from the Knesset Menorah, Jerusalem) | |||||||||

| |||||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||||

|

|

| ||||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||||

|

Hadrian Q. Tineius Rufus (DOW) Sextus Julius Severus Publicius Marcellus Titus Haterius Nepos Quintus Lollius Urbicus |

Simon bar Kokhba † Eleazar of Modi'im † Rabbi Akiva Yeshua ben Galgula † Yonatan ben Baiin Masbelah ben Shimon Elazar ben Khita Yehuda bar Menashe Shimon ben Matanya | ||||||||

| Units involved | |||||||||

|

Legio III Cyrenaica Legio X Fretensis Legio VI Ferrata Legio III Gallica Legio XXII Deiotariana Legio II Traiana Legio X Gemina Legio IX Hispana? Legio V Macedonica (partial) Legio XI Claudia (partial) Legio XII Fulminata (partial) Legio IV Flavia Felix (partial) |

Bar Kokhba's army • Bar Kokhba's guard • Local militias Samaritan Youth Bands | ||||||||

| Strength | |||||||||

|

2 legions - 20,000 (132-133) 5 legions - 80,000 (133-134) 6-7 full legions, cohorts of 5-6 more, 30-50 auxilary units - 120,000 (134-135) |

200,000–400,000b Jewish militiamen • 12,000 Bar Kokhba's guard force | ||||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||||

|

Legio XXII Deiotariana destroyedc Legio IX Hispana possibly destroyed[1] Legio X Fretensis sustained heavy casualties[2] | 200,000–400,000 Jewish militiamen killed or enslaved | ||||||||

|

Total: 580,000 Jews killed, 50 fortified towns and 985 villages razed; "many more" Jews dead as a result of famine and disease.a Massive Roman military casualtiesa | |||||||||

|

[a] - per Cassius Dio[3] | |||||||||

The revolt erupted as a result of religious and political tensions in Judea following on the failed First Revolt in 66–73 CE. These tensions were related to the establishment of a large Roman military presence in Judea, changes in administrative life and the economy, together with the outbreak and suppression of Jewish revolts from Mesopotamia to Libya and Cyrenaica.[6] The proximate reasons seem to be the construction of a new city, Aelia Capitolina, over the ruins of Jerusalem and the erection of a temple to Jupiter on the Temple Mount.[7] The Church Fathers and rabbinic literature emphasize the role of Rufus, governor of Judea, in provoking the revolt.[8]

In 132, the revolt led by Bar Kokhba quickly spread from central Judea across the country, cutting off the Roman garrison in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem).[9] Quintus Tineius Rufus, the provincial governor at the time of the erupting uprising, was attributed with the failure to subdue its early phase. Rufus is last recorded in 132, the first year of the rebellion; whether he died or was replaced is uncertain. Despite arrival of significant Roman reinforcements from Syria, Egypt and Arabia, initial rebel victories over the Romans established an independent state over most parts of Judea Province for over two years, as Simon bar Kokhba took the title of Nasi ("prince"). As well as leading the revolt, he was regarded by many Jews as the Messiah, who would restore their national independence.[10] This setback, however, caused Emperor Hadrian to assemble a large-scale Roman force from across the Empire, which invaded Judea in 134 under the command of General Sextus Julius Severus. The Roman army was made up of six full legions with auxiliaries and elements from up to six additional legions, which finally managed to crush the revolt.[11]

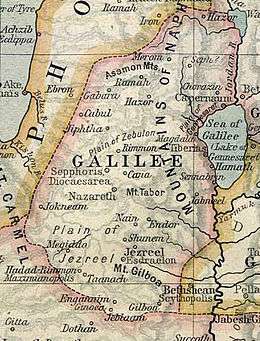

The Bar Kokhba revolt resulted in the extensive depopulation of Judean communities, more so than during the First Jewish–Roman War of 70 CE.[12] According to Cassius Dio, 580,000 Jews perished in the war and many more died of hunger and disease. In addition, many Judean war captives were sold into slavery.[13] The Jewish communities of Judea were devastated to an extent which some scholars describe as a genocide.[12][14] However, the Jewish population remained strong in other parts of Palestine, thriving in Galilee, Golan, Bet Shean Valley and the eastern, southern and western edges of Judea.[15] Roman casualties were also considered heavy – XXII Deiotariana was disbanded after serious losses.[16][17] In addition, some historians argue that Legio IX Hispana's disbandment in the mid-2nd century could have been a result of this war.[1] In an attempt to erase any memory of Judea or Ancient Israel, Emperor Hadrian wiped the name off the map and replaced it with Syria Palaestina.[18][19][20] However, there is only circumstantial evidence linking Hadrian with the name change and the precise date is not certain.[21] The common view that the name change was intended to "sever the connection of the Jews to their historical homeland" is disputed.[22]

The Bar Kokhba revolt greatly influenced the course of Jewish history and the philosophy of the Jewish religion. Despite easing the persecution of Jews following Hadrian's death in 138 CE, the Romans barred Jews from Jerusalem, except for attendance in Tisha B'Av. Jewish messianism was abstracted and spiritualized, and rabbinical political thought became deeply cautious and conservative. The Talmud, for instance, refers to Bar Kokhba as "Ben-Kusiba", a derogatory term used to indicate that he was a false Messiah. It was also among the key events to differentiate Christianity as a religion distinct from Judaism.[23] Although Jewish Christians regarded Jesus as the Messiah and did not support Bar Kokhba,[24] they were barred from Jerusalem along with the other Jews.[25]

Background

After the First Jewish–Roman War (66-73 CE), the Roman authorities took measures to suppress the rebellious province of Roman Judea. Instead of a procurator, they installed a praetor as a governor and stationed an entire legion, the X Fretensis, in the area. Tensions continued to build up in the wake of the Kitos War, the second large-scale Jewish insurrection in the Eastern Mediterranean during 115-117, the final stages of which saw fighting in Judea. Mismanagement of the province during the early 2nd century might well have led to the proximate causes of the revolt, largely bringing governors with clear anti-Jewish sentiments to run the province. Gargilius Antiques may have preceded Rufus during the 120s.[26] The Church Fathers and rabbinic literature emphasize the role of Rufus in provoking the revolt.[8]

