Aylesbury duck

The Aylesbury duck is a breed of domesticated duck, bred mainly for its meat and appearance. It is a large duck with pure white plumage, a pink bill, orange legs and feet, an unusually large keel, and a horizontal stance with its body parallel to the ground. The precise origins of the breed are unclear, but raising white ducks became popular in Aylesbury, Buckinghamshire, England, in the 18th century owing to the demand for white feathers as a filler for quilts. Over the 19th century selective breeding for size, shape and colour led to the Aylesbury duck.

Duck rearing became a major industry in Aylesbury in the 19th century. The ducks were bred on farms in the surrounding countryside. Fertilised eggs were brought into the town's "Duck End", where local residents would rear the ducklings in their homes. The opening of a railway to Aylesbury in 1839 enabled cheap and quick transport to the markets of London, and duck rearing became highly profitable. By the 1860s the duck rearing industry began to move out of Aylesbury into the surrounding towns and villages, and the industry in Aylesbury itself began to decline.

In 1873 the Pekin duck was introduced to the United Kingdom. Although its meat was thought to have a poorer flavour than that of the Aylesbury duck, the Pekin was hardier and cheaper to raise. Many breeders switched to the Pekin duck or to Aylesbury-Pekin crosses. By the beginning of the 20th century competition from the Pekin duck, inbreeding, and disease in the pure-bred Aylesbury strain and the rising cost of duck food meant the Aylesbury duck industry was in decline.

The First World War badly damaged the remaining duck industry in Buckinghamshire, wiping out the small scale producers and leaving only a few large farms. Disruption caused by the Second World War further damaged the industry. By the 1950s only one significant flock of Aylesbury ducks remained in Buckinghamshire, and by 1966 there were no duck-breeding or -rearing businesses of any size remaining in Aylesbury itself. Although there is only one surviving flock of pure Aylesbury ducks in the United Kingdom and the breed is critically endangered in the United States, the Aylesbury duck remains a symbol of the town of Aylesbury, and appears on the coat of arms of Aylesbury and on the club badge of Aylesbury United.

Origins and description

.jpg)

The precise origin of the Aylesbury duck is unclear.[1] Before the 18th century, duck breeds were rarely recorded in England, and the common duck, bred for farming, was a domesticated form of the wild mallard. The common duck varied in colour, and as in the wild, white ducks would occasionally occur.[1] White ducks were particularly prized, as their feathers were popular as a filler for quilts.[2]

In the 18th century selective breeding of white common ducks led to a white domestic duck, generally known as the English White.[1] Since at least the 1690s ducks had been farmed in Aylesbury,[3] and raising English Whites became popular in Aylesbury and the surrounding villages.[4] By 1813 it was remarked that "ducks form a material article at market from Aylesbury and places adjacent: they are white, and as it seems of an early breed: they are bred and brought up by poor people, and sent to London by the weekly carriers".[5] The duck farmers of Aylesbury went to great lengths to ensure the ducks retained their white colouring, keeping them clear of dirty water, soil with a high iron content and bright sunlight, all of which could discolour the ducks' feathers.[6] Over time, selective breeding of the English White for size and colour gradually led to the development of the Aylesbury duck.[6]

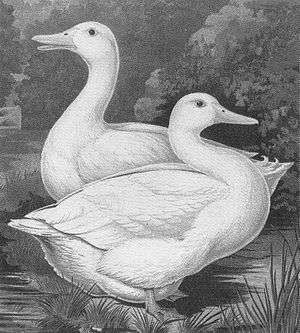

A rather large duck breed,[7] the Aylesbury duck has pure white plumage and bright orange legs and feet.[1] Its legs are placed midway along the body and it stands with its underside parallel to the ground, giving it a body described as "boat-shaped".[1][8] It has a relatively long and thin swan-like neck, and a long pink bill which comes straight out from the head.[1][note 1]

An Aylesbury duckling incubates in the egg for 28 days.[9] Until eight weeks after hatching, the time of their first moult, ducks and drakes (females and males) are almost indistinguishable. After moulting, males have two or three curved tail feathers and a fainter, huskier quack than the female. By one year of age, females and males grow to an average weight of 6 and 7 pounds (2.7 and 3.2 kg) respectively, although males can reach around 10 pounds (4.5 kg).[1][7]

