Maroons

Maroons are descendants of Africans in the Americas who formed settlements away from slavery. They often mixed with indigenous peoples, eventually evolving into separate creole cultures[1] such as the Garifuna and the Mascogos.

| |

| Regions with significant populations | |

|---|---|

| North and South America | |

| Languages | |

| Creole languages | |

| Religion | |

| African diasporic religions | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Maroon peoples Black Seminoles, Bushinengue, Jamaican Maroons, Kalungas, Palenqueros, Quilombola Great Dismal Swamp maroons |

Etymology

Maroon, which can have a more general sense of being abandoned without resources, entered English around the 1590s, from the French adjective marron,[2] meaning 'feral' or 'fugitive'.

The American Spanish word cimarrón is often given as the source of the English word maroon, used to describe the runaway slave communities in Florida, in the Great Dismal Swamp on the border of Virginia and North Carolina, on colonial islands of the Caribbean, and in other parts of the New World. Lyle Campbell says the Spanish word cimarrón means 'wild, unruly' or 'runaway slave'.[3] The linguist Leo Spitzer, writing in the journal Language, says: "If there is a connection between Eng. maroon, Fr. marron, and Sp. cimarrón, Spain (or Spanish America) probably gave the word directly to England (or English America)."[4] The Cuban philologist José Juan Arrom has traced the origins of the word maroon further than the Spanish cimarrón, used first in Hispaniola to refer to feral cattle, then to enslaved Indians who escaped to the hills, and by the early 1530s to enslaved Africans who did the same. He proposes that the American Spanish word derives ultimately from the Arawakan root word simarabo, construed as 'fugitive', in the Arawakan language spoken by the Taíno people native to the island.[5][6][7][8][9]

History

In the New World, as early as 1512, enslaved Africans escaped from Spanish captors and either joined indigenous peoples or eked out a living on their own.[10] Sir Francis Drake enlisted several cimarrones during his raids on the Spanish.[11] As early as 1655, escaped Africans had formed their communities in inland Jamaica, and by the 18th century, Nanny Town and other villages began to fight for independent recognition.[12]

When runaway Blacks and Amerindians banded together and subsisted independently they were called maroons. On the Caribbean islands, they formed bands and on some islands, armed camps. Maroon communities faced great odds against their surviving attacks by hostile colonists,[13] obtaining food for subsistence living,[14] as well as reproducing and increasing their numbers. As the planters took over more land for crops, the maroons began to lose ground on the small islands. Only on some of the larger islands were organized maroon communities able to thrive by growing crops and hunting. Here they grew in number as more Blacks escaped from plantations and joined their bands. Seeking to separate themselves from Whites, the maroons gained in power and amid increasing hostilities, they raided and pillaged plantations and harassed planters until the planters began to fear a massive revolt of the enslaved Blacks.[15]

The early maroon communities were usually displaced. By 1700, maroons had disappeared from the smaller islands. Survival was always difficult, as the maroons had to fight off attackers as well as grow food.[15] One of the most influential maroons was François Mackandal, a houngan or voodoo priest, who led a six-year rebellion against the white plantation owners in Haiti that preceded the Haitian Revolution.[16]

In Cuba, there were maroon communities in the mountains, where African refugees who escaped the brutality of slavery and joined refugee Taínos.[17] Before roads were built into the mountains of Puerto Rico, heavy brush kept many escaped maroons hidden in the southwestern hills where many also intermarried with the natives. Escaped Blacks sought refuge away from the coastal plantations of Ponce.[18] Remnants of these communities remain to this day (2006) for example in Viñales, Cuba,[19] and Adjuntas, Puerto Rico.

Maroon communities emerged in many places in the Caribbean (St Vincent and Dominica, for example), but none were seen as such a great threat to the British as the Jamaican Maroons.[20] A British governor signed a treaty in 1739 and 1740 promising them 2,500 acres (1,012 ha) in two locations, to bring an end to the warfare between the communities. In exchange, they were to agree to capture other escaped Blacks. They were paid a bounty of two dollars for each African returned.[21]

Beginning in the late 17th century, Jamaican Maroons fought British colonists to a draw and eventually signed treaties in the mid-18th century, that effectively freed them a century before the Slavery Abolition Act 1833, which came into effect in 1838. To this day, the Jamaican Maroons are to a significant extent autonomous and separate from Jamaican society. The physical isolation used to their advantage by their ancestors has today led to their communities remaining among the most inaccessible on the island. In their largest town, Accompong, in the parish of St Elizabeth, the Leeward Maroons still possess a vibrant community of about 600. Tours of the village are offered to foreigners and a large festival is put on every January 6 to commemorate the signing of the peace treaty with the British after the First Maroon War.[12][22]

