Christian martyr

A martyr is a person who was killed because of their testimony of Jesus and God.[1] In years of the early church, this often occurred through death by sawing, stoning, crucifixion, burning at the stake or other forms of torture and capital punishment. The word "martyr" comes from the Koine word -> μάρτυς, mártys, which means "witness" or "testimony".

At first, the term applied to Apostles. Once Christians started to undergo persecution, the term came to be applied to those who suffered hardships for their faith. Finally, it was restricted to those who had been killed for their faith. The early Christian period before Constantine I was the "Age of martyrs". "Early Christians venerated martyrs as powerful intercessors, and their utterances were treasured as inspired by the Holy Spirit."[2]

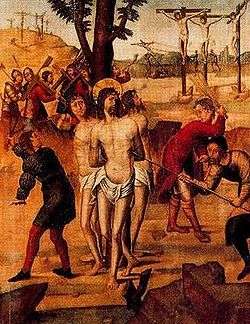

In western Christian art, martyrs are often shown holding a palm frond as an attribute, representing the victory of spirit over flesh, and it was widely believed that a picture of a palm on a tomb meant that a martyr was buried there.[3]

Etymology

The use of the word μάρτυς (mär-tüs) in non-biblical Greek was primarily in a legal context. It was used for a person who speaks from personal observation. The martyr, when used in a non-legal context, may also signify a proclamation that the speaker believes to be truthful. The term was used by Aristotle for observations, but also for ethical judgments and expressions of moral conviction that can not be empirically observed. There are several examples where Plato uses the term to signify "witness to truth", including in Laws.[4]

Background

.jpg)

The Greek word martyr signifies a "witness" who testifies to a fact he has knowledge about from personal observation. It is in this sense that the term first appears in the Book of Acts, in reference to the Apostles as "witnesses" of all that they had observed in the public life of Christ. In Acts 1:22, Peter, in his address to the Apostles and disciples regarding the election of a successor to Judas, employs the term with this meaning: "Wherefore, of these men who have accompanied with us all the time that the Lord Jesus came in and went out among us, beginning from the baptism of John until the day he was taken up from us, one of these must be made witness with us of his resurrection".[5]

The Apostles, from the beginning, faced grave dangers until eventually almost all suffered death for their convictions. Thus, within the lifetime of the Apostles, the term martyrs came to be used in the sense of a witness who at any time might be called upon to deny what he testified to, under penalty of death. From this stage the transition was easy to the ordinary meaning of the term, as used ever since in Christian literature: a martyr, or witness of Christ, is a person who suffers death rather than denies his faith. St. John, at the end of the first century, employs the word with this meaning.[5] A distinction between martyrs and confessors is traceable to the latter part of the second century: those only were martyrs who had suffered the extreme penalty, whereas the title of confessors was given to Christians who had shown their willingness to die for their belief, by bravely enduring imprisonment or torture, but were not put to death. Yet the term martyr was still sometimes applied during the third century to persons still living, as, for instance, by Cyprian who gave the title of martyrs to a number of bishops, priests, and laymen condemned to penal servitude in the mines.[5]

Origins

Religious martyrdom is considered one of the more significant contributions of Second Temple Judaism to western civilization. It is believed that the concept of voluntary death for God developed out of the conflict between King Antiochus Epiphanes IV and the Jewish people. 1 Maccabees and 2 Maccabees recount numerous martyrdoms suffered by Jews resisting the Hellenizing of their Seleucid overlords, being executed for such crimes as observing the Sabbath, circumcising their children or refusing to eat pork or meat sacrificed to foreign gods. With few exceptions, this assumption has lasted from the early Christian period to this day, accepted both by Jews and Christians.