Historians have suggested multiple reasons for the sparking of the Bar Kokhba revolt, long-term and proximate. Several elements are believed to have contributed to the rebellion; changes in administrative law, the diffuse presence of Romans, alterations in agricultural practice with a shift from landowning to sharecropping, the impact of a possible period of economic decline, and an upsurge of nationalism, the latter influenced by similar revolts among the Jewish communities in Egypt, Cyrenaica and Mesopotamia during the reign of Trajan in the Kitos War.[7] The proximate reasons seem to centre around the construction of a new city, Aelia Capitolina, over the ruins of Jerusalem and the erection of a temple to Jupiter on the Temple mount.[7] One interpretation involves the visit in 130 CE of Hadrian to the ruins of the Jewish Temple in Jerusalem. At first sympathetic towards the Jews, Hadrian promised to rebuild the Temple, but the Jews felt betrayed when they found out that he intended to build a temple dedicated to Jupiter upon the ruins of the Second Temple.[3] A rabbinic version of this story claims that Hadrian planned on rebuilding the Temple, but that a malevolent Samaritan convinced him not to. The reference to a malevolent Samaritan is, however, a familiar device of Jewish literature.[27]

An additional legion, the VI Ferrata, arrived in the province to maintain order. Works on Aelia Capitolina, as Jerusalem was to be called, commenced in 131 CE. The governor of Judea, Tineius Rufus, performed the foundation ceremony, which involved ploughing over the designated city limits.[28] "Ploughing up the Temple",[29][30][31] seen as a religious offence, turned many Jews against the Roman authorities. The Romans issued a coin inscribed Aelia Capitolina.[32][33][34]

A disputed tradition, based on the single source of the Historia Augusta, regarded as 'unreliable and problematic,'[35][36] states tensions rose after Hadrian banned circumcision, referred to as mutilare genitalia [37][38] taken to mean brit milah.[39] Were the claim true it has been conjectured that Hadrian, as a Hellenist, would have viewed circumcision as an undesirable form of mutilation.[40] The claim is often considered suspect.[41][42]

Timeline of events

First phase

Eruption of the revolt

Jewish leaders carefully planned the second revolt to avoid the numerous mistakes that had plagued the first First Jewish–Roman War sixty years earlier.[43] In 132, the revolt, led by Simon bar Kokhba and Elasar, quickly spread from Modi'in across the country, cutting off the Roman garrison in Jerusalem.[9] Although Rufus was in charge during the early phase of the uprising, he disappears from the record after 132 for unknown reasons. Shortly after the eruption of the revolt, Bar Kokhba's rebels inflicted heavy casualties to Legio X Fretensis, based in Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem). At that point, Legio VI Ferrata was sent to reinforce the Roman position from Legio base in Yizrael Valley, fielding altogether some 20,000 Roman troops, but was unable to subdue the rebels, who nearly conquered Jerusalem.

Stalemate and reinforcements

Given the continuing inability of Legio X and Legio VI to subdue the rebels, additional reinforcements were dispatched from neighbouring provinces. Gaius Publicus Marcellus, the Legate of Roman Syria, arrived commanding Legio III Gallica, while Titus Haterius Nepos, the governor of Roman Arabia, brought Legio III Cyrenaica. Later on it is proposed by some historians that Legio XXII Deiotariana was sent from Arabia Petraea, but was ambushed and massacred on its way to Aelia Capitolina (Jerusalem), and possibly disbanded as a result. Legio II Traiana Fortis, previously stationed in Egypt, may have also arrived in Judea in this stage. By that time the number of Roman troops in Judea stood at nearly 80,000 - a number still inferior to rebel forces, who were also better familiar with the terrain and occupied strong fortifications.

Many Jews from the diaspora made their way to Judea to join Bar Kokhba's forces from the beginning of the rebellion, with the Talmud recorded tradition that hard tests were imposed on recruits due to the inflated number of volunteers. From some documents evidence was also found for non-Jews enlisting in Bar Kokhba's forces, though it is not conclusive. According to Jewish sources some 400,000 men were at the disposal of Bar Kokhba at the peak of the rebellion, though historians tend to more conservative numbers of 200,000.

Second phase

From guerilla warfare to open engagement

The outbreak and initial success of the rebellion took the Romans by surprise. The rebels incorporated combined tactics to fight the Roman Army. According to some historians, Bar Kokhba's army mostly practiced guerrilla warfare, inflicting heavy casualties. This view is largely supported by Cassius Dio, who wrote that the revolt began with covert attacks in line with preparation of hideout systems, though after taking over the fortresses Bar Kokhba turned to direct engagement due to his superiority in numbers. Only after several painful defeats in the field did the Romans decide to avoid open conflict and instead methodically besiege individual Judean cities.

Rebel Judean statehood

Simon Bar Kokhba took the title Nasi Israel and ruled over an entity that was virtually independent for two and a half years. The Jewish sage Rabbi Akiva identified Simon Bar Kosiba as the Jewish messiah, and gave him the surname "Bar Kokhba" meaning "Son of a Star" in the Aramaic language, from the Star Prophecy verse from Numbers 24:17: "There shall come a star out of Jacob".[44] The name Bar Kokhba does not appear in the Talmud but in ecclesiastical sources.[45] The era of the redemption of Israel was announced, contracts were signed and a large quantity of Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was struck over foreign coins.

From open warfare to rebel defensive tactics

With the slowly advancing Roman army cutting supply lines, the rebels engaged in long-term defense. The defense system of Judean towns and villages was based mainly on hideout caves, which were created in large numbers in almost every population center. Many houses utilized underground hideouts, where Judean rebels hoped to withstand Roman superiority by the narrowness of the passages and even ambushes from underground. The cave systems were often interconnected and used not only as hideouts for the rebels but also for storage and refuge for their families.[46] Hideout systems were employed in the Judean hills, the Judean desert, northern Negev, and to some degree also in Galilee, Samaria and Jordan Valley. As of July 2015 some 350 hideout systems have been mapped within the ruins of 140 Jewish villages.[47]

Third phase

Julius Severus' campaign

Following a series of setbacks, Hadrian called his general Sextus Julius Severus from Britain, and troops were brought from as far as the Danube. In 133/4, Severus landed in Judea with a massive army, bringing three legions from Europe (including Legio X Gemina and possibly also Legio IX Hispana), cohorts of additional legions and between 30 and 50 auxiliary units. He took the title of provincial governor and initiated a massive campaign to systematically subdue Judean rebel forces. Severus' arrival almost doubled the number of Roman troops facing the rebels.