In the plantation colony of Suriname, which England ceded to the Netherlands in the Treaty of Breda (1667), escaped Blacks revolted and started to build their villages from the end of the 17th century. As most of the plantations existed in the eastern part of the country, near the Commewijne River and Marowijne River, the Marronage (i.e., running away) took place along the river borders and sometimes across the borders of French Guiana. By 1740, the maroons had formed clans and felt strong enough to challenge the Dutch colonists, forcing them to sign peace treaties. On October 10, 1760, the Ndyuka signed such a treaty, drafted by Adyáko Benti Basiton of Boston, a former enslaved African from Jamaica who had learned to read and write and knew about the Jamaican treaty. The treaty is still important, as it defines the territorial rights of the Maroons in the gold-rich inlands of Suriname.[23]

Culture

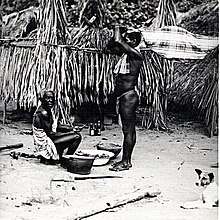

Enslaved people escaped frequently within the first generation of their arrival from Africa and often preserved their African languages and much of their culture and religion. African traditions included such things as the use of medicinal herbs together with special drums and dances when the herbs are administered to a sick person. Other African healing traditions and rites have survived through the centuries.

The jungles around the Caribbean Sea offered food, shelter, and isolation for the escaped enslaved people. Maroons sustained themselves by growing vegetables and hunting. Their survival depended upon military abilities and culture of these communities, using guerrilla tactics and heavily fortified dwellings involving traps and diversions. Some defined leaving the community as desertion and therefore punishable by death.[24] They also originally raided plantations. During these attacks, the maroons would burn crops, steal livestock and tools, kill slavemasters, and invite other enslaved people to join their communities. Individual groups of maroons often allied themselves with the local indigenous tribes and occasionally assimilated into these populations. Maroons played an important role in the histories of Brazil, Suriname, Puerto Rico, Haiti, Dominican Republic, Cuba, and Jamaica.

There is much variety among maroon cultural groups because of differences in history, geography, African nationality, and the culture of indigenous people throughout the Western Hemisphere.

Maroon settlements often possessed a clannish, outsider identity. They sometimes developed Creole languages by mixing European tongues with their original African languages. One such maroon creole language, in Suriname, is Saramaccan. At other times, the maroons would adopt variations of a local European language (creolization) as a common tongue, for members of the community frequently spoke a variety of mother tongues.[24]

The maroons created their own independent communities, which in some cases have survived for centuries, and until recently remained separate from mainstream society. In the 19th and 20th centuries, maroon communities began to disappear as forests were razed, although some countries, such as Guyana and Suriname, still have large maroon populations living in the forests. Recently, many of them moved to cities and towns as the process of urbanization accelerates.

Types of maroons

A typical maroon community in the early stage usually consists of three types of people.[24]

- Most of them were enslaved people who ran away right after they got off the ships. They refused to surrender their freedom and often tried to find ways to go back to Africa.

- The second group were enslaved people who had been working on plantations for a while. Those enslaved people were usually somewhat adjusted to the slave system but had been abused by the plantation owners – often with excessive brutality. Others ran away when they were being sold suddenly to a new owner.

- The last group of maroons were usually skilled enslaved people with particularly strong opposition to the slave system.

Relationship with colonial governments

Maroonage was a constant threat to New World plantation societies.[25] Punishments for recaptured maroons were severe, like removing the Achilles tendon, amputating a leg, castration, and being roasted to death.[25]

Maroon communities had to be inaccessible and were located in inhospitable environments to be sustainable.[25] For example, maroon communities were established in remote swamps in the southern United States; in deep canyons with sinkholes but little water or fertile soil in Jamaica; and in deep jungles of the Guianas.[25]

Maroon communities turned the severity of their environments to their advantage to hide and defend their communities.[25] Disguised pathways, false trails, booby traps, underwater paths, quagmires and quicksand, and natural features were all used to conceal maroon villages.[25]

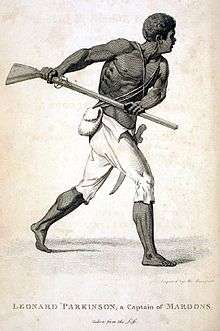

Maroon men utilized exemplary guerrilla warfare skills to fight their European enemies. Nanny, the famous Jamaican maroon, developed guerrilla warfare tactics that are still used today by many militaries around the world.[25] European troops used strict and established strategies while maroon men attacked and retracted quickly, used ambush tactics, and fought when and where they wanted to.[25]

