Circle of fifths

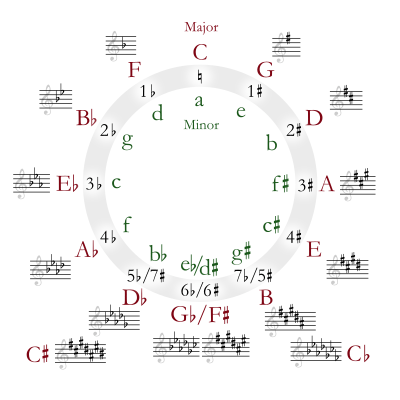

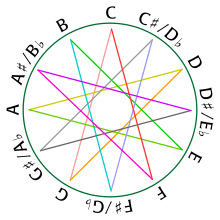

In music theory, the circle of fifths (or circle of fourths) is the relationship among the 12 tones (or pitches) of the chromatic scale, their corresponding key signatures, and the associated major and minor keys. More specifically, it is a geometrical representation of relationships among the 12 pitch classes of the chromatic scale in pitch class space.

Definition

The term "fifth" defines an interval or mathematical ratio, which is the closest and most consonant non-octave interval. The circle of fifths is a sequence of pitches or key tonalities, represented as a circle, in which the next pitch (turning clockwise) is found seven semitones higher than the last. Musicians and composers use the circle of fifths to understand and describe the musical relationships among some selection of those pitches. The circle's design is helpful in composing and harmonizing melodies, building chords, and modulating to different keys within a composition.[1]

At the top of the circle, the key of C Major has no sharps or flats. Starting from the apex and proceeding clockwise by ascending fifths, the key of G has one sharp, the key of D has 2 sharps, and so on. Similarly, proceeding counterclockwise from the apex by descending fifths, the key of F has one flat, the key of B♭ has 2 flats, and so on. At the bottom of the circle, the sharp and flat keys overlap, showing pairs of enharmonically equivalent key signatures.

Starting at any pitch, ascending by the interval of an equal tempered fifth, one passes all twelve tones clockwise, to return to the beginning pitch class. To pass the twelve tones counterclockwise, it is necessary to ascend by perfect fourths, rather than fifths. (To the ear, the sequence of fourths gives an impression of settling, or resolution; see cadence.)

Structure and use

Pitches within the chromatic scale are related not only by the number of semitones between them within the chromatic scale, but also related harmonically within the circle of fifths. Moving counterclockwise the direction of the circle of fifths gives the circle of fourths. Typically the "circle of fifths" is used in the analysis of classical music, whereas the "circle of fourths" is used in the analysis of jazz music, but this distinction is not exclusive. The "circle of fifths" is a requirement in the barbershop style as the Barbershop Harmony Society's Contest and Judging Handbook says the barbershop style consists of "seventh chords that often resolve around the circle of fifths, while also making use of other resolutions", among other requirements.

Diatonic key signatures

The circle is commonly used to represent the relationship between diatonic scales. Here, the letters on the circle are taken to represent the major scale with that note as tonic. The numbers on the inside of the circle show how many sharps or flats the key signature for this scale has. Thus a major scale built on A has 3 sharps in its key signature. The major scale built on F has 1 flat.

For minor scales, rotate the letters counter-clockwise by 3, so that, e.g., A minor has 0 sharps or flats and E minor has 1 sharp. (See relative key for details.) A way to describe this phenomenon is that, for any major key [e.g. G major, with one sharp (F♯) in its diatonic scale], a scale can be built beginning on the sixth (VI) degree (relative minor key, in this case, E) containing the same notes, but from E–E as opposed to G–G. Or, G-major scale (G–A–B–C–D–E–F♯–G) is enharmonic (harmonically equivalent) to the e-minor scale (E–F♯–G–A–B–C–D–E).

When notating the key signatures, the order of sharps that are found at the beginning of the staff line follows the circle of fifths from F through B. The order is F, C, G, D, A, E, B. If there is only one sharp, such as in the key of G major, then the one sharp is F sharp. If there are two sharps, the two are F and C, and they appear in that order in the key signature. The order of sharps goes clockwise around the circle of fifths. (For major keys, the last sharp is on the seventh scale degree. The tonic (key note) is one half-step above the last sharp.)