The size of the Roman army amassed against the rebels was much larger than that commanded by Titus sixty years earlier - nearly one third of the Roman army took part in the campaign against Bar Kokhba. It is estimated that forces from at least 10 legions participated in Severus' campaign in Judea, including Legio X Fretensis, Legio VI Ferrata, Legio III Gallica, Legio III Cyrenaica, Legio II Traiana Fortis, Legio X Gemina, cohorts of Legio V Macedonica, cohorts of Legio XI Claudia, cohorts of Legio XII Fulminata and cohorts of Legio IV Flavia Felix, along with 30-50 auxiliary units, for a total force of 60,000–120,000 Roman soldiers facing Bar Kokhba's rebels. In addition, it is generally considered that Legio XXII Deiotoriana took part in the campaign and was annihilated. It is plausible that Legio IX Hispana was among the legions Severus brought with him from Europe, and that its demise occurred during Severus' campaign, as its disappearance during the second century is often attributed to this war.[1]

Battle of Tel Shalem

According to some views, one of the crucial battles of the war took place near Tel Shalem in the Beit She'an valley, near what is now identified as the legionary camp of Legio VI Ferrata. Next to the camp, archaeologists have unearthed the remnants of a triumphal arch, which featured a dedication to Emperor Hadrian, which most likely refers to the defeat of Bar Kokhba's army.[48] Additional finds at Tel Shalem, including a bust of Emperor Hadrian, specifically link the site to the period. The theory for a major battle in Tel Shalem implies a significant extension of the area of the rebellion - while some historians confine the conflict to Judea proper, the location of Tel Shalem suggests that the war encompassed the northern Jordan Valley as well, some 50 km north of the war's minimal boundaries.

Judean highlands and desert

Simon bar Kokhba declared Herodium as his secondary headquarters. Archaeological evidence for the revolt was found all over the site, from the outside buildings to the water system under the mountain. Inside the water system, supporting walls built by the rebels were discovered, and another system of caves was found. Inside one of the caves, burned wood was found which was dated to the time of the revolt. The fortress was besieged by the Romans in late 134 and was taken by the end of the year or early in 135. Its commander was Yeshua ben Galgula, likely Bar Kokhba's second in command.

Fourth phase

The last phase of the revolt is characterized by Bar Kokhba's loss of territorial control, with the exception of the surroundings of the Betar fortress, where he made his last stand against the Romans. The Roman Army had meanwhile turned to eradicate smaller fortresses and hideout systems of captured villages, turning the conquest into a campaign of annihilation.

Siege of Betar

After losing many of their strongholds, Bar Kokhba and the remnants of his army withdrew to the fortress of Betar, which subsequently came under siege in the summer of 135. Legio V Macedonica and Legio XI Claudia are said to have taken part in the siege.[49] According to Jewish tradition, the fortress was breached and destroyed on the fast of Tisha B'av, the ninth day of the lunar month Av, a day of mourning for the destruction of the First and the Second Jewish Temple. Rabbinical literature ascribes the defeat to Bar Kokhba killing his maternal uncle, Rabbi Elazar Hamudaʻi, after suspecting him of collaborating with the enemy, thereby forfeiting Divine protection.[50] The horrendous scene after the city's capture could be best described as a massacre.[51] The Jerusalem Talmud relates that the number of dead in Betar was enormous, that the Romans "went on killing until their horses were submerged in blood to their nostrils."[52]

Final accords

According to a Rabbinic midrash, the Romans executed eight leading members of the Sanhedrin (The list of Ten Martyrs include two earlier Rabbis): R. Akiva; R. Hanania ben Teradion; the interpreter of the Sanhedrin, R. Huspith; R. Eliezer ben Shamua; R. Hanina ben Hakinai; R. Jeshbab the Scribe; R. Yehuda ben Dama; and R. Yehuda ben Baba. The Rabbinic account describes agonizing tortures: R. Akiva was flayed with iron combs, R. Ishmael had the skin of his head pulled off slowly, and R. Hanania was burned at a stake, with wet wool held by a Torah scroll wrapped around his body to prolong his death.[53] Bar Kokhba's fate is not certain, with two alternative traditions in the Babylonian Talmud ascribing the death of Bar Kokhba either to a snake bite or other natural causes during the Roman siege or possibly killed on the orders of the Sanhedrin, as a false Messiah. According to Lamentations Rabbah, the head of Bar Kokhba was presented to Emperor Hadrian after the Siege of Betar.

Following the Fall of Betar, the Roman forces went on a rampage of systematic killing, eliminating all remaining Jewish villages in the region and seeking out the refugees. Legio III Cyrenaica was the main force to execute this last phase of the campaign. Historians disagree on the duration of the Roman campaign following the fall of Betar. While some claim further resistance was broken quickly, others argue that pockets of Jewish rebels continued to hide with their families into the winter months of late 135 and possibly even spring 136. By early 136 however, it is clear that the revolt was defeated.[54]

Casualties

According to Cassius Dio, 580,000 Jews were killed in the overall operations, and 50 fortified towns and 985 villages were razed to the ground,[3][55] with many more Jews dying of famine and disease. The Jewish communities of Judea were devastated to an extent which some scholars describe as a genocide.[12][14] Schäfer suggests that Dio exaggerated his numbers.[56] On the other hand, Cotton considered Dio's figures highly plausible, in light of accurate Roman census declarations.[57] In addition, many Judean war captives were sold into slavery.[13]

The revolt was led by the Judean Pharisees, with other Jewish and non-Jewish factions also playing a role. Jewish communities of Galilee who sent militants to the revolt in Judea were largely spared total destruction, though they did suffer persecutions and massive executions. Samaria partially supported the revolt, with evidence accumulating that notable numbers of Samaritan youths participated in Bar Kokhba's campaigns; though Roman wrath was directed at Samaritans, their cities were also largely spared from the total destruction unleashed on Judea. Eusebius of Caesarea wrote that Jewish Christians were killed and suffered "all kinds of persecutions" at the hands of rebel Jews when they refused to help Bar Kokhba against the Roman troops.[58][59] The Greco-Roman population of the region also suffered severely during the early stage of the revolt, persecuted by Bar Kokhba's forces.

