Theoretical key

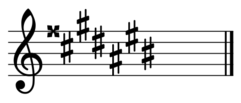

In music theory, a theoretical key or impossible key is a key whose key signature has at least one double-flat (![]()

![]()

Double-flats and double-sharps are often used as accidentals, but placing them in the key signature (in music that uses equal temperament) makes the music generally impractical to read.

Enharmonic equivalence

| G♯ major: | G♯ | A♯ | B♯ | C♯ | D♯ | E♯ | F |

| A♭ major: | A♭ | B♭ | C | D♭ | E♭ | F | G |

For example, the key of G-sharp major is a key of this type, because its corresponding key signature has an F![]()

Even when enharmonic equivalence is not resorted to, it is more common to use either no key signature or one with single-sharps and to provide accidentals as needed for the F![]()

Modulation

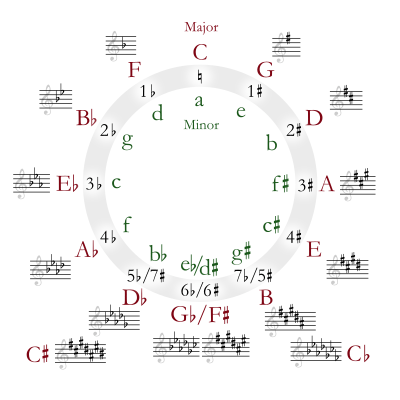

While a piece of Western music generally has a home key, a passage within it may modulate to another key, which is usually closely related to the home key (in the Baroque and early Classical eras), that is, close to the original around the circle of fifths. When the key is near the top of the circle (a key signature of zero or few accidentals), the notation of both keys is straightforward. But if the home key is near the bottom of the circle (a key signature of many accidentals), and particularly if the new key is on the opposite side (in the late Classical and Romantic eras), it becomes necessary to consider enharmonic equivalence (if double accidentals are to be avoided).

In each of the bottom three places on the circle of fifths the two enharmonic equivalents can be notated entirely with single accidentals and so do not classify as 'theoretical keys':

| Major (minor) | Key signature | Major (minor) | Key signature | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B (g♯) | 5 sharps | C♭ (a♭) | 7 flats | |

| F♯ (d♯) | 6 sharps | G♭ (e♭) | 6 flats | |

| C♯ (a♯) | 7 sharps | D♭ (b♭) | 5 flats |

The need to consider theoretical keys

However, when a parallel key ascends the opposite side of the circle from its home key, then theory suggests that double-sharps and double-flats would have to be incorporated into the notated key signature. The following keys (six of which are the parallel major/minor keys of those above) would require up to seven double-sharps or double-flats:

| Key | Key signature | Relative key |

|---|---|---|

| D♭ minor (C♯ minor) | 8 flats | F♭ major (E major) |

| G♭ minor (F♯ minor) | 9 flats | B |

| C♭ minor (B minor) | 10 flats | E |

| F♭ minor (E minor) | 11 flats | A |

| B | 12 flats | D |

| E | 13 flats | G |

| A | 14 flats | C |

| G♯ major (A♭ major) | 8 sharps | E♯ minor (F minor) |

| D♯ major (E♭ major) | 9 sharps | B♯ minor (C minor) |

| A♯ major (B♭ major) | 10 sharps | F |

| E♯ major (F major) | 11 sharps | C |

| B♯ major (C major) | 12 sharps | G |

| F | 13 sharps | D |

| C | 14 sharps | A |

For example, pieces in the major mode commonly modulate up a fifth to the dominant; for a key with sharps in the signature this leads to a key whose key signature has an additional sharp. A piece in C-sharp that performs this modulation would lead to the theoretical key of G-sharp major, requiring eight sharps, meaning an F![]()

Notation

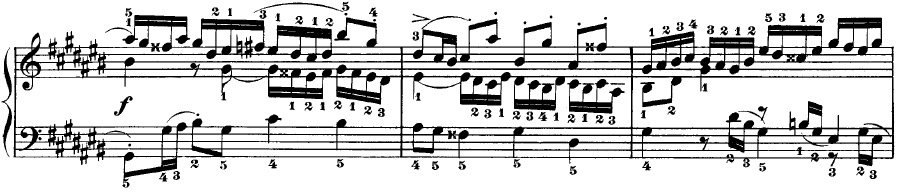

Such passages may instead be notated with the use of double-sharp or double-flat accidentals, as in this example from Johann Sebastian Bach's Well-Tempered Clavier, in G-sharp major (the overall key is C-sharp major):

In very few cases, theoretical keys are in fact used directly, putting the necessary double-accidentals in the key signature. The final pages of John Foulds' A World Requiem are written in G♯ major (with F![]()

![]()

There does not appear to be a standard on how to notate theoretical key signatures:

- The default behaviour of LilyPond (pictured above) writes all single sharps (flats) in the circle-of-fifths order, before proceeding to the double sharps. This is the format used in John Foulds' A World Requiem, Op. 60, which ends with the key signature of G♯ major exactly as displayed above.[2] The sharps in the key signature of G♯ major here proceed C♯, G♯, D♯, A♯, E♯, B♯, F

- The single sharps or flats at the beginning are sometimes repeated as a courtesy, e.g. Max Reger's Supplement to the Theory of Modulation, which contains D♭ minor key signatures on pp. 42–45.[3] These have a B♭ at the start and also a B

- Sometimes the double signs are written at the beginning of the key signature, followed by the single signs. For example, the F♭ key signature is notated as B

Tunings other than twelve-tone equal-temperament

In a different tuning system (such as 19 tone equal temperament) there may be keys that do require a double-sharp or double-flat in the key signature, and no longer have conventional equivalents. For example, in 19 tone equal temperament, the key of B![]()

See also

- Closely related key

- Diatonic function

References

- "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8". Ensemble Publications. Retrieved 14 April 2020.

- John Foulds: A World Requiem, pp. 153ff.: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

- Max Reger (1904). Supplement to the Theory of Modulation. Translated by John Bernhoff. Leipzig: C. F. Kahnt Nachfolger. pp. 42–45.

- "Ewald, Victor: Quintet No 4 in A♭, op 8", Hickey's Music Center