For notating flats, the order is reversed: B, E, A, D, G, C, F. This order runs counter-clockwise along the circle of fifths; in other words they progress by fourths. Following the major keys from the key of F to the key of C flat (B) counter-clockwise around the circle of fifths, as each key signature adds a flat, the flats always occur in this order. (For major keys, the penultimate (second to last) flat in the key signature is on the tonic. With only one flat, the key of F does not follow this pattern.)

Modulation and chord progression

Tonal music often modulates by moving between adjacent scales on the circle of fifths. This is because diatonic scales contain seven pitch classes that are contiguous on the circle of fifths. It follows that diatonic scales a perfect fifth apart share six of their seven notes. Furthermore, the notes not held in common differ by only a semitone. Thus modulation by perfect fifth can be accomplished in an exceptionally smooth fashion. For example, to move from the C major scale F–C–G–D–A–E–B to the G major scale C–G–D–A–E–B–F♯, one need only move the C major scale's "F" to "F♯".

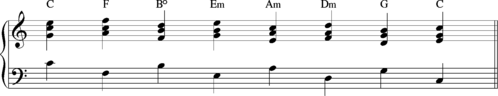

The circle can be easily used to find out the common chord progression for basic keys. The circle of fifths shows every major key with its corresponding minor key (of the Aeolian mode). This can be used as the vi chord in a progression. The V and IV chord can be found by moving clockwise and counterclockwise from the root chord respectively. The corresponding minor keys of the V and IV are the iii and ii respectively.

The major and minor chords in each major key:

Chord Key |

I | ii | iii | IV | V | vi |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C major | C | Dm | Em | F | G | Am |

| G major | G | Am | Bm | C | D | Em |

| D major | D | Em | F♯m | G | A | Bm |

| A major | A | Bm | C♯m | D | E | F♯m |

| E major | E | F♯m | G♯m | A | B | C♯m |

| B major | B | C♯m | D♯m | E | F♯ | G♯m |

| F♯ major | F♯ | G♯m | A♯m | B | C♯ | D♯m |

| C♯ major | C♯ | D♯m | E♯m | F♯ | G♯ | A♯m |

| C♭ major | C♭ | D♭m | E♭m | F♭ | G♭ | A♭m |

| G♭ major | G♭ | A♭m | B♭m | C♭ | D♭ | E♭m |

| D♭ major | D♭ | E♭m | Fm | G♭ | A♭ | B♭m |

| A♭ major | A♭ | B♭m | Cm | D♭ | E♭ | Fm |

| E♭ major | E♭ | Fm | Gm | A♭ | B♭ | Cm |

| B♭ major | B♭ | Cm | Dm | E♭ | F | Gm |

| F major | F | Gm | Am | B♭ | C | Dm |

In Western tonal music, one also finds chord progressions between chords whose roots are related by perfect fifth. For instance, root progressions such as D–G–C are common. For this reason, the circle of fifths can often be used to represent "harmonic distance" between chords.

According to theorists including Goldman, harmonic function (the use, role, and relation of chords in harmony), including "functional succession", may be "explained by the circle of fifths (in which, therefore, scale degree II is closer to the dominant than scale degree IV)".[2] In this view the tonic is considered the end of the line towards which a chord progression derived from the circle of fifths progresses.

According to Goldman's Harmony in Western Music, "the IV chord is actually, in the simplest mechanisms of diatonic relationships, at the greatest distance from I. In terms of the [descending] circle of fifths, it leads away from I, rather than toward it."[3] Thus the progression I–ii–V–I (an authentic cadence) would feel more final or resolved than I–IV–I (a plagal cadence). Goldman[4] concurs with Nattiez, who argues that "the chord on the fourth degree appears long before the chord on II, and the subsequent final I, in the progression I–IV–viio–iii–vi–ii–V–I", and is farther from the tonic there as well.[5] (In this and related articles, upper-case Roman numerals indicate major triads while lower-case Roman numerals indicate minor triads.)