Even though colonial governments were in a perpetual state of hatred toward the maroon communities, individuals in the colonial system traded goods and services with them.[25] Maroons also traded with isolated white settlers and Native American communities.[25] Maroon communities played interest groups off of one another.[25] At the same time, maroon communities were also used as pawns when colonial powers clashed.[25]

Absolute secrecy and loyalty of members were crucial to the survival of maroon communities.[25] To ensure this loyalty, maroon communities used severe methods to protect against desertion and spies.[25] New members were brought to communities by way of detours so they could not find their way back and served probationary periods, often as enslaved people.[25] Crimes such as desertion and adultery were punishable by death.[25]

Geographical distribution

Caribbean islands

Cuba

In Cuba, escaped enslaved people had joined refugee Taínos in the mountains to form maroon communities.[17] There are 28 identified archaeological sites in the Viñales Valley related to runaway African slaves or maroons of the early 19th century; the material evidence of their presence is found in caves of the region, where groups settled for various lengths of time. Oral tradition tells that maroons took refuge on the slopes of the mogotes and in the caves; the Viñales Municipal Museum has archaeological exhibits that depict the life of runaway slaves, as deduced through archeological research. Cultural traditions reenacted during the Semana de la Cultura (Week of Culture) celebrate the town's founding in 1607.[26][27]

Dominica, St Lucia, and St Vincent

Similar maroon communities developed on islands across the Caribbean, such as those of the Garifuna people. Many of the Garifuna were deported to the mainland, where some eventually settled along the Mosquito Coast or in Belize. From their original landing place in Roatan Island, the maroons moved to Trujillo. Gradually groups migrated south into the Miskito Kingdom and north into Belize.[28]

Runaway slaves and fugitive French republican soldiers formed the so-called Armée Française dans les bois (French army in the woods), which comprised about 6,000 men who fought a guerilla war against the British army occupying Santa Lucia.[29] Led by the French Commissioner, Gaspard Goyrand,[30] they succeeded in taking back most of the island from the British, but on 26 May 1796, their forces defending the fort at Morne Fortune, about 2,000 men, surrendered to a British division under the command of General John Moore.[31][32] After the capitulation, over 2,500 prisoners of war, mostly black or mixed-race, as well as ninety-nine women and children, were transported from St Lucia to Portchester Castle.[33][34]

Dominican Republic

American marronage began in Spain's colony on the island of Hispaniola. Governor Nicolás de Ovando was already complaining of escaped slaves and their interactions with the Taino Indians by 1503. Maroons joined the natives in their wars against the Spanish and hid with the rebel chieftain Enriquillo in the Bahoruco Mountains. When Archdeacon Alonso de Castro toured Hispaniola in 1542, he estimated the maroon population at 2,000–3,000 persons.[35][36]

Haiti

The French encountered many forms of slave resistance during the 17th and 18th centuries. Enslaved Africans who fled to remote mountainous areas were called marron (French) or mawon (Haitian Creole), meaning 'escaped slave'. The maroons formed close-knit communities that practised small-scale agriculture and hunting. They were known to return to plantations to free family members and friends. On a few occasions, they also joined the Taíno settlements, who had escaped the Spanish in the 17th century. Other slave resistance efforts against the French plantation system were more direct. The maroon leader Mackandal led a movement to poison the drinking water of the plantation owners in the 1750s.[37] Boukman declared war on the French plantation owners in 1791, setting off the Haitian Revolution. A statue called the Le Nègre Marron or the Nèg Mawon is an iconic bronze bust that was erected in the heart of Port-au-Prince to commemorate the role of maroons in Haitian independence.[38]

Jamaica

Escaped enslaved people during the Spanish occupation of the island of Jamaica fled to the interior and joined the Taíno living there, forming refugee communities. Later, many of them gained freedom during the confusion surrounding the 1655 English Invasion of Jamaica.[39] Refugee enslaved people continued to join them through the decades until the abolition of slavery in 1838. During the late 17th and 18th centuries, the British tried to capture the maroons because they occasionally raided plantations, and made expansion into the interior more difficult. An increase in armed confrontations over decades led to the First Maroon War in the 1730s, but the British were unable to defeat the maroons. They finally settled with the groups by treaty in 1739 and 1740, allowing them to have autonomy in their communities in exchange for agreeing to be called to military service with the colonists if needed. Certain maroon factions became so formidable that they made treaties with local colonial authorities,[40] sometimes negotiating their independence in exchange for helping to hunt down other enslaved people who escaped.[41]

Due to tensions and repeated conflicts with maroons from Trelawny Town, the Second Maroon War erupted in 1795. After the governor tricked the Trelawny Maroons into surrendering, the colonial government deported approximately 600 captive maroons to Nova Scotia. Due to their difficulties and those of Black Loyalists settled at Nova Scotia and England after the American Revolution, Great Britain established a colony in West Africa, Sierra Leone. It offered ethnic Africans a chance to set up their community there, beginning in 1792. Around 1800, several Jamaican maroons were transported to Freetown, the first settlement of Sierra Leone.