According to Daniel Boyarin, there are "two major theses with regard to the origins of Christian martyrology, which [can be referred to] as the Frend thesis and the Bowersock thesis". Boyarin characterizes W.H.C. Frend's view of martyrdom as having originated in "Judaism" and Christian martyrdom as a continuation of that practice. Frend argues that the Christian concept of martyrdom can only be understood as springing from Jewish roots. Frend characterizes Judaism as "a religion of martyrdom" and that it was this "Jewish psychology of martyrdom" that inspired Christian martyrdom. Frend writes, "In the first two centuries AD. there was a living pagan tradition of self-sacrifice for a cause, a preparedness if necessary to defy an unjust ruler, that existed alongside the developing Christian concept of martyrdom inherited from Judaism."[6]

In contrast to Frend's hypothesis, Boyarin describes G.W. Bowersock's view of Christian martyrology as being completely unrelated to the Jewish practice, being instead "a practice that grew up in an entirely Roman cultural environment and then was borrowed by Jews". Bowersock argues that the Christian tradition of martyrdom came from the urban culture of the Roman Empire, especially in Asia Minor:

Martyrdom was ... solidly anchored in the civic life of the Graeco-Roman world of the Roman empire. It ran its course in the great urban spaces of the agora and the amphitheater, the principal settings for public discourse and for public spectacle. It depended upon the urban rituals of the imperial cult and the interrogation protocols of local and provincial magistrates. The prisons and brothels of the cities gave further opportunities for the display of the martyr’s faith.[7]

Boyarin points out that, despite their apparent opposition to each other, both of these arguments are based on the assumption that Judaism and Christianity were already two separate and distinct religions. He challenges that assumption and argues that "making of martyrdom was at least in part, part and parcel of the process of the making of Judaism and Christianity as distinct entities".[8]

Theology

Tertullian, one of the 2nd century Church Fathers wrote that "the blood of martyrs is the seed of the Church", implying that the martyrs' willing sacrifice of their lives leads to the conversion of others.[9]

The age of martyrs also forced the church to confront theological issues such as the proper response to those Christians who "lapsed" and renounced the Christian faith to save their lives: were they to be allowed back into the Church? Some felt they should not, while others said they could. In the end, it was agreed to allow them in after a period of penance. The re-admittance of the "lapsed" became a defining moment in the Church because it allowed the sacrament of repentance and readmission to the Church despite issues of sin. This issue caused the Donatist and Novatianist schisms.[10][11]

"Martyrdom for the faith ...became a central feature in the Christian experience."[12] "Notions of persecution by the "world," ...run deep in the Christian tradition. For evangelicals who read the New Testament as an inerrant history of the primitive church, the understanding that to be a Christian is to be persecuted is obvious, if not inescapable"[13]

The "eschatological ideology" of martyrdom was based on an irony found in the Pauline epistles: "to live outside of Christ is to die, and to die in Christ is to live."[14][15] In Ad Martyras, Tertullian writes that some Christians "eagerly desired it" (et ultro appetita) martyrdom.[15]

The martyr homilies were written in ancient Greek by authors such as Basil of Caesarea, Gregory of Nyssa, Asterius of Amasea, John Chrysostom and Hesychius of Jerusalem. These homilies were part of the hagiographical tradition of saints and martyrs.[16]

This experience, and the associated martyrs and apologists, would have significant historical and theological consequences for the developing faith.[17]

Among other things, persecution sparked the devotion of the saints, facilitated the rapid growth and spread of Christianity, prompted defenses and explanations of Christianity (the "apologies") and, in its aftermath, raised fundamental questions about the nature of the church.

The Early Church

Saint Stephen was the first martyr in Christian tradition.[18] Judith Perkins has written that many ancient Christians believed that "to be a Christian was to suffer."[19] Jesus Christ died to save the souls of all who believed in him, demonstrating the greatest sacrifice. He was crucified, however, not technically martyred.

The doctrines of Christ's apostles brought the Early Church into conflict with the Sanhedrin. In The Book of Acts, Luke describes how the early Church "began to strain the bounds of early Judaism".[20] Stephen was accused of blasphemy and denounced the Sanhedrin as "stiff-necked" people who, just as their ancestors had done, persecute prophets.[21] D. A. Carson and Douglas J. Moo write that Stephen was stoned to death after he was "falsely accused of speaking against the temple and the law".[20][22]

In many Christian traditions, Saint Antipas is widely believed to be the martyred Antipas written about in Revelation 2:13. John the Apostle is traditionally believed to have ordained Antipas as bishop of Pergamon while Domitian was the Roman emperor. According to tradition, Antipas was martyred in ca. 92 AD by slowly being burned alive in a brazen bull, for casting out demons that were worshiped by the locals.