Goldman argues that "historically the use of the IV chord in harmonic design, and especially in cadences, exhibits some curious features. By and large, one can say that the use of IV in final cadences becomes more common in the nineteenth century than it was in the eighteenth, but that it may also be understood as a substitute for the ii chord when it precedes V. It may also be quite logically construed as an incomplete ii7 chord (lacking root)."[3] The delayed acceptance of the IV–I in final cadences is explained aesthetically by its lack of closure, caused by its position in the circle of fifths. The earlier use of IV–V–I is explained by proposing a relation between IV and ii, allowing IV to substitute for or serve as ii. However, Nattiez calls this latter argument "a narrow escape: only the theory of a ii chord without a root allows Goldman to maintain that the circle of fifths is completely valid from Bach to Wagner", or the entire common practice period.[5]

Circle closure in non-equal tuning systems

When an instrument is tuned with the equal temperament system, the width of the fifths is such that the circle "closes". This means that ascending by twelve fifths from any pitch, one returns to a tone exactly in the same pitch class as the initial tone, and exactly seven octaves above it. To obtain such a perfect circle closure, the fifth is slightly flattened with respect to its just intonation (3:2 interval ratio).

Thus, ascending by justly tuned fifths fails to close the circle by an excess of approximately 23.46 cents, roughly a quarter of a semitone, an interval known as the Pythagorean comma. In Pythagorean tuning, this problem is solved by markedly shortening the width of one of the twelve fifths, which makes it severely dissonant. This anomalous fifth is called wolf fifth as a humorous metaphor of the unpleasant sound of the note (like a wolf trying to howl an off-pitch note). The quarter-comma meantone tuning system uses eleven fifths slightly narrower than the equally tempered fifth, and requires a much wider and even more dissonant wolf fifth to close the circle. More complex tuning systems based on just intonation, such as 5-limit tuning, use at most eight justly tuned fifths and at least three non-just fifths (some slightly narrower, and some slightly wider than the just fifth) to close the circle. Other tuning systems use up to 53 tones (the original 12 tones and 42 more between them) in order to close the circle of fifths.

In lay terms

| Playing the circle of fifths | |

|---|---|

1 octave, fourths, descending 1 octave, fifths, ascending 2 octave, fifths, ascending 2 octave, fourths, descending 2 octave, fourths, ascending 2 octave, fifths, descending  multi octave, fifths, ascending  multi octave, fourths, descending  multi octave, fourths, ascending |

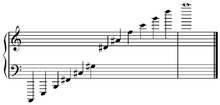

A simple way to see the musical interval known as a fifth is by looking at a piano keyboard, and, starting at any key, counting seven keys to the right (both black and white, not including the first) to get to the next note on the circle shown above. Seven half steps, the distance from the 1st to the 8th key on a piano is a "perfect fifth", called 'perfect' because it is neither major nor minor, but applies to both major and minor scales and chords, and a 'fifth' because, although it is a distance of seven semitones on a keyboard, it spans five adjacent notes in the major or minor scale.

A simple way to hear the relationship between these notes is by playing them on a piano keyboard. When traversing the circle of fifths backwards, the notes will feel as though they fall into each other. This aural relationship is what the mathematics describe.

Perfect fifths may be justly tuned or tempered. Two notes whose frequencies differ by a ratio of 3:2 make the interval known as a justly tuned perfect fifth. Cascading twelve such fifths does not return to the original pitch class after going round the circle, so the 3:2 ratio may be slightly detuned, or tempered. Temperament allows perfect fifths to cycle, and allows pieces to be transposed, or played in any key on a piano or other fixed-pitch instrument without distorting their harmony. The primary tuning system used for Western (especially keyboard and fretted) instruments today, twelve-tone equal temperament, uses an irrational multiplier, 21/12, to calculate the frequency difference of a semitone. An equal-tempered fifth, at a frequency ratio of 27/12:1 (or about 1.498307077:1) is approximately two cents narrower than a justly tuned fifth at a ratio of 3:2.