Unlike the Rouen duck, the other popular meat variety in England in the 19th century, Aylesbury ducks lay eggs from early November.[6] Aylesbury ducks fatten quickly and by eight weeks after hatching weigh up to 5 pounds (2.3 kg), large enough to eat but still young and extremely tender.[10] Consequently, their meat came onto the market from February onwards, after the close of the game season but before the earliest spring chickens were on sale.[6] Rouen ducks, whose mallard-like coloration made them less valuable, lay eggs from early February and take six months to grow large enough to eat.[6] As a consequence, Aylesbury ducks were sold primarily in the spring and summer, and Rouen ducks in the autumn and winter.[6][note 2]

Aylesbury duck farming

The white Aylesbury duck is, and deservedly, a universal favourite. Its snowy plumage and comfortable comportment make it a credit to the poultry-yard, while its broad and deep breast, and its ample back, convey the assurance that your satisfaction will not cease at its death. In parts of Buckinghamshire, this member of the duck family is bred on an extensive scale; not on plains and commons, however, as might be naturally imagined, but in the abodes of the cottagers. Round the walls of the living-rooms, and of the bedroom even, are fixed rows of wooden boxes, lined with hay; and it is the business of the wife and children to nurse and comfort the feathered lodgers, to feed the little ducklings, and to take the old ones out for an airing. Sometimes the "stock" ducks are the cottager's own property, but it more frequently happens that they are intrusted to his care by a wholesale breeder, who pays him so much per score for all ducklings properly raised. To be perfect, the Aylesbury duck should be plump, pure white, with yellow feet, and a flesh coloured beak.[11]

Unlike most livestock farming in England at this time, the duck breeders and duck rearers of Aylesbury formed two separate groups.[12] Stock ducks—i.e., ducks kept for breeding—were kept on farms in the countryside of the Aylesbury Vale, away from the polluted air and water of the town. This kept the ducks healthy, and meant a higher number of fertile eggs.[10]

Stock ducks would be chosen from ducklings hatched in March, with a typical breeder keeping six males and twenty laying females at any given time.[13] The females would be kept for around a year before mating, typically to an older male. They would then generally be replaced, to reduce the problems of inbreeding.[14] Stock ducks were allowed to roam freely during the day, and would swim in local ponds which, although privately owned, were treated as common property among the duck breeders;[13] breeders would label their ducks with markings on the neck or head.[14] The stock ducks would forage for greenery and insects, supplemented by greaves (the residue left after the rendering of animal fat).[14] As ducks lay their eggs at night, the ducks would be brought indoors overnight.[14]

Female Aylesbury ducks would not sit still for the 28 days necessary for their eggs to hatch, and as a consequence the breeders would not allow mothers to sit on their own eggs. Instead the fertilised eggs would be collected and transferred to the "duckers" of Aylesbury's Duck End.[15][note 3]

Rearing

The duckers of Aylesbury would buy eggs from the breeders,[10] or be paid by a breeder to raise the ducks on their behalf,[11] and would raise the ducklings in their homes between November and August as a secondary source of income. Duckers were typically skilled labourers, who invested surplus income in ducklings. Many of the tasks related to rearing the ducks would be carried out by the women of the household,[10] particularly the care of newly hatched ducklings.[9]

The eggs would be divided into batches of 13, and placed under broody chickens.[9][note 4] In the last week of the four-week incubation period the eggs would be sprinkled daily with warm water to soften the shells and allow the ducklings to hatch.[9]

Newly hatched Aylesbury ducklings are timid and thrive best in small groups, so the duckers would divide them into groups of three or four ducklings, each accompanied by a hen. As the ducklings grew older and gained confidence, they would be kept in groups of around 30.[9] Originally the ducks would be kept in every room in the ducker's cottage, but towards the end of the 19th century they were kept in outdoor pens and sheds with suitable protection against cold weather.[9]