Cassius Dio also wrote: "Many Romans, moreover, perished in this war. Therefore, Hadrian, in writing to the Senate, did not employ the opening phrase commonly affected by the emperors: 'If you and your children are in health, it is well; I and the army are in health.'"[60] Some argue that the exceptional number of preserved Roman veteran diplomas from the late 150s and 160 CE indicate an unprecedented conscription across the Roman Empire to replenish heavy losses within military legions and auxiliary units between 133 and 135, corresponding to the revolt.[61]

As noted above, XXII Deiotariana was disbanded after serious losses.[16][17] In addition, some historians argue that Legio IX Hispana's disbandment in the mid-2nd century could have been a result of this war.[1] Previously it had generally been accepted that the Ninth disappeared around 108 CE, possibly suffering its demise in Britain, according to Mommsen; but archaeological findings in 2015 from Nijmegen, dated to 121 CE, contained the known inscriptions of two senior officers who were deputy commanders of the Ninth in 120 CE, and lived on for several decades to lead distinguished public careers. It was concluded that the Legion was disbanded between 120 and 197 CE - either as a result of fighting the Bar Kokhba revolt, or in Cappadocia (161), or at the Danube (162).[62] Legio X Fretensis sustained heavy casualties during the revolt.[2]

Aftermath

Immediate consequences

.jpg)

After the suppression of the revolt, Hadrian's proclamations sought to root out Jewish nationalism in Judea,[7] which he saw as the cause of the repeated rebellions. He prohibited Torah law and the Hebrew calendar, and executed Judaic scholars. The sacred scrolls of Judaism were ceremonially burned on the Temple Mount. At the former Temple sanctuary, he installed two statues, one of Jupiter, another of himself. In an attempt to erase any memory of Judea or Ancient Israel, he wiped the name off the map and replaced it with Syria Palaestina.[18][19][20] By destroying the association of Jews with Judea and forbidding the practice of the Jewish faith, Hadrian aimed to root out a nation that had inflicted heavy casualties on the Roman Empire. Similarly, he re-established Jerusalem as the Roman pagan polis of Aelia Capitolina, with Jews forbidden to enter, except on the day of Tisha B'Av.[63]

Modern historians view the Bar Kokhba Revolt as having decisive historic importance.[12] They note that, unlike the aftermath of the First Jewish–Roman War chronicled by Josephus, the Jewish population of Judea was devastated after the Bar Kokhba Revolt,[12] being killed, exiled, or sold into slavery, and Jewish religious and political authority was suppressed far more brutally than before. The Jews suffered a serious blow in Jerusalem and its environs in Judea, but the Jewish communities thrived in the remaining regions of Palestine—e.g., Galilee, Bet Shean, Caesarea, Golan and along the edges of Judea[15] The massive destruction and death in the course of the revolt has led scholars such as Bernard Lewis to date the beginning of the Jewish diaspora from this date. Hadrian's death in 138 CE marked a significant relief to the surviving Jewish communities. Some of the Judean survivors resettled in Galilee, with some rabbinical families gathering in Sepphoris.[64] Rabbinic Judaism had already become a portable religion, centered on synagogues.

Judea would not be a center of Jewish religious, cultural, or political life again until the modern era, although Jews continued to sporadically populate it and important religious developments still took place there. Galilee became an important center of Rabbinic Judaism, where the Jerusalem Talmud was compiled in the 4th-5th centuries CE. In the aftermath of the defeat, the maintenance of Jewish settlement in Palestine became a major concern of the rabbinate.[65] The Sages endeavoured to halt Jewish dispersal, and even banned emigration from Palestine, branding those who settled outside its borders as idolaters.[65]

Later relations between the Jews and the Roman Empire

Relations between the Jews in the region and the Roman Empire continued to be complicated. Constantine I allowed Jews to mourn their defeat and humiliation once a year on Tisha B'Av at the Western Wall. In 351–352 CE, the Jews of Galilee launched yet another revolt, provoking heavy retribution.[66] The Gallus revolt came during the rising influence of early Christians in the Eastern Roman Empire, under the Constantinian dynasty. In 355, however, the relations with the Roman rulers improved, upon the rise of Emperor Julian, the last of the Constantinian dynasty, who, unlike his predecessors, defied Christianity. In 363, not long before Julian left Antioch to launch his campaign against Sassanian Persia, he ordered the Jewish Temple rebuilt in his effort to foster religions other than Christianity.[67] The failure to rebuild the Temple has mostly been ascribed to the dramatic Galilee earthquake of 363, and traditionally also to the Jews' ambivalence about the project. Sabotage is a possibility, as is an accidental fire, though Christian historians of the time ascribed it to divine intervention.[68] Julian's support of Judaism caused Jews to call him "Julian the Hellene".[69] Julian's fatal wound in the Persian campaign put an end to Jewish aspirations, and Julian's successors embraced Christianity through the entirety of Byzantine rule of Jerusalem, preventing any Jewish claims.

In 438 CE, when the Empress Eudocia removed the ban on Jews' praying at the Temple site, the heads of the Community in Galilee issued a call "to the great and mighty people of the Jews" which began: "Know that the end of the exile of our people has come!" However the Christian population of the city saw this as a threat to their primacy, and a riot erupted which chased Jews from the city.[70][71]

During the 5th and the 6th centuries, a series of Samaritan revolts broke out across the Palaestina Prima province. Especially violent were the third and the fourth revolts, which resulted in near annihilation of the Samaritan community.[72] It is likely that the Samaritan revolt of 556 was joined by the Jewish community, which had also suffered brutal suppression of their religion under Emperor Justinian.[73][74][75]

In the belief of restoration to come, in the early 7th century the Jews made an alliance with the Persians, joining the Persian invasion of Palaestina Prima in 614 to overwhelm the Byzantine garrison, and gaining autonomous rule over Jerusalem.[76] However, their autonomy was brief: the Jewish leader was shortly assassinated during a Christian revolt and, though Jerusalem was reconquered by Persians and Jews within 3 weeks, it fell into anarchy. With the subsequent withdrawal of Persian forces, Jews surrendered to the Byzantines in 625 CE or 628 CE, but were massacred by Christians in 629 CE, with the survivors fleeing to Egypt. Byzantine control of the region was finally lost to Muslim Arab armies in 637 CE, when Umar ibn al-Khattab completed the conquest of Akko.