History

There are sources that imply that Pythagoras, the ancient Greek philosopher from the sixth century B.C. invented the circle of fifths, but they do not provide proof of this claim.[6][7][8] Pythagoras was primarily concerned with the theoretical science of harmonics and is credited with having devised a system of tuning based upon the interval of a fifth, but did not tune more than eight notes, and left no written records of his work.[9]

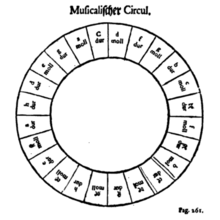

In the late 1670s a treatise called Grammatika was written by the Ukrainian composer and theorist Nikolay Diletsky. Diletsky’s Grammatika is a treatise on composition, "the first of its kind, aimed at teaching a Russian audience how to write Western-style polyphonic compositions." It taught how to write kontserty, polyphonic a cappella works normally based on liturgical texts and created by putting together musical sections that have contrasting rhythm, meters, melodic material and vocal groupings. Diletsky intended his treatise to be a guide to composition but pertaining to the rules of music theory.

Within the Grammatika treatise is where the first circle of fifths appeared and was used for students as a composer's tool.[10]

Use

In musical pieces from the Baroque music era and the Classical era of music and in Western popular music, traditional music and folk music, when pieces or songs modulate to a new key, these modulations are often associated with the circle of fifths.

In practice, compositions rarely make use of the entire circle of fifths. More commonly, composers make use of “the compositional idea of the ‘cycle’ of 5ths, when music moves consistently through a smaller or larger segment of the tonal structural resources which the circle abstractly represents.”[11] The usual practice is to derive the circle of fifths progression from the seven tones of the diatonic scale, rather from the full range of twelve tones present in the chromatic scale. In this diatonic version of the circle, one of the fifths is not a true fifth: it is a tritone (or a diminished fifth), e.g. between F and B in the "natural" diatonic scale (i.e. without sharps or flats). Here is how the circle of fifths derives, through permutation from the diatonic major scale:

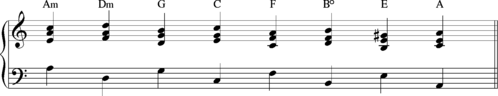

And from the (natural) minor scale:

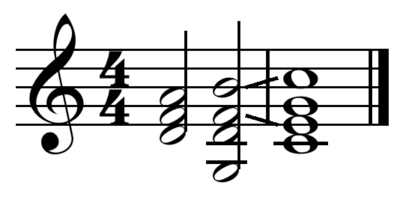

The following is the basic sequence of chords that can be built over the major bass-line:

And over the minor:

Adding sevenths to the chords creates a greater sense of forward momentum to the harmony:

Baroque era

According to Richard Taruskin, Arcangelo Corelli was the most influential composer to establish the pattern as a standard harmonic ”trope”: “It was precisely in Corelli’s time, the late seventeenth century, that the circle of fifths was being ‘theorized’ as the main propellor of harmonic motion, and it was Corelli more than any one composer who put that new idea into telling practice.”[12]

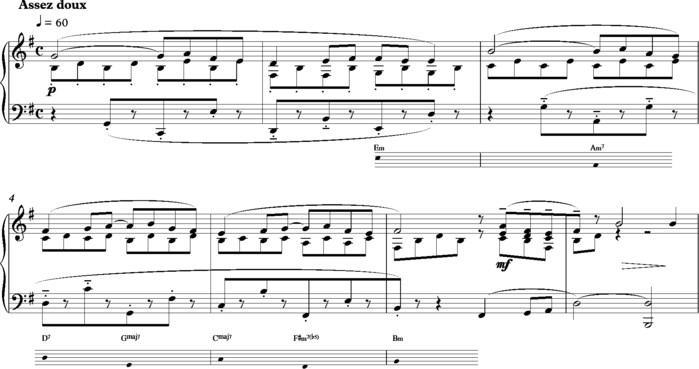

The circle of fifths progression occurs frequently in the music of J. S. Bach. In the following, from Jauchzet Gott in allen Landen, BWV 51, even when the solo bass line implies rather than states the chords involved:

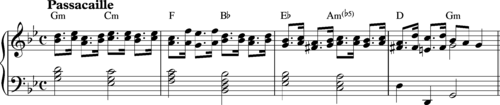

Handel uses a circle of fifths progression as the basis for the Passacaglia movement from his Harpsichord suite No. 6 in G minor.