The aim of the ducker was to get every duckling as fat as possible by the age of eight weeks (the first moult, the age at which they would be killed for meat), while avoiding any foods which would build up their bones or make their flesh greasy.[17] In their first week after hatching, the ducklings would be fed on boiled eggs, toast soaked in water, boiled rice and beef liver. From the second week on, this diet would gradually be replaced by barley meal and boiled rice mixed with greaves. (Some larger-scale duckers would boil a horse or sheep and feed this to the ducklings in place of greaves.)[17] This high-protein diet was supplemented with nettles, cabbage and lettuce to provide a source of vitamins.[17][note 5] As with all poultry, ducks require grit in their diet to break up the food and make it digestible. Aylesbury ducklings' drinking water was laced with grit from Long Marston and Gubblecote;[17] this grit also gave their bills their distinctive pinkish colour.[7] Around 85% of ducklings would survive this eight-week rearing process to be sent to market.[9]

Walter Rose describing ducks in Haddenham, circa 1925

While ducks are naturally aquatic, swimming can be dangerous to young ducklings, and it can also restrict a duck's growth. Thus, although duckers would ensure the ducklings always had a trough or sink to paddle in, the ducklings would be kept away from bodies of water while they were growing. The exception was shortly before slaughter, when the ducklings would be taken for one swim in a pond, as it helped them to feather properly.[18]

Although there were a few large-scale duck rearing operations in Aylesbury, raising thousands of ducklings each season, the majority of Aylesbury's duckers would raise between 400 and 1,000 ducklings each year.[10] Because ducking was a secondary occupation, it was not listed in Aylesbury's census returns or directories and it is impossible to know how many people were engaged in it at any given time.[10] Kelly's Directory for 1864 does not list a single duck farmer in Aylesbury,[10] but an 1885 book comments that:

In the early years of the present [19th] century almost every householder at the "Duck End" of the town followed the avocation of ducker. In a living room it was no uncommon sight to meet with young ducks of different ages, divided in pens and monopolizing the greatest space of the apartment, whilst expected new arrivals often were carefully lodged in the bedchamber.[19]

The Rev. Richard Parkinson St. John Priest, Secretary to the Norfolk Agricultural Society, reporting on Aylesbury to the Board of Agriculture and Internal Improvement, 1813

The Duck End was one of the poorer districts of Aylesbury. Until the end of the 19th century it had no sewers or refuse collections.[16] The area had a number of open ditches filled with stagnant water, and outbreaks of malaria and cholera were common.[4] The cottages had inadequate ventilation and lighting,[16] and no running water.[14] Faeces from the duck ponds permeated the local soil and seeped into the cottages through cracks in the floors.[16]

Slaughter and sale

When the ducklings were ready for slaughter, the duckers would generally kill them on their own premises. The slaughter would generally take place in the morning, to ensure the ducks would be ready for market in the evening. To keep the meat as white as possible, the ducks would be suspended upside down and their necks broken backwards, and held in this position until their blood had run towards their heads. They were kept in this position for ten minutes before being plucked, as otherwise their blood would collect in those parts of the body from which the feathers had been plucked.[18] The plucking was generally carried out by the women of the household.[18] The plucked carcasses would be sent to market, and the feathers would be sold direct to London dealers.[20]

The market for duck meat in Aylesbury itself was small, and the ducks were generally sent to London for sale. By the 1750s Richard Pococke recorded that four cartloads of ducks were sent from Aylesbury to London every Saturday,[21] and in the late 18th and early 19th centuries the ducks continued to be sent over the Chiltern Hills to London by packhorse or cart.[20]

On 15 June 1839 the entrepreneur and former Member of Parliament for Buckingham, Sir Harry Verney, 2nd Baronet, opened the Aylesbury Railway.[22] Built under the direction of Robert Stephenson,[23] it connected the London and Birmingham Railway's Cheddington railway station on the West Coast Main Line to Aylesbury High Street railway station in eastern Aylesbury.[24] On 1 October 1863 the Wycombe Railway also built a line to Aylesbury, from Princes Risborough railway station to a station on the western side of Aylesbury (the present-day Aylesbury railway station).[24] The arrival of the railway had a powerful impact on the duck industry, and up to a ton of ducks in a night were being shipped from Aylesbury to Smithfield Market in London by 1850.[20]