The only Leeward Maroon settlement that retained formal autonomy in Jamaica after the Second Maroon War was Accompong, in Saint Elizabeth Parish, whose people had abided by their 1739 treaty with the British. A Windward Maroon community is also located at Charles Town, on Buff Bay River in Portland Parish. Another is at Moore Town (formerly Nanny Town), also in the parish of Portland. In 2005, the music of the Moore Town Maroons was declared by UNESCO as a 'Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.'[42] A fourth community is at Scott's Hall, also in the parish of Portland.[43] Accompong's autonomy was ratified by the government of Jamaica when the island gained independence in 1962.

The government has tried to encourage the survival of the other maroon settlements. The Jamaican government and the maroon communities organized the Annual International Maroon Conference, initially to be held at rotating communities around the island, but the conference has been held at Charles Town since 2009.[44] Maroons from other Caribbean, Central, and South America nations are invited. In 2016, Accompong's colonel and a delegation traveled to the Kingdom of Ashanti in Ghana to renew ties with the Akan and Asante people of their ancestors.[45]

Puerto Rico

In Puerto Rico, Taíno families from neighboring Utuado moved into the southwestern mountain ranges, along with escaped African enslaved people who intermarried with them. The DNA analysis of contemporary persons from this area shows maternal ancestry from the Mandinka, Wolof, and Fulani peoples through the mtDNA African haplotype associated with them, L1b, which is present here. This was carried by African enslaved people who escaped from plantations around Ponce and formed communities with the Arawak (Taíno and Kalinago) in the mountains.[46] Arawak lineages (Taíno people represented within haplogroups A and Kalinago people represented within haplogroups C) can also be found in this area.

Central America

Belize, Guatemala, Honduras, and Nicaragua

Several different maroon societies developed around the Gulf of Honduras. Some were found in the interior of modern-day Honduras, along the trade routes by which silver mined on the Pacific side of the isthmus was carried by enslaved people down to coastal towns such as Trujillo or Puerto Caballos to be shipped to Europe. When enslaved people escaped, they went to the mountains for safety. In 1648, the English bishop of Guatemala, Thomas Gage, reported active bands of maroons numbering in the hundreds along these routes.

The Miskito Sambu were a maroon group who formed from enslaved people who revolted on a Portuguese ship around 1640, wrecking the vessel on the coast of Honduras-Nicaragua and escaping into the interior. They intermarried with the indigenous people over the next half-century. They eventually rose to leadership of the Mosquito Coast and led extensive slave raids against Spanish-held territories in the first half of the 18th century.

The Garifuna are descendants of maroon communities that developed on the island of Saint Vincent. They were deported to the coast of Honduras in 1797.[28].

Panama

Bayano, a Mandinka man who had been enslaved and taken to Panama in 1552, led a rebellion that year against the Spanish in Panama. He and his followers escaped to found villages in the lowlands. Later these people, known as the Cimarrón, assisted Sir Francis Drake in fighting against the Spanish.

North America

Mexico

Gaspar Yanga was an African leader of a Maroon colony in the Veracruz highlands in what is now Mexico. In 1609, after having been a fugitive for 38 years, Yanga negotiated with the Spanish colonists to establish a self-ruled maroon settlement called San Lorenzo de los Negros, (later renamed Yanga).[47]

Nova Scotia

In the 1790s, about 600 Jamaican Maroons were deported to British settlements in Nova Scotia, where British slaves who had escaped from the United States were also resettled. Being unhappy with conditions, in 1800, a majority emigrated to what is now Sierra Leone in Africa.

Florida

Maroons who escaped from British colonies and allied with Seminole Indians were one of the largest and most successful maroon communities in what is now Florida due to more rights and freedoms granted by the Spanish Empire. Some intermarried and were culturally Seminole; others maintained a more African culture. Descendants of those who were removed with the Seminole to Indian Territory in the 1830s are recognized as Black Seminoles. Many were formerly part of the Seminole Nation of Oklahoma, but have been excluded since the late 20th century by new membership rules that require proving Native American descent from historic documents.