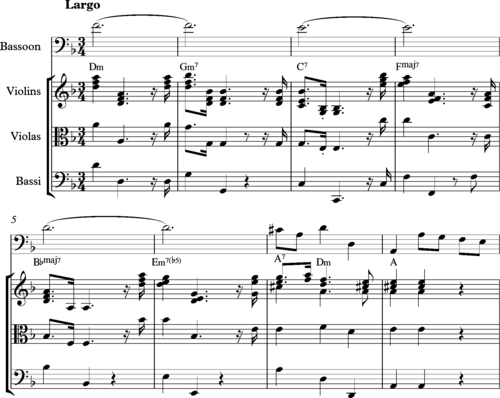

Baroque composers learnt to enhance the “propulsive force” of the harmony engendered by the circle of fifths “by adding sevenths to most of the constituent chords.” “These sevenths, being dissonances, create the need for resolution, thus turning each progression of the circle into a simultaneous reliever and re-stimulator of harmonic tension... Hence harnessed for expressive purposes.” [13] Striking passages that illustrate the use of sevenths occur in the aria “Pena tiranna” in Handel’s 1715 opera Amadigi di Gaula :

– and in Bach's keyboard arrangement of Alessandro Marcello's Concerto for Oboe and Strings.

.png)

Nineteenth century

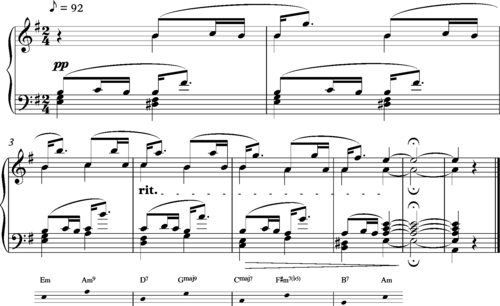

During the nineteenth century, composers made use of the circle of fifths to enhance the expressive character of their music. Franz Schubert’s poignant Impromptu in E flat major, D899, contains such a passage:

– as does the Intermezzo movement from Mendelssohn’s String Quartet No.2:

.png)

Robert Schumann’s evocative “Child falling asleep” from his Kinderszenen springs a surprise at the end of the progression: the piece ends on an A minor chord, instead of the expected tonic E minor.

In Wagner’s opera, Götterdämmerung, a cycle of fifths progression occurs in the music which transitions from the end of the prologue into the first scene of Act 1, set in the imposing hall of the wealthy Gibichungs. “Status and reputation are written all over the motifs assigned to Gunther”,[14] chief of the Gibichung clan:

Ravel’s "Pavane for a Dead Infanta", uses the cycle of fifths to evoke Baroque harmony to convey regret and nostalgia for a past era. The composer described the piece as "an evocation of a pavane that a little princess (infanta) might, in former times, have danced at the Spanish court.":[15]

Jazz and popular music

The enduring popularity of the circle of fifths as both a form-building device and as an expressive musical trope is evident in the number of "standard" popular songs composed during the twentieth century. It is also favored as a vehicle for improvisation by jazz musicians.

The song opens with a pattern of descending phrases – in essence, the hook of the song – presented with a soothing predictability, almost as if the future direction of the melody is dictated by the opening five notes. The harmonic progression, for its part, rarely departs from the circle of fifths.[16]

- Jerome Kern, "All the Things You Are"[17]

- Ray Noble, "Cherokee." Many jazz musicians have found this particularly challenging as the middle eight progresses so rapidly through the circle, "creating a series of II–V–I progressions that temporarily pass through several tonalities."[18]

- Kosmo, Prevert and Mercer, "Autumn Leaves"[19]

- The Beatles, "You Never Give Me Your Money" [20]

- Mike Oldfield, "Incantations"

- Carlos Santana, "Europa (Earth's Cry Heaven's Smile)"

- Gloria Gaynor, "I Will Survive"[21]

- Pet Shop Boys, "It's a Sin"

Related concepts

Diatonic circle of fifths

The diatonic circle of fifths is the circle of fifths encompassing only members of the diatonic scale. Therefore, it contains a diminished fifth, in C major between B and F. See structure implies multiplicity.