Legacy

In the post-rabbinical era, the Bar Kokhba Revolt became a symbol of valiant national resistance. The Zionist youth movement Betar took its name from Bar Kokhba's traditional last stronghold, and David Ben-Gurion, Israel's first prime minister, took his Hebrew last name from one of Bar Kokhba's generals.[77]

The disastrous end of the revolt also occasioned major changes in Jewish religious thought. Jewish messianism was abstracted and spiritualized, and rabbinical political thought became deeply cautious and conservative. The Talmud, for instance, refers to Bar Kokhba as "Ben-Kusiba," a derogatory term used to indicate that he was a false Messiah. The deeply ambivalent rabbinical position regarding Messianism, as expressed most famously in Maimonides "Epistle to Yemen," would seem to have its origins in the attempt to deal with the trauma of a failed Messianic uprising.[78]

A popular children's song, included in the curriculum of Israeli kindergartens, has the refrain "Bar Kokhba was a Hero/He fought for Liberty," and its words describe Bar Kokhba as being captured and thrown into a lion's den, but managing to escape riding on the lion's back.[79]

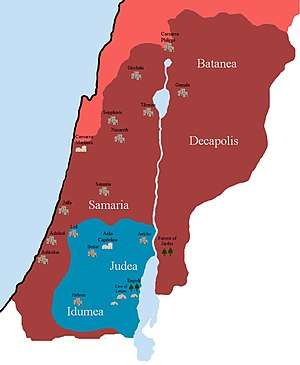

Geographic extent of the revolt

It is generally accepted that the Bar Kokhba revolt encompassed all of Judea, namely the villages of the Judean hills, the Judean desert, and northern parts of the Negev desert. The minimalistic approach limits the borders of the war to these areas, but there are also significant findings which may support a wider view of the extent of the revolt. Among those findings are the rebel hideout systems in the Galilee, which greatly resemble the Bar Kokhba hideouts in Judea, and though are less numerous, are nevertheless important. Several historians theorize that the Tel Shalem arch depicted a major battle between Roman armies and Bar Kokhba's rebels in Bet Shean valley, thus extending the battle areas some 50 km northwards from Judea. The 2013 discovery of the military camp of Legio VI Ferrata near Tel Megiddo,[80] and ongoing excavations there may shed light to extension of the rebellion to the northern valleys. A 2015 archaeological survey in Samaria identified some 40 hideout cave systems from the period, some containing Bar Kokhba's minted coins, suggesting that the war raged in Samaria at high intensity.[47] There is also evidence to support war operations on the coastal plain and as far as Transjordan. The fact that Galilee retained its Jewish character after the end of the revolt has been taken as an indication by some that either the revolt was never joined by Galilee or that the rebellion was crushed relatively early there compared to Judea.[81]

Until 1951, Bar Kokhba Revolt coinage was the sole archaeological evidence for dating the revolt.[7] These coins include references to "Year One of the redemption of Israel", "Year Two of the freedom of Israel", and "For the freedom of Jerusalem". Despite the reference to Jerusalem, recent archaeological finds, and the lack of revolt coinage found in Jerusalem, supports the view that the revolt did not capture Jerusalem.[82]

Sources

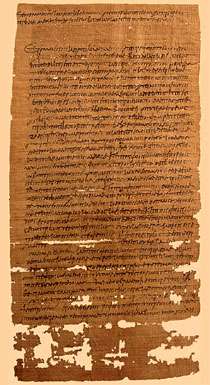

The revolt is mostly still shrouded in mystery, and only one brief historical account of the rebellion survives.[7] The best recognized source for the revolt is Cassius Dio, Roman History (book 69),[3][83] even though the writings of the Roman historian concerning the Bar Kokhba revolt survived only as fragments. The Jerusalem Talmud contains descriptions of the results of the rebellion, including the Roman executions of Judean leaders. The discovery of the Cave of Letters in the Dead Sea area, dubbed as "Bar Kokhba archive",[84] which contained letters actually written by Bar Kokhba and his followers, has added much new primary source data, indicating among other things that there was a pronounced foreign contingent among Bar Kokhba's forces, accounted for by the fact that his military correspondence was, in part, conducted in Greek.[85] Several more brief sources have been uncovered in the area over the past century, including references to the revolt from Nabatea and Roman Syria. Roman inscriptions in Tel Shalem, Betar fortress, Jerusalem and other locations also contribute to the current historical understanding of the Bar Kokhba War.

Archaeology

Destroyed Jewish villages and fortresses

Several archaeological surveys have been performed during the 20th and 21st centuries in ruins of Jewish villages across Judea and Samaria, as well in the Roman-dominated cities on the Israeli coastal plain.

Betar fortress

The ruins of Betar, the last fortress of Bar Kokhba, destroyed by Hadrian's legions in 135 CE, is located in the vicinity of the towns of Battir and Beitar Illit. A stone inscription bearing Latin characters and discovered near Betar shows that the Fifth Macedonian Legion and the Eleventh Claudian Legion took part in the siege.[86]

Hideout systems

Cave of Letters

The Cave of Letters was surveyed in explorations conducted in 1960-61, when letters and fragments of papyri were found dating back to the period of the Bar Kokhba revolt. Some of these were personal letters between Bar Kokhba and his subordinates, and one notable bundle of papyri, known as the Babata or Babatha cache, revealed the life and trials of a woman, Babata, who lived during this period.

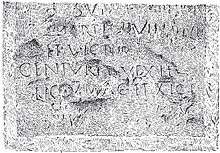

Jerusalem inscription dedicated to Hadrian (129/30 CE)

In 2014, one half of a Latin inscription was discovered in Jerusalem during excavations near the Damascus Gate.[87] It was identified as the right half of a complete inscription, the other part of which was discovered nearby in the late 19th century and is currently on display in the courtyard of Jerusalem's Studium Biblicum Franciscanum Museum. The complete inscription was translated as follows:

- To the Imperator Caesar Traianus Hadrianus Augustus, son of the deified Traianus Parthicus, grandson of the deified Nerva, high priest, invested with tribunician power for the 14th time, consul for the third time, father of the country (dedicated by) the 10th legion Fretensis Antoniniana.

The inscription was dedicated by Legio X Fretensis to the emperor Hadrian in the year 129/130 CE. The inscription is considered to greatly strengthen the claim that indeed the emperor visited Jerusalem that year, supporting the traditional claim that Hadrian's visit was among the main causes of the Bar Kokhba Revolt, and not the other way around.[87]

See also

- List of conflicts in the Near East

- Sicaricon (Jewish law)

References

- "Legio VIIII Hispana". livius.org. Retrieved 2014-06-26.

- Mor, M. The Second Jewish Revolt: The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Brill, 2016. p334.

- Cassius Dio, Translation by Earnest Cary. Roman History, book 69, 12.1-14.3. Loeb Classical Library, 9 volumes, Greek texts and facing English translation: Harvard University Press, 1914 thru 1927. Online in LacusCurtius: and livius.org:. Book scan in Internet Archive:.

- for the year 136, see: W. Eck, The Bar Kokhba Revolt: The Roman Point of View, pp. 87–88.