A routine became established in which salesmen would provide the duckers with labels. The duckers would mark their ducklings with the labels of the firm to whom they wished them to be sold in London. The railway companies would collect ducklings, take them to the stations, ship them to London and deliver them to the designated firms, in return for a flat fee per bird. By avoiding the need for the duckers to travel to market, or the London salesmen to collect the ducklings, this arrangement benefited all concerned, and ducking became very profitable.[20] By 1870 the duck industry was bringing over £20,000 per year into Aylesbury; a typical ducker would make a profit of around £80–£200 per year.[25][note 6]

Developments in the late 19th century

In 1845, the first National Poultry Show was held, at the Zoological Gardens in London; one of the classes of poultry exhibited was "Aylesbury or other white variety". The personal interest of Queen Victoria in poultry farming, and its inclusion in the Great Exhibition of 1851, further raised public interest in poultry. From 1853 the Royal Agricultural Society and the Bath and West of England Society, the two most prominent agricultural societies in England, included poultry sections in their annual agricultural shows. This in turn caused smaller local poultry shows to develop across the country.[28]

Breeders would choose potential exhibition ducks from among newly hatched ducklings in March and April, and they would be given a great deal of extra attention. They would be fed a carefully controlled diet to get them to the maximum weight, and would be allowed out for a few hours each day to keep them in as good a physical condition as possible. Before the show, their legs and feet would be washed, their bills trimmed with a knife and sandpapered smooth, and their feathers brushed with linseed oil.[28] While most breeders would give the ducks a healthy meal before the show to calm them, some breeders would force-feed the ducks with sausage or worms, to get them to as heavy a weight as possible.[29] Exhibition standards judged an Aylesbury duck primarily on size, shape and colour. This encouraged the breeding of larger ducks, with pronounced exaggerated keels, and loose baggy skin.[29] By the beginning of the 20th century the Aylesbury duck had diverged into two separate strains, one bred for appearance and one for meat.[29]

Pekin ducks

In 1873 the Pekin duck was introduced from China to Britain for the first time. Superficially similar in appearance to an Aylesbury duck, a Pekin is white with orange legs and bill, with its legs near the rear, giving it an upright stance while on land.[8] Although not thought to have such a delicate flavour as the Aylesbury,[30] the Pekin was hardier, a more prolific layer,[8] fattened more quickly,[31] and was roughly the same size as an Aylesbury at nine weeks.[8]

Aylesbury ducks, meanwhile, were becoming inbred, meaning fertile eggs were scarcer and the ducks were more susceptible to disease.[30][32] Exhibition standards had led to selection for an exaggerated keel by breeders, despite it being unpopular with dealers and consumers.[8] Poultry show judges also admired the long neck and upright posture of Pekin ducks over the boat-like stance of the Aylesbury.[8] Some of the breeders in the Aylesbury area began to cross Pekin ducks with the pure Aylesbury strain. Although the Aylesbury-Pekin cross ducks did not have the delicate flavour of the pure Aylesbury, they were hardier and much cheaper to raise.[8]

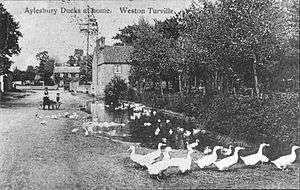

Until the mid-19th century duck rearing was concentrated on the Duck End, but by the 1860s it had spread to many other towns and villages in the area, particularly Weston Turville and Haddenham.[33] Contamination of Aylesbury's soil by years of duck rearing, and new public health legislation which ended many traditional practices, caused the decline of the duck rearing industry in the Duck End, and by the 1890s the majority of Aylesbury ducks were raised in the villages rather than the town itself.[33] Population shifts and the improved national rail network reduced the need to rear ducks near London, and large duck farms opened in Lancashire, Norfolk and Lincolnshire.[33] Although the number of ducks raised nationwide continued to grow, between 1890 and 1900 the number of ducks raised in the Aylesbury area remained static, and from 1900 it began to drop.[33]