Louisiana

Until the mid-1760s, maroon colonies lined the shores of Lake Borgne, just downriver of New Orleans, Louisiana. These fugitive enslaved people controlled many of the canals and back-country passages from Lake Pontchartrain to the Gulf, including the Rigolets. These colonies were finally eradicated by militia from Spanish-controlled New Orleans led by Francisco Bouligny. Free people of color aided in the capture of these fugitives.[48][49]

North Carolina and Virginia

The Great Dismal Swamp maroons inhabited the marshlands of the Great Dismal Swamp in Virginia and North Carolina. Although conditions were harsh, research suggests that thousands lived there between about 1700 and the 1860s.

South America

Brazil

One of the best-known quilombos (maroon settlements) in Brazil was Palmares (the Palm Nation), which was founded in the early 17th century. At its height, it had a population of over 30,000 free people and was ruled by king Zumbi. Palmares maintained its independent existence for almost a hundred years until it was conquered by the Portuguese in 1694.

Colombia

Escaped enslaved people established independent communities along the remote Pacific coast, outside of the reach of the colonial administration. In Colombia, the Caribbean coast still sees maroon communities like San Basilio de Palenque, where the creole Palenquero language is spoken.

Ecuador

In addition to escaped enslaved people, survivors from shipwrecks formed independent communities along rivers of the northern coast and mingled with indigenous communities in areas beyond the reach of the colonial administration. Separate communities can be distinguished from the cantones Cojimies y Tababuela, Esmeraldas, Limones.

French Guiana and Suriname

In French Guiana and Suriname (where maroons account for about 15% of the population),[50] escaped enslaved people, or Bushinengues, fled to the interior and joined with indigenous peoples and created several independent tribes, among them the Saramaka, the Paramaka, the Ndyuka (Aukan), the Kwinti, the Aluku (Boni), and the Matawai. The Ndyuka were the first to sign a peace treaty offering them territorial autonomy in 1760.[51] In the 1770s, the Aluku also desired a peace treaty, however the Society of Suriname, started a war against them,[52] resulting in an flight into French Guiana.[53] The other tribes signed peace treaties with the Surinamese government, the Kwinti being the last in 1887.[54] On 25 May 1891 the Aluku officially became French citizens.[55]

By the 1980s the Bushinengues in Suriname had begun to fight for their land rights.[56] Between 1986 and 1992,[57] the Surinamese Interior War was waged by the Jungle Commando, a guerrilla group fighting for the rights of the maroon minority, against the military dictatorship of Dési Bouterse.[58] In 2005, following a ruling by the Inter-American Court of Human Rights, the Suriname government agreed to compensate survivors of the 1986 Moiwana village massacre, in which soldiers had slaughtered 39 unarmed Ndyuka people, mainly women and children.[50] On 13 June 2020, Ronnie Brunswijk was elected Vice President of Suriname by acclamation in an uncontested election.[59] He was inaugurated on 16 July[60] as the first Maroon in Suriname to serve as Vice President.[61]

Indian Ocean islands

Mauritius

Maroons in Mauritius included Diamamouve.

See also

- Slave catcher

- Slave rebellion

- Afro-Latin American: Latin Americans of significant or mainly African ancestry.

- Black Seminoles: Indians associated with the Seminole people in Florida and Oklahoma.

- Bushinengues: in French Guiana, meaning people of the forest, descendants of slaves who escaped enslavement and established independent communities in the forest.

- Gaspar Yanga: an African known for being the leader of a maroon colony of slaves in New Spain.

- Saramaka: one of six Maroon peoples in the Republic of Suriname and one of the Maroon peoples in French Guiana.

- Quilombo a 1985 film about Quilombo dos Palmares, a fugitive community of escaped slaves and others, in colonial Brazil.

References

- Diouf, Sylviane A. (Sylviane Anna) (2016). Slavery's exiles : the story of the American Maroons. New York: NYU. pp. 81, 171–177, 215, 309. ISBN 9780814724491. OCLC 864551110.

- "Maroon definition and meaning". www.collinsdictionary.com. Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Lyle Campbell (2000). American Indian Languages: The Historical Linguistics of Native America. Oxford University Press. p. 400. ISBN 978-0-19-514050-7.

- Leo Spitzer (1938). "Spanish cimarrón". Language. Linguistic Society of America". 14 (2): 145–147. doi:10.2307/408879. JSTOR 408879.

The Shorter Oxford Dictionary explains maroon 'fugitive negro slave' as from 'Fr. marron, said to be a corruption of Sp. cimarrón, wild, untamed'. But Eng.maroon is attested earlier (1666) than Fr. marron 'fugitive slave' (1701, in Furetiere). If there is a connection between Eng. maroon, Fr. marron, and Sp. cimarrón, Spain (or Spanish America) probably gave the word directly to England (or English America).

- José Juan Arrom (1983). "Cimarrón: apuntes sobre sus primeras documentaciones y su probable origen". Revista Española de Antropología Americana. Madrid: Universidad Complutense. XII: 10.