- William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period, Cambridge University Press, 1984 pp. 106.

- Hanan Eshel, 'The Bar Kochba revolt, 132-135,' in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, pp.105-127, p.105.

- William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein: The Cambridge History of Judaism: The late Roman-Rabbinic period, p. 35, Cambridge University Press, 1984, ISBN 9780521772488

- Axelrod, Alan (2009). Little-Known Wars of Great and Lasting Impact. Fair Winds Press. p. 29. ISBN 9781592333752.

- John S. Evans (2008). The Prophecies of Daniel 2.

Known as the Bar Kokhba Revolt, after its charismatic leader, Simon Bar Kokhba, whom many Jews regarded as their promised messiah

- "Israel Tour Daily Newsletter". 27 July 2010. Archived from the original on 16 June 2011.

- Taylor, J. E. The Essenes, the Scrolls, and the Dead Sea. Oxford University Press.

Up until this date the Bar Kokhba documents indicate that towns, villages and ports where Jews lived were busy with industry and activity. Afterwards there is an eerie silence, and the archaeological record testifies to little Jewish presence until the Byzantine era, in En Gedi. This picture coheres with what we have already determined in Part I of this study, that the crucial date for what can only be described as genocide, and the devastation of Jews and Judaism within central Judea, was 135 CE and not, as usually assumed, 70 CE, despite the siege of Jerusalem and the Temple's destruction

- Mor, M. The Second Jewish Revolt: The Bar Kokhba War, 132-136 CE. Brill, 2016. P471/

- Totten, S. Teaching about genocide: issues, approaches and resources. p24.

- David Goodblatt, 'The political and social history of the Jewish community in the Land of Israel,' in William David Davies, Louis Finkelstein, Steven T. Katz (eds.) The Cambridge History of Judaism: Volume 4, The Late Roman-Rabbinic Period, Cambridge University Press, 2006 pp.404-430, p.406.

- L. J. F. Keppie (2000) Legions and veterans: Roman army papers 1971-2000 Franz Steiner Verlag, ISBN 3-515-07744-8 pp 228–229

- livius.org account(Legio XXII Deiotariana)

- H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, Harvard University Press, 1976, ISBN 0-674-39731-2, page 334: "In an effort to wipe out all memory of the bond between the Jews and the land, Hadrian changed the name of the province from Judaea to Syria-Palestina, a name that became common in non-Jewish literature."

- Ariel Lewin. The archaeology of Ancient Judea and Palestine. Getty Publications, 2005 p. 33. "It seems clear that by choosing a seemingly neutral name - one juxtaposing that of a neighboring province with the revived name of an ancient geographical entity (Palestine), already known from the writings of Herodotus - Hadrian was intending to suppress any connection between the Jewish people and that land." ISBN 0-89236-800-4

- The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered by Peter Schäfer, ISBN 3-16-148076-7

- Feldman 1990, p. 19: "While it is true that there is no evidence as to precisely who changed the name of Judaea to Palestine and precisely when this was done, circumstantial evidence would seem to point to Hadrian himself, since he is, it would seem, responsible for a number of decrees that sought to crush the national and religious spirit of thejews, whether these decrees were responsible for the uprising or were the result of it. In the first place, he refounded Jerusalem as a Graeco-Roman city under the name of Aelia Capitolina. He also erected on the site of the Temple another temple to Zeus."

- Jacobson 2001, p. 44–45: "Hadrian officially renamed Judea Syria Palaestina after his Roman armies suppressed the Bar-Kokhba Revolt (the Second Jewish Revolt) in 135 C.E.; this is commonly viewed as a move intended to sever the connection of the Jews to their historical homeland. However, that Jewish writers such as Philo, in particular, and Josephus, who flourished while Judea was still formally in existence, used the name Palestine for the Land of Israel in their Greek works, suggests that this interpretation of history is mistaken. Hadrian’s choice of Syria Palaestina may be more correctly seen as a rationalization of the name of the new province, in accordance with its area being far larger than geographical Judea. Indeed, Syria Palaestina had an ancient pedigree that was intimately linked with the area of greater Israel."

- M. Avi-Yonah, The Jews under Roman and Byzantine Rule, Jerusalem 1984 p. 143

- Justin, "Apologia", ii.71, compare "Dial." cx; Eusebius "Hist. Eccl." iv.6,§2; Orosius "Hist." vii.13

- Davidson, Linda (2002). Pilgrimage: From the Ganges to Graceland: an Encyclopedia, Volume 1. ABC-CLIO. p. 279. ISBN 1576070042.

- "Ancient Inscription Identifies Gargilius Antiques as Roman Ruler on Eve of Bar Kochva Revolt". The Jewish Press. December 1, 2016.

- Schäfer, Peter (2003). The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest. Translated by David Chowcat. Routledge. p. 146.

- See Platner, Samuel Ball (1929). "Pomerium". A Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome – via LacusCurtius. Gates, Charles (2011). Ancient Cities: The Archaeology of Urban Life in the Ancient Near East and Egypt, Greece and Rome. Taylor & Francis. p. 335. ISBN 9781136823282 – via Google books.

- The Mishnah has a segment: "[O]n the 9th of Ab...and the city was ploughed up." on mas. Taanith, Chapter 4, Mishnah no. 6. See:

- Blackman, Philip, ed. (1963). MISHNAYOTH, VOLUME II, ORDER MOED (in Hebrew and English). New York: Judaica. p. 432 – via HebrewBooks.

- Greenup, Albert William (1921). The Mishna tractate Taanith (On the public fasts). London: [Palestine House]. p. 32 – via Internet Archive.

- Sola, D. A.; Raphall, M. J., eds. (1843). "XX. Treatise Taanith, chapter IV, §6.". Eighteen Treatises from the Mishna – via Internet Sacred Text Archive.

- The Babylonian Talmud and Jerusalem Talmud both explicate the segment refers to Rufus:

Babylonian: mas. Taanith 29a. See

- "Shas Soncino: Taanith 29a". dTorah.com. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- "Bab. Taanith; ch.4.1-8, 26a-31a". RabbinicTraditions. Retrieved 2014-06-28.

- "Ta'anis 2a-31a" (PDF). Soncino Babylonian Talmud. Translated by I Epstein. Halakhah.com. pp. 92–93. Retrieved 2014-06-27.

AND THE CITY WAS PLOUGHED UP. It has been taught: When Turnus Rufus the wicked destroyed[note 20: Var lec.: ‘ploughed’.] the Temple,...