Decline

By the time Beatrix Potter's 1908 The Tale of Jemima Puddle-Duck—about an Aylesbury duck although set in Cumbria—caused renewed interest in the breed, the Aylesbury duck was in steep decline.[7] The duckers of Buckinghamshire had generally failed to introduce technological improvements such as the incubator, and inbreeding had dangerously weakened the breed.[30][32] Meanwhile, the cost of duck food had risen fourfold over the 19th century, and from 1873 onwards competition from Pekin and Pekin cross ducks was undercutting Aylesbury ducks at the marketplace.[8]

The First World War devastated the remaining duckers of Buckinghamshire. The price of duck food rose steeply while the demand for luxury foodstuffs fell,[30] and wartime restructuring ended the beneficial financial arrangements with the railway companies.[34] By the end of the war small-scale duck rearing in the Aylesbury Vale had vanished, with duck raising dominated by a few large duck farms.[35] Shortages of duck food in the Second World War caused further disruption to the industry, and almost all duck farming in the Aylesbury Vale ended.[35] A 1950 "Aylesbury Duckling Day" campaign to boost the reputation of the Aylesbury duck had little effect;[36] by the end of the 1950s the last significant farms had closed, other than a single flock in Chesham owned by Mr L. T. Waller,[35] and by 1966 there were no duck breeders or rearers of any size remaining in Aylesbury.[37] As of 2015 the Waller family's farm in Chesham remains in business, the last surviving flock of pure Aylesbury meat ducks in the country.[35][38][39]

Aylesbury ducks were imported into the United States in 1840, although they never became a popular breed. They were, however, added to the American Poultry Association's Standard of Perfection breeding guidelines in 1876.[40] As of 2013, the breed was listed as critically endangered in the United States by The Livestock Conservancy.[41]

Legacy

The Aylesbury duck remains a symbol of the town of Aylesbury. Aylesbury United F.C. are nicknamed "The Ducks" and include an Aylesbury duck on their club badge,[42] and the town's coat of arms includes an Aylesbury duck and plaited straw, representing the two historic industries of the town.[43] The Aylesbury Brewery Company, now defunct, featured the Aylesbury duck as its logo, an example of which can still be seen at the Britannia pub.[44] Duck Farm Court is a shopping area of modern Aylesbury located near the historic hamlet of California, close to one of the main breeding grounds for ducks in the town,[45] and there have been two pubs in the town with the name "The Duck" in recent years; one in Bedgrove that has since been demolished[46] and one in Jackson Road that has recently been renamed.[47]

See also

Notes and references

Notes

- One source describes the bill colour as "like a lady's fingernail".[1]

- The division between Aylesbury ducks in the first half of the year and Rouen ducks in the second was not absolute; Aylesbury ducks were also reared for the Christmas market.[6]

- The "Duck End" was the area bounded by the present-day Castle Street, Whitehall Street and Friarage Road.[16]

- At the start of the laying season an average of eight eggs out of every 13 would hatch, with the proportion hatching successfully increasing over the laying season. The unhatched eggs would be fed to the newly hatched ducklings.[9]

- Aylesbury ducklings are sensitive to Vitamin E deficiency, which causes them to lose their sense of balance, fall over and die.[7]

- In terms of consumer spending power, the £20,000 profit for the Aylesbury duckers is equivalent to around about £1.9 million per year in 2020 terms, while the £80–£200 profit for a typical ducker equates to between £7,700 and £19,000 in 2020 terms.[26] The economy of rural Buckinghamshire in the 19th century included significant elements of tenant farming and payment in kind; the average weekly wage of a rural labourer was only 14s 8d (£71 in terms of 2020 purchasing power).[26][27] Modern price equivalents should only be taken as very rough comparisons.

References

- Ambrose 1982, p. 6.

- Ambrose 1982, pp. 6–8.

- Hanley 1993, p. 48.

- De Rijke 2008, p. 79.

- St. John Priest 1813, p. 331.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 8.

- De Rijke 2008, p. 80.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 32.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 16.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 10.

- Beeton 1861, p. 452.

- "The Duck-Fattening Industry". News. The Times (34233). London. 9 April 1894. col B, p. 12. (subscription required)

- Gibbs 1885, p. 623.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 14.

- Ambrose 1982, pp. 14–16.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 13.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 18.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 19.