The Book of Revelation calls Jesus, as well as Antipas, "the faithful witness" (o martys o pistos).[23][24][18]

The lives of the martyrs became a source of inspiration for some Christians, and their relics were honored. Numerous crypts and chapels in the Roman catacombs bear witness to the early veneration for those champions of freedom of conscience. Special commemoration services, at which the holy Sacrifice were offered over their tombs gave rise to the time honoured custom of consecrating altars by enclosing in them the relics of martyrs.[5]

The Roman Empire

In its first three centuries, the Christian church endured periods of persecution at the hands of Roman authorities. Christians were persecuted by local authorities on an intermittent and ad-hoc basis. In addition, there were several periods of empire-wide persecution which were directed from the seat of government in Rome.

Christians were the targets of persecution because they refused to worship the Roman gods or to pay homage to the emperor as divine. In the Roman Empire, refusing to sacrifice to the Emperor or the empire's gods was tantamount to refusing to swear an oath of allegiance to one's country.

The cult of the saints was significant to the process of Christianization, but during the first centuries of the Church the celebrations venerating the saints took place in hiding.[16]:4 Michael Gaddis writes that, "The Christian experience of violence during the pagan persecutions shaped the ideologies and practices that drove further religious conflicts over the course of the fourth and fifth centuries."[25] Martyrdom was a formative experience and influenced how Christians justified or condemned the use of violence in later generations.[25] Thus, the collective memory of religious suffering found in early Christian works on the historical experience of persecution, religious suffering and martyrdom shaped Christian culture and identity.[26]

The Middle Ages

In the 15th century moral treatise Dives and Pauper about the Ten Commandments, the figure Dive poses this question about the First Commandment: "Why are there no martyrs these days, as there used to be?" Pauper responds that The English were creating many new martyrs sparing "neither their own king nor their own bishops, no dignity, no rank, no status, no degree". Pauper's statement is based on historical events, including the murder of King Richard II and the executions of Archbishop Richard Scrope.[27] Dana Piroyansky uses the term "political martyrs" for men of "high estate," including kings and Bishops, who were killed during the Late Middle Ages during the course of the rebellions, civil wars, regime changes and other political upheavals of the 14th and 15th centuries. Piroyansky notes that although these men were never formally canonized as saints they were venerated as miracle-working martyrs and their tombs were turned into shrines following their violent and untimely deaths.[27]:2 J.C. Russell has written that the "cults of political saints" may have been a way of "showing resistance to the king" that would have been difficult to control or punish.[27]:3

Degrees of martyrdom

Some Roman Catholic writers (such as Thomas Cahill) continue to use a system of degrees of martyrdom that was developed in early Christianity.[28] Some of these degrees bestow the title of martyr on those who sacrifice large elements of their lives alongside those who sacrifice life itself. These degrees were mentioned by Pope Gregory I in Homilia in Evangelia, he wrote of "three modes of martyrdom, designated by the colors, red, blue (or green), and white".[29] A believer was bestowed the title of red martyr due to either torture or violent death by religious persecution. The term "white martyrdom" was used by the Church Father Jerome, "for those such as desert hermits who aspired to the condition of martyrdom through strict asceticism".[29] Blue (or green) martyrdom "involves the denial of desires, as through fasting and penitent labors without necessarily implying a journey or complete withdrawal from life".[29]

Also along these lines are the terms "wet martyr" (a person who has shed blood or been executed for the faith) and "dry martyr" which is a person who "had suffered every indignity and cruelty" but not shed blood, nor suffered execution.[30]