Y si prestamos atención al testimonio de Oviedo cuando, después de haber vivido en la Española por muchos años, asevera que cimarrón «quiere decir, en la lengua desta isla, fugitivos», quedaría demostrado que nos hallamos, en efecto, ante un temprano préstamo de la lengua taina.» English: And if we pay attention to the testimony of Oviedo when, after having lived in Hispaniola for many years, he asserts that cimarrón "means, in the language of this island, fugitives", it would be demonstrated that we are, in fact, before an early loan of the Taíno language.

- José Juan Arrom; Manuel Antonio García Arévalo (1986). Cimarrón. Ediciones Fundación García-Arévalo. p. 30.

En resumen, los informes que aquí aporto confirman que cimarrón es un indigenismo de origen antillano, que se usaba ya en el primer tercio de siglo xvi, y que ha venido a resultar otro de los numerosos antillanismos que la conquista extendió por todo el ámbito del continente e hizo refluir sobre la propia metrópoli. English: In short, the reports that I am contributing here confirm that cimarrón is an Indian word of Antillean origin, which was already used in the first third of the sixteenth century, and which has come to be another of the many antillanisms that the conquest extended throughout the breadth of the continent and made to reflect on the metropolis itself.

- Richard Price (3 September 1996). Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas. JHU Press. pp. xi–xii. ISBN 978-0-8018-5496-5.

- Wright, 106,

- José Juan Arrom (1 January 2000). Estudios de lexicología antillana. Editorial de la Universidad de Puerto Rico. p. 128. ISBN 978-0-8477-0374-6.

- "Sir Francis Drake Revived, in Voyages and Travels: Ancient and Modern, The Harvard Classics. 1909–14, para. 21.

- "Sir Francis Drake Revived", in Voyages and Travels, para. 101.

- Campbell, Mavis Christine (1988), The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655–1796: A History of Resistance, Collaboration & Betrayal, Granby, MA: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-148-1.

- American Vistas. 1971. p. 23.

- Don C. Ohadike (1 January 2002). Pan-African Culture of Resistance: A History of Liberation Struggles in Africa and the Diaspora. Global Publications, Binghamton University. p. 22. ISBN 978-1-58684-175-1.

- Rogozinski, Jan (1999). A Brief History of the Caribbean (revised ed.). New York: Facts on File, Inc. pp. 155–68. ISBN 0-8160-3811-2.

- "The History of Haiti and the Haitian Revolution". The City of Miami. Archived from the original on 2007-08-26. Retrieved 2007-08-16.

- Aimes, Hubert H. S. (1967), A History of Slavery in Cuba, 1511 to 1868, New York: Octagon Books.

- Franklin W. Knight, Review of Benjamin Nistal-Moret, Esclavos prófugos y cimarrones: Puerto Rico, 1770–1870, in the Hispanic American Historical Review, Vol. 66, No. 2 (May 1986), pp. 381–82.

- "El Templo de los Cimarrónes" Guerrillero: Pinar del Río Archived 2008-05-08 at the Wayback Machine in Spanish

- Edwards, Bryan (1801), Historical Survey of the Island of Saint Domingo, London: J. Stockdale.

- Taylor, Alan (2001), American Colonies: The Settling of North America, New York: Penguin Books.

- Edwards, Bryan (1796), "Observations on the disposition, character, manners, and habits of life, of the Maroons of the island of Jamaica; and a detail of the origin, progress, and termination of the late war between those people and the white inhabitants." in Edwards, Bryan (1801), Historical Survey of the Island of Saint Domingo, London: J. Stockdale, pp. 303–360.

- Alex van Stipriaan, Surinaams contrast (1995); Hans Buddingh', Geschiedenis van Suriname (1995/1999); Alex van Stipriaan/Thomas Polimé, Kunst van overleven (KIT, 2009).

- Price, Richard (1973). Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas. Garden City, New York: Anchor Press. p. 25. ISBN 0385065086. OCLC 805137.

- Price, Richard (1979). Maroon Societies: Rebel Slave Communities in the Americas. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 1–30. ISBN 0-8018-2247-5.

- "Places of Memory of the Slave Route in the Latin Caribbean en el Caribe Latino". www.lacult.unesco.org. 2019. Archived from the original on 4 September 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Loraine Morales Pino. "Viñales celebra semana de la Cultura". Periódico Guerrillero (in Spanish). Guerrillero. Archived from the original on 2 December 2019. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Carel Henning Roessingh (1 January 2001). The Belizean Garifuna: Organization of Identity in an Ethnic Community in Central America. Rozenberg. p. 71. ISBN 978-90-5170-574-4.