CS1 maint: others (link).

- The Jerusalem Talmud relates it to the Temple, Taanith 25b:

- "דף כה,ב פרק ד". Mechon Mamre (in Hebrew). הלכה ה גמרא.

ונחרשה העיר. חרש רופוס שחיק עצמות את ההיכל

- (in Hebrew) – via Wikisource.

- "דף כה,ב פרק ד". Mechon Mamre (in Hebrew). הלכה ה גמרא.

- "Roman provincial coin of Hadrian [image]". Israel Museum. Archived from the original on 2014-07-02. Retrieved 2014-07-01 – via Europeana.

- Boatwright, Mary Taliaferro (2003). Hadrian and the Cities of the Roman Empire. Princeton University Press. p. 199. ISBN 0691094934.

- Metcalf, William (2012-02-23). The Oxford Handbook of Greek and Roman Coinage. Oxford University Press. p. 492. ISBN 9780195305746.

- Benjamin H. Isaac, Aharon Oppenheimer, 'The Revolt of Bar Kochba:Ideology and Modern Scholarship,' in Benjamin H. Isaac, The Near East Under Roman Rule: Selected Papers , BRILL (Volume 177 of Mnemosyne, bibliotheca classica Batava. 177: Supplementum), 1998 pp.220-252, 226-227

- Aharon Oppenheimer, 'The Ban on Circumcision as a cause of the Revolt: A Reconsideration,' in Peter Schäfer (ed.) The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest, Mohr Siebeck 2003 pp.55-69 pp.55f.

- Craig A. Evans, Jesus and His Contemporaries: Comparative Studies, BRILL 2001 p.185:'moverunt ea tempestate et Iudaei bellum, quod vetabantur mutilare genitalia.'

- Aharon Oppenheimer, ‘The Ban on Circumcision as a Cause of the Revolt: A Reconsideration,’ Aharon Oppenheimer, Between Rome and Babylon, Mohr Siebeck 2005 pp.243-254 pp.

- Schäfer, Peter (1998). Judeophobia: Attitudes Toward the Jews in the Ancient World. Harvard University Press. pp. 103–105. ISBN 9780674043213. Retrieved 2014-02-01.

[...] Hadrian's ban on circumcision, allegedly imposed sometime between 128 and 132 CE [...]. The only proof for Hadrian's ban on circumcision is the short note in the Historia Augusta: 'At this time also the Jews began war, because they were forbidden to mutilate their genitals (quot vetabantur mutilare genitalia). [...] The historical credibility of this remark is controversial [...] The earliest evidence for circumcision in Roman legislation is an edict by Antoninus Pius (138-161 CE), Hadrian's successor [...] [I]t is not utterly impossible that Hadrian [...] indeed considered circumcision as a 'barbarous mutilation' and tried to prohibit it. [...] However, this proposal cannot be more than a conjecture, and, of course, it does not solve the questions of when Hadrian issued the decree (before or during/after the Bar Kokhba war) and whether it was directed solely against Jews or also against other peoples.

- Christopher Mackay, Ancient Rome a Military and Political History Cambridge University Press 2007 p.230

- Peter Schäfer, The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome, Mohr Siebeck 2003. p.68

- Peter Schäfer, The History of the Jews in the Greco-Roman World: The Jews of Palestine from Alexander the Great to the Arab Conquest, Routledge, 2003 p. 146.

- Gilad, Elon (6 May 2015). "The Bar Kochba Revolt: A Disaster Celebrated by Zionists on Lag Ba'Omer". Haaretz. Retrieved 14 May 2019.

- Numbers 24:17: There shall come a star out of Jacob, and a sceptre shall rise out of Israel, and shall smite the corners of Moab, and destroy all the children of Sheth.

- Krauss, S. (1906). "BAR KOKBA AND BAR KOKBA WAR". In Singer, Isidore (ed.). The Jewish Encyclopedia. 2. pp. 506–507.

Bar Kokba, the hero of the third war against Rome, appears under this name only among ecclesiastical writers: heathen authors do not mention him; and Jewish sources call him Ben (or Bar) Koziba or Kozba...

- Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. p184

- Hebrew: התגלית שהוכיחה: מרד בר כוכבא חל גם בשומרון NRG. 15 July 2015.

- Mohr Siebek et al. Edited by Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. P172.

- Charles Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873-1874, London 1899, pp. 463-470

- Jerusalem Talmud Ta'anit iv. 68d; Lamentations Rabbah ii. 2

- Jerusalem Talmud, Taanit 4:5 (24a); Midrash Rabba (Lamentations Rabba 2:5).

- Ta'anit 4:5

- Martyrs, The Ten Jewish Encyclopedia: "The fourth martyr was Hananiah ben Teradion, who was wrapped in a scroll of the Law and placed on a pyre of green brushwood; to prolong his agony, wet wool was placed on his chest."

- Mohr Siebek et al. Edited by Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. P160. "Thus it is very likely that the revolt ended only in early 136."

- "Mosaic or mosaic?—The Genesis of the Israeli Language" by Zuckermann, Gilad

- Schäfer, P. (1981). Der Bar Kochba-Aufstand. Tübingen. pp. 131ff.

- Mohr Siebek et al. Edited by Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. P142-3.

- "Texts on Bar Kochba: Eusebius".

- Bourgel, Jonathan, ″The Jewish-Christians in the storm of the Bar Kokhba Revolt″, in: From One Identity to Another: The Mother Church of Jerusalem Between the Two Jewish Revolts Against Rome (66-135/6 EC). Paris: Éditions du Cerf, collection Judaïsme ancien et Christianisme primitive, (French), pp. 127-175.

- Cassius Dio, Roman History

- E. Werner. The bar Kokhba Revolt: The Roman Point of View. The Journal of Roman Studies Vol. 89 (1999), pp. 76-89.

- "Legio VIIII Hispana".

- H.H. Ben-Sasson, A History of the Jewish People, page 334: "Jews were forbidden to live in the city and were allowed to visit it only once a year, on the Ninth of Ab, to mourn on the ruins of their holy Temple."

- Miller, 1984, p. 132

- Willem F. Smelik, The Targum of Judges, BRILL 1995 p.434.

- Bernard Lazare and Robert Wistrich, Antisemitism: Its History and Causes, University of Nebraska Press, 1995, I, pp.46-7.

- Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, 23.1.2–3.

- See "Julian and the Jews 361–363 CE" (Fordham University, The Jesuit University of New York) and "Julian the Apostate and the Holy Temple".