The circle progression is commonly a circle of fifths through the diatonic chords, including one diminished chord. A circle progression in C major with chords I–IV–viio–iii–vi–ii–V–I is shown below.

Chromatic circle

The circle of fifths is closely related to the chromatic circle, which also arranges the twelve equal-tempered pitch classes in a circular ordering. A key difference between the two circles is that the chromatic circle can be understood as a continuous space where every point on the circle corresponds to a conceivable pitch class, and every conceivable pitch class corresponds to a point on the circle. By contrast, the circle of fifths is fundamentally a discrete structure, and there is no obvious way to assign pitch classes to each of its points. In this sense, the two circles are mathematically quite different.

However, the twelve equal-tempered pitch classes can be represented by the cyclic group of order twelve, or equivalently, the residue classes modulo twelve, . The group has four generators, which can be identified with the ascending and descending semitones and the ascending and descending perfect fifths. The semitonal generator gives rise to the chromatic circle while the perfect fifth gives rise to the circle of fifths.

Relation with chromatic scale

The circle of fifths, or fourths, may be mapped from the chromatic scale by multiplication, and vice versa. To map between the circle of fifths and the chromatic scale (in integer notation) multiply by 7 (M7), and for the circle of fourths multiply by 5 (P5).

Here is a demonstration of this procedure. Start off with an ordered 12-tuple (tone row) of integers

- (0, 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11)

representing the notes of the chromatic scale: 0 = C, 2 = D, 4 = E, 5 = F, 7 = G, 9 = A, 11 = B, 1 = C♯, 3 = D♯, 6 = F♯, 8 = G♯, 10 = A♯. Now multiply the entire 12-tuple by 7:

- (0, 7, 14, 21, 28, 35, 42, 49, 56, 63, 70, 77)

and then apply a modulo 12 reduction to each of the numbers (subtract 12 from each number as many times as necessary until the number becomes smaller than 12):

- (0, 7, 2, 9, 4, 11, 6, 1, 8, 3, 10, 5)

which is equivalent to

- (C, G, D, A, E, B, F♯, C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, F)

which is the circle of fifths. Note that this is enharmonically equivalent to:

- (C, G, D, A, E, B, G♭, D♭, A♭, E♭, B♭, F).

Enharmonic equivalents and theoretical keys

The key signatures found on the bottom of the circle of fifths diagram, such as D♭ major, are often written one way in flats and in another way using sharps. These keys are easily interchanged using enharmonic equivalents. Enharmonic means that the notes sound the same, but are written differently. For example, the key signature of D♭ major, with five flats, contains the same sounding notes, enharmonically, as C♯ major (seven sharps).

After C♯ comes the key of G♯ (following the pattern of being a fifth higher, and, coincidentally, enharmonically equivalent to the key of A♭). The “eighth sharp” is placed on the F♯, to make it F![]()

![]()

![]()

There does not appear to be a standard on how to notate theoretical key signatures:

- The default behaviour of LilyPond (pictured above) writes all single sharps (flats) in the circle-of-fifths order, before proceeding to the double sharps. This is the format used in John Foulds' A World Requiem, Op. 60, which ends with the key signature of G♯ major (exactly as displayed above, pp. 153ff.) The sharps in the key signature of G♯ major here proceed C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F

- The single sharps or flats at the beginning are sometimes repeated as a courtesy, e.g. Max Reger's Supplement to the Theory of Modulation, which contains D♭ minor key signatures on pp. 42–45. These have a B♭ at the start and also a B

- Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B

See also

- Approach chord

- Sonata form

- Well temperament

- Circle of fifths text table

- Pitch constellation

Notes

- Michael Pilhofer and Holly Day (23 Feb 2009). "The Circle of Fifths: A Brief History", www.dummies.com.

- Nattiez 1990, p. 225.

