Resolution (music)

Resolution in western tonal music theory is the move of a note or chord from dissonance (an unstable sound) to a consonance (a more final or stable sounding one).

Dissonance, resolution, and suspense can be used to create musical interest. Where a melody or chordal pattern is expected to resolve to a certain note or chord, a different but similarly suitable note can be resolved to instead, creating an interesting and unexpected sound. For example, the deceptive cadence.

Basis

A dissonance has its resolution when it moves to a consonance. When a resolution is delayed or is accomplished in surprising ways—when the composer plays with our sense of expectation—a feeling of drama or suspense is created.

Resolution has a strong basis in tonal music, since atonal music generally contains a more constant level of dissonance and lacks a tonal center to which to resolve.

The concept of "resolution", and the degree to which resolution is "expected", is contextual as to culture and historical period. In a classical piece of the Baroque period, for example, an added sixth chord (made up of the notes C, E, G and A, for example) has a very strong need to resolve, while in a more modern work, that need is less strong - in the context of a pop or jazz piece, such a chord could comfortably end a piece and have no particular need to resolve.

Example

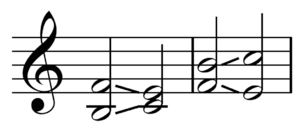

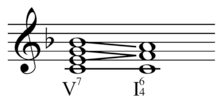

An example of a single dissonant note which requires resolution would be, for instance, an F during a C major chord, C–E–G, which creates a dissonance with both E and G and may resolve to either, though more usually to E (the closer pitch). This is an example of a suspended chord. In reference to chords and progressions for example, a phrase ending with the following cadence IV–V, a half cadence, does not have a high degree of resolution. However, if this cadence were changed to (IV–)V–I, an authentic cadence, it would resolve much more strongly by ending on the tonic I chord.

Sources

- Benjamin, Horvit, and Nelson (2008). Techniques and Materials of Music, p.46. ISBN 0-495-50054-2.

- Kamien, Roger (2008). Music: An Appreciation, 6th Brief Edition, p.41. ISBN 978-0-07-340134-8.

- Forte, Allen (1979). Tonal Harmony in Concept & Practice, p. 145. Third edition. ISBN 0-03-020756-8.