- Aline Helg; Translated by Lara Vergnaud (7 February 2019). "The Shock Waves of the Haitian Revolution". Slave No More: Self-Liberation before Abolitionism in the Americas [Plus jamais esclaves! De l’ insoumission à la révolte, le grand récit d’ une émancipation (1492–1838)]. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. p. 170. ISBN 978-1-4696-4964-1.

- Martin Howard (30 September 2015). Death Before Glory: The British Soldier in the West Indies in the French Revolutionary and Napoleonic Wars 1793-1815. Pen and Sword. p. 21. ISBN 978-1-4738-7152-6.

- Henry Hegart Breen (1844). St. Lucia: Historical, Statistical, and Descriptive. Longman, Brown, Green, and Longmans. p. 96.

- James Henry Stark (1893). Stark's History and Guide to Barbados and the Caribbee Islands: Containing a Description of Everything on Or about These Islands of which the Visitor Or Resident May Desire Information ... Fully Illustrated with Maps, Engravings and Photo-prints. Photo-Electrotype Company. p. 55.

- "Black prisoners at Portchester Castle". English Heritage. Archived from the original on 24 July 2019.

- Mark Brown (18 July 2017). "Hidden story of 2,000 African-Caribbean PoWs in a medieval castle". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 20 May 2019. Retrieved 20 December 2019.

- Jane Landers (2002). "The Central African Presence in Spanish Maroon Communities". In Linda M. Heywood (ed.). Central Africans and Cultural Transformations in the American Diaspora. Cambridge University Press. p. 234. ISBN 978-0-521-00278-3.

- Jane Landers (1 October 2008). "Transforming Bondsmen into Vassals". In Christopher Leslie Brown Philip D. Morgan (ed.). Arming Slaves: From Classical Times to the Modern Age. Yale University Press. p. 139, note 17. ISBN 978-0-300-13485-8.

- Corbett, Bob. The Haitian Revolution of 1791-1803, An Historical Essay in Four Parts. Archived from the original on 14 September 2019.

- Press (Obituaries, PASSINGS), ed. (27 April 2002). "Albert Mangones, 85; His Bronze Sculpture Became Haitian Symbol". LA Times. Retrieved 9 March 2016.

- Nicholas J. Saunders (2005). The Peoples of the Caribbean: An Encyclopedia of Archaeology and Traditional Culture. ABC-CLIO. p. 145. ISBN 978-1-57607-701-6.

- Eugene D. Genovese (1 January 1992). From Rebellion to Revolution: Afro-American Slave Revolts in the Making of the Modern World. LSU Press. p. 65. ISBN 978-0-8071-4813-6.

Some maroon communities became powerful enough to force the European powers into formal peace treaties designed to pacify the interior while recognizing the freedom and autonomy of the rebels. Jamaica and Surinam provided the most famous of these cases, which had counterparts in Mexico...

- Cécile Accilien; Jessica Adams; Elmide Méléance (2006). Revolutionary Freedoms: A History of Survival, Strength and Imagination in Haiti. Educa Vision Inc. p. 81. ISBN 978-1-58432-293-1.

- Tanya Batson-Savage (13 June 2004). "Jamaica Gleaner Online". old.jamaica-gleaner.com. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Garfield L. Angus (17 July 2015). "Scott's Hall Maroons Looking to Develop Area as Major Attraction". Jamaica Information Service. Archived from the original on 26 April 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- Staff. "11th Annual International Maroon Conference & Festival Magazine 2019". Charles Town Maroons. Charles Town Maroons. Archived from the original on 23 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- "Historical Meeting Between The Kingdom Of Ashanti And The Accompong Maroons In Jamaica", Modern Ghana, 2 May 2016

- "African DNA Project mtDNA Haplogroup L1b". 8 May 2008. Archived from the original on 8 May 2008.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Jimenez Roman, Miriam. "Africa's Legacy". www.smithsonianeducation.org. Retrieved 21 December 2019.

- Din, Gilbert C. (1999). Spaniards, Planters, and enslaved people: The Spanish Regulation of Slavery in Louisiana, 1763–1803. Texas A&M University Press. ISBN 0890969043.

- Hall, Gwendolyn Midlo (1995). Africans in Colonial Louisiana: The Development of Afro-Creole Culture in the Eighteenth Century. Louisiana State University Press. ISBN 0807119997.