- Goldman 1965, p. 68.

- Goldman 1965, chapter 3.

- Nattiez 1990, p. 226.

- Anon. "The Circle of Fifths: A Brief History". Dummies.com.

- https://www.classicfm.com/discover-music/music-theory/what-is-the-circle-of-fifths/. Missing or empty

|title=(help) - Anon. (2016). "The Circle of Fifths".

- Fraser, Peter A. (2001). "The Development of Musical Tuning Systems" (PDF): 9, 13. Retrieved 24 May 2020. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) (archive from 1 July 2013). - Jensen 1992, pp. 306–307.

- Whittall, A. (2002, p. 259) “Circle of Fifths”, article in Latham, E. (ed.) The Oxford Companion to Music. Oxford University Press.

- Taruskin, R. (2010, p. 184) The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries. Oxford University Press.

- Taruskin, R. (2010, p. 188) The Oxford History of Western Music: Music in the Seventeenth and Eighteenth centuries. Oxford University Press.

- Scruton, R. (2016, p. 121) The Ring of Truth: The Wisdom of Wagner’s Ring of the Nibelung. London, Allen Lane.

- Andres, Robert, "An introduction to the solo piano music of Debussy and Ravel", BBC Radio 3, accessed 17 November 2011

- Gioa, T. (2012, p.115) The Jazz Standards; a Guide to the repertoire. Oxford University Press.

- Gioa, T. (2012, p.16) The Jazz Standards; a Guide to the repertoire. Oxford University Press.

- Scott, Richard J. (2003, p. 123) Chord Progressions for Songwriters. Bloomington Indiana, Writers Club Press.

- Kostka, Stefan; Payne, Dorothy; Almén, Byron (2013). Tonal harmony with an introduction to twentieth-century music (7th ed.). New York: McGraw-Hill. pp. 46, 238. ISBN 978-0-07-131828-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "You Never Give Me Your Money" (1989, p1099-1100, bars 1-16) The Beatles Complete Scores. Hal Leonard.

- Fekaris, D. and Perren, F.J. (1978) I Will Survive. Polygram International Publishing.

- McCartin 1998, p. 364.

- https://www.hickeys.com/music/brass/brass_ensembles/brass_quintets/products/sku035994-ewald-victor-quintet-no-4-in-ab-op-8.php

References

- Goldman, Richard Franko (1965). Harmony in Western Music. New York: W. W. Norton.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jensen, Claudia R. (1992). "A Theoretical Work of Late Seventeenth-Century Muscovy: Nikolai Diletskii's "Grammatika" and the Earliest Circle of Fifths". Journal of the American Musicological Society. 45 (2 (Summer)): 305–331. JSTOR 831450.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McCartin, Brian J. (1998). "Prelude to Musical Geometry". The College Mathematics Journal. 29 (5 (November)): 354–370. JSTOR 2687250. Archived from the original on 2008-05-17. Retrieved 2008-07-29.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nattiez, Jean-Jacques (1990). Music and Discourse: Toward a Semiology of Music, translated by Carolyn Abbate. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-02714-5. (Originally published in French, as Musicologie générale et sémiologie. Paris: C. Bourgois, 1987. ISBN 2-267-00500-X).

Further reading

- D'Indy, Vincent (1903). Cours de composition musicale. Paris: A. Durand et fils.

- Lester, Joel. Between Modes and Keys: German Theory, 1592–1802. 1990.

- Miller, Michael. The Complete Idiot's Guide to Music Theory, 2nd ed. [Indianapolis, IN]: Alpha, 2005. ISBN 1-59257-437-8.

- Purwins, Hendrik (2005)."Profiles of Pitch Classes: Circularity of Relative Pitch and Key—Experiments, Models, Computational Music Analysis, and Perspectives". Ph.D. Thesis. Berlin: Technische Universität Berlin.

- Purwins, Hendrik, Benjamin Blankertz, and Klaus Obermayer (2007). "Toroidal Models in Tonal Theory and Pitch-Class Analysis". in: Computing in Musicology 15 ("Tonal Theory for the Digital Age"): 73–98.