Christian martyrs today

The Center for the Study of Global Christianity of Gordon–Conwell Theological Seminary, an evangelical seminary based in Hamilton, Massachusetts, has estimated that 100,000 Christians die annually for their faith. Archbishop Silvano Maria Tomasi, permanent observer of the Holy See to the United Nations later referred to this number in a radio address to the 23rd session of the Human Rights Council.[31][32]

However, the methodology used in arriving at this number has been criticized. The majority of the one million people the Center counted as Christians who died as martyrs between 2000 and 2010, died during the Civil War in the Democratic Republic of Congo. The report did not take into consideration political or ethnic differences. Professor Thomas Schirrmacher from the International Society for Human Rights, considers the figure to be closer to 10,000. Todd Johnson, director of the CSGC, says his centre has abandoned this statistic. Vatican reporter and author of The Global War on Christians John Allen said: "I think it would be good to have reliable figures on this issue, but I don't think it ultimately matters in terms of the point of my book, which is to break through the narrative that tends to dominate discussion in the West – that Christians can't be persecuted because they belong to the world's most powerful church. The truth is two-thirds of the 2.3 billion Christians in the world today live… in dangerous neighbourhoods. They are often poor. They often belong to ethnic, linguistic and cultural minorities. And they are often at risk."[33]

See also

- List of Christian martyrs

- Carthusian Martyrs

- Catacombs of Rome

- Christian pacifism

- Coptic saints

- Drina Martyrs

- Forty Martyrs of England and Wales

- Great Martyr

- Irish Catholic Martyrs

- Korean Martyrs

- Latter Day Saint martyrs

- Marian Persecutions

- Martyrdom in Islam

- Martyrdom in Judaism

- Martyrs Mirror

- Martyrs of Japan

- Martyrs of the Spanish Civil War

- Murders of Jesuits in El Salvador

- New Martyr

- North American Martyrs

- Palm branch

- Palm (Easter)

- Persecution of Christians

- Religious Persecution

- Roman Emperor

- Saints of the Cristero War

- The Oxford Martyrs

- Uganda Martyrs

- Vietnamese Martyrs

- Martyrs of Laos

References

- Freedman, David Noel; Beck, Astrid B; Myers, Allen C (2009). Eerdmans dictionary of the Bible. Grand Rapids; Cambridge: William B. Eerdmans Publishing Company. ISBN 978-0-8028-2400-4.

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). martyr. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Hassett, M. (1911). "Palm in Christian Symbolism". The Catholic Encyclopedia.

- Kittel, Gerhard; Friedrich, Gerhard (2006). Bromiley, Geoffrey William (ed.). Theological dictionary of the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich: Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2243-7.

- "Hassett, Maurice. "Martyr." The Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company, 1910. 12 Dec. 2014". Newadvent.org. 1 October 1910. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Frend, W. H. C. (2000). Esler, Philip (ed.). Martyrdom and Political Oppression. The Early Christian World. 2. p. 818.

- Bowersock, G.W. (1995). Martyrdom and Rome.

- Boyarin, Daniel (1999). Dying for God. Stanford University Press. p. 93. ISBN 978-0-8047-3704-3.

- Salisbury, Joyce Ellen (2004). The Blood of Martyrs: Unintended Consequences of Ancient Violence. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-94129-6.

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). Donatism. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cross, F. L., ed. (2005). Novatianism. The Oxford dictionary of the Christian church. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bryant, Joseph M. (June 1993). "The Sect-Church Dynamic and Christian Expansion in the Roman Empire: Persecution, Penitential Discipline, and Schism in Sociological Perspective". The British Journal of Sociology. Blackwell Publishing on behalf of The London School of Economics and Political Science. 44 (2): 303–339. doi:10.2307/591221. JSTOR 591221.

- Watson, Justin (1999). The Christian Coalition: Dreams of Restoration, Demands for Recognition. ISBN 9780312217822.

- Philemon 1:21–231 Corinthians 9:152 Corinthians 6:9Colossians 2:20

- Heffernan, Thomas J.; James E. Shelton (2006). "Paradisus in carcere: The Vocabulary of Imprisonment and the Theology of Martyrdom in the Passio Sanctarum Perpetuae et Felicitas". Journal of Early Christian Studies. 14 (2): 217–23. doi:10.1353/earl.2006.0035.