- Gibbs 1885, p. 622.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 23.

- Pococke 1888, p. 164.

- Jones 1974, p. 3.

- Lee 1935, p. 235.

- Melton 1984, p. 5.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 24.

- UK Retail Price Index inflation figures are based on data from Clark, Gregory (2017). "The Annual RPI and Average Earnings for Britain, 1209 to Present (New Series)". MeasuringWorth. Retrieved 2 February 2020.

- Ambrose 1982, pp. 24–26.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 26.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 28.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 33.

- "Duck-Breeding Enterprise". Crops And Live Stock. The Times (39213). London. 7 March 1910. col E, p. 4. (subscription required)

- De Rijke 2008, p. 81.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 30.

- Ambrose 1982, pp. 33–34.

- Ambrose 1982, p. 34.

- "Duckling Day at Aylesbury". News. The Times (51730). London. 29 June 1950. col B, p. 3. (subscription required)

- "What's in a name on British dishes". News. The Times (56824). London. 28 December 1966. col E, p. 9. (subscription required)

- Prince, Rose (16 March 2010). "Aylesbury ducks really deliver". Daily Telegraph. London.

- "Richard Waller Breeder of Authentic Aylesbury Ducks: About Us". Richard Waller. Retrieved 11 October 2015.

- Dohner 2001, p. 461.

- "Conservation Priority List", livestockconservancy.org, The Livestock Conservancy, retrieved 3 September 2013

- "The History of Aylesbury United". Aylesbury: Aylesbury United F. C. Archived from the original on 25 October 2010. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- Tomlinson, H. L. (1946). "Aylesbury Town Council Coat of Arms". Aylesbury: Aylesbury Town Council. Archived from the original on 17 July 2011. Retrieved 26 October 2010.

- "Buckinghamshire: Defunct Brewery Livery". The Brewery History Society. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- "Welcome to Duck Farm Court". Aylesbury: Duck Farm Court. 2007. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- "The Duck Latest". Aylesbury: Bedgrove Liberal Democrats. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

- "Licensing of Public Entertainment at the Aylesbury Duck Public House, Jackson Road, Aylesbury". Aylesbury: Aylesbury Vale District Council. Archived from the original on 7 August 2011. Retrieved 28 October 2010.

Bibliography

- Ambrose, Alison (1982). The Aylesbury Duck (1991 ed.). Aylesbury: Buckinghamshire County Museum. ISBN 0-86059-532-3.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Beeton, Isabella (1861). Beeton's Book of Household Management. London: S. O. Beeton Publishing.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- De Rijke, Victoria (2008). Duck. London: Reaktion Books. ISBN 1-86189-350-7.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Dohner, Janet Vorwald (2001). "Ducks: Breed Profiles". In Dohner, Janet Vorwald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Historic and Endangered Livestock and Poultry Breeds. Topeka, Kansas: Yale University Press. p. 461. ISBN 978-0-300-08880-9.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Gibbs, Robert (1885). Buckinghamshire: A History of Aylesbury with its Borough and Hundreds, the Hamlet of Walton, and the Electoral Division. Aylesbury: Robert Gibbs.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hanley, Hugh (1993). Aylesbury: A pictorial history. Chichester: Phillimore. ISBN 0-85033-873-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jones, Ken (1974). The Wotton Tramway (Brill Branch). Locomotion Papers. Blandford: The Oakwood Press. ISBN 0-85361-149-1.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lee, Charles E. (1935). "The Duke of Buckingham's Railways: with special reference to the Brill line". Railway Magazine. 77 (460): 235–241.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Melton, Ian (1984). R. J., Greenaway (ed.). "From Quainton to Brill: A history of the Wotton Tramway". Underground. Hemel Hempstead: The London Underground Railway Society (13). ISSN 0306-8609.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pococke, Richard (1888). The Travels Through England of Dr. Richard Pococke, Successively Bishop of Meath and of Ossory, During 1750, 1751, and Later Years. Works of the Camden Society. London: Camden Society.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- St. John Priest, Richard Parkinson (1813). General View of the Agriculture of Buckinghamshire. London: Sherwood, Neely and Jones.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Aylesbury duck. |