- A Psychoanalytic History of the Jews, Avner Falk

- Avraham Yaari, Igrot Eretz Yisrael (Tel Aviv, 1943), p. 46.

- "Remains of the Jews".

- Shalev-Hurvitz, V. Oxford University Press 2015. p235

- Weinberger, p. 143

- Brewer, C. 2005. p.127

- Evans, J.A.S. 2005. "Jews and Samaritans"

- Edward Lipiński (2004). Itineraria Phoenicia. Peeters Publishers. pp. 542–543. Retrieved 11 March 2014.

- ""

- Wikisource: "Epistle to Yemen"

- The military and militarism in Israeli society by Edna Lomsky-Feder, Eyal Ben-Ari]." Retrieved on September 3, 2010

- "Roman Legion Camp Unearthed in Megiddo - Inside Israel - News - Arutz Sheva". Arutz Sheva. Retrieved 2016-03-02.

- Yehoshafat Harkabi (1983). The Bar Kokhba Syndrome: Risk and Realism in International Politics. SP Books. pp. 1–. ISBN 978-0-940646-01-8.

- Eshel 2003, pp. 95–96: "Returning to the Bar Kokhba revolt, we should note that up until the discovery of the first Bar Kokhba documents in Wadi Murabba'at in 1951, Bar Kokhba coins were the sole archaeological evidence available for dating the revolt. Based on coins overstock by the Bar Kokhba administration, scholars dated the beginning of the Bar Kokhba regime to the conquest of Jerusalem by the rebels. The coins in question bear the following inscriptions: "Year One of the redemption of Israel", "Year Two of the freedom of Israel", and "For the freedom of Jerusalem". Up until 1948 some scholars argued that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins predated the others, based upon their assumption that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the rebel capture Jerusalem." L. Mildenberg's study of the dies of the Bar Kokhba definitely established that the "Freedom of Jerusalem" coins were struck later than the ones inscribed "Year Two of the freedom of Israel". He dated them to the third year of the revolt.' Thus, the view that the dating of the Bar Kokhba regime began with the conquest of Jerusalem is untenable. lndeed, archeological finds from the past quarter-century, and the absence of Bar Kokhba coins in Jerusalem in particular, support the view that the rebels failed to take Jerusalem at all."

- Mordechai, Gihon. New insight into the Bar Kokhba War and a reappraisal of Dio Cassius 69.12-13. University of Pennsylvania Press. The Jewish Quarterly Review Vol. 77, No. 1 (Jul., 1986), pp. 15-43. doi:10.2307/1454444

- Peter Schäfer. The Bar Kokhba War reconsidered. 2003. p184.

- Mordechai Gichon, 'New Insight into the Bar Kokhba War and a Reappraisal of Dio Cassius 69.12-13,' The Jewish Quarterly Review, Vol. 77, No. 1 (Jul., 1986), pp. 15-43, p.40.

- C. Clermont-Ganneau, Archaeological Researches in Palestine during the Years 1873-74, London 1899, pp. 263-270.

- Jerusalem Post. 21 October 2014 WATCH: 2,000-YEAR-OLD INSCRIPTION DEDICATED TO ROMAN EMPEROR UNVEILED IN JERUSALEM

Further reading

- Eshel, Hanan (2003). "The Dates used during the Bar Kokhba Revolt". In Peter Schäfer (ed.). The Bar Kokhba War Reconsidered: New Perspectives on the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Mohr Siebeck. pp. 95–96. ISBN 978-3-16-148076-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Yohannan Aharoni & Michael Avi-Yonah, The MacMillan Bible Atlas, Revised Edition, pp. 164–65 (1968 & 1977 by Carta Ltd.)

- The Documents from the Bar Kokhba Period in the Cave of Letters (Judean Desert studies). Jerusalem: Israel Exploration Society, 1963–2002.

- Vol. 2, "Greek Papyri", edited by Naphtali Lewis; "Aramaic and Nabatean Signatures and Subscriptions", edited by Yigael Yadin and Jonas C. Greenfield. (ISBN 9652210099).

- Vol. 3, "Hebrew, Aramaic and Nabatean–Aramaic Papyri", edited Yigael Yadin, Jonas C. Greenfield, Ada Yardeni, BaruchA. Levine (ISBN 9652210463).

- W. Eck, 'The Bar Kokhba Revolt: the Roman point of view' in the Journal of Roman Studies 89 (1999) 76ff.

- Peter Schäfer (editor), Bar Kokhba reconsidered, Tübingen: Mohr: 2003

- Aharon Oppenheimer, 'The Ban of Circumcision as a Cause of the Revolt: A Reconsideration', in Bar Kokhba reconsidered, Peter Schäfer (editor), Tübingen: Mohr: 2003

- Faulkner, Neil. Apocalypse: The Great Jewish Revolt Against Rome. Stroud, Gloucestershire, UK: Tempus Publishing, 2004 (hardcover, ISBN 0-7524-2573-0).

- Goodman, Martin. The Ruling Class of Judaea: The Origins of the Jewish Revolt against Rome, A.D. 66–70. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1987 (hardcover, ISBN 0-521-33401-2); 1993 (paperback, ISBN 0-521-44782-8).

- Richard Marks: The Image of Bar Kokhba in Traditional Jewish Literature: False Messiah and National Hero: University Park: Pennsylvania State University Press: 1994: ISBN 0-271-00939-X

- David Ussishkin: "Archaeological Soundings at Betar, Bar-Kochba's Last Stronghold", in: Tel Aviv. Journal of the Institute of Archaeology of Tel Aviv University 20 (1993) 66ff.

- Yadin, Yigael. Bar-Kokhba: The Rediscovery of the Legendary Hero of the Second Jewish Revolt Against Rome. New York: Random House, 1971 (hardcover, ISBN 0-394-47184-9); London: Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1971 (hardcover, ISBN 0-297-00345-3).

- Mildenberg, Leo. The Coinage of the Bar Kokhba War. Switzerland: Schweizerische Numismatische Gesellschaft, Zurich, 1984 (hardcover, ISBN 3-7941-2634-3).

External links

- Wars between the Jews and Romans: Simon ben Kosiba (130-136 CE), with English translations of sources.

- Photographs from Yadin's book Bar Kokhba

- Archaeologists find tunnels from Jewish revolt against Romans by the Associated Press. Haaretz March 13, 2006

- Bar Kokba and Bar Kokba War Jewish Encyclopedia