- Leemans, Johan (2003). 'Let us die that we may live': Greek homilies on Christian martyrs from Asia Minor, Palestine and Syria, c. AD 350-c. 450 AD. London: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-24042-0. – via Questia (subscription required)

- Latourette, Kenneth Scott (2000). "The tradition of martyrdom has entered deep into the Christian consciousness". A History of Christianity. Prince Press. I: Beginnings to 1500: 81.

- Danker, Frederick W; Arndt, William; Bauer, Walter (2000). A Greek-English lexicon of the New Testament and other early Christian literature. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-03933-6.

- "Philosophy as Training for Death Reading the Ancient Christian Martyr Acts as Spiritual-Exercises (2006)". Archived from the original on 5 January 2010. Retrieved 27 May 2010.

- Carson, D. A; Moo, Douglas J (2009). An introduction to the New Testament. Grand Rapids, Mich.: Zondervan. ISBN 978-0-310-53956-8.

- "Butler, Alban. Volume XII, The Lives of the Saints, Vol. XII, 1866". Bartleby.com. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

- Acts 6:8–8:3

- Revelation 1:5

- Revelation 3:14

- Gaddis, Michael (2005). There is no crime for those who have Christ: Religious Violence in the Christian Roman Empire. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520930902.

- Elizabeth Anne Castelli (2004). Martyrdom and memory: early Christian culture making. ISBN 978-0-231-12986-2.

- Piroyansky, Danna (2008). Martyrs in the making: political martyrdom in late medieval England. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-230-51692-2.

- "Red, White and Green Martyrs?". AmericanCatholic.org. Retrieved 19 March 2011.

- Michael Driscoll; J. Michael Joncas (2011). The Order of Mass Study Edition and Workbook. Chicago, IL: Archdiocese of Chicago Liturgy Training Publications.

- Matthew Bunson; Margaret Bunson; Stephen Bunson; Pope John Paul II (1999). John Paul II's Book of Saints. Huntington, IN: Our Sunday Visitor Publishing Division.

- Johnson, Todd M. "The case for higher numbers of Christian martyrs" (PDF). www.gordonconwell.edu/. Gordon-Conwell Theological Seminary. Archived from the original (PDF) on 7 September 2015. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- Tomasi, Silvano M. (28 May 2013). "Vatican to UN: 100 thousand Christians killed for the faith each year". Vatican Radio. Retrieved 19 April 2015.

- "Are there really 100,000 new Christian martyrs every year?". BBC News. 12 November 2013. Retrieved 28 May 2017.

Sources

- York, Tripp (2007). The Purple Crown: The Politics of Martyrdom. Herald Press. ISBN 978-0-8361-9393-0.

- Whitfield, Joshua J. (2009). Pilgrim Holiness: Martyrdom as Descriptive Witness. Cascade. ISBN 978-1-60608-175-4.

- Rick Wade (27 May 1999). "Persecution in the Early Church". Archived from the original on 9 October 2004. Retrieved 9 October 2004. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Foxe, John. William Byron Forbush (ed.). "Foxe's Book of Martyrs". OCLC 751705715. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Keane, Paul (2009). The Martyr's Crown. Family Publications. ISBN 978-1907380006.

- Talk, D.C. (2014). Jesus Freaks: DC Talk and The Voice of the Martyrs—Stories of Those Who Stood For Jesus. Bethany House Publishers. ISBN 978-0764212024.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Christian martyrs. |

- Holy Women of the Syrian Orient. 25 June 1987. ISBN 9780520920958.

- Butler, Alban (1984). Lives of the Saints.

- Saints and Their Legends : A Selection of Saints from Michael the Archangel to the Fifteenth Century.

- "Martyr". Catholic Encyclopedia. 9. New York: Robert Appleton Company. 1910. Retrieved 5 May 2018.