- Kuipers, Ank (30 November 2005). "Villagers return to site of 1986 Suriname massacre". Forest Peoples Programme. Reuters. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "The Ndyuka Treaty Of 1760: A Conversation with Granman Gazon". Cultural Survival (in Dutch). Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Encyclopaedie van Nederlandsch West-Indië - Page 154 - Boschnegers" (PDF). Digital Library for Dutch Literature (in Dutch). 1916. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "The Aluku and the Communes in French Guiana". Cultural Survival. September 1989. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Origins of the Suriname Kwinti Maroons". Brill. 1992. Retrieved 21 July 2020.

- "Parcours La Source". Parc-Amazonien-Guyane (in French). Retrieved 1 June 2020.

- Case of the Saramaka People v. Suriname, Judgment of November 28, 2007, Inter-American Court of Human Rights (La Corte Interamericana de Derechos Humanos), accessed 21 May 2009.

- Boven, Karin M. (2006). Overleven in een grensgebied: Veranderingsprocessen bij de Wayana in Suriname en Frans-Guyana - Page 207 (PDF). Amsterdam: Rozenberg Publishers.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- French, Howard W (14 April 1991). "To Suriname Refugees, Truce Means Betrayal". New York Times. Retrieved 14 June 2018.

- "Live blog: Verkiezing president en vicepresident Suriname". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Inauguratie nieuwe president van Suriname op Onafhankelijkheidsplein". Waterkant (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- "Marronorganisaties blij met Brunswijk als vp-kandidaat". De Ware Tijd (in Dutch). Retrieved 13 July 2020.

- The African Diaspora in the Indian Ocean

Sources

Literature

- History of the Maroons

- Russell Banks (1980), The Book of Jamaica.

- Campbell, Mavis Christine (1988), The Maroons of Jamaica, 1655–1796: a history of resistance, collaboration & betrayal, Granby, Mass.: Bergin & Garvey. ISBN 0-89789-148-1

- Corzo, Gabino La Rosa (2003), Runaway Slave Settlements in Cuba: Resistance and Repression (translated by Mary Todd), Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 0-8078-2803-3

- Dallas, R. C. The History of the Maroons, from Their Origin to the Establishment of Their Chief Tribe at Sierra Leone. 2 vols. London: Longman. 1803.

- De Granada, Germán (1970), Cimarronismo, palenques y Hablas "Criollas" en Hispanoamérica Instituto Caro y Cuero, Santa Fe de Bogotá, Colombia, OCLC 37821053 (in Spanish)

- Diouf, Sylviane A. (2014), Slavery's Exiles: The Story of the American Maroons, New York: NYU Press, ISBN 978-0814724378

- Honychurch, Lennox (1995), The Dominica Story, London: Macmillan. ISBN 0-333-62776-8 (Includes extensive chapters on the Maroons of Dominica)

- Hoogbergen, Wim S. M. Brill (1997), The Boni Maroon Wars in Suriname, Academic Publishers. ISBN 90-04-09303-6

- Learning, Hugo Prosper (1995), Hidden Americans: Maroons of Virginia and the Carolinas Garland Publishing, New York, ISBN 0-8153-1543-0

- Price, Richard (ed.) (1973), Maroon Societies: rebel slave communities in the Americas, Garden City, N.Y.: Anchor Books. ISBN 0-385-06508-6

- Thompson, Alvin O. (2006), Flight to Freedom: African runaways and maroons in the Americas University of West Indies Press, Kingston, Jamaica, ISBN 976-640-180-2

- van Velzen, H.U.E. Thoden and van Wetering, Wilhelmina (2004), In the Shadow of the Oracle: Religion as Politics in a Suriname Maroon Society, Long Grove, Illinois: Waveland Press. ISBN 1-57766-323-3

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Maroons. |

- Chaglar, Alkan. "The World of Surinam". toplumpostasi.net. Archived from the original on September 28, 2007. (The Maroons, Hindustanis and others of Surinam.)

- Lagace, Robert O. "Society-BUSH-NEGROES: Culture summary". Archived from the original on 2014-03-12.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link) A good short history of the "Bush Negroes" of Suriname.

- Mosis, André. "Articles on Suriname Maroons and their culture in Dutch and English". Kingbotho.

- Reidell, Helen Reidell (January–February 1990). "The Maroon Culture of Endurance". Américas. 42. pp. 46–49. Italic or bold markup not allowed in:

|work=(help) (A history of Jamaican Maroons.) - Smithsonian Institution Traveling Exhibition Service (SITES) in collaboration with the Center for Folklife and Cultural Heritage, with the support of the Special Exhibition Fund of the Smithsonian Institution (March 1999). "Creativity and Resistance: Maroon Cultures in the Americas". Smithsonian.

- Various artists. "Music from Aluku: Maroon Sounds of Struggle, Solace, and Survival". Smithsonian Folkways.

- Black Prisoners of War at Porchester Castle